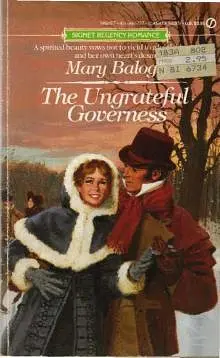

by Mary Balogh

He raised one eyebrow. "Yes, you have done very well in placing yourself quite firmly in the midst of my family, have you not?" he said. "You are to be congratulated, Jess. But have no fear for my manners, my dear. I am, I believe, always civil to ladies and to others of the same gender."

She turned sharply away from him before he could be quite sure if it was tears that suddenly brightened her eyes. He grimaced and held out his arm for her support. How could he have said what he had when the very words refuted his meaning? He felt ashamed of himself and irritated with her for causing him to feel so.

"Please take my arm," he said. "The crowds can sometimes be rough here, I have heard. Astley's attracts spectators of widely varied social status."

"I should be right at home here, then," she said coldly, grasping her pelisse and walking off in pursuit of Sir Godfrey and Lady Hope.

Lord Rutherford was left standing, his arm extended, feeling foolish. He was forced to hurry after her and protect her as best he could with a hand at the small of her back, a gesture that merely made her straighten her spine and walk on.

Damnation take the woman, Rutherford thought. One of these times-just once!-he was going to get the upper hand in an encounter with Jessica Moore.

8

The Earl of Rutherford did two things that evening that he had not done in years, and one other that he had not done in weeks. He gambled at Boodle's, a club he did not often frequent, though he had been a member for years, and won upward of three hundred pounds. He got drunk at the same club, almost but not quite to the point of incapacity. He even had an embarrassing memory the next morning, which he hoped was merely part of his night's fuddled thoughts, of delivering some sort of monologue and attempting a song. Embarrassing indeed for someone who had disappointed a mama and two doting older sisters by failing to produce one note of music by way of his vocal cords throughout his childhood and boyhood.

And he spent the murky hours between something after midnight and the twilight before dawn in bed with a woman he had no business going to bed with. He had looked in on an old crony on the way home from Boodle's, purely on drunken whim. His way had taken him past the house, and the lights were still blazing in the windows. He walked in on a party that looked as if it should have died a natural death an hour or more before. And he walked off less than half an hour later with Mrs. Prosser on his arm. Rather, he drove off in her carriage, and it was probably he who had been on her arm, he thought later, when he was trying to retrace all his activities of the night.

He could have had Mrs. Prosser years ago. He could name a dozen men who had. She was a widow and had the means and the inclination to remain so. She was willing to tell anyone who was interested enough to listen that she became easily bored with just one man. She had endured Mr. Prosser's unimaginative attentions for three years until the elderly man had had the good grace to bow out of this life and leave her free to indulge her fancies.

Rutherford had always avoided coming to the point with her. She was received by all except the very highest sticklers. He preferred to choose his bedfellows from among those women whom he would not afterward be forced to meet socially. Besides, Mrs. Prosser was an aggressive, voluptuous woman, and Rutherford liked to be totally in charge of what happened between the sheets of any bed he happened to occupy.

However, he thought just before dawn, as he stumbled home, trying to shake the fuzziness from his head and knowing that it was impossible to do-hangovers could not be shaken off at will-one could not expect to act rationally when one was drunk. Mrs. Prosser had taken him home and into her bed, and he supposed that he must have been satisfied with what happened there, because it seemed to him that it had happened more than once, perhaps even more than twice.

His valet hurried into his room, looking only slightly tousled, a few minutes after he had arrived in it. Rutherford was glad. He was sitting on the edge of the bed telling himself to remove his coat and his cravat and yet seemingly unable to lift his hands from their resting place on the bed either side of him.

"Warm water, Jeremy," he said, his nose wrinkling with distaste at the smell of some feminine perfume that clung to him. "Please," he added as an afterthought to the servant's retreating back.

The long-suffering Jeremy tucked his master into bed a short while later, fussed unnecessarily with the heavy velvet curtains that were already tightly drawn across the lightening windows, and tiptoed with theatrical caution from the room.

Rutherford groaned. He remembered now very clearly indeed why he had resolved five or six years ago never to get drunk again. The certain knowledge that he would feel wretched for all of the coming day did nothing to comfort him.

Dammit, he thought, lowering the arm he had flung over his eyes to his nose, he could still smell that woman's perfume. Mrs. Prosser, of all people. She was not at all the sort of woman he found appealing. She had seduced him pure and simple. She had taken advantage of his drunken state. Yet another reason for never getting drunk again! And where was the point of spending half a night making love with a woman when one could not afterward recall whether one had done so once, twice, or three times, or even-horror of horrors -no times at all?

But no, at least he could not be guilty of that humiliation. He could clearly recall her twining her arms around his neck as he was leaving, kissing him lingeringly on the lips, and declaring that she had not spent a more energetic and enjoyable night since she did not know when. Which said nothing about the caliber of his performance, of course, since the woman had meant to flatter, but it was at least an indication that there had been a performance.

Damn the woman! Rutherford thought, heaving himself over onto his side and wincing from the pains that crashed through his head. Damn her to hell and back. She was a nobody, an impudent, opportunistic, conscienceless nobody. And yet she had driven him into conflict with his grandmother; she had forced him into uncharacteristically unmannerly behavior; and she had pushed him into gambling, drinking, and whoring, none of which activities he had undertaken from choice.

Damn Jessica Moore!

He did not believe he was a naturally conceited man.

He had never thought of himself as arrogant. He had a sense of his place in society, yes, but then that was the way of life. Everyone around him had a similar sense, he had always believed. He had always treated servants with courtesy. He had always been charitable to those in need of charity. He had always been courteous and more than generous to his women.

Why, then, did Jess Moore make him feel like an arrogant snob? No, she did not make him feel like one. She made him become one. Of course he was outraged at her effrontery in trying to pass herself off as a member of the beau monde. Anyone of any sense and decency would agree with him. It was she who was in the wrong. Entirely so. There was no question about it. His attitude was perfectly correct. There was nothing cruel, nothing merely snobbish in his disapproval.

Why was it, then, that she made him feel so brutal? Why was it that a few cold words from her could put him instantly in the wrong? His feeling of guilt the afternoon before at Astley's had ruined the first few performances for him. He had been unpardonably rude to her and could not excuse himself even with the assurance that the provocation had been great. By retaliating with words that were so uncharacteristic of him he was merely lowering himself to her level.

Sitting next to her at the circus, Hope at her other side, Godfrey beyond her, he had wanted to take Jess's hand in his again and beg her to forgive him. She sat so rigidly upright next to him that he knew he had made her miserable. She deserved to be miserable, of course, he had told himself. And he had convinced himself; he had not apologized. Thank God, he had not apologized. But he had still felt guilty.

And very aware of her. It would have done him a great deal of good if he had had to endure rejection now and then through his adult years, he supposed. It surely could be only her rejection of him that made him want her so badly. He could not recall ever having had this all-pervading, aching

need for one particular woman.

Why should it be so? Really, when it came right down to the physical act of bedding, one female body was very much like another. Why the craving for the one woman who chose not to bed with him?

He had sat beside her, tortured by guilt and desire, until a surprising sound from beside him had caused him to turn his head and look directly at her. She was giggling. Very quietly, it was true, with one hand over her mouth, but her shoulders were shaking and her eye? twinkling. And it was definitely giggles coming fror behind her hand, not just polite laughter.

He had turned his head to the performance that had been passing unnoticed before him and saw a group of ragged clowns tripping and falling and stumbling as they rushed around about some urgent errand and constantly collided with one another. It was funny, he supposed. A child would be amused. Jessica Moore was amused.

He turned back to look at her, smiling at her reaction rather than at the antics of the clowns. She was like a child. She would never have been to Astley's before, of course. When she burst into open laughter and turned to him with the human instinct to share delight, he laughed too.

"I wonder they do not hurt themselves," she said. ''They collide with such force."

"Doubtless they practice for long hours," he said. "They are all acrobats in their own right."

But she did not even hear his answer. She had turned back to the performance and was clapping with delight.

That was not the part of the afternoon that had really confused his feelings, though, and sent him in frustration and self-hatred on his night's orgy. That had come later, when the trapeze artists had been performing.

She had been amazed, enthralled, and ultimately terrified. His own attention had been caught, too. For the space of a few minutes he had become so involved with the danger of the tricks that he lost his awareness of her. He had stared down almost with incomprehension when her hand had first stolen into his. When it had gripped convulsively and her shoulder pressed against his arm, he had covered the hand lightly with his free one. And his attention had again been effectively drawn from the flying acrobats to the woman beside him. She had watched wide-eyed and with parted lips, gripping his hand, totally unaware of his presence until the act must have reached its climax and she turned suddenly with a gasp and buried her face against his sleeve.

And then looked up at him with round, horrified eyes and down at her hand sandwiched between his two. She had stared at their hands for a stunned moment and then pulled hers away as if from some deadly snake.

"Oh!" she had said and looked back up at him. Her lips had moved but it seemed that she did not know what to say or whom to blame.

"One wishes for one's own comfort that they would work with a safety net, doesn't one?" he had said with a smile, trying to turn the moment into something quite commonplace.

He did not know what she would have said, if anything. Hope had turned to her at that moment in order to make some enthusiastic comment on the acrobats, and she had remained turned away from him for the rest of the afternoon. Somehow she had contrived to be escorted back to the carriage by Godfrey.

Rutherford turned over onto his other side in bed, but much more cautiously than he had done a few minutes before, trying not to alert his headache. Why had he almost held his breath while she clung to him and drew close to him? Why had he been afraid to move a muscle for fear that she would realize what she was doing and withdraw from him, as she had done eventually? Why must he behave as if she were important to him, as if she were someone to be wooed and won with patience and tact? She was a governess masquerading as a grand lady. A servant. A country parson's daughter. A female appealing enough to be invited to his bed, shrugged off and forgotten if she declined.

Not a woman to watch as if there were nothing else around him to see, to absorb all of his attention as if there were nothing else worth paying attention to. Not a woman whose unconscious touch was to be so cherished that he must hold himself still and breathless for fear of losing it. Not a woman to so torment his mind and his body that he must go out at night trying to free himself through the entertainment of cards, the oblivion of drink, and the drug of sexual satiation.

And now this morning, Rutherford thought with a sigh, kicking the blankets off his body and turning onto his back again, she was causing him even greater torment than she had the day before. Drinking had brought him a hangover but no oblivion. Sex, for the first time in his memory, had left him feeling soiled, nauseated, and quite unsatisfied. He had an ugly suspicion that the sort of desire Jess had aroused in him could be satisfied by no one else except Jess. And if that fact was not about to ruin his hitherto quite satisfactory life, he was a fortunate man indeed.

Who exactly was Jessica Moore? he wondered yet again. Strange to be so obsessed by a woman one scarcely knew at all. Girls have mothers too, his grandmother had said. Who had her mother been? And who had the parson been before becoming a clergyman?

It seemed that further encounters with Jess were going to be inevitable. He would dare swear she would be at Faith's soiree during the coming evening. If meet her he must, he might as well talk to her too. Find out more about her. But whether he wished to find out good things or bad he did not know. Further reason to spurn her or some hitherto unsuspected reason to see her as more of a social equal.

"Not as your fancy piece," his grandmother had said. "As your wife."

Rutherford swung his legs over the side of the bed, drew himself cautiously to a sitting position, groaned, and rose to his feet. Riding would probably bounce his head right off his shoulders, he thought, moving slowly into his dressing room to find riding clothes with which to cover his nakedness. But it seemed to be the only alternative to lying sleepless on his bed. He certainly would not be able to support the exertion of walking.

The Bradley soiree did not involve either dancing or card playing. Such activities were frequent enough at evening parties to become tedious, Lady Bradley told her grandmother and Jessica as she was welcoming them to her drawing room. Consequently, there was music in the music room for those who were interested, provided by a hired pianist, violinist, and harpist, though guests were encouraged to contribute their talents too. And there was conversation in the drawing room for those who wished to discuss politics or art or literature. Or even the weather and the state of the participants' health, she added with a laugh.

"Hope is beckoning you, Miss Moore," she told Jessica. "She is with Sir Godfrey Hall and Lord Graves. Would you care to join them? Grandmama, Mama has directed me to fetch you to her the moment you arrive."

Lady Hope was indeed gesturing to Jessica from across the room. And Sir Godfrey rose to his feet, bowed, and smiled amiably at her as she approached. Jessica scurried across to them in some relief. She felt decidedly self-conscious about attending a party given by Lord Rutherford's sister. Of the earl himself there was no sign. Surely she would not be fortunate enough to find that he would not attend at all.

"We have been telling Lord Graves about our afternoon at Astley's Amphitheater, dear Miss Moore," Lady Hope said. "And I do believe he is laughing at our childish delight in all the splendid acts. Do come and lend your voice to ours."

"I protest," Lord Graves said, also rising to bow to Jessica. "I merely smile at your delight, ma'am. I must confess a weakness for magicians myself. Do tell us your preference, Miss Moore."

Jessica took the offered seat. "I suppose the trapeze artists are the most spectacular," she said. "But just too agonizing to watch." She blushed at the memory of how she had not watched that final leap.

"You should have been sitting next to Sir Godfrey," Lady Hope said. "He talked to me the whole time and calmed my nerves wonderfully well. I declare he does not have a nerve in his body at all. And I daresay he would have preferred to sit next to you too as it was you he invited first. Foolish of me to sit between you. I would have done just as well next to Charles."

"My dear ma'am." Sir Godfrey looked somewhat taken aback. "I i

nvited both you and Miss Moore to accompany me to Astley's. And indeed, I must say that I found your very sensible conversation calmed my nerves during the trapeze act."

"Well, is not that a foolish thing?" Lady Hope said with a laugh. "Lord Graves, would you be so good as to escort me to the music room? I really do love harp music, and one gets to hear it so rarely."

Lord Graves jumped to his feet and held out his arm to her. She flashed a smile at Sir Godfrey and Jessica.

"I do hope you do not think me rag-mannered to leave you to each other's company," she said. "But I am sure you will not mind."

Jessica could not decide whether she was more amused or dismayed at being left thus. Lady Hope seemed to have convinced herself that she and Sir Godfrey would make a good match and was making every effort to throw them into company together. She decided on amusement when Sir Godfrey smiled comfortably at her.

"I can see that you are having the same thoughts as I, Miss Moore," he said. "Lady Hope has been trying to marry me off for the past five years or more. It seems that you are her latest candidate. I hope you will not be embarrassed by her attempts. I find them amusing and somewhat endearing. Shall we be friends so that we may be comfortable together even when she is at her least subtle?"

Jessica laughed. "I thank you for your plain speaking, sir," she said. "And yes, of course, I had noticed and was hoping desperately that you had not. I am told, sir, that you have fascinating stories to tell about your travels if you are sufficiently assured that your audience is interested. Will you share some of them with me?"

"My dear ma'am," he said with a smile, "are you quite sure? I find that people who prose on about their experiences on the Continent can be dreadfully boring. Everyone seems to feel that a year or two spent abroad qualifies him to describe with perfect accuracy the national character of the Italians or the French or whoever it happens to be."