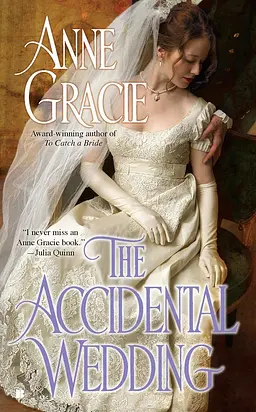

by Anne Gracie

“It . . . won’t,” he managed to say, and then he was naked and she was kissing him, and he was kissing her and pushing up the hem of her nightgown with one hand, smoothing up those long, slender silken thighs toward the hot, moist welcome of her center.

“My nightgown,” she muttered feverishly and struggled to pull it off, but it was buttoned to the neck.

He cursed silently, caressing her intimately with one hand while he tried to undo dozens of stupid little buttons with the other hand. It was going to take forever to get the blasted thing off her and he couldn’t wait that long. With a muttered curse and a “sorry about this,” he grabbed the neckline of her nightgown in both hands and in one movement ripped it open from neck to hem. And stared, struck afresh by the naked, creamy beauty of her.

Seeing his expression, her eyes grew darker, half closed and sultry like a sleepy cat. She stroked his body in slow, sensual appreciation, rubbing herself against him, openly glorying in the sensation of touching him. He felt like a king, a god, all powerful and . . . about to explode.

He lowered his face to her breasts and caressed them with lips, tongue, and jaw, all the while stroking her between the legs, feeling her readiness, her eagerness. She arched and writhed beneath him. He couldn’t wait much longer. He positioned himself between her thighs and she responded by wrapping her legs around him tightly, urging him on.

He entered her in one slow, smooth stroke, once . . . twice . . . and the rhythm took him, driving all thought from his brain. He battled to delay his climax as long as possible, but it was too late, too late . . . until she arched and screamed and shuddered uncontrollably, shattering around him as he shattered within her . . .

When Maddy woke, the sun was up and Nash was gone. The only evidence of his visit in the night was the tenderness between her legs and the ruined night gown. And the dent on the pillow beside her.

She turned over, snuggled her cheek into it, and relived their lovemaking from the night before. It was better than a morning dream, any day.

She stretched luxuriously and tried to tamp down the happy, fizzing feeling in her blood.

Don’t mistake what passed between us for love . . . It’s just how it is between a man and a woman . . . A healthy expression of desire.

Perhaps it was. She was new to lovemaking and the effects of desire, but one thing was very clear in her mind: she loved Nash Renfrew with all her heart. And if desire was all he could offer her, then she would take it gladly, for to be the object of his desire was . . . utterly splendiferous . . .

“How are you finding life as a maid, Lizzie?” Maddy asked as Lizzie brushed out the tangles in her hair later that morning.

“A bit different from what I expected, miss, but still better’n milking cows any day.”

“In what way different?”

Lizzie pulled a face and began to braid Maddy’s hair in a coronet around her head. “Belowstairs they’re that starchy and hoity-toity, you wouldn’t believe, miss. I sat in the cook’s chair yesterday—just for a minute, I mean she wasn’t using it or anything—but you would’ve thought I’d spat on the floor, the way everyone reacted.” She put on a starchy voice, “‘Maidservants sit at that end of the table, Brown; this end is reserved for the more important members of the household.’ ” Lizzie pulled a face and winked. “Cows, wherever I go.”

“They’re not unkind, are they?”

“Oh, no, miss, don’t you worry. Old Mrs. Deane, she’s a darlin’. And Cooper, that’s Lady Nell’s maid, she reckons it’s worse in other big houses, believe it or not.”

Cooper had been the maid who’d brought Maddy the beautiful cashmere shawl on the first night. “I thought she looked nice,” Maddy said.

“She is. She’s been showin’ me the ropes. Said Lady Nell took a chance on her like you’re takin’ on me. And Mr. Benson, the butler, is a good sort. He likes everything just so and is a demon for hard work and treats us all like we’re in the army, but for all that, he ain’t no snob and he don’t mind a joke. It’s the ones who’ve been in service all their lives I can’t stand. They act as though they’ve swallowed a poker and look at me like I’m something they stepped in.”

Maddy laughed. Lizzie was far too outspoken and down-to-earth for a maidservant, but Maddy loved her for it. She could understand, however, that the girl would raise some hackles in the formally trained ranks belowstairs. “I’m so glad you came with me, Lizzie. But if anyone does mistreat you, you must come to me at once.”

Lizzie snorted. “Nah, I can handle meself, miss.” She frowned critically in the mirror. “Hair’s always difficult after it’s washed, ain’t it?” She used a hot iron carefully and turned a few escaping wisps into tiny ringlets. “There, that’s better. Suits you lovely, it does, miss. Mr. Renfrew will be dazzled all over again.”

“Dazzled?” It was a lovely thought. Unlikely, but lovely.

Lizzie laughed. “Haven’t you noticed, miss? Whenever he claps eyes on you, he can’t seem to look at anything else. The poor man doesn’t know whether he’s comin’ or goin’. Just like my Reuben was.” She turned away and added in a slightly husky voice, “So keep on dazzlin’ him, miss, and don’t let him run off on you.”

She would try, Maddy thought, but as poor Lizzie had learned the hard way, you couldn’t make someone love you. It happened or it didn’t.

Briskly Lizzie began to tidy the room. “Now, you’d better get on, else there’ll be nothing left for breakfast. I could smell bacon cooking when I went past the kitchen. Lovely, it was. Oh, and Lady Nell said to tell you someone’s coming at ten to measure up the children for new clothes.”

“That’s a sight I haven’t seen before,” Nash commented from the library door. “You sitting down, peacefully reading.”

Maddy jumped and put down her book. It was their second day at Firmin Court and the children had settled in well, so well in fact that Maddy had some time to herself for a change. “I did offer to help—I’m sure there is any amount of work to be done, but Nell told me I was a guest and should do whatever I pleased.” She sounded a bit guilty.

“Quite right,” he said approvingly. “I haven’t seen you take time for your own pleasure in all the time I’ve known you. What’s the book?” He picked it up and frowned. “Russia?”

“It’s a little out of date, but very interesting. Did you know that—”

“Don’t bother with it.” He closed it with a snap and put it aside.

“But I’m interested—”

“Other possibilities have arisen.”

She looked up at him, puzzled. “What possibilities? Do you mean we’re not going to Russia in June?”

“I don’t know, yet. It doesn’t matter.” Nash made an impatient gesture. He really didn’t want to discuss this now. “I bring a message from Jane and Nell that you’re to come at once.”

She rose, anxiously. “Is something wrong?”

“No, but you must come. Now.” He caught her by the hand and led her from the house.

“But this is the way to the stables,” she said after a moment. “I thought you said Jane wanted me.”

“She does. We’re going behind the stables. The boys are in the stables, mucking out stalls, filling water troughs, cleaning tack, and working like navvies. Apparently they consider this seventh heaven.”

She laughed and gave a little skip. “That’s because Harry exchanges work for riding lessons.”

Nash nodded. He knew all about it. He was the one giving the lessons. “I’m surprised they haven’t learned to ride before this.”

“John had a few lessons, but after Papa fell from one and broke his back while hunting, there was no question of any of us riding—all the horses were sold.”

He squeezed her hand. “For someone who’s seen so much death, you’re a cheerful soul, aren’t you?”

She gave a philosophical smile. “Grand-mère lost almost everyone she ever loved in the Terror, but she taught me to make the most of life while I can. Papa died t

wo years ago, and I did mourn him for a year, but out of respect more than anything. We were never close. Besides, you can’t stay gloomy when there are young children to take care of.”

“I suppose not, especially with your lively five.”

“And, of course, finding Papa had left only debts was another distraction.”

He gave a snort of laughter. “I suppose you could call it a distraction.” Survival was what she meant. He glanced down at her with a smile. A living example of everyday courage, his bride.

“I looked your father up in an old copy of Debrett’s,” he told her. “Sir John Woodford?” She nodded. He continued, “It listed an estate. I gather it was sold.”

She shook her head. “It’s entailed—the estate goes to John when he turns one and twenty. Mr. Hulme has rented it out to tenants for a very good sum.”

“Hulme? The old goat you were going to marry?”

She nodded. “He’s John’s trustee. He was Papa’s lifelong friend and neighbor and undertook to restore the estate to profitability by the time of John’s majority. Finance is his passion.”

It wasn’t his only passion, Nash thought darkly. “Why didn’t your father leave the children in his charge, rather than burden a young, single woman?”

“I suppose Papa thought the children were better off with a woman, and finances were more suited to a man. Besides, Papa wanted me to marry Mr. Hulme, too.”

Nash stopped dead. “So when you refused, this Hulme fellow turned you out of the family home and didn’t even provide you with a house?”

She avoided his gaze. “I know some would say it was selfish of me, to put my own desires before the welfare of the children—”

“Nonsense! You did the right thing.”

“Well, I think so, too,” she said frankly. “Mr. Hulme wanted to send the boys and Jane away to school and once I married him I’d have no say in the matter. But they’d just lost their parents and their home. They didn’t need to be sent away to live with strangers. So I wrote to a friend of Grand-mère’s—your uncle—and he offered me the cottage.” She tugged on his arm. “Come on, I don’t want to keep Nell waiting. I think I can guess what I’m going to see,” she told him.

“Oh?” He glanced down at her.

“It appears Jane has always had a burning, though secret ambition to be a horsewoman.” She slanted a mischievous look up at him. “Am I close?”

“My lips are sealed.”

“I thought so. I’m very glad. Papa didn’t approve of ladies riding: he said it was unfeminine and dangerous. But I saw Jane watching Lady Nell ride yesterday—she’s a very accomplished horsewoman, isn’t she?”

“Best seat in the county,” Nash confirmed.

“And this morning Jane found one of Nell’s girlhood riding habits in an old trunk in the nursery. It had a couple of rips in it but Jane—my Jane, who has to be forced to take up a needle—happily sewed them up without a word of complaint! And all day she’s been whispering to Nell in corners and disappearing on mysterious errands. She’s determined to outdo the boys, of course.”

He laughed. “My money’s on Jane.”

They turned down the pathway that skirted the stables. Early roses were coming into bloom all along the south-facing wall, soaking up the warmth of the sun. The rich rose scent surrounded them and she hugged his arm unselfconsciously. There was a spring in her step he’d never seen before.

She was born for this life, he thought suddenly. A country house filled with children. How could he drag her off to foreign lands and a life of careful diplomacy?

“You like it here, don’t you?”

She glanced up with a smile, her eyes shining. “It’s wonderful. Everyone is so kind and the children are happy and excited and busy and . . .” She let go his arm, plucked a rose, and twirled around. “I feel suddenly free . . . and young and alive.”

“You are young and alive.” And sweet and lissome and utterly irresistible. He caught her twirling body in his arms and swung her off her feet. They twirled together, until, dizzy, he staggered sideways and collapsed against the wall, Maddy clasped to his chest, laughing and breathless.

“But you’re not—” He broke off, shocked by what he’d been about to say.

“Not what?” She laughed up at him. “A fool in—”

He stopped whatever it was she’d been about to say by covering her mouth with his in a swift, firm kiss. Then he set her abruptly on her feet, suddenly chastened, almost serious.

In silence they walked on. Nash couldn’t believe what he’d been about to say to her. But you’re not free—you’re mine. Claiming her. Claiming her, what’s more, on a surge of possessive lust. Jealously.

He stared blindly ahead as he strode along the path, seeing in his head his mother twirling coquettishly, laughing, teasing, tormenting . . .

It was in the rose garden at Alverleigh. Nash was . . . eight? Nine? Children weren’t allowed in the rose garden, but he’d hit a cricket ball over the hedge and had sneaked in to fetch it. He’d found his parents strolling among the roses. Fearful of being caught there, he’d hidden. And watched.

Father was picking roses and giving them to Mama, who pulled them slowly to pieces, one by one, tossing the petals at Father’s head, and laughing as he brushed them from his hair.

Father picked off the thorns, but he must have missed one, because Mama’s hand got scratched and she exclaimed, and held it out reproachfully to Father. Nash could see the thin line of blood on her palm.

Father had taken her hand and licked off the blood, carefully, licking up her arm. Then he’d growled like an animal and snatched her up against his chest—just as Nash had done with Maddy—and carried Mama into the house. They were laughing and murmuring and left a trail of rose petals behind them.

But later that day Mama’s bags stood in the hall and they were screaming at each other, Mama white and tense and brittle, and Father so enraged his face was dark red and mottled and terrifying.

Nash and Marcus had watched from behind the rails of the staircase, quiet as mice, knowing they’d be beaten if they were caught eavesdropping. Nash wanted to do something to make them stop. Marcus said no, nothing could. It was always like this when Mama came home. She hated the country.

But Nash wouldn’t listen. He knew how to make Mama happy again, make them both happy, and stop the terrible screaming. Taking the hidden servants’ stairs, he ran out to the rose garden and plucked a dozen roses.

He even picked off all the thorns, like Father had, so Mama wouldn’t scratch her fingers. His hands got all scratched and bloody himself but he didn’t care. As long as Mama stayed . . .

He still remembered how hard his little heart beat as he stood in the hallway, holding out the roses to his mother, so determined to make her happy again.

He’d never forget the silence as the yelling suddenly stopped, the shocking silence that somehow pressed on him like a physical weight.

And the terror as his father turned on him with a hiss of rage.

He wanted to run, but he couldn’t move, couldn’t speak. He just squeezed his eyes shut and held out the roses to Mama. His hands shook. And Mama laughed.

Father dashed the flowers from his hands and flung him from the room, halfway across the hall . . .

Mama left for London shortly afterward.

Father stayed long enough to give Nash a severe beating for interrupting his parents’ conversation and for stealing the roses. And then he’d beaten Marcus for not stopping Nash—he was the eldest, Nash’s behavior was his responsibility.

And then Father had left to follow Mama back to London. He couldn’t live without her; they loved each other too much, the servants murmured when they thought the boys weren’t listening.

Nash learned that day: this was what happened if you loved someone too much.

As an adult he’d seen it ruin other people’s lives: marriages and families torn apart for what they called love, for a passion that could not be denied.

There was no longer a rose garden at Alverleigh. When Mama had died, Father had ordered all the roses ripped out of the earth and burned, the bowers and archways torn down, the garden put to the plough. Now only a sward of smooth green lawn remained where roses had once bloomed.

Nash glanced sideways at the lovely young woman hurrying along beside him, her hand tucked into the crook of his arm, skipping every second or third step, as carefree as a young girl.

She would stay that way, he vowed.

Nash would not be jealous and possessive and tormented by love. He would have a civilized marriage, one where nobody got hurt and where children would not have to watch, agonized and helpless, consumed by fear.

A marriage of mutual respect and esteem, not passion.

All that was required was the necessary self-control.

Twenty-one

On their third afternoon at Firmin Court, the peace of Maddy’s existence was shattered by the arrival of three more guests. First the Earl of Alverleigh and Lord Ripton arrived, riding neck and neck down the driveway, scattering gravel as they thundered toward the front steps. Maddy thought the horses would leap up the steps, but at the last second, they drew up, Luke announcing that he’d won by a nose.

“Dashed fine bit of blood, that, Marcus,” he commented as he tossed the reins to a waiting groom. “Didn’t know earls could ride.”

“Didn’t know barons were lunatics,” Marcus retorted coolly. He glanced at Harry and Nash, who’d come out to welcome the new arrivals. “He’s quite insane.”

They both nodded. “Yes, but only when it comes to racing,” Harry said. “He and Rafe egg each other on. I’m surprised you did, though.” He eyed his half brother narrowly.

“He’s almost as good a rider as Rafe,” Luke admitted reluctantly.

“I’m better than Rafe,” Marcus said coolly.