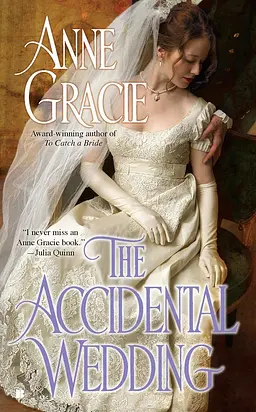

by Anne Gracie

He rummaged through the box where she kept her clothes and pulled out a clean nightgown and a woolen shawl. He shook the nightgown out and warmed it at the fire, grimly noting the number of places it had been patched. She’d finished the toddy and was sitting half curled in the chair, her eyes closed.

Swiftly he undid the fastenings of her cloak. No wonder she was cold, the damned thing was almost threadbare. He pushed the cloak off her shoulders, then began to undo the tiny buttons down the front of her nightgown.

Her eyes flew open. “Wha-what are you doing?”

“Your clothes are wet. You need to change.”

“Don’t.” She pushed his hands away.

“Very well, you do it.” He stood back and waited, telling himself it was better if she did it anyway. Her nipples were hard berries beneath the soft, well-worn fabric. Cold, not desire, he told himself savagely. He handed her the warm, dry nightgown and the shawl, stepped away, and turned his back.

Behind him, fabric rustled. He gritted his teeth, imagining her slipping the damp nightgown over her head, leaving her naked curves bathed in firelight. From the corner of his eye he saw the muddy-hemmed nightgown hit the floor. It took every shred of willpower he had not to turn around, not to take her in his arms, carry her to the bed, and warm her in the most elemental fashion of all.

What had possessed him to make that blasted promise?

It seemed an age before she said, “You can turn around now.” He turned slowly, half hoping she’d decided to live up to his imaginary view of her and greet him wearing nothing but firelight, but she was buttoned to the chin and wrapped in the shawl.

“You’re still wearing those slippers, dammit.”

She frowned. “I forgot. I can hardly feel my feet, they’re so cold.”

Muttering under his breath, he grabbed a towel, knelt, pulled her slippers off, and dried her feet carefully. They were icy to the touch. He chafed them gently in his hands and she moaned, with pleasure or pain, he wasn’t sure.

“The children slept right through it all,” she said in a wondering voice. “So much destruction and they slept right through it. He was so quiet this time.”

“That’s something to be grateful for, then, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it would have been dreadful if they’d seen the bees burning. So distressing . . . And Jane and Susan would fret about the hens and want to go out and make sure they were safe—you will check them later, won’t you?” She didn’t wait for him to reply. “The boys will be so upset, they’ve worked so hard in the garden. And Lucy—oh dear, Lucy loved the bees. She used to tell them s-stories.” She bit her lip and fell silent. He could tell she was fighting tears.

He fought the urge to haul her into his arms and kiss the tears away.

He rubbed and kneaded her feet until they were warm and rosy and she was arching against his hands in pleasure—and this time he was sure.

“Bed.” His voice came out hoarse.

She didn’t move. He glanced at the expanse of stone flags between herself and the bed and didn’t blame her; her feet would be cold again by the time she got there.

Unable to help himself, he bent and scooped her off the chair.

She started. “What are you doing? Your ankle!”

“Seems to have recovered.” He was limping, but that was because of his ruined boot and the shuffling gait it required. His ankle ached, but not unbearably. “Must have been a sprain after all.”

He carried her to the bed and slid her between the sheets. She pulled the bedcovers around her and curled up on her side like a little girl. “You’ve been very kind—” she began but he didn’t wait to hear.

He stomped away, back to the hearth. Kind! He didn’t want to be kind. He wanted to slide into that bed with her and take her, strip that blasted patched nightgown from her, and take possession of her, learning her inch by inch, driving every thought, every fear from her brain, drowning her in sensation. He wanted her arching against him, the way her feet had arched against his hands, moaning with pleasure. He wanted to taste her, to know her, to bury himself deep within her and to feel her shudder and cry out as he brought her to ecstasy. The gift of oblivion.

His body shuddered uncontrollably at the mere thought. He was rock hard and ready. And she was warm and pliant.

And vulnerable.

He grabbed the tongs and pulled the two hot bricks from the hearth. He wrapped them in rags until they were easy to handle, then brought them to the bed.

Her eyes were closed. She looked exhausted. He lifted the bedclothes and slid the hot bricks in, locating her feet and settling a brick at each foot. She sighed in contentment and her feet curled around them.

She didn’t need him, he told himself savagely: a hot brick would do just as well.

As for himself, he had a cold, stone floor and that was all he needed. He dragged off his good boot and kicked off the other, removed his breeches, and climbed into the roll of bedding by the hearth. He tossed and turned. Could a floor be any colder or harder? At least the fire threw out some heat and he was marginally warmer on that side.

Jane and Susan would be fretting about the hens . . . You will check them later, won’t you?

Cursing, he untangled himself from the bedclothes, pulled on his breeches and boots, and stomped outside to check on the blasted hens. Why did he make so many stupid, damned inconvenient promises?

It took Nash forever to get to sleep again. Never had he kissed a woman so briefly, not a woman he wanted. And he wanted Maddy Woodford; his body thrummed insistently, his blood singing and alive and wanting.

That moment when her lips had parted slightly, softly under his . . . The sweet, elusive taste of her, just like her scent. What he wouldn’t give to taste her properly . . .

He groaned and turned over on the stone floor, wishing its coldness would pull the heat from him, but it was a different kind of heat keeping him awake.

Resolutely, he turned his mind to the problem at hand. Who was this evil bastard who came in the night? Who might have it in for Maddy and the children so badly he would destroy their livelihood? They wouldn’t starve—Nash would see to that—but this swine wasn’t to know that.

Somebody wanted her out of the cottage and was obviously prepared to commit wanton destruction to do it. And yet, there had been no attempt to hurt Maddy and the children.

Five “Bloody Abbot” visits in a few weeks and, apart from frightening a woman and children, burning beehives and destroying plants was the worst he’d done.

He fell asleep eventually, his mind full of questions, his body tense and edgy with desire.

Nash woke shortly after dawn to the click of a quietly closing door. He threw off the covers, grabbed his pistol, flung open the door, and nearly tripped over Maddy sitting on the front step, tying the laces on her big ugly work boots.

“What? What is it?” he demanded, scanning the horizon.

“Nothing.” She stood, neatly dressed in her faded blue dress, her hair gleaming wine-bright in the morning sun and coiled into her usual neat knot. She looked lovelier than any woman should after a disturbed night and very little sleep.

Her gaze moved from his face to his hair, then down to his toes and back. “Good morning. I assume you slept poorly.” Her eyes danced.

He stiffened, realizing he probably looked rather less dapper than he preferred to look in front of women he desired, in bare feet and wearing a nightshirt made for a short, rotund vicar. He raised a casual hand to his hair and found it standing in spikes. He tried to smooth it inconspicuously.

“What are you doing up at such an hour?” He sounded, even to his own ears, gruff and surly.

“I need to see to the hens.”

“I shut them in after you went to bed.”

“I know. I heard you go out again last night. Thank you.” She started down the pathway.

“Wait,” he said. “I’ll dress and go with you.”

“It’s all right,” she told him. “There’s no

thing you can do. I want to check on the damage before the children are up.”

“I’m coming,” he told her firmly, and went inside to pull on his breeches, boots, and coat. He made his ruined boot almost wearable by the simple expedient of tying it on with strips of rag. It looked utterly ridiculous, but he had no choice.

He found her on her knees in the vegetable garden, replanting any plants that hadn’t been totally destroyed, and throwing the ruined ones into two piles: usable as food and only fit for the hens. She looked almost serene.

“I thought you’d still be upset after last night.”

She sat back on her heels and wiped a strand of hair from her eyes with the back of her hand, leaving a stripe of dirt in its wake. “Upset? I’m more than upset, I’m furious. But I won’t let that monster defeat me. It’ll take a lot of work to get the garden back in shape, but at least this is the beginning of the growing season and not the end.”

“Get the garden back in shape? You mean you’re going to start again?” He looked at the mess that had been her garden. It was a huge amount of work.

She snorted. “What should I do? Give in, tuck my tail between my legs, and run back to Fyf—run away?” she amended. “No, no, and no! I will not be driven from my home by a coward who frightens children. Besides, I have the perfect solution to deal with him in future—geese.”

“Geese?” How would more poultry solve her problem?

“Geese make excellent watchdogs. You should hear the fuss they make when any stranger is around—and they eat grass and grain, which is cheaper than feeding a dog,” she finished triumphantly. “I cannot imagine why I didn’t think of them sooner. Geese would honk a warning of any spineless creature creeping in the night to terrify children and burn innocent, hard-working little bees! That reminds me . . .” She glanced past him to where the bee hives had stood in their stone shelters. “I’d better clear the wreckage of the hives away. I want to clean up as much of the damage as I can before the children see it.” Seizing a spade, she headed for the hives.

“I’ll help, just tell me what to do.” He’d never pulled a weed or tended a garden in his life but his muscles were at her disposal.

“Thank you.” She gave him a dazzling smile that drove every thought from his mind. “Bring the wheelbarrow, please.”

He fetched it, a big old clumsy thing that was hard to balance and harder to steer. As it wobbled toward the hives, she looked up and tossed him a quick grin. “That’s what I used to bring you inside the house, after your accident.”

“This?” He was shocked. “You carried me on this? How?”

She shrugged. “I didn’t say it was easy. But needs must.”

Needs must indeed. Nash was stunned, faced with the very physical evidence of what she must have done to save his life. Up until now it had been an academic exercise; he hadn’t considered the logistics of how she’d managed to transfer his insensible body from the muddy ground, inside, and into her own bed.

He stared at the small, slender frame, currently scooping a mess of burned straw and honey into the barrow lined with fresh straw. How the hell had she managed to lift him?

“It wasn’t easy,” she admitted when he asked. She explained how she’d tied him to the wheelbarrow and he was dumbfounded.

She handed him a spade. “Can you dig a hole over there, please? I’m going to bury the hives.”

Dig her a hole? He’d dig her a dozen.

By the time the children woke and came looking for their breakfast, Maddy and Nash had cleared away most of the ruined plants. The stone alcoves where the hives had stood were cleaned out, stained with ash and still a bit sticky, but empty.

The blackened mess of hives had been tossed into a hole, but Maddy stopped Nash from covering it with soil. “We will have a ceremony,” she told him. “The children will want to say good-bye.”

The children wandered through the garden, exclaiming distressfully over the vandalism, but they took their cue from their older sister and started repairing trellises and replanting seedlings almost immediately. The girls counted the hens—all present and correct—and collected the eggs as usual, white-faced and shocked.

Maddy gave them time to absorb the destruction, then fed them a big breakfast of porridge with cream and honey, followed by a toast and honey for those who still had space.

After that they held a small simple ceremony for the bees. Nash had never attended a funeral for any animal, let alone bees.

Each child brought a flower of the sort that bees were known to like. They lined the grave. Maddy said a few words. “Dear bees, we’re so sorry for the evil thing that was done to you. Thank you for the honey and wax you have given us, and for being part of our family, as always. We will bring your sisters from the forest here to make a new colony. Rest in peace.”

Each of the children then said a few words and threw in their flower, even John, who told the bees he forgave whichever of them stung him that time and that even so, they made very nice honey.

Nash had no idea what to say. He couldn’t quite believe their feelings for insects—stinging insects at that. He liked honey, but still . . .

He filled in the hole. Solemnly.

As they walked back to the house, he asked Maddy, “Why will you only bring the bees’ sisters from the forest? Why not their brothers?”

Behind him the girls giggled. “Because it’s the girl bees who do all the work,” Jane told him. “The drones—that’s what you call the boys—they don’t work at all.”

“Except for defending the hive,” Nash said.

Jane made a scornful sound. “Drones don’t fight, they can’t even sting! The girls defend the hive, collect the honey, clean the hive, everything. All the drones do is eat.”

Nash and the two boys exchanged glances. “They must be good for something,” he said, feeling the need to find and uphold some masculine virtue in the little creatures.

Maddy waved the children ahead, then turned and gave him a mischievous glance. “Reproduction. It’s their sole purpose in life.”

Nash kept a straight face. “Well, there you are then. Noble chaps, one and all. Doing their duty for king and country.”

She shook her head. “For the queen,” she said. “There’s no king, it’s all for the queen.”

At lunch, which was the inevitable soup and cheese on toast, she said to Nash, “You think it’s peculiar that we had a ceremony for the bees, don’t you?”

“No, not at all,” he lied.

“It’s because of Grand-mère, you see. The bees saved her life.”

His brows rose. “How so?”

Maddy’s mood lifted. “By a very clever trick.” The children exchanged knowing glances and settled down to listen to what was obviously a well-loved tale.

Nash knew his duty. “Tell me.”

“You know how I told you that Papa had helped Mama escape from the Terror, while Grand-mère remained behind? Well, some days later Grand-mère heard people coming for her, just a handful, but nasty. They knew she’d been a beloved servant of the queen. So—”

“She hid herself among—” Lucy began.

“Hush, Lucy, let Maddy tell it,” Jane said.

Maddy smiled and continued. “Grand-mère was at the queen’s little farm, le Hameau de la Reine, at Versailles. The queen and her ladies like to play at being peasants, and they would dress as shepherdesses and milkmaids and milk the cows and so on. And Grand-mère kept the bees that made the queen’s honey.”

She lowered her voice to a thrilling pitch. “They were coming for her, screaming for blood! She had no horse or carriage to escape in, and she knew they would find her if she tried to hide inside. So what did she do?”

The children looked expectantly at Nash, their eyes alight with excitement.

“What?” There was no need to feign his fascination.

“She pulled all the beehives into a circle and sat in the middle of them, wearing her veil and gloves.”

“Did they fin

d her?”

Maddy nodded. “A few did but they were city people and they were afraid of the bees. When anyone came close, Grand-mère hit the hives with a stick and all the bees came boiling out, enraged, and buzzed furiously around, stinging whoever they came across.”

She gave a short laugh. “If they’d known anything about bees they would have waited until dark when the bees retire for the night, but Grand-mère was lucky. The people went looking for easier prey and she managed to escape and make her way to a place she knew in the country.”

The children chorused, “And there she lived happily for the rest of her days.”

“And that, Mr. Rider, is why we in this family love and honor bees,” Maddy finished.

“And we like the honey, too,” Henry added.

They spent the rest of the day working in the garden. Nash was feeling weary, but when Maddy glanced at his face and suggested he stay inside and rest after the midday meal, he refused.

“Helping you with this is the least I can do,” he told her.

“But it’s your first day out of bed. You need to rest. You haven’t finished healing yet.”

But Nash worked doggedly on.

Around four o’clock Maddy called a halt. They’d done about as much as they could for the day, she said. Nash was secretly glad of it. He was exhausted.

“Scrambled eggs on toast for tea, and pancakes for supper,” she declared. “And then we’ll have a story.”

They’d just finished their tea when Maddy, who was facing the window, said, “Mr. Harris! Quick, children, out the back way, please.”

Their faces were alive with curiosity. “Oh, but Maddy . . .” John began.

Maddy held up a hand. “I don’t want you in the cottage while he’s here. Girls, lock up the hens for the night, then take half a dozen eggs to Lizzie’s aunt and ask her for some cottage cheese. Wait there with Lizzie. John, Henry, have you checked Mr. Rider’s horse this evening? No? Then off you go. And call past Lizzie’s and collect the girls on the way home. Now go.” The children ran off.