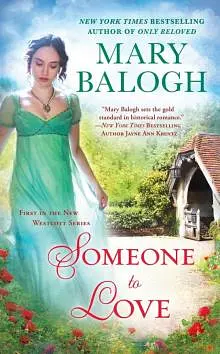

by Mary Balogh

I still wish I could come home. I believe I would too if I had not put temptation out of the question when I brought Bertha here. She is exuberantly happy. She asked me yesterday if she could possibly have her half day off on Saturday instead of Tuesday as assigned by the housekeeper, because Oliver’s half day is on Saturday. I said yes, of course, and she is in transports of delight at being able to report that they are officially walking out together.

And there—I changed the subject and never did get around to saying exactly what I am asking of you. I do not know! But oh dear, Joel, can you possibly, possibly keep an eye upon my sisters? I do not know them and I probably never will, but I love them. How ridiculous is that? At least keep me informed if you possibly can. Are they social outcasts, or are they making some sort of new life for themselves? The end of another page is coming up fast, and I must not start another. Know yourself

the dearest friend in the whole world of

Anna Snow

P.S. Forgot to thank you for your lovely news-filled letter. Consider yourself profusely thanked. Out of space. A.S.

* * *

It had indeed been decided among the powers that be, namely Anna’s aunts and grandmother, that her first official appearance in society would be at the theater, in the duke’s private box, where she would be seen by a large number of the people who were now avidly eager to meet her but would not be called upon to mingle with them to any great degree. She still had much to learn, apparently, about polite behavior and who was who among the ton.

Anna had never watched a live dramatic performance, though there were theaters in Bath. She looked forward to doing so now, especially as she had read and enjoyed the play in question, Sheridan’s The School for Scandal. It would not have occurred to her to be nervous if everyone else had not told her that she must be—even Elizabeth.

“You will probably find it a bit of an ordeal, Anna,” she said during an early dinner on the evening of the performance. “Watching the play onstage is the least important reason for attending the theater, you know.”

Anna looked at her and laughed. “No, I do not know,” she said. “What else is there?”

“There are tiers of boxes,” Elizabeth explained, her eyes bright with merriment, “filled with the crème de la crème of society, and the floor or pit, which is occupied mostly by gentlemen. And everyone is out to ogle everyone else, to observe and comment upon gowns and cravats and jewels and hairstyles and the newest pairings and flirtations and courtships. The gentlemen in the pit gaze up upon the ladies, and the ladies, highly offended, gaze down upon the gentlemen from behind their fluttering fans. Half of society marriages are probably conceived at the theater.”

“Oh dear,” Anna said. “And the other half?”

“In the ballroom, of course,” her cousin said. “London during the Season is known as the great marriage mart.”

“Oh dear,” Anna said again.

Bertha had helped Anna into her turquoise evening dress, which seemed very grand to both of them as it shimmered in the light and flattered Anna’s figure with its expertly fitted bodice and softly flowing skirt, despite the modest simplicity of its design and lack of ornament. Bertha had set to work on her hair, brushing it until it shone and then twisting it into a knot high on the back of her head before curling the long tendrils she had left free to trail along her neck and over her ears and temples. She had been learning diligently from Elizabeth’s maid.

“Ooh, it looks ever so nice, Miss Snow,” she had said immodestly as she stood back to assess her handiwork. “All you need now is a prince.”

She giggled and Anna laughed.

“But I really would not know what to do with one, Bertha,” she said. “I would be quite tongue-tied.”

Though a duke was not of much lesser rank than a prince, was he? She had not seen the Duke of Netherby since that afternoon when he had taught her to waltz—though it was her dancing master who took the credit. She had still not decided whether he attracted or repelled her, and that was strange. Surely the two were polar opposites. But she did know that the waltz was the most divine dance ever created.

“You must be ever so frightened, Miss Snow,” Bertha had told her as she gathered up the brush and comb and curling iron. “You are going to be seen by all the nobs. But you are one of them now, aren’t you? Well, hold your head up high and remember what you used to tell us in school—that you are as good as anyone.”

“It is gratifying,” Anna had said, “to know that at least one of my pupils was listening.”

Cousin Alexander arrived with his mother soon after dinner to convey them to the theater in his carriage. He could very well be the prince of any fairy tale, Anna thought, especially in his black-and-white evening finery. And he was the perfect gentleman. He complimented both her and his sister upon their appearance and handed them all into his carriage with solicitous care before taking his place beside Elizabeth with their backs to the horses.

“You must be nervous,” he told Anna, smiling kindly at her. “But you have no need to be. You look elegant, and you will be surrounded by family.”

“Of course you are nervous, Anastasia,” Cousin Althea said, patting her hand. “It would be strange if you were not. I daresay some people will be at the theater tonight specifically because they have got wind of the fact that you will be there. Your story has caused a great sensation.”

“And if she was not nervous before climbing into the carriage, Mama,” Elizabeth said, “she is doubtless shaking in her slippers by now. Ignore us, Anna. I am very glad the play is to be a comedy. There is enough tragedy and turbulence in real life.”

Was she nervous? Anna asked herself. It was all very well to tell herself that she was as good as anyone. It was another to step into a theater filled with people who were apparently anticipating a sight of her as much as they were looking forward to watching the play. How silly, really.

There was a huge throng of people and carriages about the theater, but precedence was important in London, Anna remembered as a lane opened to allow the carriage of the Earl of Riverdale through, and miraculously a space cleared for it before the doors. The Duke of Netherby was waiting there with Aunt Louise, but it was Cousin Alexander who handed his mother and Anna down onto the pavement before taking Anna’s hand firmly through his arm and patting it reassuringly. He offered his other arm to his mother. The duke helped Elizabeth alight and escorted her and Aunt Louise inside to the crowded foyer and upstairs to his box.

He was dressed in a dark green tailed evening coat with gray knee breeches and embroidered silver waistcoat with very white linen and stockings and an elaborately tied neckcloth. His jewelry was all silver and diamonds, and his hair waved golden about his head. He was all grace and elegance and hauteur, and a path opened before him just as one had outside before the earl’s carriage.

He had once kissed her. No, he had not. He had comforted her. And he had once waltzed with her, and she had felt as though they were dancing upon the floor of heaven.

Stepping into his private box was breathtaking, to say the least. It was like an intimately enclosed space that was missing one wall. Or perhaps it was like walking onstage, for it was close to the stage and almost on a level with it, as Anna was almost instantly aware, and visible from every part of the theater, from the boxes arranged in a horseshoe on their own level to the tiers above it to the floor below.

There were crowds of people already in attendance. The noise of conversation was almost deafening, but surely she did not imagine the extra buzz followed by a marked decrease in sound and then a renewed surge of conversation. And all heads appeared to be turned their way. Anna knew because she was looking. She might have looked down and pretended there was nothing beyond the safety of the box, but if she did not look out from the start, she might never find the courage to do so, and that would be mildly absurd when she had come to watch a play. But of

course there were a duke and duchess in this box too, as well as an earl and a baron and baroness—Lord and Lady Molenor, Uncle Thomas and Aunt Mildred, were awaiting them there. All these people were not necessarily looking at her.

There were two other gentlemen in the box. Aunt Louise introduced them to Anna as Colonel Morgan, a particular friend of her late husband, and Mr. Abelard, a neighbor and friend of Cousin Alexander. They both bowed to Anna while she inclined her head and told them she was pleased to make their acquaintance.

“Everyone, it would appear, is looking at you, Lady Anastasia,” the colonel told her, his eyes twinkling from beneath bushy gray eyebrows. “And may I be permitted to tell you how elegant you look?”

“Thank you,” she said.

Cousin Alexander seated her close to the outer edge of the box next to the velvet balcony rail and took the chair beside hers. He engaged her in conversation while everyone else took their places. He was obviously doing his best to set her at her ease. And what about him? This must be an ordeal for him too since he had just been elevated to the ranks of the aristocracy and did not spend much time in London. Anna smiled back at him and returned his conversational overtures.

The duke was amusing Elizabeth. She was laughing at something he had said. Mr. Abelard, seated beside Cousin Althea, had his head bent toward hers as she talked.

And then, finally, the play began and the noise of conversation and laughter died to near silence. Anna gave her whole attention to the stage and within minutes was both engrossed and enchanted. She laughed and clapped her hands and lost all awareness of her surroundings. She was with the characters upon the stage, living the comedy with them.

“Oh,” she said when the intermission brought her back to herself with a jolt, “how absolutely wonderful it all is. Have you ever seen anything so exciting in all your life?” She turned to smile at Cousin Alexander, who was smiling back at her.

“Probably not,” he said. “It is particularly well-done. We may wait here for the second half to begin. There is no need to leave the box.”

All about the theater, Anna could see, people were getting to their feet and disappearing into the corridor behind their boxes. The noise level had become almost deafening again. Elizabeth was leaving with her mother and Mr. Abelard.

“We will remain here, Anastasia,” Aunt Louise said, raising her voice. “Your appearance here tonight is sufficient exposure for a start. If anyone should call here to pay his respects, all you need do is murmur the barest of civilities.”

“You really need not feel intimidated, Anastasia,” Uncle Thomas added. “Only the very highest sticklers will venture to knock upon the door of Avery’s box, and we will engage them in conversation. All you need do is smile.”

The duke himself was on his feet, though he had not followed Elizabeth into the corridor. He was taking snuff from a diamond-encrusted silver case and gazing about at the other boxes, a look of boredom on his face. The snuff dispensed with, he returned the case to a pocket and strolled closer to Anna.

“Anna,” he said, “after sitting for so long I feel the urge to stretch my legs. Accompany me, if you will.”

“Avery,” the duchess said reproachfully, “we decided in advance that it would be altogether wiser on this first occasion—”

“Anna?” He raised his eyebrows.

“Oh, thank you,” she said, realizing suddenly how long she had been sitting. She got to her feet and he escorted her out into the corridor, where crowds milled about, hailing one another, conversing with one another, sipping drinks, and—turning to look at Anna and the Duke of Netherby. He nodded languidly at a few people, raised his jeweled quizzing glass almost but not quite to his eye, and that magic path opened again so that they could stroll unimpeded.

“It must have taken you a lifetime to perfect the art of being a duke,” she said.

“Anna.” He sounded almost pained. “If there is an art I have perfected, it is the art of being me.”

She laughed, and he turned his head to look at her.

“You do realize, I suppose,” he said, “that you are learning a similar art? By tomorrow half the female portion of the ton will be expressing shock at the simplicity of your appearance, and the other half will be suddenly dissatisfied with the fussiness of their own appearance and begin shedding frills and flounces and ribbons and bows and ringlets until London is wading knee-deep in them.”

“How—”

“—absurd, yes, indeed,” he said. “And your behavior, Anna. Laughter and applause in the middle of a scene? And no private conversation with those sharing your box when the action onstage grew tedious? Laughing again now, out here?”

“The play did not grow tedious,” she protested. “Besides, it would be impolite to the actors and to one’s fellow audience members to talk aloud during the performance.”

“You have much to learn,” he said with a sigh.

But she knew he did not mean what he said. He had not talked during the performance. She would have noticed.

“I daresay,” she said, “I am a hopeless case.”

“Ah,” he said, raising one finger to bring a waiter hurrying toward them with a tray of glasses. “I would rather say the opposite.”

“I am a hopeful case?” She laughed.

He took two glasses of wine and handed her one as a tall, handsome gentleman with shirt points of such a stiffness and height that he could barely turn his head stepped up to them.

“Ah, Netherby,” he said. “Well met, old chap. I have not set eyes upon you since that evening at White’s when I had some sort of seizure. I must thank you for summoning help so promptly. My physician informed me that you probably saved my life. I was confined to my bed for a week as a precaution, but I have made a full recovery, you will be pleased to know.”

The duke’s quizzing glass was in his free hand, and he was holding it to his eye.

“Ecstatic,” he said, his voice so cold that it almost dripped ice.

Anna looked at him in surprise.

“Perhaps,” the gentleman said, turning his attention to Anna, “you would do me the honor of presenting me to your companion, Netherby?”

“And perhaps,” the Duke of Netherby replied, “I would not.”

The gentleman looked as astonished as Anna felt. He quickly recovered himself, however.

“Ah, I understand, old chap,” he said. “The lady is not quite ready for a full public unveiling, is she? Perhaps another time.” He swept Anna a deep bow and moved away.

“But how very . . . rude,” Anna said.

“Yes,” the duke agreed. “He was.”

“You,” she cried. Sometimes his affectations were too much to be borne. “You were very rude.”

He thought about it as he sipped from his glass. “But the thing is, Anna,” he said, “that he did say perhaps. That implies a choice, does it not? I chose not to present him to you.”

“Why?” She frowned at him.

“Because,” he said, “I would have found it tedious.”

“And I find your company tedious,” she retorted, handing him her glass—he dropped his quizzing glass on its ribbon in order to take it—and turning back toward the box.

Too late she realized that she had attracted attention. A lane opened in front of her but for different reasons, she suspected, than when it had opened for the duke. She entered the box alone, but the duke was close enough behind her that no one remarked upon the fact. Cousin Alexander was standing talking with the colonel and Uncle Thomas while Aunt Louise and Aunt Mildred were conversing with each other, their heads almost touching.

“You are looking flushed, Anastasia,” Aunt Mildred remarked. “I daresay it was hotter out in the corridor than it is in here.”

“I am flushed with enjoyment, Aunt,” Anna said as she took her seat again. Her eyes met the duke’s, and she would not l

ook away because he did not. He raised his eyebrows and had the gall to look almost amused.

He would have found it tedious to present that gentleman to her, indeed. How humiliating to the man himself, and how . . . rude to her, giving the impression as he had that she was not yet ready to be presented to polite society. What did he expect? That her mouth would pour forth obscenities and blasphemies, all learned at the orphanage?

And then, before looking away and resuming his own seat, he smiled at her. A full-on, dazzling smile that made him look like a golden angel and made her feel several degrees warmer than just flushed.

She disliked him, she decided. She despised him. And it was definitely repulsion she felt for him rather than attraction.

She smiled as Cousin Alexander seated himself beside her again and engaged her in intelligent conversation about the play.

Twelve

“You know, Avery,” Harry said cheerfully as he surveyed himself in the long pier glass in his dressing room. “I think maybe this was the best thing that could have happened to me. While I was my father’s only son and heir, I could not even think of joining the military. I certainly could not do so after his death. But I have always envied those fellows who could, and now I can be one of them with a clear conscience. It is all going to be a great lark. And I am going to like wearing a green rather than a scarlet coat. Every officer and his dog wear scarlet. This will turn heads. Female heads, that is. Do you not think?” He turned to grin at his guardian.