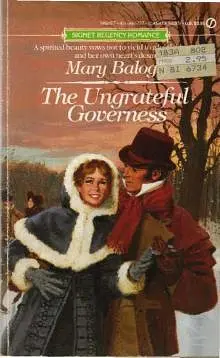

by Mary Balogh

But he had not said any of those things. She had stopped him. She had told him they would not suit. She had told him that there was nothing in him that she could esteem. He could not recall her exact words, but that was what she had meant. He had felt almost blinded with hurt. To be told by anyone that one is worthless is painful. To be told that by someone one loves is almost unbearable.

What had he done? How had he reacted? Had he become angry immediately? He knew he had become angry. He had even threatened to strike her. But no, he had not lost his temper right away. He might as well have, though. He had turned high-handed, pointing out to her with bull-headed arrogance that she had no choice but to marry him. If anything could be more calculated to make Jess Moore quite immovably determined never to marry him, it was just such an argument. And he had used it to the full!

What a fool. What an utter fool! Lord Rutherford took a long and uncomfortable look at himself through the eyes of Jessica and shuddered. Had he ever once in their whole acquaintance asked her what she wanted? As a governess she must wish for the unexpected delight of a night spent in his bed. As a dismissed employee she must receive with gratitude his flattering offer of employment as his mistress. As a young guest of questionable social status in the home of his grandmother she must accept with alacrity his condescending offer of marriage. As the compromised young granddaughter of a marquess she must rush with relief to the haven of his arms away from the jaws of scandal.

Oh, yes, he had never done anything to Jess against her wishes. He had said something like that to her a few minutes before, had he not? So self-righteous! He could even say with some truth that he had frequently acted with her own interests in mind. But had he ever thought of asking her-and waiting to listen to her response- what she wanted of life? Must he always be telling and assuming? It was the habit of a lifetime to behave as the lord and master, he supposed.

And now he had lost his final chance with Jess. There could be no more. She had made it very clear to him on two occasions that she wanted none of him, and this time he must respect her wishes. It was the only way he could prove his love for her. It was still true that according to all the rules of society she must marry him, and without delay too. But really, what did society's rules amount to in this case? Who would expose Jess's terrible indiscretion to the ton? Grandmama? The Marquess of Heddingly? No one else knew.

The Barries when they arrived during the spring could create some nasty gossip, he supposed. But it would not matter. Jess would not care. He really believed that she would not care. Or if she did, she would still consider the gossip preferable to marriage to him.

The Earl of Rutherford winced.

He must go away. He must talk to her grandfather, explain that they were not to marry and that no pressure must be put on Jess to change her mind. And then he must leave. She must be free to do with her life what she decided to do, with the help of her grandfather. He must stay away from her.

Perhaps in a year's time, or two… But Lord Rutherford turned decisively toward the door of the library. No, not even then. He had always lamented the fact that he had been unable to travel abroad when he was a young man. He would go now. During the spring.

And he would stay away for two or three years. Long enough certainly for them both to forget. He would stay away and keep temptation at arm's length.

He would leave the following day, Rutherford decided as he left the library. He would have liked to saddle a horse and gallop back to London at that very moment. He could be back long before dark if he did so. But he could not leave the day after Christmas. The whole family would be upset. Everyone would know that something must have happened. And some might begin guessing. He did not want that to happen. He did not want anything to cause possible embarrassment to Jess.

"Jessica, my dear girl, do come along to my sitting room with me," the Dowager Duchess of Middleburgh said, laying a hand on Jessica's arm after luncheon. "The trouble with the members of this family is that they forget I am an old woman and unable to stand the noise and constant motion of their merrymaking. What I need is an hour of peace and quiet with someone sensible to converse with."

It seemed reasonable to Jessica. She was in the habit of thinking of the dowager as indefatigable. But then, of course, the elderly lady usually lived a fairly quiet life in the house on Berkeley Square. Jessica did not have the heart to say no. She had spent so much time with her grandfather in the last few days that she had almost neglected the lady who had been so kind to her since her arrival in town.

But truth to tell, she did not feel like being sociable to anyone. She wanted to be alone. She wanted to get away altogether. She could not remember ever feeling so miserable.

"Of course, your grace," she said. "I shall run to my room for my embroidery."

"Yes, do that, dear," the dowager said.

But Jessica was not to get much needlework done.

She had barely drawn her needle through her work when her companion began to speak.

"Now what is troubling you, my dear?" she asked. "Is it Charles again? I would guess it must be, judging from the look on his face and the look on yours at luncheon."

Jessica darted her a troubled look. "I have refused him again," she said.

"Oh dear," the dowager said. "I was afraid this would happen. Patience was never the dear boy's greatest virtue. I suppose he came thundering back with Heddingly, full of the conviction that as the granddaughter of a marquess you must marry him. What the dear boy would not have realized, of course, is that you have known of the connection all your life. It is a new idea only to him."

"Grandpapa shares the idea," Jessica said. "He gave Lord Rutherford his blessing."

"Yes." the dowager sighed. "He would. I remember wondering when Mirabel accepted his offer all those years ago just how she would manage such a very prickly character. She seemed to do quite well. But tell me, my dear, did you have to refuse?"

"Yes." Jessica threaded her needle through her embroidery and set it aside. She stopped even pretending to work at it. "Yes, I had to, your grace. I am sorry."

"You do not have to be sorry for me," her companion said. "After all, Jessica, you are the one who would have to live with the dear boy for the rest of his life. Forgive me for prying, but are you quite sure that you could not do it? It has always seemed to me that you have something of a tendre for Charles."

Jessica bit her lip. "I love him," she said so low that the dowager leaned forward somewhat in her chair. "But I could not live with him, no."

"His high-handed tactics have wounded your pride?" the old lady said.

"It is not just that," Jessica said. "I think if I did not love him I might be able to do it, ma'am. But how can I marry a man who offers for me only because it is the proper thing to do? I should feel all my life that I was a millstone around his neck."

"Gracious!" the dowager said. "The boy has never told you that that is his only reason, has he? What nonsense! He has been hankering after you ever since he first set eyes on you, m'dear."

"I know," Jessica said miserably. "Sometimes I think it would have been better if I had allowed him his will when I first knew him-pardon me, your grace. Then none of all this would have happened. He would have been satisfied. And perhaps I would have been too."

"What a very confused young lady you are, to be sure," the dowager said briskly. "I am not at all certain you understand the situation, my dear. But be that as it may, you have refused Charles again. I suppose he ripped up at you and said all sorts of rash things."

"It was a nasty interview," Jessica admitted. "Oh, ma'am, please, please help me. I must go away from here. I cannot stay, a guest of his family. I cannot face him every time I go beyond my room. Please help me."

"Poor dear." Her companion crossed the room and patted her on the shoulder. "You must remember that you are here on account of me and not on account of Charles at all. No one will think you are out of place here merely because you have refused him. But if you feel you must g

o, then of course you must. The marquess must take you back to London. Will he stay at Berkeley Square, do you think? Or will he insist on staying at a hotel?"

"No," Jessica said, shaking her head. "Grandpapa must not know I am leaving. Oh, please. He gave me a thundering scold when I went back to his room this morning and told me that I must reconsider. He will not even listen to any other idea. I cannot talk to him. I

know what he is like when he once gets an idea into his head. The same thing happened two years ago. Please, I cannot face Grandpapa again."

"Well," the dowager said, scratching her head and returning to her seat, "what are we to do with you, child? I shall have to take you back to London myself tomorrow. We shall resume our quiet life, Jessica, until the marquess comes to his senses. Or failing that, we will start making plans for the Season. I shall find you so many eligible suitors, m'dear, that your only trouble will be to choose among them."

"No," Jessica said. "You are most kind, ma'am, and I cannot begin to thank you for all you have done for me. But I cannot continue to be beholden to you. Do you not see? I must return to my old way of life if only I can. Can you help me, ma'am? Will you? Lord Rutherford was convinced when he sent me to you that you could and would. Please, can you find me a situation, and soon? I will be happy when my life settles to normal again. And I will no longer be a burden to you."

The dowager duchess viewed the distraught figure across from her and knew that the girl was not in any emotional state to listen to reason. Refusing Charles because she loved him indeed! And when Charles was so obviously head over ears in love with the gel, too. What disasters young people managed to make of their lives these days. Surely young ladies of her generation had had more sense.

"I suppose you want to go far away," she said. "I have a very dear friend in Yorkshire, my dear. Not far from Harrogate. She very likely will not have anything for you herself, but she will find something for you if I tell her that you come from me highly recommended."

"Oh, thank you, ma'am," Jessica said, her face brightening, "but will it not be too much to ask?"

"I took in her and her daughter for ten days four or five years ago. When they arrived in tow to find their house unready," the dowager said. "She has been looking for a way to repay me ever since. Now, I suppose you will want to be on your way as soon as possible. But not today, Jessica dear. You could, of course, travel to London this afternoon and set out on your journey tomorrow morning. But there would be too many questions asked here. And I do not suppose you would like your grandfather to come blustering after you before you could even leave town."

Jessica shook her head.

"What we will do," the dowager said, "is to order my carriage for very early tomorrow morning. Say five o'clock? Then you can go home, pack a trunk quickly, and be on your way long before anyone here has even realized you are gone. I shall send word that you are to travel in my best traveling carriage so that you will find the journey quite comfortable even if it is long and tedious. In the meantime, I shall also prepare a letter to send with you to Georgina."

"You are so kind." Jessica put her hands over her face. "I was really wondering at luncheon what I was to do with myself. I wanted to leave, but it just seemed too far to walk to London. You will explain to Grandpapa tomorrow? Poor Grandpapa. He has traveled all this way just to see me. But it will not work out, ma'am. We just cannot see eye to eye."

"You leave the marquess to me," the dowager said. "Now, dear, I need some advice on this new cushion cover I am about to embroider. Never did have much sense of color. Help me choose a pleasing combination. Come, we will move over to the window seat, where we will have daylight to help us."

The Duke of Middleburgh announced the betrothal of his younger daughter to Sir Godfrey Hall at the end of dinner that evening. Most of his listeners were surprised in the sense that they had not expected Lady Hope to give up her single state so late in life. But several were at least not shocked. Sir Godfrey's devotion had been detected by a few of the closer members of Lady Hope's family, and those members had also suspected that her feelings were engaged far more deeply than she herself realized.

There was probably not a person at table who was not delighted by the announcement. One had only to glance at the beaming face of Sir Godfrey and the glowing expression of Lady Hope to know that theirs was to be a love match. They sat next to each other, relieved that their efforts to keep the secret through luncheon, the long afternoon, and dinner could finally be relaxed.

Everyone was happy for them, even if everyone was not happy. The Marquess of Heddingly appeared cross and aloof, though he remained polite as befitted the guest of honor at someone else's table. The dowager duchess appeared somewhat preoccupied, though she did rally and look remarkably pleased when her son made his announcement. The Earl of Rutherford appeared to be totally out of spirits. Two young cousins seated close to him were quite unable to draw him into conversation during the meal. Yet his smile and congratulations to his friend and his sister were very obviously genuine. Jessica too found herself able to smile by making a concerted effort to forget her own misery and identify with the gladness and glowing happiness of her two friends.

Lord Rutherford had intended to disappear as soon as he could after dinner. The afternoon had been hard to live through though at least he had been able to choose activities that were unlikely to bring him into company with Jessica. The evening was a different matter. The family tended to stay close during the evenings.

In the event, though, he discovered that escape was not easy. When he sat beside Hope and Godfrey in the drawing room, he found them very unwilling to let him go again. And Godfrey must have enlightened his sister, Rutherford found. In the past she had scolded him several times for taking Jess away from possible tete-a-tetes with Godfrey. Now she almost immediately beckoned to Jess to join them. Rutherford drew in a deep and steadying breath and wondered how soon he could decently move away.

"My dear Miss Moore," Lady Hope called out even before Jessica had quite come up with the group, "you really must congratulate me again. I absolutely insist on it. Do come and sit down beside Charles and let me hear you tell Sir Godfrey what a very fortunate man he is."

The two men rose and Rutherford had no choice but to indicate the empty place on the love seat next to his own. Jessica seated herself without looking at him and proceeded to give her congratulations.

"I really have been very clever," Lady Hope said. "Sir Godfrey has been saying for a long while that he intends to travel to the countries of Europe now that it seems safe to do so. Well, my dear Miss Moore, I have very cleverly arranged matters so that I will be going too. After all, he will not be able to leave his new bride behind, will he?"

She smiled fondly at her betrothed.

"You will have to be as clever as I, Miss Moore," she continued. "You must find another gentleman who either has not been abroad at all yet or has ambitions of going again. There must be many such gentlemen. Charles for one."

She laughed at her own ingenuity and subtlety.

Lord Rutherford and Jessica sat woodenly side by side as if afraid that if they moved a muscle they would touch.

"We should all go skating tomorrow again," Lady Hope said. "It would never do, Miss Moore, if that one occasion was your last. You must try again so that next year you will find it very much easier. You were really doing quite famously with Charles."

"Somehow, I do not believe that skating is Miss Moore's favorite activity," Sir Godfrey said gently, laying a hand over Lady Hope's. "We should not press her, dear. Perhaps in a few days' time she will regain her courage."

"How quiet you are, Charles!" Lady Hope said. "Anyone would think you were not pleased for me, dear."

"Hope!" he said. "You know that is not true. I am more hapy than I can say, especially to know that you have had the good sense to choose Godfrey. It is just that you bounce with energy when you are excited about something. And you are very excited about this. Allow the rest of us to b

e more sedately happy, please."

"Oh, but I do not believe I can!" she said, jumping to her feet. "I think the occasion calls for dancing. We have not had any at all this year, though there are any number of persons here to make up couples and sets. We must dance this evening. Nothing else will do. I shall go and talk to Papa immediately about having the carpet rolled up. Cousin Edith will play the pianoforte. We will start with a waltz, and I shall absolutely want the four of us to begin it with perhaps Faith and Aubrey as well."

And she was gone, making her way past smiling cousins and uncles and aunts to her father. Sir Godfrey grinned at his two silent friends.

"I always knew that your sister was a bundle of energy, Charles," he said. "I now begin to wonder if I shall be able to keep up with her."

"If I see Hope striding along in a few years' time dragging behind her a pale shadow of a man," Rutherford said, "I shall know what has happened, Godfrey."

They both laughed, but truth to tell Rutherford was feeling far fromamused. He was feeling deuced uncomfortable and would quite cheerfully have throttled his sister at that moment. What was he to do about the silent figure beside him? He could not even plot how to move away from her. It seemed that they were doomed to waltz together as soon as Hope had organized the dancing. And that would not take long. All the people at one end of the long drawing room were already being herded out of the way so that a long line of footmen could roll up the Turkish carpet.

How could he dance with her? Touch her, look at her, speak to her?

"Will you mind dancing, Miss Moore?" Sir Godfrey was asking Jessica. "You really were not given much choice, were you?"

"I shall be delighted to dance for the occasion," she said. "And I am truly happy for you, sir. Lady Hope is a very special person."

It was fortunate that she was talking to Godfrey at that moment, Rutherford thought. When they were suddenly called upon to move from their places so that the footmen could clear their end of the room, it was quite natural for Godfrey to reach out a hand for hers. Rutherford stood slightly behind them for the next few minutes while they chatted amiably. He had not realized that those two were quite such friends. They joked and teased each other with great ease. He wished he could turn and leave the room.