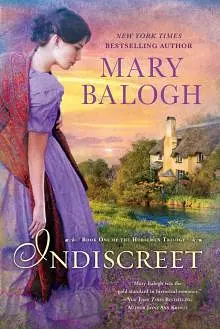

by Mary Balogh

The kiss did not last long, but far longer than it ought to have lasted. He looked back into the water. She presumably did the same thing. He was shaken. He did not know quite where this was headed and he liked to be in control of his affairs. She had refused to be his mistress. And he had been given the firm impression that she had meant it. Kisses for the sake of kisses were pointless especially when they set one on fire. But there was nowhere else for them to lead. He certainly was not interested in any permanent sort of relationship.

“For the sake of my self-esteem,” he said, “you must admit that it was not because you did not want to, was it?”

There was a lengthy silence. He did not think she was going to answer. Perhaps she had not understood his question. But she did answer eventually. “No, it was not because of that,” she said.

It would have been easier if she had not admitted it. Damnation! What did she want out of life? Only contentment and peace? Not pleasure? Though there was another possibility, of course.

“I suppose,” he said, his voice harsher than he had intended it to be, “you want marriage again.”

“No,” she said quickly. “No, never that. Not again. Why would any woman willingly make herself the property of a man and suffer all the humiliation of submerging her character and her very identity in his? No, I am not trying to tease you into making me an honorable offer, my lord. Or any other type of offer either. I meant my refusal the other evening, and if you believe me to be a tease and take that kiss as evidence, then I apologize. It was not meant to tease. It was not meant to happen at all. I am going home now. Alone, please. I will not get lost, I assure you. Toby!” she yelled.

She hurried across the bridge and onward as soon as her terrier made its appearance from among the trees to pant eagerly at her. He did not try to accompany her. He stayed where he was, his elbows on the balustrade, staring down into the water.

He might have stood there for a long time if the crackling of undergrowth had not brought his head up again. He thought she was returning for something. But it was merely one of Claude’s gardeners or gamekeepers, who looked at him a little curiously, pulled on his forelock, and continued on his way.

It was a good thing, Lord Rawleigh thought, that the man had not happened by a few minutes sooner.

7

THE villagers of Bodley-on-the-Water were finding that their lives had brightened considerably. The weather had been unseasonably sunny and warm for a long stretch of days so that the trees were noticeably green and the early-spring flowers were all in bloom with the promise of more to come as green shoots appeared in the gardens even of those not reputed to be blessed with green thumbs. A few fluffy white lambs were frisking on spindly legs in a few fields alongside their shaggier and yellower mothers.

And of course Mr. and Mrs. Adams were back home with their houseguests, and one or more of them appeared in the village or at least passed through it almost every day. A few of the villagers were even blessed with invitations to the house. The rector and his wife were invited several times of course. They were both of the gentry class—Mrs. Lovering was second cousin to a baron. Mrs. Winters was invited once. Miss Downes was invited to tea with the ladies one afternoon at the request of Lady Baird, who remembered her from a long time ago. Unfortunately, Mrs. Downes was too frail to leave her home in order to accompany her daughter. But Miss Downes had reported that Lady Baird was to call one afternoon.

There was to be a dinner and ball at the house one evening. Everyone from miles around with any claim to gentility would be invited to that one, of course. There was to be a proper orchestra instead of just the pianoforte that was played at the occasional village assembly in an upper room at the inn. The greenhouses behind Bodley House were to be ransacked for floral arrangements for the dining room and ballroom.

None of the plans were a secret just as none of the daily activities of the family and guests were. The servants at Bodley were not unusually loose-tongued, but most of them were local people with families either in the village or on the farms about it. And one of the footmen and a few of the gardeners frequented the tavern during their free hours. Mrs. Croft, the housekeeper, was a friend of Mrs. Lovering. News concerning people in whom everyone had an insatiable interest could not be kept entirely under wraps. And nothing was secret, of course.

Unfortunately, the line between news and gossip has ever been a fine one.

Bert Weller, into his fourth mug of ale at the tavern one evening, reported seeing Mrs. Winters walking her dog among the trees inside the walls of Bodley very early that morning. There was nothing so strange about that. Mrs. Winters was ever an early riser. She was often out at the first cockcrow. And she frequently walked in the park, as many of them did. Mr. Adams had informed them they might, though they were not sure that Mrs. Adams approved of their taking such liberties.

The only strange thing—and perhaps it was not strange at all, Bert conceded—was that Viscount Rawleigh had been in the woods too, not very far away, standing on the old bridge, staring down into the water while his horse grazed nearby. Indeed, it had looked for all the world as if Mrs. Winters was coming from the direction of the bridge.

Perhaps they had met and exchanged morning greetings, someone suggested.

Perhaps they had met and exchanged more than morning greetings, Percy Lambton suggested, with a leer and a glance all about him for approval.

But he met none. It was one thing to comment on hard fact and even to speculate a little. It was quite another to instigate malicious rumor. His lordship was their Mr. Adams’s brother—his twin brother—and Mrs. Winters was a respectable citizen of their own village, even if no one knew where she came from or what her life had been like before she came to live at Bodley-on-the-Water.

Perhaps they had met by accident and walked together. They would have been presented to each other at the house when Mrs. Winters was invited there, after all.

They would make rather a handsome couple, someone observed.

Ah, but he was a viscount, others remembered. There was too large a social gap even though she was almost without doubt a lady.

“Or a former lady’s maid who has learned to ape her betters,” Percy Lambton suggested.

The conversation drifted to other matters as Mrs. Hardwick refilled mugs.

But somehow word spread. And it aroused interest in its hearers, though very little malice. It aroused enough interest that they watched with more than usual attention for any sign of an attachment between so great a personage as Viscount Rawleigh and their own Mrs. Winters. There were three incidents before the night of the dinner and ball. Three very minor incidents, it was true, but then, to people who lived in such isolation from centers of activity and gossip, even small incidents could assume a significance beyond the facts.

• • •

EVERYONE from Bodley House attended church on Sunday morning. Catherine watched in some amusement from her pew as Mrs. Adams, at her regal best, led the procession down the aisle to the padded pew at the front, where she always sat, though not all of them could fit on that favored seat, of course. Most of them had to sit on bare polished wood behind her.

The Reverend and Mrs. Lovering had been invited to the house to dinner again last evening. She, Catherine, had not. It had been a significant omission, considering the fact that Mrs. Adams was one lady short in her guests. Clearly she was punishing Catherine for having had the temerity to be in the music room alone with Viscount Rawleigh. Not that it had been particularly improper, but Mrs. Adams wanted him to have eyes only for her sister for the coming weeks. Any other single women between the ages of eighteen and forty must be seen as a threat.

Juliana sidled into the pew beside Catherine, as she sometimes did, and smiled up at her in conspiratorial fashion. Mrs. Adams did not appear to miss her. She probably assumed that her daughter was with one of the guests. Catherine winked back.

She had had an invitation to the dinner and ball to be held next Friday, but that was hardly surprising either. It was not easy in the country to assemble enough guests to enable one to call a gathering a ball. Every last body was important to the success of the occasion.

She was not sorry to be in Mrs. Adams’s bad books. She had been quite happy during the past three days not to set eyes on Viscount Rawleigh. She stole a look at him now seated on the padded pew beside Miss Hudson and two places from his brother. Goodness, but they looked alike. It seemed amazing that such handsome dark looks could be duplicated.

That kiss! It had been a mere meeting of lips. Nothing else. There had been no more to it than that. But it had left her seared, devastated. It had haunted her for three days and woven itself into all her dreams at night.

It was not so much the fact that he had stolen it as the fact that he had not. She had known it was coming. She would have had to be an imbecile not to know. The air had been charged there on the bridge. She could have broken the tension. She could have said something. She could have moved. She could have continued with her walk. She had done nothing.

It was he who had kissed her. It was he who had moved his mouth to hers—and his lips had been parted. Her own role had been quite passive, though she feared that once his mouth was on hers, she had pushed her lips back against his. She had tried to persuade herself that he was entirely to blame, that it really had been a stolen kiss—after he had assured her that he did not seduce women early in the morning.

But it had not been a stolen kiss. It had been something shared. She was at least equally responsible for it. She had not avoided it because—well, because she had wanted it. She had been curious. Oh, no, that was nonsense. She had been hungry. Simply that.

But how could she cling now to the righteous indignation with which she had greeted his visit to her cottage and his conversation in the music room? She was a hypocrite. But she wanted nothing more to do with him. She had thought herself past all possibility of such foolishness.

Oh, the eternal attraction of the rake, she thought with an inward sigh, looking down determinedly at her prayer book and bending an ear to the whispered confidences of Juliana. She had ridden up with her uncle Rex yesterday and he had galloped his horse when she had begged him to and then her mama had scolded him and told him she had been ready to have the vapors and Papa had laughed and told her that Uncle Rex had been the best horseman in the British cavalry and then Mr. Gascoigne . . .

But then the service began and Juliana had to be shushed—with a smile and a wink.

It had been Catherine’s intention to slip out of church just as soon as the service was at an end. She had no wish to come face-to-face with any of the party from Bodley House. But in the event it did not happen that way. Juliana had another story that she was burning to tell. She gave an excited account of the afternoon she had spent at Pinewood Castle, where Lord Pelham had taken her up onto the battlements and she had been frightened and Uncle Rex had taken her down to the dungeon and she had been frightened, though it was not really a dungeon because there was a barred gateway onto the river and Uncle Rex had said that only romantics believed it was a dungeon. In reality it had probably been a storehouse for supplies delivered by water.

By the time the story came to an end everyone was outside and everyone had had a good look at her in passing, since Juliana was seated and prattling beside her. So much for disappearing without being seen, she thought wryly.

Juliana darted out ahead of her and even then Catherine hoped to be able to slip away unnoticed. But it seemed that the whole congregation was gathered on the church path or on the grass at the edges of the churchyard. And the Reverend Lovering, stationed at the top of the steps, kept her hand in his after shaking it and commended her on the arrangements of crocuses and primroses she had set at the altar.

“We must be thankful for the blessing of flowers, even the least splendid blooms of the early spring, with which to adorn our humble church for the eyes of our illustrious guests,” he said. “I take it as a decided mark of respect for the cloth, Mrs. Winters, being too humble to believe that there is anything personal in the matter, that all Mr. Adams’s guests, including Viscount Rawleigh, have seen fit to worship with us this morning.”

“Yes, indeed,” Catherine murmured.

But then Lady Baird came to greet her, bringing her husband and Mrs. Lipton with her. And somehow Lord Rawleigh was there too, bowing slightly to her and fixing his eyes on her. She feared—she very much feared—that she was blushing. She tried desperately not to think about their last meeting.

That kiss!

She talked brightly to Lady Baird, Sir Clayton, and Mrs. Lipton. And took her leave of them as soon as she politely could.

“Mrs. Winters,” a haughty and rather bored voice said as she turned away, “I shall escort you home, ma’am, if I may.”

Almost the full length of the village street. There was the bridge and then Mrs. Downes’s house, then the rectory and the church, and then the whole village before the thatched cottage at the opposite end. And the whole village and half the countryside and all the family and guests from Bodley House were still assembled in the churchyard and on the path.

It was nothing very remarkable, of course. They were going to be in full sight of everyone for every step of the way. She had been escorted home from church before now. If almost any other man had suggested the same thing, she would not have felt the dreadful embarrassment and self-consciousness she felt now. But the one thing she could not do was to follow instinct and assure him that there was no need. That would invite comment.

“Thank you,” she said, walking down the path and out onto the street ahead of him. She willed him at least not to offer his arm. He did not. Why on earth was he doing this? Could he not realize that she wanted nothing further to do with him? But why would he realize any such thing? She had permitted him to kiss her during their last encounter. She felt dreadfully mortified, and she felt that every eye of every member of this morning’s congregation must be on their backs and that everyone must know that they had met alone in the woods three mornings ago and that he had kissed her.

Pray God, she thought for surely the hundredth time, that Bert Weller had not seen Lord Rawleigh in the woods after he had seen her that morning.

“Mrs. Winters,” Lord Rawleigh said now. “I seem to have done you a disservice.”

Only one? To which one was he referring, pray?

“You were not at dinner last evening,” he said, “or at the informal dance in the drawing room afterward, though Clarissa clearly found the uneven numbers provoking. My guess is that you have fallen from grace and that it is my fault. The music room incident, you know.”

“Nothing happened,” she said, “except that I played Mozart rather badly and that you told me you wondered.”

“And you administered a magnificent set-down,” he said, “to which I was given no time to retaliate. Clarissa was, of course, annoyed to find us together. You are altogether too beautiful for her peace of mind, ma’am.”

Foolishly, the compliment pleased her. “She need not fear,” she said. “You are welcome to Miss Hudson or to any other lady of Mrs. Adams’s choosing, as far as I am concerned. It really matters not one iota to me.”

“And I matter not one iota to you,” he said with an audible sigh. “How dreadfully lowering you are to a man’s self-esteem, Mrs. Winters. Why did you allow me to kiss you?”

“I did not—” she began, and bit the words off short.

“You might well halt midsentence,” he said, “when you have just come from church. You were about to utter the most atrocious bouncer. My question stands.”

“If I did,” she said, “I regretted it instantly and have regretted it ever since.”

“Yes,” he said, “one does feel one’s—aloneness at such times, does one not? Have you relived it as often as I

have during the past three days—and nights?”

“Not a single time,” she said, outraged.

“For which I cannot accuse you of lying, can I?” he said, looking at her sidelong. “I have not relived it a single time either, Mrs. Winters. Perhaps a score of times, but that would be a low estimate, I believe. You have not by any chance changed your mind about a certain answer you gave to a certain question?”

They had reached the cottage. She opened the gate, stepped hastily through it, and closed it firmly behind her.

“I most certainly have not, my lord,” she said, turning to glare at him. Why must men believe that one kiss denoted one’s willingness and even eagerness to surrender all?

“A pity,” he said, pursing his lips. “You have whetted my appetite, ma’am, and I hate to have my appetite aroused when there is no feast with which to satisfy it.”

She was outraged. What she would really like to do was reach across the gate and slap him hard across the face, she thought. It would be wonderfully satisfying to see the mark of her fingers redden across his handsome cheek. But the thought that someone farther along the street might have vision perfect enough to see it happen denied her this pleasure. Someone might also notice if she wheeled about and stalked off up the path to her door in high dudgeon.

“I am no feast, my lord,” she said, “and you will never satisfy your appetite on me. Good day to you.” She turned with slow dignity for the benefit of anyone interested in staring down the street at them and made for the door, behind which Toby was having a fit of hysterics.

She made the mistake of glancing back before going inside and thereby marred the effect of her exit line. He was staring after her with pursed lips and what looked suspiciously like amusement in his eyes. He was enjoying this, she thought indignantly. He was entertaining himself at her expense.