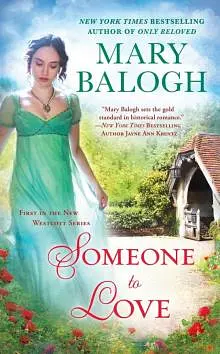

by Mary Balogh

The boy did indeed look dashing in the uniform of the 95th Rifles. And Avery did not doubt his enthusiasm, though there was definitely a slight edge of hysteria to it. Harry would do well—if he remained alive. And perhaps indeed what had happened would be the making of him. He was speaking with a forced bravado now, but he would make it reality. There was something admirable about Harry, after all.

“I do believe you will always turn female heads,” Avery said, looking his ward over without the aid of his quizzing glass, “the color of your coat notwithstanding. You are ready?”

Harry was leaving today to join his regiment, or the small part of it that was in England, replenishing its numbers after losses in battle. Within a day or two they would be embarking for the Peninsula and the war against Napoleon Bonaparte. There would be no time for the boy to ease his way gently into his new role. He might find himself in a pitched battle within days of his arrival.

“Aunt Louise will not shed buckets of tears over me, will she?” Harry asked uneasily. “Leaving my mother and the girls a week ago was one of the hardest things I have had to do in my entire life. Worse than watching my father die.”

“Her Grace will keep a stiff upper lip,” Avery assured him. “Jessica will be another matter.”

Harry winced.

“Her mother has allowed her out of the schoolroom,” Avery told him. “If she were not allowed to say farewell to you, she would probably run away to sea as a deckhand or some such thing and I would have to exert myself to go and fetch her home.”

“As you did with me when I enlisted with that sergeant,” Harry said. “Did I tell you how much you made me think of David confronting Goliath, but with a quizzing glass rather than a slingshot? Devil take it, Avery, but I wish I could simply click my fingers and find myself with my regiment. Not that I do not love my relatives. Just the opposite, in fact. Love is the damnedest thing.”

Was it? But it was indeed hard to be sending Harry off, possibly to his death. “I shall try my utmost to contain my own tears,” he said.

Harry gave a bark of laughter.

The duchess and Jessica were awaiting them in the drawing room. So was Anna.

Avery eyed her with displeasure. She had actually quarreled with him two evenings ago. She had found his company tedious and had stalked away from him, regardless of the curiosity she was stirring among those gathered in their vicinity. He would wager half his fortune that fashionable drawing rooms had been buzzing with the story yesterday and probably would again today unless someone had been obliging enough to wear a yellow waistcoat with a purple coat or elope with a handsome, brawny footman or otherwise arouse some new scandal. And now here she was to sob all over Harry when he least needed it.

“You look very smart, Harry,” the duchess said with hearty good cheer, getting to her feet as she looked him over. “Goodbye, my boy. I will not ask you to make us all proud of you. I know you will.”

“Thank you, Aunt Louise,” he said, shaking hands with her. “I will. I promise.”

Predictably, Jessica dashed into his arms, wailing horribly.

“You will be ruining Harry’s new uniform, Jessica,” her mother said after a few moments, and Jess hopped back and rubbed her hand over the slightly damp patch below one of his shoulders.

“I will n-never accept that you are no longer the Earl of Riverdale,” she told him, “and I will n-never forgive Uncle Humphrey, though one is not s-supposed to speak ill of the d-dead. Nor will I forgive the f-family he hid away while he was alive. They were n-never his real family. You were and A-Abby and Camille and Aunt Viola. But I promised Mama that I would not m-make a scene, and I will not even though she is here and Mama would not send her away. Harry, it hurts my heart to see you g-go and to know you are g-going into such d-danger.”

“I’ll come through safely,” he said, grinning at her. “I am not easily got rid of, Jess. And you will be all grown-up when I return. You almost are now. You will have so many beaux I won’t be able to forge a way through them, and you will have lost interest in a mere cousin anyway.”

“I will never lose interest in you, Harry,” she declared passionately. “I only wish we were not related. But then I suppose I would not even know you, would I? How perplexing a thing life is. Oh, I w-wish you were not g-going. I wish—”

She shook her head and spread her hands over her face, and Harry turned his attention toward Anna, who was standing quietly some distance away.

“Anastasia,” he said.

“Harry.” She smiled at him. “I had to come. You are my brother. But I did not come to burden you with more emotion when I am sure you are already oppressed with it. I came merely to say that I honor and admire you and look forward to the day when I can say it again.”

“Thank you,” he said. Nothing more, though he did not look either angry or resentful that she had come—or happy for that matter.

And then he turned to stride out of the room. Avery went with him as far as the outer doors, but Harry had already made it clear that he wished to leave the house alone. They shook hands, and he was gone. Avery raised his eyebrows when he realized that he felt something suspiciously like a lump in his throat.

He would have walked past the drawing room on his way back upstairs and gone about his own business if he had not heard raised voices from within—or, rather, one raised voice. He hesitated, sighed, and opened the door.

“. . . will always hate you,” Jessica was yelling. “And I don’t care that I am being unfair. I don’t care—do you hear me? I care about Abby and Camille. I care about Harry. I want everything to be back—”

“Jessica.” The duchess, who almost never raised her voice, raised it slightly now. “You will return to the schoolroom immediately. I will deal with you there later. When we have a guest in the house, we always exercise good manners.”

“I don’t care—”

“I shall take my leave, Aunt,” Anna said in that soft voice of hers that was nevertheless clearly audible. “Please do not be angry with Jessica. The fault is mine for coming here this morning.”

“And you will not take the blame for me,” Jessica cried, wheeling on her, fury in her eyes.

“Jess.” Avery spoke even more quietly than Anna, but his sister turned toward him and fell silent. “To the schoolroom. I daresay you are missing a lesson in geography or mathematics or something equally fascinating.”

She left without a word.

“I do apologize, Anastasia,” the duchess said.

“Please do not.” Anna held up one hand. “And please do not scold Jessica too harshly. All of . . . this has been a terrible shock to her. I understand that her cousins are very dear to her.”

“She adores them,” the duchess admitted. “Are you missing a dancing lesson or an etiquette lesson or a fitting?”

“Merely my weekly meeting with the housekeeper,” Anna said. “It can wait. But I will not take any more of your time, Aunt Louise. I will collect Bertha from the kitchen and be on my way.”

“Elizabeth—?” the duchess asked.

“She went to the lending library with her mother,” Anna explained. “They wanted me to go too, but I chose to come here instead to see Harry one last time—at least I hope, oh, I do hope it was not really the last time. But it was a self-indulgence I ought to have resisted, I fear. Good day to you, Aunt, and to you, Avery.”

She moved purposefully toward the door and looked ready to mow him down, Avery thought, if he did not step out of her way.

“Anastasia!” His stepmother’s voice sounded pained. “You are not by chance intending to descend to the kitchens in person to retrieve your maid, are you?”

“I daresay the girl is awash in tea and bread and butter and gossip,” Avery said. “Allow her to finish and find her own way home when she learns that she has been abandoned. I will escort you, Anna.”

She w

as still finding him tedious, it seemed. She raised her eyebrows. “Was that a question?” she asked.

He thought over exactly what he had said. “No,” he said. “If memory serves me correctly, it was a statement.”

“I thought so,” she said. But she did not argue further, and a couple of minutes later they were outside the house and she was taking his offered arm, also without argument.

“Are you still . . . bored with me?” he asked after they had walked in silence out of Hanover Square.

She evaded the question. “Did you really save that man’s life?” she asked him.

Ah, she was referring to Uxbury.

“It is really quite extraordinary that he remembers the incident that way,” he said. “As I recall it, I almost took his life.”

Her head whipped about so that she could gaze into his face. She was wearing a pale green walking dress that was totally unadorned, though it had clearly been made by an expert hand. It emphasized her slender curves, and it struck him in surprise that she was just as sexually appealing as any of the more bountifully endowed females he had always favored. Her straw bonnet, tied beneath her chin with a ribbon of the same color, was surely the plainest hat he had ever seen, but there was something about the shape of it that made it unexpectedly alluring. The curls and wispy ringlets that had adorned her head at the theater two evenings ago had disappeared today, and every last strand of hair had been ruthlessly confined within the knot at her neck. He had not been quite serious when he had suggested that half the ladies of the ton would soon be imitating the simplicity of her style, but really he would not be at all surprised if it happened. Of course, they would need her figure and beauty of face to carry it off.

“I suppose you will not explain,” she said, “unless I ask.”

“Are you sure,” he asked her, “that you wish to hear about the violence I visited upon the person of another gentleman?”

She tutted. “Yes,” she said. “I have the feeling, however, that you are about to say something absurd.”

“I clipped him behind the knees with one foot and set three fingertips against a spot just below his ribs,” he told her, “and down he went, gasping for air. Or not gasping, in fact. There has to be some air moving into the body if one is to gasp, does there not? He turned quite purple in the face, as well he might when he had shattered a costly crystal decanter and probably a table too on his way down. But he had plenty of help surrounding him before I took my leave.”

“Oh,” she said, exasperated, “you have outdone yourself in absurdity. Three fingertips, indeed. He is twice your size.”

“Ah,” he said after nodding to a couple who passed them on the street, “but everyone is twice my size, Anna. Though my fingers are probably as long as most men’s.”

“Three fingertips,” she said again with the utmost scorn. She frowned at him, clearly not sure if he was teasing her or telling the truth.

“One’s fingertips can be powerful weapons, Anna,” he said, “if one knows just how and where to use them.”

“Oh, goodness,” she said. “I do believe you are serious. But why did you do it—if indeed you did? Why did you almost kill him?”

“I was tired of his conversation,” he said, and smiled at her.

She stiffened and moved a few inches farther from him, then turned her head to face forward again. “It was tedious?”

“Excruciatingly.”

He became aware then of footsteps pitter-pattering up behind them at great speed and stopped and turned to see a young girl approaching. She was wearing a stiff new dress, which she was holding above her ankles, and a new bonnet and new shoes, and it took no genius to guess who she was.

“Bertha, I assume?” he asked as she came to an abrupt and breathless halt in the middle of the pavement a short distance behind them.

“Yes, sir, my lordship, your worship,” she said. “Oh, which is it, Miss Snow? I have forgotten if I ever knew.”

“Your Grace,” Anna said. “There was no need to hasten out after me, Bertha. You ought to have stayed a little longer to enjoy yourself.”

“I had already eaten two scones and didn’t need the third,” the girl said. “I’ll be getting fat. You ought to have come and got me, Miss Snow. I am not supposed to let you out without me, am I? Not when you are alone, anyway.”

“But I am not alone,” Anna pointed out. “The Duke of Netherby is escorting me home, and he is a cousin by marriage.”

“However,” Avery said with a sigh, “dukes have been known to devour ladies on the streets of London when they do not have their maids with them to defend them. You did well to follow, Bertha.”

She astonished him by laughing with abandoned glee. “Oh, you!” she exclaimed. “He’s a funny one, Miss Snow.”

“You may follow from that distance,” Avery told her. “Close enough to attack me should I take it into my head to pounce upon your mistress, but far enough not to overhear or—heaven forbid!—participate in our conversation.”

“Yes, Your Grace.” She grinned cheerfully at him as though they were involved in some mutual conspiracy.

“Thank you, Bertha,” Anna said.

“I suppose,” he said as they resumed walking, “you walked arm in arm together on your way to Archer House, talking incessantly and laughing a good deal.”

“Not arm in arm,” she said. “The first time I did that was with you on the way to Hyde Park. There is not much physical touching at the orphanage. Perhaps because we are all crowded together there, we respect what space there is to set us apart.”

But she had not denied chatting and laughing with her maid. What a strange creature she was. And he had to admit he was altogether too fascinated by her.

“My sisters are in Bath,” she said, “living in a house on the Crescent with their grandmother, Mrs. Kingsley. She must be wealthy—the Crescent is the most prestigious address in Bath. Do you know anything about her?”

“Her husband was born into money and did not squander any as far as I know,” he said. “I believe she too is of a moneyed background. Hence the marriage between your father and their daughter. Their son chose the church as a career and has remained with his flock, though I very much doubt he has needed to since the death of his father. Camille and Abigail will be well looked after, Anna. They will not starve. Neither will their mother.”

“If only it were a matter of just money, I would be reassured,” she said. “Abigail has been to the Pump Room with her grandmother for the morning promenade, but Camille has not been seen.”

“And who, pray,” he asked, “is your spy?”

“That is a horrid word,” she said. “I begged my friend Joel to keep an eye upon them if at all possible, to find out if they have been able to make a new life for themselves. I suppose I pictured them in near destitution. He discovered who their grandmother is and where she lives, and he saw Abigail entering the Pump Room one morning, though he did not go in himself. He found out it was she.”

“An admirable friend,” he said.

“He called upon Mr. Beresford for me too,” she said, “though I then had to write for myself. He would not reveal anything to Joel.”

“Beresford?” He raised his eyebrows.

“The solicitor through whom my father supported me at the orphanage,” she reminded him. “I have not had a reply yet. I hope he can tell me who my mother’s parents are or were, and where they live or lived—the Reverend and Mrs. Snow, that is.”

“Anna,” he said, “did they not turn you out after your mother’s death and abandon you to your father’s dubious care?”

“That is what Mr. Brumford was told,” she said. “But I need to discover for myself. “

They were on South Audley Street, moving in the direction of Westcott House.

“You enjoy causing yourself pain?” he asked her. “Is it not to be avoide

d at all costs?”

She turned her head to look into his face, and their steps slowed. “But life and pain go hand in hand,” she said. “One cannot live fully unless one faces pain at least occasionally. You must surely agree.”

He raised his eyebrows. “No pain, no joy?” he said. And actually he did agree. Life, he had learned, was a constant pull of opposites, which one needed to bring into balance if one was to live a sane and meaningful life. He knew it with his head, his heart, and his soul. Was there a part of him that did not know it, though, or that at least resisted putting it into practice? Had he erected a barricade against pain and thus denied himself joy? But did not everyone avoid pain at all costs?

What had his master meant by love? He had been unwilling to explain, and Avery had been teased by the question for more than a decade.

“Oh,” she said, “I am not sure life can be defined with such simplistic phrases.”

He knew a moment of hilarity as he imagined having such a conversation with any other lady of his acquaintance—or with one of his mistresses. Or with any of his male acquaintances, for that matter. He took his leave of her after seeing her inside the house, having refused her invitation to go up to the drawing room for refreshments. He found himself taking his leave of her maid too.

“Goodbye, Your Grace,” she said, grinning cheekily at him. “You did not pounce on Miss Snow and devour her after all, did you? But was it because I was there to rush to her rescue, or would you not have done it anyway? I will never know, will I?” And she laughed merrily at her own joke.

So did the very young footman, who was clearly new. Another orphan from Bath?

Avery was too astonished even to use his quizzing glass. But he did shake his head when he was outside the house again and startled two ladies on the other side of the street by chuckling aloud.

Thirteen