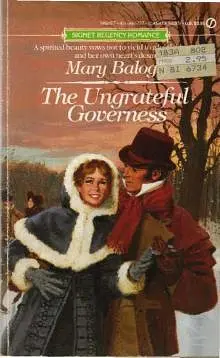

by Mary Balogh

But it was not she who had trapped him into doing it. Perhaps he would not have gone quite as soon as today, but sooner or later he would have been preparing himself for this same errand. He had known as he sat beside Jess in the music room that his words to her were quite true. He was obsessed by her. They were fated to end up together. It had been equally obvious to him that the time when she might perhaps have been persuaded to become his mistress was well past. Jessica Moore might not have a legitimate claim to move among the haute ton, but she was there now and seemed to have been accepted with remarkably little inquiry.

No, he had decided as he took her hand in his and ached to gather her completely to himself, if he wanted Jess-and he did want her, had to have her, in fact- then he must marry her. The thought should have shocked him, repulsed him. Even the thought of her resident in his grandmother's house had offended his notions of proper behavior just a few days before. But the idea came with ease and little resistance from his rational mind.

She was, after all, accepted by society. It seemed that she was not completely beyond the pale of his social milieu. It seemed likely that her father had been able to lay claim to membership of at least the lower gentry. She was educated and accomplished. Her total absence of dowry would matter not at all to him. He already had more money than one man should fairly expect in a lifetime. And she was refined. And beautiful. And very desirable. Achingly so. He did not believe he could go on living with any degree of comfort until he could somehow make her his own.

And the more he thought about it, the more he realized that it would not be enough after all to establish her in some quiet dwelling where he could visit her and enjoy her at his leisure. There would be something missing from his pleasure. He wanted Jess in his own home. He wanted to be able to take her about with him, show her off to the people of his world, take her home with him at night, or return there to her and make love to her to his heart's content without that tedious necessity of rising at dawn to return to the respectability of his own establishment.

Yes, he had decided he would marry Jess. And he had little understanding of why he should be nervous about going to make his offer to her. She wanted him too. She had admitted as much both in words and in action. And it would be a very advantageous marriage for her even if she did not. Yet he was nervous. Jess was the one woman he had ever found to be unpredictable. Their encounters never progressed quite the way he expected. He had the quite unreasonable fear that she might reject him.

Jeremy helped his master into his heavy greatcoat and handed him his beaver hat and cane. Lord Rutherford hesitated for only a moment before striding out of his room and down the branched marble staircase that led to the tiled hall below. One thing he must not do was betray any of his nervousness or uncertainty. Jess Moore had already wounded his masculine pride on several occasions. He must at least show confidence in claiming her as his bride.

"It is a great pity you are too unwell to join me in a walk, my dear Miss Moore," Lady Hope said. "It is such a beautiful day. Cold, but crisp, you know. However, I suppose Grandmama knows best, even if you do protest that you feel perfectly healthy."

"Jessica is unused to an active social life," the dowager said from the fireside chair in her own drawing room. "Often one can be exhausted without realizing the fact, and it is just at such times that exercise like walks and drives can bring on a chill. We would not want anyone to be poorly over Christmas, now would we?"

"Certainly not, Grandmama," Lady Hope said. "My dear Miss Moore." She patted the hands of the young lady sitting next to her. "How annoyed I was to see that Charles had taken you away to the music room last evening. Sometimes my brother has no more sense than a small child. And just at a time when Sir Godfrey so clearly wished to converse with you. And I thought myself so clever to take Lord Graves out of the way. I mean to have a talk with Charles."

"But I really did wish to hear the musicians," Jessica said. "It was unfortunate that we heard only part of one of their performances. Miss Lacey played before supper."

"However," Lady Hope said cheerfully, "Mama was sensible enough to bring you to join our table for supper. And did you notice how deftly I brought the conversation around to the Elgin marbles, Miss Moore? Sir Godfrey was clearly grateful for the opportunity to offer to take you to see them."

Jessica smiled. "He had talked of them earlier in the evening," she said. "Though he did warn me that it is not considered quite the thing for ladies to go."

"Pooh," Lady Hope said. "We are not such poor-spirited creatures, are we? Why, Grandmama has been to see them and professed herself quite impressed."

"Gentlemen like to see us as poor wilting females, who do not even realize the fact that they possess more flesh than what we see on their hands and faces," the dowager said. "If you wish to impress when you make this visit, Hope and Jessica, you must appear suitably shocked to discover that indeed there is considerably more."

"I shall be sure to engage Lord Graves in constant conversation," Lady Hope said. "You will enjoy having Sir Godfrey explain everthing to you, Miss Moore. He is very clearly taken with you, you know."

Jessica laughed. "And yet it was to you he first issued the invitation, Lady Hope," she pointed out.

"But of course, dear." Her companion patted her hand again. "He had to make sure that you would be properly chaperoned before he could invite you. And we are old friends, you know. He would feel that he must invite me."

Jessica smiled and said no more. Gentlemen could be left in an unenviable predicament, she felt, if they must always ask a chaperone first. What if the real object of their invitation then said no?

"Ah," the dowager said as the door opened to admit her butler. "Who is having the audacity to call on me this afternoon? Everyone knows this is not my day for visitors."

"The Earl of Rutherford, ma'am," that austere individual said, bowing woodenly before standing aside to admit the guest.

"Ah, Charles, m'boy," the dowager said, offering her cheek as he strode across the room. "What a surprise. To what do we owe this pleasure?"

"Hope. Miss Moore." Lord Rutherford did not feel one whit the less nervous now that he was there. And he would have felt far more comfortable if his grandmother had not chosen to put on this great pretence. "I trust you are both well?"

"Oh, perfectly, Charles," his sister said. "I must tell you that Faith was most gratified that you came to her soiree last night and stayed the whole evening. I do believe Lady Sarah was not displeased either."

"Lady Sarah?" Rutherford frowned his incomprehension as he seated himself.

"You were in conversation with her for all of an hour, I dare wager, after supper," his sister said archly. "I do believe she has been angling for you since last Season, Charles."

"Lady Sarah!" he said with a frown. "The chit was in her first Season last year, for God's sake, Hope. She is a mere babe. She talked to me for the whole hour last evening about her lapdogs, I do believe. At least, that is what she was talking about every time I brought my attention back to her."

"Charles!" Lady Hope admonished him. "I am quite sure you cannot be as indifferent to the charms of all ladies as you pretend to be. It would be most unfair when all the young ladies are far from indifferent to you."

"Cut line, Hope, will you?" Rutherford said. "Or I shall start making insinuations about you and Graves. You seemed to be together for much of last evening."

"Don't be absurd, Charles," she said. "What would Lord Graves see in an aging spinster like me? I was merely trying to keep him out of Sir Godfrey's way, you see, so that he would be free to speak with Miss Moore. But you had to come along and assume that she wished to listen to the music."

"My apologies!" Rutherford said, his eyes straying for the first time to Jessica, who sat with her eyes downcast. She was pleating the wool of her dress between her fingers.

"Hope, my love." The dowager duchess rose to her feet, a determined look on her face. "Every year I face the same problems as Christmas approaches. Which of my

clothes should I have my maid pack away to take with me? And what gifts will be suitable for each member of the family? It must be advancing age. I never used to give a thought to either matter. Come to my sitting room and help me."

"Me, Grandmama?" Lady Hope viewed her grandmother in some amazement. "You know you will never take advice from anyone."

"Age, my dear," the dowager insisted. "I begin to think I will have to change my habits. My brain is not as firm as it used to be."

A moment later she was ushering Lady Hope out of the drawing room. "We will not be long, dear," she said to Jessica. "Entertain Charles for me until we return, will you?"

Jessica stared at the closed door in some dismay. Then she turned suspicious eyes on the man sitting quietly across the room from her.

"Why have we been left alone?" she asked. "That was quite deliberate, was it not? Is there something going on that I do not know of?"

"It seems so," he said. He was sitting perfectly relaxed. He was even half smiling at her. "I wondered if Grandmama would prepare you. It seems that she has not."

"Prepare me?" Jessica was on her feet. She felt instant alarm.

"I am here to make you an offer," Lord Rutherford said.

"An offer?" Jessica stared at him, her hands clenched at her sides.

He held up a hand as she drew breath to speak again. "Of marriage, of course," he said. "Did you think it was carte blanche again, Jess? I would not repeat that suggestion again, my dear. And you must know that Grandmama would not conspire with me in such a case. It must be marriage between you and me." He got to his feet to face her. He smiled full at her. "Will you do me the honor?"

Jessica was staring at him incredulously. "Marry you?" she said. "You wish me to marry you? How positively absurd! Of course I will not marry you."

He raised his eyebrows and strolled toward her. "Is your answer a considered one?" he asked. "Did I not express myself well enough, Jess? Was it an arrogant proposal? Do you wish me to go down on my knees? I will, you know. And I am very serious."

"Why?" she asked. He could see that her knuckles were white, her hands balled into fists at her sides. "Why do you wish to marry me, my lord?"

"I told you last night that I am obsessed with you, Jess," he said. "We are meant for each other. I do not believe I can do without you any longer."

Jessica laughed, though there was no amusement on her face. "It must be a poweful obsession indeed, my lord," she said, "if you are willing to marry me in order to get me into your bed."

"But you feel it too, Jess." He reached out a hand and took one of hers. He held it palm up, uncurling the suddenly nerveless fingers with his other hand. "We want each other. I believe we need each other. We must marry. There is no other choice."

"Despite the fact that my mother was a scullery maid?" she asked. Her head was thrown back, her expression scornful.

He smiled, trying to keep the uncertainty out of his expression. "I do not believe that story," he said. "But yes, even despite that fact, Jess."

"Then finally we have one thing in common," Jessica said. "We are each willing to ignore the social credentials of the other. I reject your offer, my lord, despite the fact that your father is a duke."

"Why, Jess?" He was holding her hand firmly sandwiched between his own.

"I will not be anyone's whore," she said. She was staring straight into his eyes so that he could not look away. "Even with the respectability of a wedding ring. I am a person, Lord Rutherford, a whole person. I am not just a body to be used for a gentleman's bedtime pleasure. Thank you, but no."

He searched her eyes, her hand still clasped between his. Then he stood back abruptly, dropping her hand, and bowed stiffly.

"I shall wish you good day, then, ma'am," he said. "Please accept my apologies for taking your time."

And he was gone.

10

They were to leave for Hendon Park in just a few days' time. Jessica was not sure whether to be glad or sorry. She was glad that perhaps at last her future would be settled once and for all. Sorry because she was almost sure to see the Earl of Rutherford again. At least, he seemed not to have sent word to anyone that he did not intend to join his family for Christmas.

Jessica had allowed the dowager to send a letter to her grandfather. She should have written to him herself, of course. If she wanted his help-and she did-then it was only right that she be the one to write to him. Besides, it was time to patch up their quarrel. He was her only living relative, and she his. They had been fond of each other all through her childhood and girlhood. It was absurd to break all connection with each other over a stupid matter of pride. And he was not getting any younger. Perhaps the opportunity to mend their differences would not be open to her for much longer. And how would she ever forgive herself if she let the chance forever pass her by?

More than anything she needed his help. The Dowager Duchess of Middleburgh continued to shower new clothes and gifts on her and continued to extend her full hospitality. To a young lady who had been brought up to be proudly independent, it was an increasing embarrassment to accept such charity from a lady on whom she had no claim of kinship. She must let her grandfather support her, either with an allowance in her present abode or in his own home in the country.

She should have written herself. But how could she begin to explain herself to him? How strike the right note of humility without sounding servile? She had given in to cowardice when her hostess, with her usual iron-willed insistence, declared that the letter would be much better coming from her. Jessica did not know what had been in that letter except that the marquess had been invited to Hendon Park for Christmas.

There had been no reply yet. Would he come? She did not know. Her grandfather had never been given much to traveling. For this particular occasion perhaps he might. Perhaps he still loved her enough. But surely some reply would come there even if he did not arrive in person. Somehow by Christmas she would be independent again, or at least independent of all except her own family. It was something to look forward to.

And now more than ever it was imperative that she be free of her obligation to the dowager duchess. The last few weeks had been dreadfully hard to live through. It was true that she had not set eyes on the Earl of Rutherford since he had left her abruptly after his insulting offer of marriage-and neither had anyone else, it seemed. At least she had been spared that embarrassment. But she had had to face the severe disappointment of his grandmother-the same woman who was paying for her very keep.

She had returned to the drawing room with Lady Hope quite soon after Lord Rutherford's departure, but she had kept her surprise at finding Jessica the room's only occupant well concealed until her granddaughter had taken her leave. It had not taken her long after that to discover the truth.

She had been very kind. Jessica had to admit that. There was no accusation of ingratitude, no suggestion that she was no longer welcome at Berkeley Square. Quite the contrary, in fact. When Jessica, in great distress, had insisted that she must leave, whether her hostess was willing to find her a situation or not, that lady had shown uncharacteristic gentleness, patting her on the shoulder and telling her that she was a goose if she thought their friendship must come to an end merely because Jessica had had the good sense to reject "that puppy."

But she clearly was disappointed, Jessica knew. Although she rarely spoke with open kindness either to or about him, it was very clear that the dowager doted on her grandson and wished dearly that he would settle down with a wife and family. And she had wanted that wife to be Jessica. She had not pried. She had merely assumed that Rutherford had presented himself as if he were God's answer to a maiden's prayer and had offended Jessica's pride.

"Spoiled," she had said, handing Jessica her own lace handkerchief with which to dry her eyes. "Charles has always been surrounded with women ready to jump at his every bidding. Too many females in the family and not enough males. Middleburgh is no earthly good- always buried in his library or ensconced at one of his

clubs. Dear Charles has grown up with the belief that he has merely to snap his fingers and a female will come running. He is too handsome for his own good too, of course. This will do him good, Jessica, m'dear. Just what he needs."

But Jessica knew that she did not mean it. She was beginning to know her hostess rather well, and the severe outer appearance hid deep feelings. Jessica knew every time a visitor was announced that the dowager looked up expecting it to be Lord Rutherford. She knew when the old lady looked around her at any gathering that she was looking for his tall, distinctive figure. And she sensed that her hostess's enthusiasm for the various gentlemen who came to call on her and take her walking and driving was somewhat forced.

Strange as the idea seemed, Jessica became more and more convinced that the Dowager Duchess of Middleburgh had grown to love her and had wished to gift her with what was most precious in her life: her grandson, the Earl of Rutherford.

Jessica did not know where he had gone and did not care, provided only that he stayed there. She did not wish to see him ever again. And she did not like to explore the reason for her reluctance. It was embarrassment merely, she would have assured herself. How can one face and be civil to a man whose marriage proposal one had rejected out of hand? It was intense dislike. The man had had only one use for her ever since he had set eyes on her. At least his offers to make her his mistress were an honest acknowledgement of that fact.

His offer of marriage was pure insult. He was desperate enough to possess her that he would even marry her to get what he wanted. Clearly he valued marriage very little. It meant nothing to him but the acquisition of an elusive bedfellow. What would he do when he grew tired of her? Presumably by that time she would have presented him with a male heir and she could be respectably housed on one of his country estates. There would be nothing to hold him after his passion cooled, of course. Unless he discovered something of her background. He would probably be suitably impressed to discover that Papa had been the youngest son of a baronet and Mama the daughter of a marquess.