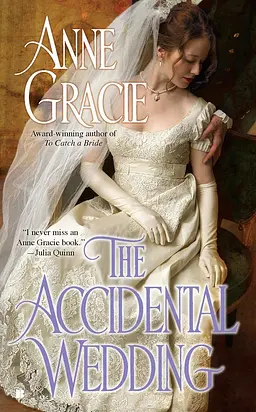

by Anne Gracie

His brows rose. “The Bloody Abbot?”

“The ancient ghost of an abbot who was killed trying to prevent Henry the Eighth’s men from destroying the religious carvings at the abbey. The village is very proud of him. But I don’t believe it.”

“You don’t believe in ghosts?”

“This is definitely no ghost, just a man.”

“Men can be as dangerous as ghosts, more so.”

As if she didn’t know that. But dangerous men didn’t only bang on windows in the night. Some of them trapped you by other means, spooning their long, strong bodies around you in the night and dizzying you with long, sweet, addictive kisses.

He held her still, his long fingers imprisoning her wrist lightly, effortlessly. She tugged it for release. “I have to go.” While her willpower lasted.

His gaze locked with hers as slowly he lifted her wrist to within a hairsbreadth of his mouth, so close she could feel the warmth of his breath on her skin. She couldn’t look away, suddenly, absurdly breathless as, without breaking his gaze, he turned her hand over and kissed her slowly in the heart of her work-worn palm. The sensation shivered right through her. Without conscious volition, her fingers closed to cup his face.

“I’ll find this false ghost of yours,” he promised her, his voice husky, knight to maiden. “I’ll get him, don’t worry.” He kissed her palm again, and again delicious shivers rippled through her body.

She ached to sink back into his embrace and lose herself in more of those deep, drugging, devouring kisses. She longed, just once, to forget about her problems and responsibilities and lose herself in sensation, letting a man, this man, make love to her.

Even if he was a rake, even if the love was counterfeit. She wanted, just once, to have the morning dream come true.

But if she did, she risked losing herself altogether.

She steeled herself to pull away from him and slid out of the bed. The sharp chill of the stone floor brought her to her senses.

Her blood might be singing with pleasure and excitement, and her foolish heart yearning after impossible dreams, but this was dangerous, too dangerous for a woman in such a precarious position.

She had to keep him at arm’s length. Further. She could feel the imprint on his mouth against her palm still. Her fingers were closed protectively over it, as if they could keep and cradle his kiss forever.

If anyone in the village had the slightest idea of what had happened in the bed this morning . . .

Her good reputation was the fine slender thread that connected her in friendship to the villagers. And without their friendship—and their custom for honey, hats, and eggs—she and the children could not survive.

While the few people who knew thought him a helpless invalid, she was safe.

But he was no invalid now. She had to put a stop to it, before she allowed any further liberties.

“When my head is no longer a blacksmith’s anvil, we’ll try that again,” he murmured with a faint, wry smile.

She turned and found him watching her, the way a cat watches a mouse it has already trapped, possessively, with leashed anticipation.

It was as if he’d dashed a bucket of cold water in her face. He knew nothing of her position, and from his expression, he didn’t care. He was a rake.

And she was a stupid, dreamy fool.

“And will that be soon?” she asked.

He gave her a crooked, altogether wicked smile. “I certainly hope so.”

“Good.”

“Good?” His smile broadened.

“Yes, for as soon as your head is not a blacksmith’s anvil,” she said sweetly, “you will leave this house.”

For an instant, it wiped the smug look from his face, then he rallied. “I can’t. Where would I go? I have no memory, remember?” His piteous expression was patently feigned, his tone so ripe with confidence it enabled her to harden her heart.

“Where would you go?” she echoed. “To the place in the parish where any poor, lost soul is welcome, of course.”

He blinked. “You’d never send me to the workhouse.”

“Of course not. You have too much money. You’ll go to the vicar’s.”

His brows snapped together. “That prosy old bore’s? Impossible.”

“No, it will be quite easy,” she assured him, willfully misunderstanding. “He has a carriage with which to convey you. It’s very well sprung. It will hardly bump your aching bones at all.”

“I won’t go.”

“You won’t?” She arched an eyebrow at him.

“I can’t. I’m—I’m allergic to clergy. And windbags. And fruit bowls.”

She laughed. “Nonsense.”

“It’s true,” he said earnestly. “I come out in . . . hives . . . and . . . boils at the merest whiff of a sermon.”

“But how can you possibly know that, Mr. Rider,” she said sweetly, “when you don’t even remember your name?”

He shrugged. “It’s like Hadrian’s Wall, one of those odd things I remember.”

“Very odd. And quite irrelevant, I’m afraid. The minute you’re able to move, I’m taking my bed back.”

“You’re more than welcome in it. Have I not made it clear?”

“On the contrary and that’s the pr—” She stopped. She was not going to get into a debate with him.

“You’re running scared.” His gaze dropped briefly to her breasts and he smiled.

Aware that her nipples had hardened in the cold, she folded her arms over her chest. “Of what, pray, am I scared?”

He sat back against the pillows, folded his arms behind his head, and grinned. “You liked what’s been happening in the bed and you’re afraid that next time you won’t have the strength of mind to stop.”

Well, of course she was. She was only human, wasn’t she? Her body, even now, was urging her to leap back into the bed and let him finish what they’d started, but she—thank God!—was in the grip of cold, hard reality.

“Nonsense,” she said, and it sounded feeble, even to her own ears. “The moment you are well enough to be moved, you will go to the vicar’s. My mind is made up. Now, I need to get the children ready for their lessons—”

“Ohhhh!” He groaned suddenly and doubled up.

“What?” She hurried closer to the bed. His face was screwed up with pain. “What’s the matter?”

He opened one bright blue eye and said in a perfectly normal voice. “I’m having a relapse.”

She fought a smile. “You’re impossible. And you won’t change my mind.”

His eyes danced as he gave another artistic groan. “I’m allergic to clergy. Vicars give me vertigo . . . priests give me palpitations . . . and bishops make me bilious.” He added in an unconvincingly feeble voice, “I might be stuck here for weeks . . .”

“In that case, I’ll call in the vicar for the laying on of hands.” She pulled the bed curtains closed with a snap.

His voice followed her into the scullery. “He’d better not lay a hand on me! He poked a finger in my ribs yesterday in a thoroughly unfriendly manner! If he tries it again, I’ll punch him, man of the cloth or not.”

Maddy grinned. He was a devil, to be sure. She put the oatmeal on to cook, washed and dressed, and went upstairs to wake the children.

“Can I take Mr. Rider his breakfast?” Jane asked when the porridge was ready.

“You did it last time,” Susan interrupted. “It’s my turn.”

“I’ll take it,” John offered. “I’m sure he’d rather have a man—”

“You can all take it,” Maddy interrupted before the squabble could start. “Jane, take the tray with the porridge, Susan, take the honey, Henry carry the milk jug, and John give him his willow-bark tea. Tell Mr. Rider he can add more honey if it’s too bitter.”

“Amazingly enough, Mr. Rider can hear through the curtain,” a deep voice said.

“I want to take something, too,” Lucy spoke up.

“Yes, of course, you must take his napkin

.” Maddy handed it to the little girl, who marched importantly to the bed, stool for climbing on in one hand and napkin in the other.

Maddy waited for the children to stop fussing over him and return to the table. They were as fascinated with him as she was. He was so wretchedly charming. Quite impossible to resist.

But she had to.

Even when he was unconscious, she’d been drawn to him.

She hadn’t known him at all, hadn’t known that his eyes were bluer than a summer sky in the evening, that they could tease and dance with mischief, and suddenly turn somber as the night. Or that blue could burn with an intense light . . .

And yet she’d slept three nights with his body against hers, feeling—quite illogically—safe with a stranger in her bed.

Worse, she’d assumed it would continue to be safe once he came to his senses. Because he was a gentleman.

Madness! He was more dangerous than ever now. And in ways she would never have realized.

Who could see danger in watching him in serious conversation with two small boys, allowing them to tell him things about horses he’d probably known forever, not letting on for an instant that he was tired or bored or in pain?

But there was. There was danger in the way he smiled and thanked Jane or Susan for fetching him a cup or taking a plate, making little girls feel important and appreciated.

Lucy was quite possessive of him, certain it was her kiss that had awakened him. And though it was clear he’d had little to do with children, he hadn’t dismissed her childish notions but responded with grave kindness that had the little girl glowing with pride.

He’d ignored his own injuries to protect them from an intruder. He must have known firing the gun would cause him pain, but he never hesitated.

Before, she didn’t know the kind of man he was.

She didn’t know it now, she reminded herself. She still knew nothing about him.

Only that he was kind to women and children. And chivalrous. And stubborn. A gentleman. And there was the rub. He was a gentleman, to his clean and well-tended fingertips.

But also a rake.

Even though she knew little about him, she could tell he didn’t belong in her world. And she didn’t fit in his and probably never had.

He had excellent manners. Was protective, gallant. Funny. Handsome.

Dangerous.

The lure, the lie of Prince Charming, she reminded herself. Women had a fatal tendency to see romance in men and situations where there was none. It was why Grand-mère had made Raoul wait for two years . . . Protecting herself from her own fatal tendencies.

Of course Mr. Rider was nice to her and the children—he had nothing else to do, nowhere to go. His very survival was dependent on their kindness.

He was just a man. But for her, dangerous.

She needed him gone. Her life would be drabber, less exciting, but her heart would be safer.

The door flew open and Maddy put her head in. “Hide! Mr. Harris is coming.”

Who the devil was Mr. Harris? He looked around for a place to hide. There was only the scullery and it was too cold to be cooling his heels out there for who knew how long. He climbed back into the bed and drew the curtains.

He watched through a gap in the fabric. Harris was about forty, solidly built, but his breeches were too tight, his coat too bright, and his thinning hair, once he carefully removed his hat, had been teased and pomaded and trained carefully over a bald patch.

A suitor? He was far too old for her, not to mention too damned ridiculous.

Harris entered the cottage and seated himself at the table without being invited. His confidence, almost an air of ownership, was annoying. He came straight to the point. “I’ve received instructions from the new owner—”

“I thought you said he was out of the country,” she interrupted.

He gave her a tight look. “That’s right, Russia. But he sent instructions to his brother, who has his power of attorney.”

“His brother?”

“The Earl of Alverleigh.” Harris turned his head. “What was that? Is there someone here?”

Behind the curtains, he stiffened. Damn. He must have made a sound. But the Earl of Alverleigh? The name meant something. But what?

“Who would there be?” she asked Harris. “Now about this letter—”

Harris didn’t respond. He stared at the alcove, his brows knotted with suspicion. “Have you got someone in there?”

She made an impatient gesture. “The children sometimes play there. Perhaps Lucy is taking a nap. What does it matter? Did you inform the new owner about the promise Sir Jasper—”

“Five pounds by the end of the week.”

Her jaw dropped in dismay. “Five pounds? But I don’t have five pounds.”

“Then you’ll have to leave.”

“Leave? But I can’t poss—”

“Five pounds by the end of the week, or you’re out. Mr. Renfrew’s letter was adamant.” The chair creaked as Harris leaned back, obviously savoring the moment.

“But that’s tomorrow.”

Harris shrugged.

“Who is this Mr. Renfrew? I need to speak with him.”

“The Honorable Mr. Nash Renfrew is the new owner. He’s Sir Jasper Brownrigg’s nephew and brother to the Earl of Alverleigh,” Harris said with ill-concealed satisfaction. He kept speaking, but his words seemed to fade away.

Renfrew? The Earl of Alverleigh? The little world of the bed in the alcove seemed to spin. Renfrew . . .

Nash Renfrew . . .

He’d seen an avalanche in Switzerland, once. First a tiny, almost invisible fracture, and a small piece of snow had slipped. An odd sort of ripple had followed and snow had started sliding, first in ribbons, then in ragged sheets, until suddenly an entire mountainside was falling, tumbling, the landscape shattering downward at a terrifying speed, taking everything with it.

And afterward a terrible, echoing silence.

His memory came back like that, a tiny fracture that started with his name, Nash Renfrew.

He was Nash Renfrew. And his brother was Marcus, Earl of Alverleigh.

And suddenly his brain was filled with ribbons, sheets of memory: names, faces, moments, smells, all reconnecting, swirling, crashing, falling into place like a mad puzzle that had been tormenting him elliptically for days, and now, finally, began to make sense.

He wasn’t sure how much time had passed while it was happening; in some ways it felt like hours, yet it was over in a flash. A bit like the avalanche.

And afterward he was left almost as shattered, as he began to put it together, put himself together.

His name was Nash Renfrew and he was coming home from . . . no, not coming home. He was going to see Uncle Jasper’s estate. Someone had written—Marcus? No, some lawyer, he thought, to say that Uncle Jasper had died. Nash had known for several years that he was the heir. Whitethorn Manor was unentailed, Jasper had never married, and Nash being a younger son, had little property of his own.

So he was riding to Uncle Jasper’s estate . . . no, that wasn’t right. One didn’t get off a ship and ride a horse right across the country. He’d just come back from . . . from Russia, from St. Petersburg. No, that was wrong, too. He’d gone to London first, and then visited Aunt Maude in Bath before he left, left . . . for . . .

The house party! He nearly spoke the words aloud. He’d almost forgotten he wasn’t alone, that discretion was crucial. He was Nash Renfrew and discretion was his middle name.

He peered out between the curtains, but Harris was gone. Maddy was wrapping herself in a cloak, her face set and grim.

“Maddy,” he said, “I must tell you—”

“Later,” she said brusquely. “I have to go out.”

“But I have my mem—”

The door closed behind her.

Nash didn’t mind. He’d tell her when she returned. Power surged through him. He was himself again, in control, no longer a helpless creature with no idea of who he w

as. His physical injuries were irrelevant now. They would heal. He had himself back and that was what counted.

Bizarre how knowing one’s identity mattered so very much.

Nine

He had his memory back. He was himself again. And to Nash’s frustration, there was nobody here to tell.

He recalled Maddy’s frequent questions about who would be worrying about his non-arrival. The answer was nobody.

From London, he’d called on Aunt Maude in Bath, and after her, his plan was to drop in on Harry and Nell at Firmin Court on his way to Whitethorn Manor. A rapid but thorough inspection of his inheritance, make any arrangements necessary, then back to London for the ball and the grand duchess.

And then . . . possibly . . . a wedding.

In Bath he’d run into an old acquaintance who’d invited him to a house party near Horningsham. But he soon realized the house party was simply an excuse for evening bed games and no place for any potential brides. Nash had no interest in random and indiscriminate coupling, and since Horningsham was only a day’s ride across country from Whitethorn, he decided to ride ahead and arrive early at his new estate. He’d sent his valet on to Harry and Nell’s. So nobody was expecting him anywhere until next week at least.

He wished Maddy hadn’t run off; he wanted to tell her the good news. Not just that he’d gotten his memory back, but that he was her new landlord and her worries were over. She could stay here rent-free for the rest of her life. It was the least he could do for the woman who’d saved his life.

If only she’d waited one minute . . .

What instructions?

Harris’s exact words had been I’ve received instructions from the new owner.

Nash hadn’t had any correspondence with Harris at all, least of all about raising rents. If Harris was lining his pockets with illegal rent increases, he was in for an unpleasant surprise.

Was Harris the “Bloody Abbot,” and if so, why? Making money on the side, Nash could understand, but terrorizing a woman and children? And while Maddy and the children were in the slightest danger of being terrorized again, Nash couldn’t leave them.