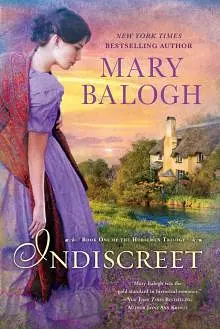

by Mary Balogh

Mr. Gascoigne had to work to control his nervous horse. He grinned while he did so. Lord Pelham swept off his hat and inclined his head to Catherine. Lord Rawleigh stooped down from his saddle and swept up her terrier, who favored him with one more indignant and surprised yip and then settled, panting and cock-eared and floppy-tongued, across the horse in front of the viscount. He had capitulated to the enemy that easily.

“Mrs. Winters,” Lord Pelham said, “you complete the beauty of the morning. I did not know there was a lady alive who rose this early.”

“Good morning, my lord,” she said, half curtsying to him. He had lovely white teeth, she noticed, and very blue eyes. He was quite as handsome as the viscount and certainly more charming. Why was it that she could look at him and speak with him without feeling even one irregular skip of the heartbeat? “This is the very best part of the day.”

“I shall have to trade my horse,” Mr. Gascoigne said, chuckling as he swept off his hat and made his bow to her. “I shall never live down the ignominy of having had him take fright at a mere dog. But then, if I were a dog and you were my owner, ma’am, I would bark as fiercely in your defense too.”

“Good morning, sir,” she said, laughing. “I do assure you his bark is altogether worse than his bite.” Another hand-some gentleman, with laughing eyes and easy charm. No flutters of the heart.

She turned her head before the situation could become awkward—as it had outside her cottage two days ago. “Good morning, my lord,” she said to Lord Rawleigh, who was scratching an ecstatic Toby behind the ears. A third handsome gentleman, really no more so than the other two. Her stomach tied itself in knots.

“Ma’am.” He held her eyes as he inclined his head.

The situation was awkward after all. She should have been able to smile and walk on. But Toby was still up on the viscount’s horse, looking as if he would be happy to stay there for the rest of the morning.

“I suppose,” Mr. Gascoigne said, “we cannot pretend that we are going your way, Mrs. Winters?”

She smiled at him.

“We cannot pretend we are going her way, Nat,” Lord Pelham said. “Alas. She would acquire stiff neck muscles from looking up at three horsemen while we conversed. And her dog might well frighten your horse into spasms.” He chuckled.

Mr. Gascoigne laughed with him. “One of us could offer to let her ride while we walked,” he said. “That would be marvelous gallantry.”

They were teasing her, quite lightly, quite harmlessly. Viscount Rawleigh merely gazed down at her, his hand absently smoothing over Toby.

“I came out for a walk and exercise, gentlemen,” she said. “And so did Toby.” She glanced up pointedly at him and noticed how long-fingered and strong and masculine the viscount’s hand looked against her dog’s back.

He leaned down without a word and set Toby back on the road. Her dog wagged his tail and then trotted on ahead to resume his walk.

“Good day to you, ma’am,” Lord Rawleigh said. “We will not keep you.” He had not smiled or joined in the teasing.

She walked on, listening to the sounds of their horses grow fainter behind her.

Just a few weeks, she thought. That was all. And then life would get back to normal again. Or so she fervently hoped.

But she knew it would not be as easy as that.

• • •

“CHARMING,” Mr. Gascoigne said. “Utterly charming. There is something to be said for unfashionable country garb, is there not? And quiet country surroundings?”

“This is not good,” Lord Pelham said. “Three of us salivating over the same female. Unfashionable country garb looks charming only on someone who would look lovely even without it, Nat. Especially without it, by God. But this place is alarmingly womanless, Rex—no offense to Claude’s sister-in-law.”

“I thought that was the idea,” the viscount said. “We are all to a certain extent escaping from entanglements with females, are we not? Eden from his married lady, Nat from his unmarried one, me from—well, from a former fiancée. Perhaps it will do us good to be without female companionship for a while. Good for the soul and all that.”

“She fancies you, Rex,” Lord Pelham said. “She could hardly coax her eyes to turn in your direction, whereas she grinned and chatted with Nat and me as if we were her brothers. Now, that I resent. You did not crack a smile. The question is—do you want her or not? I would hate to see the only looker in this part of the world go to waste because Nat and I are too polite to step in on your territory.”

The viscount snorted.

“I believe,” Mr. Gascoigne said, “Rex must have had his face slapped the evening before last. Figuratively speaking even if not literally. You did pursue her during the evening of the walk, I presume? Were you quite gauche, Rex? Did you offer her carte blanche without even a day or two for maneuvering or courtship? We will have to give you some lessons in seduction, old chap. One does not step up to a virtuous country widow, tap her on the shoulder, and ask her if she would care to slip between the sheets with one. Is that what you did?”

“Go to hell,” Lord Rawleigh said.

“That is what he did, Ede,” Mr. Gascoigne said.

“It is no wonder he did not smile at her this morning and she could scarce look at him,” Lord Pelham said. “And is this our friend, the master seducer of Spanish beauties all those years we were in the Peninsula, Nat? It makes one shudder, does it not, to realize how fast a man can backslide from lack of practice.”

“Perhaps,” Mr. Gascoigne said, “I will try my hand at her and see if I have any better results. Hard luck, Rex, old boy, but you seem to have lost your chance.”

They were both grinning like hyenas and having a grand old time at his expense, Lord Rawleigh knew. He knew equally that if he wanted the teasing to stop, he must join in and give as good as he was getting. He could not do it. He growled instead.

“Hands off, Nat,” he said.

Mr. Gascoigne shot both hands into the air as if someone had just dug a pistol against his spine.

“She is a lady,” the viscount said. “She is not someone we take turns at seducing.”

“Good Lord,” Mr. Gascoigne said, “I do believe he is smitten, Ede.”

“I do believe you are right, Nat,” Lord Pelham said. “Interesting. Very interesting. And the death knell for your hopes and mine.”

Very often the three of them—and Ken too when he was with them—could hold lengthy and intelligent conversations on topics of importance. That was why they were friends. Often too they could exchange light banter and keep one another’s spirits up. That ability had been invaluable during the long years they had spent in Portugal and Spain and again in Belgium. They could be serious together and lighthearted together. They could fight wars together and stare death in the face together.

But sometimes, just sometimes, one of them could be out of tune with the others. Sometimes one of them could tell the others to go to hell and mean it.

She was not a topic of light banter.

And yet if he could not pick up the mood of the conversation, they would never leave him alone. Or her.

They had turned onto the driveway on their way back to the stables and the house. Probably there would be a few others up by now and ready for breakfast. Clarissa had planned an excursion for the afternoon to Pinewood Castle five miles distant, weather permitting. Clearly weather was going to permit. He was going to be expected to escort Ellen Hudson. Probably something would have been arranged for this morning also to somehow throw them together.

He drew his horse to a halt suddenly. “You two ride on,” he said, making his tone deliberately light. “I would hate to be a distraction to the two of you when you are so deep in mourning.”

They both looked at him and at each other in some surprise and the teasing light died from their eyes. One thing they had learned over the

years of their friendship was sensitivity to one another’s moods. They might not realize immediately that one of the others was not sharing the mood of the group, but as soon as they did, they were immediately sympathetic.

“And you need to be alone,” Nat said. “Fair enough, Rex.”

“We will see you back at the house,” Eden said.

Not a word about believing he was going to ride back to find Catherine Winters. Not a suggestion of a teasing gleam in their eyes. He could not quite understand why he could not himself see the fun of the situation. After all, he had been rejected before. They all had. And they had all usually been able to laugh at their own expense as well as at one another. None of them was infallibly irresistible to the fair sex, after all.

He wheeled his horse without a word and made his way back down the drive. He might have pretended to have an errand in the village, but it was rather early for that. Besides, they would have known that he lied. He turned away from the village when he reached the bottom of the drive and rode back along the lane they had ridden just a few minutes before. He did not hurry. He hoped that enough time had elapsed that she would be gone without a trace. Not that there were many byways along which she might have been lost to sight. And he knew that her dog would have slowed her down since she did not keep him on a leash and he liked to wander and explore as they walked.

He hoped that he would not be able to catch up to her. Even so, he was disappointed when it seemed that she had indeed disappeared from sight. After riding for a few minutes, he could see no sign of her and yet he could see for some distance ahead. He soon realized where she must have gone, though. One of the side gates into the park suddenly came into view. It was closed, but then, she would have shut it after her to keep the deer inside. He tried the gate. It opened easily. It was obviously in frequent use. He maneuvered his horse around it and went inside.

There were ancient trees along this border of the park. It had been a favorite childhood playground. Even the smell of it was familiar and the shade and the silence. He dismounted and led his horse by the reins. Perhaps she had not come this way after all. But even if she had not, he would continue on his way and return home by this route. He had always liked trees. For some reason they could always be relied upon to bring a sense of peace.

And then he heard the snapping of twigs and the little brown-and-white terrier came loping along and set its front paws up against his legs. It wagged its tail. He must have made a friend, the viscount thought wryly. It did not even bark.

“Get down, sir,” he instructed the dog. “I do not appreciate having paw marks either on my boots or on my pantaloons.”

The dog licked at his hand. He had noticed before that the terrier would never win any prizes for obedience. She had clearly spoiled it.

“Toby, where are you?” he heard her call. “Toby?”

And then, while he was in the process of taking two paws in his hands and setting them on the ground, she came into sight. She stopped and looked at him, and he looked back. This had been foolishness, he thought. Why had he done it? She was a virtuous woman and he wanted nothing to do with virtuous women. Not in a one-on-one situation, anyway.

And what had happened to yesterday afternoon’s resolve?

She looked beyond him, as if expecting to see Nat and Eden, and then back. She said nothing.

“I, after all, am on my brother’s land,” he said. “What is your excuse?”

Her chin came up. “Mr. Adams has opened the park to the people from the village,” she said. “But I am on my way back to the gate. It is time we went home.”

“Walk back through the trees,” he said. “You can get from here all the way to the postern door and avoid the public path and the village. It is a much more pleasant route. I will show you the way.”

“I know it, thank you,” she said.

He should let it go at that. Walking back through the trees with her, leading his horse and waiting for her dog to explore every tree, would take at least half an hour. Quite alone with her among the trees. Claude would have his head.

He smiled at her. “Then let me accompany you?” he asked. “You are quite safe with me. I do not indulge in seductions this early in the morning.”

She blushed and he held her eyes with his, still smiling, pulling gently on that invisible thread between them.

“I can hardly forbid you,” she said, “when I am the trespasser and you are the guest.”

But she had not said any more about going back through the gate onto the road, he noticed.

They walked side by side, not touching. Yet he felt quite breathlessly aware of her.

“The primroses are all in bloom,” he said. “The daffodils will be out soon. Is spring your favorite time of the year, as it is mine?”

“Yes,” she said. “New birth. New hope. The promise of summertime ahead. Yes, it is my favorite time of year, even though my garden is not as full of color as it will be later.”

New hope. He wondered what her hopes were, what her dreams were. Did she have any of either? Or did she live such a placid and contented existence that she needed nothing else?

“New hope,” he said. “What do you hope for? Anything in particular?”

She was gazing ahead, he saw when he glanced down at her. Her eyes looked luminous and he knew the answer to one of his silent questions. There was wistfulness in her gaze, longing.

“Contentment,” she said. “Peace.”

“And do you have neither that you must hope for them?” he asked.

“I have both.” She glanced quickly up at him. “I want to keep them. They are fragile, you know. As fragile as happily-ever-afters. They are no absolute state that one attains and then keeps forever and ever. I wish they were.”

He had disturbed her peace. There was no accusation in her voice, but he knew it was so. And happily-ever-afters? Had she discovered with the death of a husband that there was no such thing? As he had discovered it with the fickleness of a betrothed?

“And you?” She looked up at him more steadily. “What are your hopes?”

He shrugged. What did he hope for? What did he dream of? Nothing? It was a disturbing thought but perhaps a true one. Only when one hoped for nothing and dreamed of nothing could one keep control of one’s own life. Dreams usually involved other people and other people could never be depended upon not to let one down, not to hurt one.

“I do not dabble in dreams,” he said. “I live and enjoy each day as it comes. In dreaming of the future one is wasting the present.”

“A common belief.” She smiled. “But one impossible to live up to, I believe. I think we all dream. How else can life be made bearable at times?”

“Has life sometimes been unbearable to you, then?” he asked. He wondered if her life really was contented. She had been living here for five years. She had been widowed for at least that long. How old was she? In her mid-twenties at a guess. From the age of twenty or so, then, she had lived alone. Was it really possible that she was contented with such an existence? Of course, it was possible that her marriage had been insupportable to her and the freedom of widowhood seemed a paradise in contrast.

“Life is unbearable to all of us at times,” she said. “No one is fortunate enough to escape all of life’s darkness, I believe.”

They had reached the river, which flowed through the wood and on out of the park to skirt behind the village. It gurgled downhill at this particular point, over stones and under an arched stone bridge with balustrades either side that they had used to balance on as children, arms outstretched.

“If ever you want peace,” he said, coming to a stop in the middle of the bridge and resting his arms along the top of the wall, “this is the place. There is nothing as soothing as the sight and sound of flowing water, especially when the light falling on it is filtered through the branches of trees.” He let his horse wande

r to the other side to graze on the grass of the bank.

She stopped beside him and looked down into the water. Her dog ran on ahead.

“I have spent many idle minutes standing just here,” she said. Perhaps she did not realize that the tone of wistfulness in her voice said more than her actual words expressed. It told him that she agreed with him and that there had been many occasions when she had needed to seek out peace.

He looked down at her, slim and dark and beautiful beside him. Her fingertips, in kid gloves, were resting on the edge of the balustrade. If only his calculations at the start had been correct, he thought, he would have known her quite intimately by now. He would know what that slender, shapely body felt like beneath his hands and against his own body. He would know how soft and warm and welcoming she was in her depths. He would know if she loved with cool competence or with hot passion. He would know if the first could be converted to the second.

He would wager that it could.

He wondered if once or twice would have satisfied him. Would he be hot for her still, as he was now? Or would he—as he usually was with women—be satisfied once he had known all there was to know? Would he have lost interest and not even have pursued her this morning for this unwise walk through the woods with her?

He could not know. He probably would never know.

He did not realize that he had been standing staring silently down at her until she looked up at him, awareness in her face and in her eyes.

He reached for something to say to her but could think of nothing. She opened her mouth as if to say something, but closed it again and looked back into the water. He wondered afterward why he did not merely straighten up and suggest that they continue on their way. He wondered why she did not think of the same way of defusing the tension of the moment.

But neither of them thought of it.

He leaned sideways and down, turning his head and finding her mouth with his own. He parted his lips in order to taste her. Her lips trembled quite noticeably before returning the pressure of his. He did not touch her anywhere else. Neither of them turned.