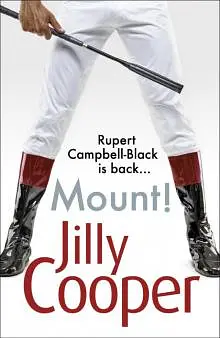

by Jilly Cooper

Multi-married Old Eddie had always been a groper. The reason he’d had to give up his very successful television programme, Buffers, was because he wouldn’t stop lunging at the female researchers and presenters. Unfortunately, on a golden autumn day towards the end of October, his daughter-in-law Taggie returned from shopping to find, to her horror, that Forester her greyhound, who suffered from separation anxiety, had shredded Old Eddie’s rubber sheep Mildred all over the drawing-room carpet.

Knowing how upset Eddie would be, Taggie was frantically gathering up Mildred’s remains when, wandering into the room, confronted by Taggie’s long, still-coltish legs and delectable bottom, Eddie shoved his hand up her crimson skirt, pulling down her tights, as his fingers crept underneath her knickers.

Taggie’s shriek of surprised horror, when she realized it wasn’t Rupert, coincided with her husband coming in through the front door and catching his father crimson-handed. His bellow of rage had all the dogs, including Forester with his mouth full of shredded Mildred, rushing in from the kitchen, and Old Eddie scuttling upstairs.

‘That is the final straw, the filthy letch,’ roared Rupert.

‘No, no,’ pleaded Taggie, crimson as her skirt. ‘It’s OK, he’s sweet and always a bit odd when the moon’s full.’

‘He’s out of control. He’s going into a home tomorrow.’

‘He’d never get in – they’ve got a five-year waiting list.’

‘I took the precaution of booking him a place at Ashbourne House a year ago,’ said Rupert triumphantly.

‘We can’t, he’d hate it.’

Next moment there was another squawk, as Marjorie, Eddie’s whiskery carer, bustled in.

‘We’re busy,’ snapped Rupert.

‘Ay’m sorry, Taggie, Eddie has just put one hand up my skirt and fondled my breast with the other.’

‘Extraordinary how my father always goes for the same type,’ drawled Rupert. For a second his eyes met those of Taggie, who was trying not to laugh.

‘Ay’m afraid ay can’t tolerate that kaind of behaviour.’

‘You won’t have to any more,’ said Rupert. ‘My father’s going into a home.’

Marjorie’s face fell. No more Taggie’s cooking and a very pretty room, with Sky and her own microwave.

No more carers, thought Rupert ecstatically, and there was now no reason why Taggie, who had been looking desperately tired, couldn’t abandon Penscombe for a month and join him on a round trip to Singapore, Japan, Hong Kong and China.

Taggie, to his fury, refused. There was far too much to do at home, she said, particularly in the run up to Christmas; filling up the deep freeze for the office party, finding turkeys for the tenants and presents for staff and family.

She and Rupert parted, not friends.

The moment Rupert, Cathal, his Irish travelling Head Lad, who was in charge of the horses once they left the yard, his stable jockey Lion O’Connor, and two stable girls – sweet, smiling Lark who loved Young Eddie and horses, and ‘woluptuous, wolatile’ Marketa from the Czech Republic who loved the opposite sex and Safety Car – flew off to the Far East with six horses, the family, as if by telepathy, knowing the coast was clear, moved in.

Tabitha Rannaldini, Rupert’s daughter, and Caitlin, Taggie’s sister, claiming the need for more quality time with their husbands, dumped their children, dogs and nannies on Taggie. Janey Lloyd-Foxe immediately invited herself for Christmas because she was so sad, exhausted and missing Billy.

Taggie was further demoralized, being dyslexic, by her step-grandchild, Timon Rannaldini, calling her ‘a crap granny’ because she couldn’t read him a bedtime story. Even worse was Timon’s sister Sapphire announcing: ‘I think Daddy and Mummy are getting a devalse and Mummy says she, me and Timon will be coming back to live with you.’

Oh God, thought Taggie in terror, we’ve already got Young Eddie as a permanent fixture. At least with Marjorie gone, the chocolate biscuit consumption had plummeted.

Taggie’s withers had also been wrung by putting Old Eddie in the care home. Sewing nametapes on all his clothes was like sending a little boy off to prep school, particularly when he sobbed and sobbed, clung on to the banisters, wept all the way on the journey and even louder when she left him. Taggie felt so dreadful that she insisted on visiting him every day, which took up even more of her time.

On her tenth visit on a dank, grey November afternoon, she was passed going the other way down the drive by Brute Barraclough. Brute, the foul trainer who was so unkind to his darling wife Rosaria, but had no intention of leaving her because she did all the work and kept owners and horses sweet. Brute, the on-off lover of both Gav’s ex Bethany and Janey Lloyd-Foxe.

On arrival, Taggie was immediately summoned into the office of Mrs Ramsey, the head of the home, who grumbled that she had just had to deal with Brute Barraclough who, discovering that someone’s rich old mother, Mrs Ford-Winters, was a resident, had dropped in and managed to sell her a horse called Geoffrey.

‘I’m not sure if she can afford it and our fees. You racing folk, Mrs Campbell-Black! And I’m afraid your father-in-law has been rather wayward.’

Old Eddie, it seemed, had been sliding his hand under too many tartan rugs.

‘And I don’t quite know how to say this, Mrs Campbell-Black, but in the afternoon your father-in-law’s been wandering round, slipping his penis into our lady residents’ mouths when they’re asleep in front of the television. There have been complaints.’

Taggie fought hysterical laughter and was tempted to suggest the lady residents took their teeth out.

‘I’m terribly sorry, Mrs Campbell-Black,’ Mrs Ramsey concluded, ‘but I’m afraid you’ll have to take your father-in-law back home.’

‘Oh please, can you keep him a day or two,’ begged Taggie, ‘while I sort something out?’ Oh God! Rupert would go berserk to have the house full of Treasures again. Nor had she told him that Helen, his ex-wife, as well as Janey, were angling to stay for Christmas. She couldn’t bother him when he was abroad concentrating on the horses and networking with rich Chinese.

For a second she thought how heavenly it would be if she could have gone with him or if their own children Bianca and Xav had been able to return from abroad for Christmas.

Quailing, she rang up Mrs Simmons at the carers’ agency, who asked if Taggie wanted Marjorie back. ‘She was very happy with you.’

‘Not really, so embarrassing when my father-in-law made a pass at her. Might be better to have someone a little younger.’

By luck, said Mrs Simmons, they had a white Zimbabwean called Gala Milburn.

‘She’s a widow of thirty-four, had rather a rough time, not been long in this country but she’s a good cook and an excellent worker. We’ve had very good reports. She could be free in the run up to Christmas.’

13

In the year 2000, a land invasion had started in Zimbabwe when gangs of armed blacks, claiming to be veterans of Mugabe’s Liberation Army, began seizing white-owned land, shooting farmers in the face, battering them to death, assaulting and torturing to death any black workers who remained loyal, ransacking houses, burning tobacco barns, butchering pets and livestock, and riding Land Rovers for fun into herds of giraffe. Everywhere, mud huts sprang up on raped and ruined land.

Gala and Ben Milburn had had a beautiful farm, but as their land was near a mine containing precious minerals, including emeralds worth £300,000 each, they were not likely to be left alone. During a prolonged court case to keep the farm, Ben and Gala were endlessly harassed by veterans.

The day after they won their case, their farm was burnt to the ground. Ben, who was a passionate conservationist and who doubled up as a game warden, was away from home. He had been trying to curb the excesses of a Chinese mafia warlord, a Zixin Wang who, not content with stripping mines of their emeralds and diamonds, was also targeting rhino horn and elephant tusk worth £60,000 each.

In SAS-style operations, Mr Wang’s poacher gangs would load heli

copters on to trucks so they needn’t log a flight-path. Armed with machine guns, they would then mow down rhinos and elephants, hack off their horns and tusks, load these into the helicopters and fly them away.

Attempting to save a baby rhino whose mother had been gunned down, Ben was gunned down himself with fifty bullets in his body.

Gala, who’d been shopping, returned to discover at the smouldering farm that limbs had been hacked off their cows and horses, so they staggered around moaning on three legs, until she put them out of their misery by shooting them. Even more horrible, her adored Staffordshire Bull Terriers and Ben’s black Labrador, Wilson, had had their throats cut and been hung up on posts. Only then did Gala learn that Ben had been murdered – but she had no means of fighting back. If you take on the Chinese mafia in Zimbabwe, you’re dead in the (lack of) water.

All these horrors were so undeserved because Gala was a darling: big, brave, optimistic, intelligent with thick blonde curly hair, sleepy, kind dark eyes, a tawny complexion and an embracing smile. She also had a voluptuous body with big breasts, a big, uppity bottom and powerful thighs tapering down to slim ankles. Added to this was a frequent laugh and a lovely soft voice, like a warm breeze in the acacia trees.

Her once-happy life had now become unimaginably dreadful. She had lost all her money and, like many Zimbabwean women, found the only solution was to come to England and work as a carer, a job often satisfying but in Gala’s case so demanding and even harrowing, it almost blotted out some of the previous horrors.

In the five months she had been in England, Gala had looked after a retired Colonel with dementia, who one moment would be ordering her to get out because he was going to call the police, the next moment asking her when they were going to bed.

The next client was in a wheelchair, but trapped Gala in her bedroom, leering and masturbating in the doorway. He also steered her hand towards his penis every time she washed him.

She then moved on to a husband and wife, who never stopped complaining about her excellent cooking and were terrible snobs. The husband, who had multiple sclerosis, was also a multiple groper. But when they had people to lunch, Gala was mortified to hear the wife saying, ‘Do you think she knows how to lay the table?’ And when once Gala had remarked that Princess Diana had been very beautiful, had snapped: ‘What do you know about our Royal Family?’

In fact, in Zimbabwe, Gala had had many of her own servants, and had taught African maids to cook, even delivering one of their babies single-handed.

In each new place, as a carer, it was a panic to locate the potato peeler, the tin opener, where to put everything as you unloaded the dishwasher and not to drive people crackers asking questions all the time.

One crotchety old lady kept looking for things for her to do, dispatching her to clean the car or weed the garden when she should have been taking a two-hour break, expecting her to make a pint of milk last a week and complaining that she was using too much lavatory paper – ‘you only need two squares at a time.’

Unlike other carers, Gala couldn’t storm out as she had nowhere to stay in England except where she was employed. Gala’s parents were both dead, but she had an older sister Nicola, who was married with three children, lived in Cape Town and was often tapping Gala and Ben when he was alive for money. It was Nicola with whom Gala stayed when she was doing her week-long training to become a carer. This included how to use hoists to lift disabled clients, how to make them comfortable, give them their pills on time, and to ignore frequent abuse, because the old and, particularly those losing their minds, tend to lie or to forget, or say the first thing that comes into their heads.

The other problem was although the hours were punishing with only a two-hour break in the middle of the day, Gala had to spend long periods watching, with these clients, television programmes in which she had no interest. This left her too much time to mourn the devastating loss of her handsome, noble Ben, her beautiful farm, her lovely animals and Pinstripe her zebra, who had pulled a cart. Why, this is hell, nor am I out of it.

Somehow, she managed to hide her panic attacks, and smiled and smiled, repeating that she was ‘fine, fine, fine’. Zimbabweans are a naturally kind and happy people, and if you were called out so often in the night, at least it cut short the terrible nightmares.

Gala was currently working for a mad old woman in the depths of Gloucestershire, filling in while their permanent carer was on holiday. By day, the old woman stood by the window, saying: ‘When is Mummy coming to take me home?’ By night, the big house creaked and groaned in the wind and the old woman laughed madly like the first Mrs Rochester.

Gala was therefore passionately relieved when the agency rang her about a possible next post.

‘Could you pop in on your break?’

Gala borrowed the family car, then, after Zimbabwe’s wide straight roads, terrified herself driving along narrow, winding, high-banked lanes and negotiating roundabouts and one-way streets through towns.

Mrs Summers at the agency, however, cheered her up with strong black coffee, chocolate biscuits and the words: ‘You’ve been doing really well in some challenging jobs, so here’s something more exciting. The job is at Penscombe, home of Rupert Campbell-Black and his wife Taggie. She’s an angel, the sweetest woman you could ever meet. Rupert’s tricky, likes to call the shots, but he’s pretty attractive.’

‘Pretty?’ Gala couldn’t believe her ears.

‘They’ve got masses of horses and dogs. You OK with animals?’

For a moment Gala couldn’t speak, overwhelmed by visions of Dobson and Gregory, her Staffies, and Wilson, Ben’s black Labrador, hanging from those poles gushing with blood. Could she bear animals again?

‘No, I’ll be fine.’

‘There are cleaners, a PA and masses of staff in the yard and the stud, so you may end up cooking breakfast for the stable lads, but your main job will be caring for Rupert’s father, whose dementia is advancing. He was quite a celebrity himself in a television programme called Buffers.’

‘Buggers?’

‘No, Buffers. Old generals and admirals arguing about military campaigns, so if you chat to him about the war, you’ll be well away. Don’t think you’ll be called out much in the night. Frankly, Taggie needs a carer more than Eddie.’

When Taggie met Gala at Cotchester station, both were impressed by how attractive the other was.

Here’s surely one Rupert won’t object to, thought Taggie, praying on the other hand that Old Eddie wouldn’t get carried away too soon. Taggie, in fact, looked shattered, her big silver-grey eyes reddened from seeing so many of her beloved foals setting out, all glossy, plump and unaware of their futures, to the sales. But she was still as beautiful and slim as the brindle greyhound, who rattled his tail and laid a comforting chin on Gala’s shoulder as they drove back to Penscombe.

‘Forester’s rescued so he hates being left behind,’ explained Taggie. ‘I’m sure you’ll like Eddie, he’s very affectionate but a bit wayward, unless you grab each of his hands with one of yours. Nearly there,’ she added, swinging into Rupert’s chestnut avenue, passing a sign saying Visiting Mares, which to Gala sounded rather like Jane Austen.

She had Googled the house beforehand but never expected it to be quite so large or impressive. Her room looked south over a wooded valley, but with the leaves off the trees there seemed an almost African amount of cloudy sky reflected in Rupert’s blue and white lake.

Braving the cold, leaning out of her window, she gasped at the extent of the operation. To the right was a huge yard for the horses in training and half a dozen distinctive royal-blue lorries, entitled Rupert Campbell-Black Racing and decorated with galloping emerald-green horses. Beyond, carved out of the wood, was the stud, where his stallions strutted their stuff. There were barns for the visiting mares and cottages for the staff, a tangle of flat and downhill gallops for every trip and surface imaginable, salt- and fresh-water swimming pools, and everywhere else lush fields full of glorious horses in

royal-blue rugs.

‘Oh wow, treble wow!’ sighed Gala, shutting the window.

Her room enchanted her almost more with its palest pink walls, rose-red curtains, violet and pink checked counterpane, and paintings of flowers in different seasons. There was a dull red desk with Chinese carvings on the lid for her to write letters on, and to add to her comfort, a television, a little radio, and an electric blanket which she hoped she wouldn’t fuse with her tears. On the bedside table were a tin of shortbread, a vase of pink geraniums and copies of Tatler, Country Life, Dogs Today and The Lady for her to read.

‘Oh, quadruple wow!’ Taking a piece of shortbread, Gala found it still warm from the oven.

The only downside was that the room was at the top of the house, which meant lots more steps for aching legs accustomed to Zimbabwean one-storey houses. Old Eddie’s room was just below on the next floor. Taggie introduced him to Gala downstairs. He was wearing a tweed jacket with a badge on the lapel saying Old Men make better lovers, and acorn-brown cords with three fly-buttons undone. He was also sporting a green woolly hat, and carrying a brick on a plate, from which he attempted to cut her a slice.

‘I’m fine, thank you,’ said Gala. ‘I’ve just had a delicious piece of Mrs Campbell-Black’s shortbread.’

‘This is Gala,’ said Taggie. ‘She’s going to look after you from now on, instead of Marjorie.’

‘Marjorie’s gorn orf,’ said Eddie, ‘but we’re not divorced. ’Spect she’ll want half the house.’ Then, seeing how young and luscious Gala was, his eyes gleamed. ‘You can stay in my half if you like.’

But apart from the odd lunge and having to watch lots of military and sporting programmes, and locate occasional porn channels and then scarper, Eddie and Gala got on famously. Every day he liked her to read him The Times’ Death Column, to see ‘who’s pushed orf and check I’m still alive’.