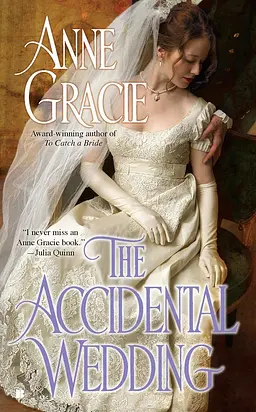

by Anne Gracie

He could still hear the sound of water splashing.

“Are you there, Miss Woodford?” he called out.

“I’m in the scullery.” She sounded startled, a little flustered. She might, he supposed, be bathing in the scullery, though it would be cold there.

“Are you all right?” she said after a moment. “Do you want something?”

He did. He wanted her. “What are you doing?” he asked.

She hesitated. “Just a bit of washing.”

But which bits was she washing? “Can you come here a moment?”

“Is it urgent?”

“Yes.” His voice croaked as he said it. He was rock hard and aching for her.

“Oh, very well.” He heard the sound of dripping water, quite a lot of dripping water. He braced himself.

Would she come to him naked and wet? Or wrapped modestly in a large cloth that would cover her from top to toe, clinging most delightfully to where she was damp.

“What is it?” She came, wiping her hands on a cloth, dressed exactly as she had all day. Covered from top to toe in layers of clothing. Thick layers, dammit, all fastened and buttoned up.

She gave him an expectant, quizzical look. He’d told her it was urgent. He couldn’t think of a thing to say. “Water,” he said finally, like a great stupid. Luckily his voice still croaked.

She brought him a cup of water and he drank it as if thirsty. He was, but not for water. She smelt like beeswax and flowers, but then she usually did.

“Another?” she asked and he nodded.

She fetched another cup and waited, her head bent in thought as he drank it down. And that’s when he noticed her hair. She usually wore it twisted into a knot on the top of her head, but at night she took it down, shook it out into a glorious mass, brushed it, then braided it into a loose, silky plait. Tonight the tips of the braid were unmistakably damp. His fingers itched to unbraid it, spread it across a pillow, and bury his face in it.

“Did you just take a bath?” he asked.

“I was washing the children’s smalls,” she said crisply, but her cheeks flushed rosily, and it wasn’t the light of the fire or the glow of the candles. She took the cup and retreated without saying a word.

He lay back, quietly exultant. He hadn’t been mistaken. She’d bathed. For him. Soon she’d come to bed, fresh and fragrant.

He couldn’t wait.

Seven

She put the cup on the table and disappeared, returning in a matter of moments with a small bundle of twisted cloths. She shook each one out with a snap and hung them on a line strung above the hearth with a rather pointed air, silently emphasizing that she had indeed washed children’s smalls.

His lips twitched. Didn’t mean she hadn’t bathed.

She dumped a pile of lace and feathers and ribbons onto the table. Then she took a hat and proceeded to destroy it.

“What are you doing?”

“Refurbishing a hat. Ladies in the village pay me to make over their old hats: it’s a lot cheaper than a new hat, and I have a talent for it.” Her nimble fingers worked quickly, ripping faded ribbons and squashed flowers from the dowdy headpiece.

“Wouldn’t it be easier to do that in the daylight?”

“Yes, but I’ve been busy.” She bent over the hat.

Firelight danced through her hair and candlelight gilded her skin as she bent over her task with a small frown of concentration. She never stopped working. He’d never seen her just sit and be. It was his fault she was behind with her work, and the thought made him angry.

She removed the last of the old trimmings from the hat then brushed it vigorously all over with a small wire brush.

“How did you come to be living like this?” he asked abruptly.

Her flying fingers stopped for a moment, then resumed their busy work. “Like what?”

“Living in a small laborer’s cottage, apparently the sole support of five young children. From your accent, you weren’t born to this.”

“No.” She took the sad-looking, denuded hat over to the kettle and held it over the steaming spout.

“So how did you come to be here?”

“My father died in debt.” She pressed the hat onto an inverted bowl and smoothed it with her hands.

“Were there no relatives you could turn to?”

“None who wanted all the children. One distant, very rich cousin would have taken Susan. Just Susan by herself. No nasty, noisy boys or inconvenient toddlers, and certainly not Jane. She had the cheek to say to me, ‘Just the pretty one.’ ”

She threaded a needle and began to stitch a ribbon to the hat, her stitches stabbing angrily through the fabric. “Pretty one indeed! Jane is a dear, loving child and just because she isn’t as pretty as Susan . . .” Her needle stabbed into the hat with precise, angry movements. “She said she would consider Lucy when she was older, that she promised fair to be pretty, too.”

“You would have given Lucy away?” he said, surprised.

She turned and gave him a long, considering look. “You think Lucy is my daughter, not my sister.”

“No, not at all—” he began, though indeed he had wondered.

“She’s not,” she said in a matter-of-fact voice. “Yes, she’s a lot younger than the others, and we’re both redheads, but Lucy’s eyes are blue, like her brothers and sisters, and mine are brown.” She smoothed out several strips of colored net ribbon, selected a bronze one, and threaded her needle.

Her eyes weren’t brown, they were the color of brandy or sherry, a luminous dark gold. Intoxicating.

“I apologize, it’s no business of mine.”

She shook her head. “I’m used to people saying it behind my back, so I rarely get the chance to explain. The truth is, Lucy’s mother died not long after giving birth to her. Lucy is the reason Papa sent for me.”

“Sent for you? Why, where were you?” He did the sums. She would have been about eighteen or nineteen when Lucy was born. “In London, making your come-out?”

“No.” She gathered the net onto her needle, forming a ruffle. “That’s why I thought Papa had sent for me, to make my come-out at last. But his plans were . . . otherwise.”

She held up the hat, turning it and examining it from all angles. “What do you think? Will the ruffle suit?”

He gave it a cursory glance. “Yes, very elegant. But you were telling me about your father’s plans. Instead of you making your come-out, he wanted—what?”

She bit off the thread with her teeth. “He wanted me to take charge of the nursery.”

“Where were you?”

“Living in . . . the country with my grandmother. My mother’s mother.” Her mouth twisted ironically. “Living much as I am now—growing vegetables and keeping bees. It’s where I learned to refurbish hats. My grandmother had a flair for such things.”

He glanced again at the hat. It looked surprisingly stylish. Had her grandmother been a milliner? If so, she was a good one. That hat looked almost French. No wonder the ladies of the village used her services.

It was apparent also that her father had married beneath him and wanted to disown the offspring. “Your father couldn’t help?” Surely he could have afforded to support one young girl.

She shrugged. “Papa never did acknowledge anything that wasn’t right in front of him. He was very good at avoiding uncomfortable realities. Besides, Papa never liked my grandmother. And she didn’t like him.”

She worked in silence for a while, the only sound the crackling of the fire in the grate.

He imagined her as a young girl, toiling away in the country, caring for her elderly grandmother, growing vegetables and learning the millinery trade. Then the excitement of being sent for, anticipating her come-out, only to serve as a nursery maid instead. She must have been crushed with disappointment.

She examined the hat with a critical air. “It needs something else. Perhaps some flowers. The fashion this year is for more ornate hats and Mrs. Richards does like to be à la mode.”

/> Women were amazing. How could she know the latest modes, buried here? And that French accent was good. Someone had taught her well. “Did you ever make your come-out?”

She picked over the pile of bits and pieces, putting together a small posy of ribbons and fabric blooms. “No, never. Papa said there was no need. It was too expensive, he said, and he’d already made . . . an arrangement.”

“An arrangement?”

“It did not please me.” He could tell by the set of her firm little chin she wasn’t going to explain any further. She stitched flowers onto the hat band.

“Could your grandmother not help with the children?”

She shook her head. “She died six months before Papa sent for me. I’d written to him of her death, of course, but he didn’t send for me until after his second wife died and he had four young children and a newborn baby on his hand.”

She sewed on the last flower, and added, quite as if it didn’t matter, “Until then, I didn’t even know I had any brothers or sisters. I knew, of course, he’d married again, but in the ten years he left me with my grandmother, he’d never once mentioned children.”

Ten years! And then to find he had a whole other family, and herself the eldest of six.

The hurt, not to have been told . . .

Abruptly, a shard of memory pierced him. He had a brother he’d never been told about. Or was it two brothers? He wasn’t sure. There were remembered sensations of anger. And . . . jealousy? Or hatred of the interlopers. But the details eluded him.

“When did your father die?”

“Two years ago. And all he left were debts and children, so . . .” She shrugged.

“Is there nobody else to help you?”

She held up the hat, turning it and examining it from all angles. “What do you think?” She put it on and turned toward him. He was astounded. How had that stylish-looking hat emerged from those odd bits and pieces. But he wasn’t going to be distracted.

“Very pretty.” So, she was left wholly responsible for children she barely knew, without support from anyone. Working every hour God sent. He watched her packing up her materials.

“You must resent it,” he said quietly.

“Resent what?”

“Having the children foisted on you without—”

“Foisted?” she said in an astonished voice. “I don’t resent the children in the least. I love them. They’re my family, the most precious thing I have. That’s why I refused to let that cousin take in Susan. As long as I can take care of the children, I won’t let anyone split us apart.”

“But—”

“If I do harbor any resentment—and I admit I do—it’s toward Papa for his foolish, selfish, spendthrift ways that left us with nothing—less than nothing—with a pile of debts! But one thing I’ve learned in life is not to waste time in fruitless recrimination—it helps nobody and only embitters you. Now, I think it’s time for bed.” She smiled brightly and disappeared into the other room.

Her words and the dazzling smile that accompanied them caused a shudder of delicious arousal to pass through him.

He lay back and waited, his body thrumming pleasantly, already partially aroused.

She returned a few minutes later, clad in a thick flannel nightgown and a woolen shawl knotted in front, concealing the shape of her breasts. It was cold, he conceded, and flannel was a reasonable choice. But she didn’t need it. He’d keep her warm.

She placed a screen in front of the fire, then hurried away, returning with a roll of bedding.

“What the devil is that?” He sat up abruptly, setting his head spinning. He could see perfectly well what it was.

She arched an eyebrow. “I beg your pardon?”

Damn his language, he thought. “What are you doing?”

She bent to pull the bedding straight and the nightgown drew tight over her hips. His body responded instantly. “I’m making my bed. And then, as the saying goes, I’m going to lie in it.”

“You’ll do no such thing!”

“This is my home, Mr. Rider, and I’ll sleep where I please.”

“You’ll freeze on that stone floor.”

She flipped back a quilt. “It’s not nearly as cold as it’s been the last two nights. I’ll be all right.”

“I won’t allow it.”

“Allow?” She gave him a cool look. “You forget yourself, sir.”

“I forget many things, but I do not forget my obligations as a gentleman,” he said grimly. He flipped back his bedclothes, all thought of seduction gone, and swung his legs over the side.

“What are you doing?”

“If you think I’m going to let a woman sleep on the cold, hard floor while I sleep in her bed, you’ve got another think coming.” He touched his injured ankle to the floor and winced.

“Stop! The doctor said if you tried to use that ankle, you might cripple yourself!”

“It’s entirely up to you,” he told her. “If you persist in this nonsense about sleeping on the floor, then I have no choice but to sleep there instead.” He made a move as if to stand.

“Stop!” She stared at him, frustrated.

He stared right back.

“You’re so stubborn!” she said at last.

He could smell capitulation. “Pot calling the kettle black.”

She clenched her hands. “I will be perfectly all right on the floor.”

“Then so will I. In the meantime, that stone floor is freezing your toes.”

The toes in question curled under his gaze and she stepped onto the rag rug nearby. “If they’re cold, it’s your fault for keeping me from my bed.”

“I’m not keeping you from your bed,” he said. He waved his hand. “Here it is, all toasty and warm, waiting for you.”

“You must know I can’t share a bed with you.”

“Why not? You have the last couple of nights, and emerged quite unharmed. In fact, I’d suggest that you slept the better for having me in the bed. You were certainly warmer.”

“How could you know that?”

He nodded toward her feet. “Your feet were half frozen that first night when you came to bed. You thawed them on my calves.”

She flushed. “I did not.”

He grinned. “That part of the past I do remember, very clearly. Like little blocks of ice, they were. Woke me up.”

There was a long silence. She hovered, undecided.

He tried to sound as disinterested as possible. “You know it’s the most sensible solution. What good would it do you or the children if you caught a chill?”

She bit her lip.

“Come on,” he said in a coaxing voice. “I promise to be a gentleman. And you can bring Hadrian’s Wall with you.” He added ruefully, “Even if I wanted to seduce you, in the state I’m in you could easily fend me off. One biff on the head and I’ll be out like a snuffed candle.” And that, unfortunately, was true.

“Very well,” she said, and he moved back to make room for her. “But nobody must ever find out. If they did . . .”

“How would anyone find out? I won’t tell anyone, and if the vicar asks you, you will continue to lie to him, just as you did today.”

“I did not lie to him,” she said indignantly. “I told him I’d made up a bed on the floor, and I had.”

“Yes, you merely left out the part about not sleeping in it. Perfectly unexceptional. And you’ve made up the bed on the floor tonight, as you said you would, so stop hopping about on the cold stone floor and get into bed.”

She grabbed a quilt from the bed on the floor, rolled it into a Hadrian’s Wall, stuffed it against him, and climbed in after it. She pulled the bedclothes over her, shivering.

“See, you’re half frozen,” he said, and put his arms around both her and Hadrian’s Wall.

“Stop that,” she said, but he could tell a halfhearted objection when he heard it.

“You can warm your feet against my legs if you like,” he invited. The fresh, distinctive scent of he

r and her soap teased his nostrils.

She made a small huffing noise and didn’t move. “You’re pleased about this, aren’t you? she said crossly.

“It’s the only logical choice.” He couldn’t keep the satisfaction out of his voice. His gentlemanly promise had definitely slowed his plans for seduction. But so had his aching head, and there was more than one way to seduce a woman . . .

After a while she stopped shivering.

“I told you,” he murmured. “All toasty and warm.”

“Do your ribs hurt you at all?” she asked in a soft voice.

“No, not a bit—oof! What was that for?” She’d edged an arm under Hadrian’s Wall and elbowed him in the ribs, hard.

“For being stubborn, manipulative, and impossible,” she purred. “And for gloating. Good night, Mr. Rider. Sweet dreams.”

Maddy smiled as she closed her eyes. He deserved it, she told herself. He’d blackmailed her into his bed. Her bed. And as she’d climbed into bed she’d caught a gleam, in the firelight, of a white, triumphant smile.

And as for his arms around her, pulling her against his long body, well, Hadrian’s Wall was some protection, but not much. She’d tried to push him away, but she was so cold and he was so warm it was easier not to resist.

It wasn’t just about the cold, she admitted to herself. Having his arms around her, sharing a bed, it felt . . . lovely. She felt warm, protected, and less alone than she’d felt for a very long time.

Her feet were still cold, but she was drifting off when she felt a stealthy movement in the bed. She feigned sleep, curious to see what he was up to, ready to repulse a rakish advance.

A large, warm foot burrowed beneath the rolled-up quilt that separated them. He hooked it around her feet and slowly drew them toward him. Drawn by the warmth generated by his body, she let her feet be taken and warmed between his calves.

She didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. A wicked, rakish devil he was, to be sure, warming her feet in secret.

She fell asleep with a smile on her face.

Thump! Thump!

Maddy’s eyes flew open. A sick feeling curdled in her stomach. Not again.

Thump! Thump! The door rattled on its hinges but the new bolt held fast. A low moaning came from outside. Unearthly. Terrifying.