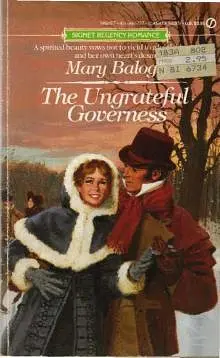

by Mary Balogh

"Yes, I am quite sure," Jessica assured him. "Now do tell me, sir, how do you see the national character of the Russians?"

They both laughed.

But through her laughter Jessica became aware of a prickling sensation down her spine. She knew even before she turned her head rather jerkily in the direction of the door that Lord Rutherford was there. He was standing rather indolently in the doorway, looking quite splendid, she thought, in dark blue velvet coat, silver silk knee breeches, and white linen and lace. His narrowed eyes were directed at her. She turned her head abruptly back to her companion and immediately regretted the rather gauche action. But it was too late to turn back and incline her head or smile easily.

"How would you like a description of some of the more spectacular sights of Greece?" Sir Godfrey was asking with a grin. "And incidentally, have you seen the Elgin marbles? They are well worth a visit, though I do believe lady visitors are somewhat frowned upon. It is felt that so much naked stone might have a corrupting influence on them. You would need to be well armed with vinaigrette and eau de cologne and handkerchiefs and whatever else you ladies need to ward off the vapors."

"Never!" Jessica said. "I would not be so poor-spirited, sir. All I would need is a stout gentlemanly arm on which to lean. But yes, all the famous sights, please."

They smiled at each other, and Jessica rested an elbow on her knee and her chin in her hand and prepared to focus all her attention on her companion.

"Godfrey. Miss Moore." Lord Rutherford's voice sounded somewhat bored. He bowed stiffly from the waist. "I hope I am not interrupting a private tete-a-tete?

"To tell the truth, you are, Charles," Sir Godfrey said with a grin as Jessica shook her head in some embarrassment. "I was about to mesmerize Miss Moore with an account of my travels in Greece, and you have come along to spoil all. Since you have heard it all at least twice before, I am bound to have you yawning behind your hand in no more than two minutes."

"When have I ever displayed such bad manners?" his friend asked, drawing up a chair and seating himself. "I shall be merely envious that I do not have a similar topic with which to entice Miss Moore's admiration."

She blushed. He was looking at her quite intently and with a quite unreadable expression on his face. "Have you not made the Grand Tour, my lord?" she asked.

"Alas, no," he said. "The Continent has rarely been free of war since I left off leading strings. My travels have all been confined to these shores, ma'am."

Jessica turned her attention back to Sir Godfrey, who had apparently decided to talk about the less serious aspects of his travels. He kept her amused for the next half hour with comical details about the difficulties of travel and accommodations and language in the part of the world to which his tour had taken him. Other guests who joined their group added to the anecdotes. She found herself almost unaware of the silent presence of Lord Rutherford at her side.

Almost. But not quite, of course. In fact, not at all, she was forced to admit to herself at last. Much as she was growing to like Sir Godfrey Hall, amusing as his stories and those of other members of the group were, there was always Lord Rutherford. She found herself eventually wanting to leap to her feet and turn and run for air. It was hard to shake the memory of the afternoon before, the memory that had kept her awake through much of the night.

She still turned alternately hot and cold at the realization that she must have voluntarily placed her hand in his when her attention was so engrossed by the trapeze artists. And if there was some doubt about that, there was certainly none about the fact that she had hidden her face against his sleeve when she was so afraid that one of the leaping figures would fall to his death from the trapeze.

She had turned to Lord Rutherford for comfort, like a small child. He had not repulsed her-indeed, his free hand had been covering the one she clasped when she had looked to see what she was doing. How he must have been laughing at her, though. How naive and childish he must think her. Or how conniving. Would he think that she was trying to attract him? But why would he think so? He had already offered her carte blanche on two separate occasions.

And now he sat next to her, their arms almost touching, this man who had wished to be her protector, her lover. And the man whose presence could instantly interfere with her heartbeat, her power to think.

"Are you tired of sitting in the same place for so long, Miss Moore?" he was asking her now. "Would you like me to accompany you to the music room?"

"Thank you," she said, looking at him for the first time in half an hour, though they had sat so close during all that time. "That would be pleasant." But she had spoken before her mind had had time to function, she realized even as she got to her feet and laid a hand on Lord Rutherford's sleeve. The muscles of his arm were firm beneath her hand. It was the arm that had held her close on more than one occasion. She felt as if she were suffocating.

"Faith and Aubrey always make an effort to seek out the best musical talent," he was saying conversationally. "I am sure that this trio is worth listening to."

"Yes," she said. "I was hoping not to miss it altogether."

They stood in the doorway to the music room for a few moments while Lord Rutherford located two vacant chairs at quite the other side of the room. He guided her quietly toward them, and they sat side by side until the music came to an end fifteen minutes later. For the first time Jessica did not feel oppressed by his nearness. She sensed that he was quite engrossed by the music.

"Do you play an instrument, my lord?" she asked when the polite applause had died down and while one of the guests took the place of the pianist on the stool.

"The violin," he said shortly. "And you, Jess? I imagine that such an accomplished governess must have all sorts of hidden talents."

Jessica's jaw tightened. "I play the pianoforte," she said.

"And might I ask how the daughter of an impoverished country parson-your own words, Jess- can have had the opportunity to practice on such an instrument?" he asked.

"We had a harpsichord," she said, turning to look fixedly at the young lady who was about to play on the pianoforte. "My mother brought it on her marriage."

"Ah," he said with a half-smile, "the royal princess."

"My lord?" Jessica frowned up at him, but he merely shook his head and looked away from her.

"Perhaps I can prevail upon you to play for the company when Miss Lacey has finished," he said.

Jessica looked up at him in alarm. "Oh, no, my lord," she said. "I am out of practice, and I do not pretend to any extraordinary talent even when I am not."

He turned his head and looked very deliberately into her eyes. "I would have expected you to jump at the opportunity to place yourself even more firmly in the public eye," he said. "You seem to be doing quite famously so far."

Jessica would not look away. "Have you brought me here to quarrel with me, my lord?" she asked. She was whispering, for the pianist had begun her recital. "If so, I must beg to be excused and return to the drawing room."

"To Godfrey?" he whispered back. "Save your smiles and your wiles, if you know what is good for you, Jess. He will not marry you, you know."

"Will he not?" she hissed. "Am I to expect another offer to become a mistress, then?"

He smiled, if such a sneering expression could be called a smile. "It is hardly likely," he said. "I believe he is perfectly comfortable with the female who has held that position for the past two years and more."

"In that case," Jessica said, leaning toward him so that her face was only inches away from his own, "I would say he is due for a change, would not you, my lord? I count my chances quite favorable."

She had the satisfaction of seeing his eyes spark with fury before his expression was suddenly transformed to blandness. He smiled and inclined his head toward a turbaned matron one row ahead of them who had turned and directed an indignant lorgnette their way.

Jessica sat silent and stiffbacked through the lengthy recital that followed. She could not have s

aid afterward whether the performance was worthy of such an occasion or not. She was too preoccupied with feeling the presence of the infuriating man at her side. If she could have risen and escaped without attracting the attention of everyone in the room her way, she would have done so. As it was, she was trapped on the opposite side of the room from the door, and there she must stay.

9

"If You will excuse me, my lord." The pianoforte recital had finally ended, and Lady Bradley had announced that supper was being served. Jessica rose firmly to her feet.

"Are you hungry?" Lord Rutherford asked. "Then I shall escort you. But do not think to escape so easily, Jess. I wish to talk to you."

"Why?" she asked. She turned to smile at other guests who were trying to pass her, and moved closer to her chair. "I really do not believe we have anything to say to each other, my lord. If you wish to appeal to me once again to leave your grandmother's house and seek employment, the answer is no. I intend to accept her hospitality until-well, until other arrangements to my liking can be made. And if you wish to renew your request that I become your mistress, the answer is still no."

"Sit down," he said, and Jessica complied without thinking. The guests around them were slowly leaving the room, presumably in search of supper.

"I want to know who you are," he said. "Whether we like it or not, Jess, you and I seem fated to be thrown into company together, and the situation can only get worse over Christmas. Let me know with whom I deal. Tell me more about yourself."

"What do you wish to know, my lord?" Jessica the presence of the infuriating man at her side. If she could have risen and escaped without attracting the attention of everyone in the room her way, she would have done so. As it was, she was trapped on the opposite side of the room from the door, and there she must stay.

mother, by the way, was a scullery maid at the home of the local squire. My father did not deal in social snobbery."

"And you have inherited your tongue from her," he said, something that was almost a smile curling his lips for a moment. "The harpsichord was a wedding gift from a grateful employer, I suppose?"

Jessica inclined her head and was surprised to see a grin on his face when she looked up again.

"Three minutes," he said. "Your hand was in mine for all of three minutes, Jess. It quite distracted my attention from the trapeze artists, you know."

She blushed but would not break eye contact with him.

"Would the same thing have happened if you had been sitting beside Godfrey?" he asked.

"I have no way of knowing, my lord," Jessica said, very much on her dignity. "The action was quite involuntary."

He laughed and picked up her hand, which was lying in her lap. He turned it over and ran a finger over the lines in her palm. "I wonder what your plan is," he said. "Marriage to a rich and titled gentleman, Jess? One who will treat you as a lady?"

"Yes," she said, watching the long, slim finger on her palm, feeling her whole arm sizzle to life from the tickling sensation of its movements. "Though I could live without the wealth and the title."

"Could you?" he asked, his eyes narrowing as he lifted them to look into hers. "What an enigma you are, Jess. I never know quite when you are lying and when telling the truth. You are becoming something of an obsession with me. Did you know that?"

"No," she whispered.

"And do you care?" he asked. "And will you admit to sharing that obsession?"

"No." She looked away from him.

"I think you do, Jess," he said, his free hand taking her chin and turning her face back to his. "You are neither a gray governess nor a demure young maiden, my dear. You are a woman of unusual passions. You know that you and I are destined to end up together, don't you?"

"In bed?" she asked. "I think not, my lord. You are incapable of ravishing a woman, a fact of which I have had happy proof. Yet there is no other way that you will gain what you want of me."

"You think you will not one day come to me and offer yourself to me?" he asked. His eyes were on her lips.

"Not until hell turns to ice," she said. "One's desires are not the most important forces of life, my lord, not when they are divorced from all more tender feelings."

"Love," he said with a scornful little laugh. "Never tell me you believe in love, Jess? You a romantic? I would not have thought it. I see you as a very practical young lady, an opportunist, no less."

"Let me go, my lord," she said. "Everyone must be served with supper already." She was suffocatingly aware of the hand that still held hers, the other hand beneath her chin, his face only inches from her own. She was fighting the humiliating urge to lean forward and close the gap between their mouths.

He did it for her. "You see?" he said, his lips already touching hers. "You talk of love in one breath and food in the next. Bodily appetites, Jess. They figure very large in your thinking."

And his mouth opened over hers, his tongue tracing a tantalizingly light course around her lips so that sensation vibrated through her.

"Children, children! The proprieties, please!" The dowager duchess's voice was booming enough to set the pair into jolting apart. Yet it was a brightly cheerful voice. Rutherford's eyes sought Jessica's for one moment, and he raised the hand that he still held to his lips before turning to greet his grandmother and mother.

"Miss Moore and I have been discussing our various musical talents," he said, rising lazily to his feet. "Are we too late for supper? I believe Faith can consider the evening a resounding success, Mama."

"I told you they would be in here tete-a-tete, Marianne," the dowager said. "Your mama was becoming convinced that you had left altogether, Charles. But I assured her that if we could just find Jessica, you would not be far away." She tapped him on the sleeve with her fan.

"I am so pleased you could come, Miss Moore," the Duchess of Middleburgh said. "You do look lovely in that particular shade of pink, my dear. Of course, someone with your figure would look delightful even in a sack, I daresay. I have always had to fight against fat, alas. Come along to the supper room while there is still food left. Charles is always indifferent to food and sometimes forgets that his companions are not necessarily so."

"Exactly what I was discovering, Mama," Rutherford said with a bow. "You go along. I want to have a look at this violin while the artist is still at supper. It has quite a superior tone."

"Jeremy." Lord Rutherford slapped down the third ruined starched neckcloth onto the dressing table before him. "My damned fingers are all thumbs today. Come and work one of your miracles."

The valet, busy brushing invisible lint from the green superfine coat that he was all ready to help his master into, crossed the room in some surprise. It was only on the most gala of occasions that he was ever called upon to perform his art's supreme creation: a well-tied neckcloth.

"Hif your lordship would 'old your 'ead still for one minute," he scolded a few moments later, "hit would be done and over with."

"Sorry," his lordship muttered meekly, holding his head poker still. He was nervous. By God, he was nervous! He would not be surprised to find that if he held out his hands, they would be shaking. Lord Rutherford smoothed his hands over his waistcoat and turned to reach his arms into the sleeves of the coat Jeremy was holding out for him. He would not put the matter to the test.

Well, it would all be over within the next hour or so, he consoled himself. And it was after all something he had never done before. And if it was something that every man intended to do only once in his life, he supposed he had some right to be nervous. Even if she was an ex-governess, a social nobody.

It was his own idea, he was convinced of that. He had not been browbeaten into it by his grandmother. She had been quite annoying the night before, it was true, but his mind had been made up even before she appeared on the scene. Or almost, anyway.

She had not followed his mother and Jess to the supper room. She had seated herself in the music room, occupying the chair on which Jess had sat, while he crossed to th

e abandoned violin and picked it up to inspect it. He had hoped that she would go away. A fond hope where Grandmama was concerned!

"And when might I expect you to call to pay your addresses, Charles?" she had asked archly.

He had run his thumb experimentally across the strings of the violin. Why pretend to misunderstand her? Her meaning was pretty obvious.

"Tell me more about her, Grandmama," he had said without looking up. "Who is she?"

"My dear boy," the dowager had said, "you must know far more about Jessica than I do. Every time you are in company with her you seem to get very close to her indeed. You were not offering her carte blanche again just now, were you? Very poor form, m'boy. Only marriage will do under the present circumstances. She is my guest, you know, and has been received by your sister."

"And is the granddaughter of the dearest friend of your youth," Rutherford had said, lifting the violin to his chin and drawing the bow across its strings. "Is that true, by the way? I find it hard to penetrate the tissue of lies that both you and Jess seem bent on throwing my way."

"Of course it is true," she said carelessly. "But of course you will not believe me. You owe her marriage, Charles. You have been with her unchaperoned for a quite scandalous length of time this evening, and both your mama and I have witnessed your holding her hand and kissing her. On the lips, no less."

"Tomorrow," he had said, laying the violin down at last and looking at his grandmother for the first time. "If you will engage to be at home tomorrow afternoon, Grandmama, I shall call to make my offer."

"Oh, splendid, Charles!" she had cried, getting to her feet and clasping her fan to her bosom. "I really did not think it would be quite this easy, m'boy, I must confess. But you will not be sorry. Jessica is the ideal wife for you, princess's daughter or barmaid's daughter notwithstanding. She will be at home tomorrow. You have my word on it."