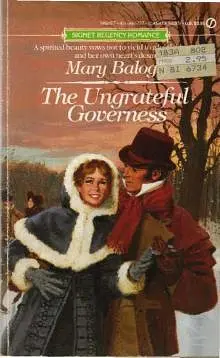

by Mary Balogh

Lord Rutherford drew breath to reply, but Sir Godfrey forestalled him.

"I do not doubt that Miss Moore would enjoy the outing," he said, "but I am sure that her grandfather would enjoy her company too. Let us leave them to each other and the warmth of the house, shall we, Lady Hope?"

Rutherford could almost have laughed at the expression on her face.

"Well, certainly, sir, if you really think it would be better to do so," she said. "We will be back before luncheon, anyway, and there will still be a great part of the day left, I suppose. If you would really prefer to stay yourself, sir, you must not feel obliged to accompany me, you know. I shall be quite happy with the children."

"Ah, but I wish to accompany you, Lady Hope," Sir Godfrey said, rising to his feet decisively and holding out a hand to help her.

Rutherford's lips twitched. It seemed entirely possible that there would be two family betrothals to celebrate that evening. If Godfrey could but convince Hope that he really wished to address himself to her and not to Jess, that was.

Lord Rutherford would probably have enjoyed listening to the conversation between his sister and his friend as they walked the two miles to the snow-covered hills to the south, surrounded by running and yelling children, two nurses and a governess, and two gardeners pulling along behind them a string of wooden sleds.

After various comments on the weather and the personalities of the children and young people around them, Lady Hope steered the conversation determinedly to Jessica. Sir Godfrey followed her lead with some amusement for a few minutes before drawing her to a halt and turning to face her.

"Lady Hope," he said, "may we put an end to this topic by agreeing that Miss Moore is indeed a beautiful and accomplished young lady who will make some fortunate man a good wife?"

She looked somewhat taken aback. "I beg your pardon, sir," she said. "I did not realize that I had embarrassed or offended you by talking about her."

"You have done neither, I assure you," he said, a twinkle in his eye. "But much as I esteem the young lady, I must admit to some boredom at finding her so frequently the topic of conversation between you and me."

"Oh," she said.

"Why do you not tell me about Lady Hope?" he asked, patting her hand on his arm and beginning to stroll onward again. "Have you finally recovered from your sad loss, my dear? And are you now ready to continue with the rest of your life?"

"Do you speak of Bevin?" she asked. "But that was long in the past, sir, and we were never officially betrothed, you know. I daresay Papa would not have easily given his consent, anyway. The matter was of no great significance."

"On the contrary, my dear," he said, "the passing of Lieutenant Harris has been very much the most significant event in your life. I have wondered many times if you would ever recover from it. You loved him very dearly, did you not?"

Her eyes looked suspiciously bright as she darted a glance and her nervous smile up at him. "Yes," she said. "Foolish, is it not, for a spinster of my age to have ever felt such emotion?"

"It is not foolish at all," he said gently. "I have found myself several times over the past several years almost envying the late lieutenant. And is not that foolish?"

For once Lady Hope seemed lost for words. She looked up at him, incomprehension in her face.

"I have waited for years," he said, "and am prepared to wait for as many more if I must. But I do feel the natural human need for hope, you know." He grinned. "And the pun was intentional. Rather clever, don't you think?"

She was still staring up at him. They had stopped walking again.

"Is there a chance, my dear," he asked, smiling almost apologetically down at her, "that if I remain patiently your friend for long enough, one day you will find yourself able to feel enough affection for me to put your safekeeping in my hands? I will never expect you to stop cherishing Lieutenant Harris in your memories."

"You have a tendre for Miss Moore," she said.

He shook his head.

"She is young and beautiful," she protested. "She would make you an admirable wife, Sir Godfrey. What would you want with an old spinster like me?"

He smiled. "I could answer that," he said, "but I would not wish to embarrass you, my dear. I have been your faithful admirer for years, Lady Hope. My life will be complete if the day ever dawns on which I may call you my wife."

Her eyes widened. "Me?" she said foolishly. "Me, sir? Your wife?"

He nodded.

"And I have always thought you so wonderful that I must find you an equally wonderful wife," she said.

He laughed and took both her hands in his. "That has been the only tiresome part of my association with you," he said, "though amusing too, I must admit. You have been making a particularly vicious siege on my heart with Miss Moore, though, have you not?"

"Oh, Miss Moore!" she said, pulling one hand away from his and covering her mouth with it. "She will be so disappointed."

"How flattering to think so," he said with a grin. "But it is not so, you know. Have you not noticed, my dear, that it is Charles and Miss Moore?"

"Charles?" she said, her eyes blank. "And Miss Moore?"

He nodded. "Is there any chance for me, my dear?" he asked.

She swallowed quite visibly. "I am two and thirty," she said.

"Are you?" he said. "I am relieved to say that I can still say the same. In two weeks' time I will have to add one number to the total."

"It may be too late for me to give you heirs," she said, her cheeks reddening to a deeper color than could be attributed to the cold.

"If I had to choose between a girl who would give me ten children and you with none, there would be no choice at all," he said. "It is you I love, my dear.

Besides, I see no reason for its being too late. And I believe that motherhood is an experience you really should have if you possibly can. You are wonderful with children."

"Everyone will laugh," she said, "at a woman of my age marrying and talking of having children."

"I believe everyone in your family will laugh with great delight," he said. "At least, I hope they will be delighted at your choice of me. I hope they will think me worthy. And we can keep secret our plan to have children, if you so choose."

"Aunt Hope. Aunt Hope." They were both suddenly distracted by the row of children standing at the bottom of the distant hill, all chanting in unison.

Lady Hope beamed at them and waved her hand vigorously. "Coming, children," she called.

But Sir Godfrey caught at her hands again before she could move. "Is the answer yes?" he asked. "Or is there at least a chance that if I wait longer…?"

Her hands suddenly squeezed his with quite unladylike force. "I am so glad we are going sledding," she said. "I would not know else how to contain my emotions, sir. Of course, I will marry you if you are quite, quite sure that you really wish to marry me. I have always envied the young lady who would eventually capture your heart. And you need not fear that I will still harbor a love for Bevin. I did love him dearly, and of course I shall always treasure his memory. But a dead love cannot sustain one through life, sir. It has been a full year or perhaps more since my heart has felt empty again. And I have been afraid to put you there in his place, for really I never did dream that you would ever wish to be there."

"For the rest of my life, if you please, Hope, my dear," he said, "as you will surely be in mine." He brushed the backs of his fingers lightly across her cheek and smiled down at her.

"Aunt Hope. Aunt Hope. Aunt Hope." The chanting became unrelenting.

"Coming!" she called back, beaming ahead of her and reaching for Sir Godfrey's arm. "They will not be content for us to merely push them from the top, you know. We will have to ride. And we must fall off at least once, preferably in the part where the snow is thickest. They will be most disappointed if we fail to do so."

Sir Godfrey smiled fondly down at her beaming face. "What a very kind lady I am going to have as a wife," he said. And then into her ear as they drew

closer to the children, who were dragging the sleds uphill, having seen that she was coming at last, "I love you."

"Oh," she said, looking up at him with sparkling, excited eyes before gathering her fur-lined cape in her hands and hastening up the hill in the wake of the children.

Jessica had hoped that she would not have to venture downstairs at all during the morning. Her grandfather was tired after all the traveling he had done before Christmas and after the excitement of the day before. She had persuaded him to keep to his rooms until luncheon. What was more natural in the world than for her to stay with him?

For the rest of the day she hoped to be able to stay very near him or the dowager duchess or Lady Hope or anyone safe. She must not, whatever she did, put herself in the position where Lord Rutherford could have a private word with her. She found it difficult to believe that he really did intend renewing his offer for her. Yet her grandfather said it was true. But she was not going to give the earl a chance to do any such thing, she had decided.

Yet even before luncheon it was impossible for Jessica to put her resolve into effect. Her grandfather wished to know if a certain book was kept in the duke's library. Nothing else would do. Jessica suggested the titles of several books she had in her room, but quite in vain. She must go downstairs and see if that one volume was there.

How could she say no? she thought in some despair as she crept stealthily down the staircase, first past the floor on which most of the living apartments were situated and on down to the hall and the library. Even though she was convinced that Grandpapa would be asleep again before she returned to his room, she could not have denied his request.

She drew a sigh of relief as a footman opened the door into the library for her and she discovered that it was empty. And although the door to the morning room had been open and a hum of voices coming from inside, she did not believe that she had been spotted. If she could just find the book quickly and be as fortunate on her way back upstairs!

Jessica knew, even as she descended the library ladder, the book she wanted clasped in her hand, that she was not to be that fortunate. Her back was to the door when it opened. The person entering could have been any one of a dozen or more people. But she knew without turning just who it was. And she knew by the way the door closed quietly but firmly behind him that he had seen her come in and had come deliberately to talk to her. She drew a deep breath and returned both feet to the floor.

"Good morning, Jess," the Earl of Rutherford said.

"Good morning, my lord," she said, turning and smiling brightly-too brightly, she thought immediately with some annoyance. She held up the book. "I am on an errand for Grandpapa." She moved purposefully toward him and the door.

"Let him wait for it a while," he said, smiling at her and taking the book from her suddenly nerveless fingers when she was close enough. "May I talk to you, Jess?"

"Grandpapa is waiting," she said. "He has nothing else with which to occupy his time."

"Stay and talk with me, Jess," he said.

If he just would not smile! she thought. A smile did wonders for his face. It did not make it exactly more handsome, but it made him look kindly and far more human. She preferred his arrogant look. It was easier to withstand. She said nothing.

"I made a mess of things rather the last time I talked to you about marriage," he said. "I am hoping I can do somewhat better this time."

"Oh, no!" Jessica put both hands up defensively before her. "Please say no more, my lord. I told you on that occasion that I have no wish to marry you. Nothing has changed since then."

"But why not?" he asked. "What is the problem, Jess?"

She was shaking her head. "We would not suit," she said. "You are not the sort of man with whom I would feel comfortable. I… I cannot accept, my lord."

He frowned. "What have I done that is so dreadful in your sight?" he asked. "From the first I have shown a preference for you. I have never forced you into anything against your will. I offered you marriage even before I knew who you were, so you cannot accuse me of snobbery. I know you are not averse to my person."

"That is unimportant," she said. "There are many qualities one looks for in a husband beyond that."

"And you can find nothing else in me to esteem, Jess?" he asked.

She shook her head but said nothing. She was gazing at him almost imploringly.

"Am I so lacking in all admirable qualities?" he said harshly. "I had not thought myself quite so depraved. Perhaps your standards are just too high, madam."

"Perhaps they are," she said very quietly.

He looked at her in exasperation for a few silent moments. "You realize that it makes no difference whatsoever, don't you?" he asked. "You must marry me whether you admire me or not. Perhaps it is fortunate that at least my caresses please you, Jess."

"I will not marry you," she said calmly.

He laughed unpleasantly. "You did not hear me," he said. "You have no choice, my dear, any more than I have. Do you think I enjoy the thought of marrying a woman who despises me, who cannot see one trace of goodness in me? And a woman, moreover, who has deceived me and thereby trapped me into having to marry her? Oh, I know you did not deliberately do that, Jess, but you did it nonetheless."

"You need not fear," she said, her voice flat. "I will not marry you."

Two very heavy hands clamped onto her shoulders suddenly, and she found herself looking into two very intense blue eyes. "You are still a virgin," he said, "but do you realize by what narrow a margin, my girl? You and I have done together everything else that a husband does with his wife except that and indeed a great deal more than a wife of any great sensibility would ever dream of doing. You have lain in bed with me, Jess. Your body holds only one secret from me. In this society that you have shown some eagerness to be a part of young ladies do not offer even their lips to a man unless they are prepared to marry him. You have been compromised, Jess. Hopelessly and irretrievably compromised. You must marry me."

"I will not marry you," she said. Her breath was coming fast, but she looked steadfastly back into his eyes. She would not cringe before him.

He shook her roughly before releasing her and turning his back on her. "There are certain things that one does, whether one likes them or not," he said. "Marrying a lady one has compromised is one of them. It seems you have been shut away from proper behavior for too long to know what is what, Jess. Marry me you must. You will find that your grandfather will be as adamant as I. I shall discuss the matter further with him. I am more likely to get satisfactory results."

"Do so," she said. "Perhaps you would also like to marry my grandfather. It might be a more satisfactory marriage."

He spun around again, his face such a mask of fury that Jessica took an involuntary step backward. His hands opened and closed into fists at his side.

"By God, Jess," he said, "you had better learn to curb your tongue before we are wed. I am very like to strike you if you speak to me in that way ever again, and then you will have yet another evil aspect of ray character to throw in my teeth. I have tried to be pleasant to you. I have tried to make a friend of you. I have tried to show you in the last few days that marriage to me will not be such a bad bargain after all. It seems you are determined to cast me in the role of villain. But it would be in your own interests to try to alter your vision, my dear. I would imagine it is a dreadful thing indeed to hate one's husband. And I will be your husband."

"Fortunately, my lord," she said with as much calm as she could muster, "I live in England, where one may expect to have one's freedom upheld in a court of law, and I am of age. I will not be married merely because I have a desirable body or merely because I have transgressed a rule of a society that I have lived without all my life. I am a person, Lord Rutherford, and when I marry-if I marry-it will be to a man who believes that he cannot live a complete life without that person-all of it. All of me. Call me a hopeless romantic if you wish. Yes, that is what I am. I will not marry because I must. I will marry

only when I will."

He was staring at her with wide-open eyes, the harsh, arrogant look completely gone. Jessica picked up the book very deliberately from the table where he had laid it, stepped past him, and left the room. When she turned to shut the door quietly behind her, it was to find that he had not moved.

14

Lord Rutherford stood for a long time in the same spot after Jessica had left the library, his eyes closed, his hands clenched loosely at his sides. She would not marry a man who wanted her for her physical attractions merely, she had said, or one who offered only because she had broken society's rules. She would marry only the man who could assure her that he wanted all of her, her whole person. She would marry only a man who loved her.

Had he failed, could he possibly have failed to show her that he was such a man? Could he possibly have given the impression that he wanted her only for one of the first two reasons? Surely not. He loved her so very deeply, had been so obsessed by his need of her for weeks, that surely he must have made that fact obvious to her. She could not have failed to understand. She had rejected him because she did not want him, did not love him, not because she misunderstood. Surely.

Had he told her that he loved her? Lord Rutherford cast his mind back over his confused memories of their interview. No, he had not used that exact word. He could be almost sure of that. It was not a word he was accustomed to using. He would be self-conscious using it. He would certainly remember if he had told her that he loved her.

What had he said, then? He must have said something that would have conveyed the same message to her. He recalled admitting to her that he had made a mess of the last proposal. That was when he had planned to tell her that at that time he had still been largely unaware himself of the fact that his whole happiness depended upon her accepting his hand. That was when he was to have told her how much he had come to esteem her, how much he longed to get to know her fully. That was when he might have told her he loved her if he could have summoned the courage to use that exact word.