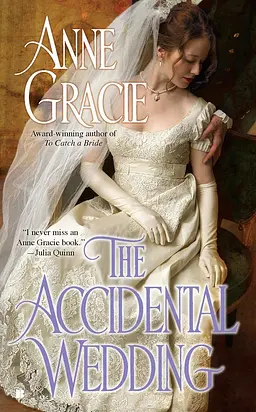

by Anne Gracie

It was a problem. The moment he told Maddy he had his memory back, she’d insist he leave. Especially since, as it turned out, he had a large house down the road with a dozen beds or more. Why would she let him remain in her bed?

He liked being in her bed. He liked it more than he should.

More than he had with any other woman.

In fact . . . it slowly dawned on him . . . he didn’t want to leave her at all.

How the hell had that happened?

He’d always kept his dealings with women light—no strings, no commitment—choosing as his paramours ladies who wanted it that way as well. It was his rule: light, superficial fun, and nobody getting hurt.

This . . . this whatever-it-was with Maddy Woodford wasn’t light or superficial at all. It was heading into seas he’d never navigated before, seas he’d managed to steer clear of his entire life, and he wasn’t about to start now.

But if he realized the danger in time—and he had—he could act.

Thank God he’d gotten his memory back. Forgetting his own name wasn’t nearly as bad as forgetting the danger Maddy Woodford posed to his peace of mind.

Thank God she’d had sense enough to stop him when he’d tried to entice her into making love. A few kisses didn’t matter, even if kissing her affected him like no other kisses had. It was probably a side effect of the amnesia.

He could still get out, save himself, save them both from an entanglement neither of them needed. He would. He’d go to Whitethorn this very afternoon.

But what if Maddy and the children faced another night of terror?

Dammit, he couldn’t let that happen.

No choice, really. He had to stay on here. He’d set a trap, catch the bastard, and get him securely locked away, transported to the other side of the world. Then Maddy and the children would be safe and he could leave with a clear conscience.

He’d keep the recovery of his memory to himself a little longer. It wouldn’t be a lie, exactly, just a withholding of the whole truth.

And in the meantime, he’d make sure he kept the luscious Maddy Woodford at a safe distance.

“Miss Woodford, this is for you,” he said when Maddy returned to the cottage. He handed her a banknote.

She took it without thinking, but when she looked at what she had, her jaw dropped. “Ten pounds? What for?”

“Call it bed and board.”

She stared at the crisp new banknote. “Ten pounds? But that’s a ridiculous amount for a few days’ accommodation and food—you’ve hardly eaten anything anyway.”

Why was she arguing? He had money, and God knew she needed it. But ten pounds was a huge sum for three nights in a bed and a bit of soup and stew.

Ten pounds was more than the annual salary for a maidservant.

And he had a head injury. She didn’t want to take advantage.

“Take it,” he said, “and let there be no more talk of sending me to the vicar’s.” He saw her expression and added, “Just until I get my memory back, of course.”

“I see—it’s a bribe.”

“Perish the thought!”

“But if the vicar asks me directly, you expect me to lie.”

“Of course not,” he said suavely. “I trust you will answer in your own, er, unique manner.” His blue eyes danced.

He meant she lied by omission. She did. She wished she had some moral ground, high or otherwise, to stand on, but she didn’t.

The banknote crackled appealingly between her fingers in a small papery siren song. She couldn’t give it back, she just couldn’t.

“Don’t look at me like that,” he said. “It won’t be long before my memory returns, I’m sure. Already I’ve had a few small flashes—nothing important, but I’m sure it’s just a matter of time.”

“I will accept it, thank you. But you must ensure you aren’t seen by any of the villagers.” There would be scandal if anyone found out. An unconscious man was one thing: a handsome and obviously virile gentleman was quite another.

But homelessness was worse than any scandal.

Not that it would come to homelessness. She would return to Fyfield Place before she let the children starve or live on the streets. Since Mr. Harris’s visit, the prospect of returning had hung over her like an ax waiting to fall.

With this ten pounds, she was safe, for a time. Just until he got his memory back.

She tucked the money away in the tin, adding it to the seven pence that until ten minutes earlier had been all that stood between her family and complete destitution.

Ten pounds would feed her and the children for months. It would pay for new shoes for children outgrowing theirs at a rate she couldn’t keep up with.

But she could grow food, and the shoes would have to wait. This was rent, this would keep them safe. When Mr. Harris returned tomorrow, she’d be able to pay him.

Thank God.

In the meantime she’d write to the Earl of Alverleigh and put her case before him.

“Thank you,” she said again to Mr. Rider. “The money will make all the difference in the world.”

“What’s worrying you?” Nash asked Maddy. She’d spent the last half hour sitting at the table composing a letter. Now it was sealed and she was pacing up and down, looking frustrated.

“I’ve written a letter to the Earl of Alverleigh, who’s acting for my landlord while he’s out of the country,” she told him, “but now I don’t know where to send it. I know it’s Alverleigh House, but in what county? Near which town or village?”

“I see your point.” Nash frowned, pretending to consider the problem. His first small, ironic hurdle. How to give her his brother’s address without revealing his own identity?

“I told Mr. Harris I would write, and he said to give it to him and he would forward it, but I don’t trust him.”

“No, no, quite right. Would the vicar have a copy of Debrett’s, perhaps?”

“Debrett’s?” She glanced at him in surprise.

“Debrett’s Peerage. It’s a guide to all the best families in the kingdom—”

“Yes, I know what it is, but . . . you remembered it.”

“Oh. So I did.” He examined his fingernails. “Must be stored in the same part of the brain as Hadrian and his wall. I don’t pretend to know how it works.”

“Don’t worry,” she told him with warm sympathy. “I’m sure it will all come back to you soon.”

She looked so beautiful, so concerned for him. Serpents of guilt coiled around Nash’s conscience, squeezing it tight. He beat them off.

“I’m sure the vicar will have Debrett’s. It’s the kind of thing he’s interested in—he’s a bit of a snob. I’ll call in on the way to the village. The children will be finishing their lessons, so it’s perfect timing. I’ll post the letter in the village and deliver Mrs. Richards’s hat at the same time.”

He had to get to that letter before she tucked it in her reticule. A small delay was called for . . . He peered at the window. “Looks like more rain on the way.”

She looked out the window. “Do you think so?”

“Definitely. Those sort of clouds come up very quickly. But if you don’t mind your nice dry washing getting soaked . . .” He shrugged.

“You might be right. I’ll bring it in.” She put down the letter and hurried outside.

The moment she’d gone, he slid out of bed and, in two hops, reached the table. The letter was sealed with a simple blob of beeswax. He heated a knife in the fire and sliced the seal open. Around the neat margin she’d left, he scrawled a note to his brother.

Marcus, was injured but am recovering. Give Miss Woodford whatever she wants. Am at her cottage incognito. Funny business going on. Boots slashed, send new ones urgently. Nash.

He underlined “incognito” twice to emphasize the need for discretion, and “urgently” once to emphasize the need for boots. Then he blew on the letter to dry the ink, refolded it, and resealed the letter.

By the time she brought the washing in, he was bac

k in bed looking innocent and bored.

“I won’t be long,” she told him. “If I can get this letter in the post today I’ll be very pleased.”

Without Maddy and the children, the cottage was very quiet. Nash should have welcomed the peace but he couldn’t stay cooped up a moment longer. A jar would no longer do; he needed to visit the outhouse.

He swung his legs out of bed and cautiously put his foot to the floor. It hurt a bit, but if he didn’t overdo it . . .

He took a few steps around the cottage, limping to favor his sore foot.

The stone floor of the cottage was icy. Lord knew why anyone wore a nightshirt, he decided: freezing draughts crept under the blasted thing, wrapping around his thighs and chilling more personal parts.

However did women stand it?

He found his clothes and dragged on a pair of drawers, breeches, woolen stockings, and his one surviving boot. Better, but still very cold. Colder outside. He shrugged into his coat, then hopped to the back door.

There he found the ugly pair of working man’s boots that Maddy wore for working outside. He shoved the toe of his injured foot into one, and limped out to the outhouse.

By the time he came inside he was shivering. He added a small log to the fire. A week ago he would have built a really good blaze. He loved a roaring fire, loved watching the flames dance and the sparks fly. There was a primitive satisfaction in making a fire roar.

But Maddy and the children had to gather the fuel themselves, wandering the forest in search of fallen timber, then dragging it home, chopping it as needed.

On that thought, he went back outside, found the ax she kept just inside the back door, chopped up the rest of her wood, and stacked it neatly by the back door. The combination of exercise and cold, fresh air got his blood moving again. He felt better than he had in days.

He prowled around the cottage in a kind of hop-limp, looking for something else to do. It was remarkably bare. Every item it contained had a utilitarian purpose, except for a handful of very amateurish and crudely framed watercolors that hung on the walls, signed Jane Woodford and Susan Woodford. Susan’s were rather good.

He was about to return to the hearth when he noticed a small, brown leather case tucked away on a corner shelf. His curiosity was instantly roused. He hesitated. As a guest, he should respect his hostess’s privacy. But he wanted to discover why she was being harassed by an imitation ghost and a bullying estate manager. The case could contain useful information.

Or so he told himself.

He brought it to the fireside to examine the contents. He found an unframed miniature carefully wrapped in a beautiful piece of antique brocade, a portrait of an enchantingly pretty girl in the costume of last century, with powdered hair piled high. Who was she? He rewrapped it carefully.

He found an old bible, in French, a battered tin containing a sixpence and two ha’pennies, an old-fashioned doll, and something wrapped in the same antique brocade as the miniature: a hand-bound sketchbook.

The sketchbook was fascinating, dozens of drawings and watercolors executed with a skilled amateur hand. He turned the pages carefully, flicking over the landscapes, and stopped, riveted, when he came to one of an earnest young girl. Maddy as a child, a vivid little face, with that same expression of faint anxiety lurking in her eyes.

He found another sketch where she was sitting with a thin-faced old lady with a careworn expression and severe, upright bearing. Her grandmother?

There was a delicate drawing of a tiny babe with a wizened, ancient face and eyes he somehow knew had never opened on this world: a portrait of grief.

There was a story here . . .

He examined the landscapes with greater interest now; a crumbling ruin of a castle, lovingly detailed; the garden of a small, rural cottage, a laborer’s cottage like this one and, in the foreground, the spare, upright figure of an old lady, veiled and gloved like a beekeeper; a few exquisitely rendered studies of wildlife—flowers, a fawn caught on the edge of a forest, a bee delving into a lavender flower. He rewrapped the sketchbook, his mind full of questions.

The last thing in the case was a cheaply bound, thick notebook tied with a faded ribbon. Curious, he untied it. Pages and pages of writing, French, in a round, girlish hand. A diary. The ink had started to fade at the edges but phrases jumped out at him.

He will be tall and handsome and very charming more charming even than Raoul and he will kiss my hand as if I am a princess and lead me onto the dance floor Grand-mère says he will come that I must be patient but nobody ever comes here and she says she read it in my tea-leaves but we never have tea anymore only tisanes and who ever heard of reading a fortune in a tisane?

He smiled at the rush and tumble of her thoughts, so young, so impatient, dreaming as he supposed all young girls did, of Prince Charming. And who was this charming Raoul? He flipped a few pages.

. . . all this practicing. I grow so weary of it, as if there is any point to it. Papa said Grand-mère was cracked in the head and perhaps she is . . .

. . . If I were a boy, Papa would love me, too, and I would not be here in a woodcutter’s cottage, treading forgotten measures in secret with no partner, to music I’ve never heard, hearing tales of people killed before I was born. I love Grand-mère but must I dwell with ghosts all my life? I want—

Voices, Nash suddenly realized, outside. Dammit! Foot-steps heading this way. No time to look out of the window. If she had visitors with her, he’d best be invisible.

He shoved her things back in the case, slammed it shut, and slid it across the floor to sit under the shelf he’d found it on. He dived into the bed, hitting his injured ankle on the wooden frame as he did so. It hurt like blazes.

His clothing! He pulled off his coat and started on his boot. It fitted so snugly it was a struggle, and when he heard the rattle of the latch he thrust his booted foot under the bedclothes, tugged the bed curtains closed, and lay back, just as the door opened. If it was that blasted vicar again . . .

But it was just Maddy and the children.

“You were right,” Maddy said as she removed her hat. The children clattered past her and raced upstairs to change out of their good clothes. “The vicar did have a copy of Debrett’s, so I addressed the letter and then, as luck would have it, the mail coach rolled into the village ten minutes after I posted the letter. So it’s on its way to Hampshire. That’s where Alverleigh House is.”

She moved briskly around the cottage, straightening things. She suddenly paused and surveyed the room. “You’ve been up,” she said, looking pleased. “Moving around. How wonderful. You must be feeling a lot better. How is your ank—” She broke off, noticing the small leather case out of place. One of the fastenings was undone. Her smile faded. “You’ve been looking at my things.”

“I’m sorry, I was bored.”

Her brandy eyes flashed. “Being bored is no excuse for snooping.”

“I wasn’t snooping,” he said uncomfortably. “I was just . . . exploring.”

“Exploring my private things!” She made it sound like he was going through her underwear.

“It wasn’t like that at all. I was just . . .”

Maddy opened the case. There, on the top, was her girlhood journal, the ribbons that fastened it loose and untied. If he’d read her journal, full of her silly, precious, girlhood dreams, she would just die of mortification.

“Did you read my—can you read French?”

His eyes flickered guiltily. He had. He’d read her journal.

He said, as if it were an excuse, “I didn’t mean to. I can read French—it’s much used in dipl—” He caught himself in time. “A few phrases jumped out at me. I promise I read no more than that.”

“Only because I came home.” The look on his face told her she was right. How dare he go poking and prying in her private things. Was this how he repaid her for all her care of him? To violate her privacy? She wanted to cry. She wanted to hit him!

“It was wrong to open t

he case and I apologize. Unreservedly. I didn’t read much of the journal but I did look through the sketch book. I wondered—”

She flung up a hand. “Not another word!” If he said one more thing she would hit him. How dare he wonder? He who had no history, no past. How could he know how painful some memories were?

She jammed the case into its little alcove. “I knew accepting money from you would complicate things. I suppose you think it gives you the right to—”

“It has nothing to do with the money. I wouldn’t dream of holding it over your head in such away. That would be despicable.”

“And looking through my belongings while my back is turned isn’t?”

There was a small silence. “You’re right, it is. I’m sorry.”

He looked sorry, too, which mollified her somewhat. But not enough. He’d read her journal . . . She felt stripped bare.

He sat on the edge of the bed watching her as she began preparing the next meal. After about ten minutes she happened to glance at him.

“Forgive me?” he said instantly.

Maddy sniffed. Lying in wait for her, pouncing with a smile guaranteed to dissolve all remnants of anger, a smile too charming to resist. He knew it, the beast. “If those boots have torn my sheets, I’ll have you out of here and up at the vicarage as quick as you can say Jack Robinson, ten pounds or no ten pounds.”

“Boot,” he corrected her. “You mangled the other one to death, remember. And the sheets aren’t torn, so you needn’t send for Rev. Prosy.” His eyes danced; the wretch knew she was bluffing.

“You should be grateful I did ruin your boot. I could have left you to freeze in the mud.”

“But you didn’t,” he said softly, “and I’m ever so grateful.”

There should be a law against a voice like that. His coat lay on the bed beside him. She picked it up and hung it on a hook. It was bound to pull it out of shape, but did she care? Serve him right if he had to wear a shapeless rag when he finally left her house. She didn’t own a wardrobe, a chest of drawers, or even a hanger. But the vicar did.