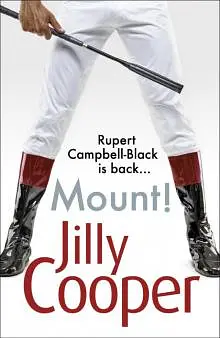

by Jilly Cooper

He then insisted she took him down to the stud to see Love Rat, who always trotted over and laid his great white face against Eddie’s before accepting several Polos. She was soon taking Eddie on jaunts, including a first visit to Tesco’s where, seeing a small boy and his sister riding in their mother’s trolley, he exclaimed: ‘Good God, do they sell children as well?’

That was one of the tragedies of being a widow, not being able to tell Ben things that had made her laugh. But at least James Benson, the Campbell-Blacks’ smooth, still-handsome doctor, supplied Eddie with sleeping pills, which ensured that Gala’s nights were usually uninterrupted, except by her own nightmares.

14

For Gala, the best part of the job was getting to know Taggie. Over a wonderful dinner of moussaka on her first night, Taggie confessed how she loathed the foals going off to the sales, and how, because she couldn’t read or write very well, she dreaded coping with Christmas cards. She and Rupert got thousands and had had one printed this year with Love Rat, rearing up noble and unusually virile on the front.

The house seemed to swarm with impossibly spoilt children. Gala, used to Zimbabwean children, who didn’t answer back and stood up when grown-ups came into the room, was shocked. Dogs were also everywhere: Rupert’s black Labrador Banquo, two Jack Russells, Cuthbert and Gilchrist, nicknamed the Brothers Grin, and the ex-racing brindle greyhound Forester, who chased anything that moved and kept taking single shoes into the garden. One morning was spent searching for Eddie’s teeth, until Banquo wandered downstairs clacking them. On another occasion, Forester dropped them in the drive and a horsebox ran over them.

Desperately missing her Staffies, and Wilson, also a black Labrador, Gala palled up with Banquo, who was missing Rupert and barked every time a door banged or a car drew up on the gravel.

‘Your master’s coming home soon,’ she kept reassuring him.

Meanwhile Taggie had so much to do and Gala didn’t think Rupert’s PA, Geraldine, who’d clearly like to be the next Mrs Campbell-Black, protected Taggie enough. Gala therefore took over the job, seeing off the vicar, for example, when he tried to persuade Taggie to read one of the Nine Lessons for a carol service. She was also soon helping Taggie out with Christmas cards – ‘if only people would put in their surnames’ – feeding and getting the children to bed, feeding and walking the dogs.

But reciprocally it was Gala’s special kindness that touched Taggie. She would find her bed made, or wander wearily upstairs at night to find it turned down and a light on. Gala always left the kettle full up, and put back plugs if she’d pulled them out.

When Taggie staggered home from a punishing afternoon Christmas shopping in Cheltenham, during which she had bought Gala four thermal vests, several pairs of thick socks and some dark-brown Uggs, she found Gala had cooked her a wonderful Zimbabwean dinner.

‘This is so gorgeous,’ enthused Taggie, embarking on a second helping of chicken breasts cooked with mustard and honey. ‘Did Eddie have some?’

‘He did, he seemed to like it.’

‘Must be in heaven. Marjorie never flavoured anything. To wind her up, Rupert once put a salt lick in Eddie’s bedroom. I had to pretend it was for Mildred – that was Eddie’s pet rubber sheep, which naughty Forester shredded. You must keep those Uggs away from him.’

‘They’re bliss,’ Gala stretched a foot out, ‘but I’ll never take them off, so Forester won’t get them. In Zimbabwe we lived on the edge of a conservation area where animals wandered in and out. You’d find elephants in the swimming pool, and monkeys were always pinching eggs. One day Ben came home and found a baboon sitting on a chair in the kitchen eating a banana.’

Rupert was always so busy, particularly since he’d become obsessed with nailing Leading Sire. Even when he was at home, he’d spend the evenings planning who would ride what horse and which races they’d run in, and watching re-runs of races at home or abroad so he could blast the jockeys next day. Taggie found it lovely to have another person to talk to, not a demoralizer like Janey, Helen or Geraldine or even her own mother, Maud.

Gala revealed very little about her terrible past, but showed Taggie a photograph on her mobile of the handsome, rugged Ben, displaying marvellous legs in khaki shorts and hugging a baby rhino.

‘He was a Rhodi,’ said Gala, ‘which means very straight, macho, chauvinistic and conservative, but he was a total softie around animals.’

‘He’s absolutely gorgeous. Does it get any easier?’

‘Not really, but it’s not unrelenting, you do have sudden moments of happiness,’ Gala smiled at Taggie, ‘like now. I love being here.’

The cold, however, got colder and Gala put on even more jerseys, an overcoat with a hood, three pairs of socks tucked into her Uggs, and was passionately grateful for the electric blanket and assorted dogs who, with Rupert away, took every opportunity to get into bed with her.

One December afternoon, when Old Eddie was sleeping, Gala strayed out in her break to look at the horses. Chatting to her favourite, the little chestnut, New Year’s Dave, who was certainly not going to any sales, she met up with Michael Meagan, known as Roving Mike – the foxy, lazy, engaging Irish work rider, who for a consideration sometimes helped out in the stud. He was now walking out Dardanius, the newest stallion, who would start covering for the first time on 15 February.

‘He’s beautiful too,’ sighed Gala.

‘Dardanius,’ announced Mike, ‘will be one of tree tings: he’ll be popular and successful, or in Japan or in a can.’

‘That’s awful,’ gasped Gala. ‘They don’t go for meat here, Taggie wouldn’t allow it.’

‘A stallion’s useless if he isn’t popular,’ Mike told her.

Love Rat, recognizing Gala from her visits with Old Eddie, was whickering for Polos as they passed his box.

‘He’s fifteen tree, Love Rat, the perfect size,’ volunteered Michael. ‘Wonderful legs, always pricks his ears for photographers – the perfect specimen, but he’s lazy. Peppy Koala, on the other hand,’ he pointed to a handsome chestnut, ‘is our busiest stallion. He’s covered 400 mares in three seasons.’

‘Almost as many as you,’ quipped Pat Inglis, the stud manager coming out of Love Rat’s box. Then, as Gala moved down the row to stroke Titus Andronicus, who was gnawing away at his half door: ‘Don’t touch him, for God’s sake. He’ll have your hand off.’

‘Who was Titus Andronicus?’ asked Gala.

‘Some general who killed an enemy Queen’s sons, then served them up for her to eat in a pie. Hardly Nigella,’ grinned Pat.

‘Like to come out for a drink tonight?’ asked Mike.

‘I’d love to, but I’ve got to look after Eddie. Taggie’s going over to her parents’.’

Taggie had her work cut out, but Gala found it hard sometimes not to be jealous of the beautiful house, the glorious pictures everywhere, the lovely mural of the hunt in the long gallery, all those fantastic horses and dogs; even the badly brought up children had their moments. If only she and Ben hadn’t waited, she would have his child now – but how could she possibly have supported it?

And then there was Rupert, who was still away, now in Hong Kong. The place was evidently very relaxed without him. Impossibly handsome and arrogant, he seemed to challenge and mock her from every photograph.

On her break on a later afternoon, Gala had dropped in on another new friend, Louise Malone, a very pretty stable lass nicknamed Lou-easy because she was so free with her favours, particularly when vets and farriers treated her own horse Bennet for nothing. Louise was cleaning tack and reading Hello!. On the tack-room wall amidst a faded rainbow of rosettes from Rupert’s showjumping past was a photograph of him hugging his favourite mare, Cordelia, after she’d won the Oaks.

‘Lush, isn’t he?’ commented Louise.

‘He’s old, fifty-seven,’ protested Gala.

‘I dunno,’ Louise put her head on one side, ‘he has to fight off women breeders – and gay ones too for that matter. And as

a boss he’s the real deal. The lads grumble but they call him “Guv” and tip their hats to him. He wants everything done perfectly – and by yesterday. Luckily one’s usually got a horse to sit on or cling on to when he’s around, because he does make your knees give way. He doesn’t seem old, just well fit, and it’s such heaven when he praises you. And he can be kind. An owner gave me my horse, Bennet, when he retired from racing and Rupert lets me keep him here.’

It was the eve of the mighty Hong Kong Cup, a mile and two furlong, invitation-only race, which meant a horse had to be asked to enter.

‘There’s a two million dollar first prize,’ explained Louise, ‘plus a huge bonus on offer, if you win three races in three continents. Rupert’s entered Love Rat’s latest wonder colt, Libertine, who won the Coolmore stakes at Flemington and the Diamond Jubilee Stakes at Royal Ascot. If he nails this one tomorrow morning, it’ll mean a gigantic dollop of prize money. Having been beaten by Isa Lovell as Leading Trainer this year, Rupert’s hell bent on clinching it. We’ll all have a happier Christmas if he comes home victorious.’

15

‘It’s the Hong Kong Cup tomorrow morning,’ Taggie said to Gala as they loaded the dishwasher. ‘I do hope I wake in time.’

‘Can’t we record it?’

‘We can, but Rupert loves me to watch the big races, and since Billy died,’ Taggie’s voice faltered, ‘he … well, he likes to ring me immediately afterwards. I wish you’d met Billy, he was so lovely.’

Having had a scalding bath to get warm, Gala found Old Eddie fast asleep and sucking his thumb in her bed, and managed to heave him out and back into his own. Once in her bed, she was so wracked by bad dreams, she gave up and finished her latest Ian Rankin.

At four o’clock, curious to see what Rupert looked like, she put on her Uggs and six jerseys over her pyjamas and, taking Eddie’s baby alarm, crept downstairs into Rupert’s office and turned on At the Races, where the team were already revving up for an earlier race, the Hong Kong Vase. Soon a crocodile of yawning dogs filed in and clambered on to the dilapidated sofa, to keep her warm.

Gala’s eyes were soon distracted, noting a big oil painting of a black Labrador and a smaller, very attractive oil of Billy Lloyd-Foxe. Everywhere were framed photographs of Rupert and Taggie’s adopted children Xav and Bianca, of Rupert’s daughters Tabitha and Perdita, triumphing at eventing and polo, and of the pick of his 3,400 winners at the racetrack. There was also a gorgeous photograph of Rupert and Billy laughing together at the Olympics, back in the 1970s. Rupert was certainly breathtaking then.

Suddenly she caught sight of the Stubbs and wriggled out of a duvet of dogs to examine it in more detail. Rupert Black on Third Leopard. She was transfixed by the glossy splendour of the horse and the arrogant beauty of his rider, the white shirt showing off the perfect jawline, the curling-brimmed hat tipped over the long, narrowed blue eyes. How seldom sex appeal travelled down the centuries, Gala thought, although Charles II always looked as though he’d be pretty exciting in bed.

And there in the portrait was Penscombe Court itself, ghostly through the trees, with swans gliding on the lake. ‘Pen’ was the term for a female swan – perhaps that was where the house’s name originated.

Then she heard a thump of tails, followed by a step, crossed herself and nearly fainted as the ghost of Rupert Black sauntered in. Clinging on to Rupert’s desk, breath coming in great gasps, she slowly digested the fact that this identical twin of the man in the painting was wearing a dinner-jacket. He had taken off his black tie, and his blond curls were spilling over his forehead and the collar of his dress shirt. His blue eyes weren’t quite focusing and he was carrying a bottle of champagne.

‘Hell-lo, hell-lo.’ He had a definite American accent. ‘You must be Great-grandpa’s new carer. Lucky Great-grandpa. I’m Young Eddie, and I have been texted by all the guys in the yard and stud about you.’ And getting a glass out of Rupert’s drinks cupboard, he filled it up and handed it to her.

‘It’s a bit early,’ stammered Gala, noticing light sneaking under the curtains.

‘Or a bit late, depending on your viewpoint. Admiring the Stubbs? Lovely, isn’t it? Grandpa’s got another one, of mares, in the living room.’

‘This one’s exactly like you.’ Carers weren’t supposed to drink. Gala took a guilty slug.

‘Exactly,’ said Eddie. ‘A classic case of pre-potency. Happens in horses, so why not in humans? Grandpa’s even more like Rupert Black than I am. The picture was on show in the National Gallery last year, and when Grandpa sauntered into the press preview followed by Banquo, no one complained about dogs not being allowed, he has such force and charisma.’

Eddie then looked at the television. ‘We’d better watch this race.’ Taking her hand, he pulled her down on the sofa beside him, sitting disturbingly close, with only Cuthbert, the Jack Russell, between them.

‘How you getting on with Great-grandpa?’ he asked.

‘Learning a lot about the First and Second World Wars. He’s sweet. Even when he’s in bed, he tries to leap up when I come into the room.’

‘Not the only thing that leaps up.’ Eddie examined her, and took another slug from the bottle. ‘You are well fit, Mrs Milburn. Why were you called Gala?’

‘It means “rejoicing” in Old French.’

‘Nice name. Under all those layers I cannot tell what shape you are, but you are definitely a M.I.L.F.’ As he leaned forward to kiss her, Gala jumped away on to Gilchrist, who squeaked.

‘Sorry, darling,’ she apologized. Then: ‘What’s a M.I.L.F.?’

‘Mother I would like to fuck.’ Eddie’s grin was so unrepentantly engaging, Gala couldn’t be cross.

‘Actually I’m a widow, without any children.’

‘Omigod, so young, what happened to your husband?’

‘He was murdered,’ said Gala tonelessly.

Eddie rolled his eyes. ‘I’d have murdered him to get at you.’

‘It’s true.’ Gala was about to storm out, when he caught her hand and, being very strong, pulled her back on to the sofa.

‘What happened?’

‘He was trying to protect a baby rhino from a gang of poachers who’d hacked off its mother’s horn, so they gunned him down.’

‘Omigod.’ Eddie put an arm round her shoulders and buried his lips in her rigid cheek, his light blond curls mingling with her dark blonde ones. ‘You poor, poor babe. How awful. God, I’m tactless.’ There was a pause. ‘But I’d still like to fuck you.’

Gala was ashamed how his words cheered her.

‘Where have you been?’ she asked.

‘To the States to see my parents and tonight to a birthday party.’ He took another slug and when he tried to fill up Gala’s glass and she put her fingers over it, he lingeringly licked off the spilled champagne.

‘I need a carer,’ he told her. ‘You could bath me all day, and keep me on the straight and narrow. I’ve got to ride two races at Plumpton tomorrow.’

‘You’d better stop drinking then, or your grandfather won’t be very pleased.’

‘He won’t know.’ Eddie glanced at the television. ‘Talk of the devil.’

In a stall off the pre-parade ring, Rupert, with his back to camera, could be seen calming down the young, dapple-grey Libertine, recently off the plane and about to face the biggest, loudest crowd of his life. Then he moved on to Safety Car, rubbing him down with a damp cloth, then drying him off with a dark-blue towel, soothing him as might a boxer’s second. Marketa, the big and busty Czech with huge slanting dark eyes, a red, generous mouth and thick black hair drawn into a pony tail, was brushing Safety’s mane and straggly, much less thick tail and chatting to him, so he was nearly asleep by the time they saddled him up.

Rupert, Gala noticed, had the broad shoulders and long lean body perfect for an off-white suit. Then as he turned round, she gasped, ‘Oh wow!’ He was gorgeous. He had a much harder, stronger, less vain and self-indulgent face than his ancestor Rupert Black, and

it was shown off not by lustrous curls, but slicked-back blond hair to reveal a wonderful forehead and beautifully shaped head, which he now hid with a Panama that had been hanging on a nearby palm tree.

As he, with Lark leading Libertine and Marketa leading Safety Car, set off for the parade ring, a cluster of press in Day-Glo yellow waistcoats swooped like canaries, then fluttered off without a word as Rupert stalked straight through them.

‘Grandpa loathes the press,’ said Eddie. ‘Look – he’s wearing his lucky blue tie and his lucky blue and green striped shirt. He gets spooked without them. Taggie has to wash the shirt before every race day.’

The cameras were now concentrating on impossibly shiny and beautiful horses being led round the parade ring, and showing glimpses of the lovely racecourse surrounded by sea, emerald-green woods, and buildings soaring to a sky bluer than Rupert’s tie.

‘Who’s riding Libertine?’ asked Gala.

‘Lion O’Connor, Grandpa’s stable jockey. He’s very conscientious, watches a video of every runner in every race, leaves footprints all over the track where he’s walked the course a hundred times to see where the good ground is. Always does his homework, unlike me; lacks the killer instinct, also unlike me. Old Teddy Matthews, a geriatric living in Hong Kong and who used to work for Grandpa, is riding Safety Car, who’s 100–1. It’s probably Safety’s last race. He’s nearly eleven.’

The huge crowds were ever increasing, the women in pretty dresses but hatless, the men wearing baseball caps. Many spectators had bizarrely dressed up as horses, or mice topped with huge nodding heads, big teeth and staring eyes, enough to spook any horse. Gala herself was spooked to see so many affluent Chinese, conjuring up visions of Zixin Wang who would never come to trial for Ben’s death. She began to tremble uncontrollably.

Unaware of the reason, drawing her towards him, Eddie kissed her lips, long and so lovingly that she found herself no longer worrying if she’d cleaned her teeth recently enough, and parting her lips and kissing him back.