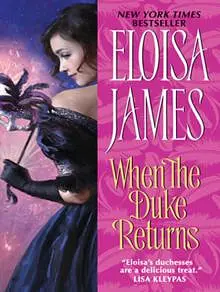

by Eloisa James

He could do without her.

It would ruin the quality and calmness of his life to have Isidore Del’Fino as a wife. She had turned around and was now sitting down on a little sofa, pulling off her gloves. Her fingers were slender, beautiful, pink-tipped.

“Do you know,” he said, sitting down opposite her, “I think we should discuss the question of annulment.”

She gasped, her eyes flew to his, and one of her gloves dropped to the floor.

“You must have thought of it,” he said, more gently. He picked up her glove and dropped it back in her lap.

“Of course.”

“If you would like an annulment, I would not stand in your way.”

She blinked at him for a moment, and then said, “I don’t understand you.”

He didn’t understand himself. He’d been offered one of the most beautiful women on three continents, and he was throwing her away. But she was trouble. The skin prickling all over his body told him that…as much trouble as he’d ever encountered, and that included the crocodile who almost chewed off his toes.

“I know that I behaved in an extraordinarily ungracious way, wandering around foreign parts and not returning to consummate our marriage. The least I can do is offer you another option, should you wish to take it. My mother has made it vehemently clear that I am unfit to marry a proper gentlewoman.”

Her eyes rested on his trousers. He wasn’t wearing breeches. He didn’t mind baring his lower leg when he was running, but he simply couldn’t get used to slipping into stockings. His mother had shrieked, of course. Apparently no one wore trousers except for artisans and eccentrics.

He had replied with the obvious truth: it seemed that he was an eccentric.

“Eccentrics and robbers!” his mother had added. “Yet even they wear white trousers!”

“I am wearing a cravat,” he said to Isidore now.

He couldn’t read her face. She had obviously noted the fact that he wasn’t wearing hair powder or a wig. “I tried on a wig with three rows of little snail shells over the ear. I looked like a lunatic.”

There was just a suspicion of a smile at the corner of her mouth. If he could find rubies that color, he would…

“Do you wear color on your lips?” he asked.

She shot him a look. “Why? Are you averse to women wearing face paint?”

“No, why should I be?” he said, surprised.

She seemed to relax. “There are men who consider themselves an apt judge of what a woman should or shouldn’t wear on her face.”

“I’m hardly the one to complain,” Simeon said, “given as I do not conform to all the customs of an English gentleman.”

“Obviously.”

“My mother tells me that I greatly underestimated your complaint regarding Nerot’s Hotel and that, in fact, ladies stay in such establishments only while traveling outside London. I had no idea from your protest that the experience was prohibited for women.”

“Is it my fault, then? I should have been more vehement?”

Simeon opened his mouth. Paused. “I should have listened to you?” he suggested.

There was a hint of a smile on her lips. “You must have worn a cravat at Eton.”

“Of course I did. But that feels like a lifetime ago. I am who I am because of the places I have been. And Eton is just a tiny kernel of my past. I’m fond of English seasons. There were times in the midst of the desert when I almost cried to remember how beautiful our rain can be. But the core of me was shaped by the deserts of Abyssinia, by the sands of India.”

She sighed.

“I know,” he said, nodding. “That’s why I thought it was better to bring up the question of annulment rather than let it fester silently between us.”

“Why don’t you wish to marry me?” she asked bluntly, looking up at him.

He opened his mouth but she raised her hand. “Please don’t tell me once again that you are offering me an annulment for my sake. I know precisely the weight you put on my opinion; it was eloquently expressed by your absence in the past years.”

He deserved that. And she deserved the truth.

“I am beautiful,” she added with a pugnacious kind of honesty that suggested it was second nature to her. “I am a virgin. And we are married. So why would you wish to annul that ceremony?”

“The desert changed me.”

She waited, and he had the feeling that it was only by a masterful effort of self-control that she didn’t curl her lip. Well, it did sound insane. Put that together with his virginity…“I met a great teacher named Valamksepa, when I first traveled to India. He taught me a great deal about what it means to be a man.”

“Ah,” she said. “A man is obviously not defined by his wig or his legs. So do tell me, what is the measure of a man?”

Her voice was calm, but underneath were banked fires. He was right to annul the marriage.

“A man is measured by his ability to control himself,” he said, not allowing the scorn in her eyes to shake him. “I wish to be the sort of man who never falls prey to his baser emotions.”

She looked a little confused.

“Anger,” he told her. “Fear. Lust.”

“You want to avoid anger? How will you do that?”

He grinned. “Oh, I feel anger. The key is not to act on it, not to let it affect me or become an intrinsic part of my life.”

“But what has this to do with me?”

They’d reached the stickler. “I was taught,” he said carefully, “that a man comes to his life with many choices. Only a fool believes that fate gives him his hand of cards. We make decisions every day.”

“And?”

“Marriage is one of the most important. If you and I were to marry—really marry—I would want to undergo the marriage ceremony with you because it marks that important decision. It was something I should never have left to a proxy. Those are my vows to make and to keep.”

“Or not to make at all,” she said flatly. “The fact is, Cosway, that your decision after meeting me is not to make those vows. Am I right?”

“I—”

“You were initially happy to go through with a wedding ceremony,” she said. “Yet now you talk of annulment.”

She was playing with her glove again, pulling the fingers straight. A flare of fire went up from his belly. That small hand was—his. His to unglove, his to kiss, his to…His.

He glanced down at his coat to make sure it was thoroughly buttoned. “You are not what I expected,” he said bluntly. “My mother sent me a miniature once we were married. That’s how I recognized you at Strange’s house.”

“I remember. I sat for it while I was still living with your mother.”

“You looked sweet and docile. Fragile, really.”

Isidore’s eyes narrowed.

She had suddenly realized precisely why her so-called husband had initiated talk of annulments. He didn’t think she was sweet or docile. And he was right.

“My parents had both died several months before the portrait was painted,” she pointed out. “Likely I was fragile. Am I to apologize that I have now recovered from that event?”

“Of course not. I was merely explaining my mistaken impression.”

Isidore just stopped herself from tossing her head like an offended barmaid. “During my brief time in your mother’s house, she continually expressed her doubt that I would develop the qualities of a good wife. I gather you agree.”

“I’m afraid that she turned her wish into reality.”

“What do you mean?”

“She’s written to me regularly over the years, far more so than you have, I might add.”

Her mouth did drop open and she leapt to her feet. “You dare to criticize me for not writing you!”

“I didn’t mean to criticize—” Simeon said, rising as well.

Isidore took a step toward him. “You? You who never wrote me even a line? You who sent the letters I did write you straight to your solicitors, sin

ce I received answers from them? You dare suggest I should have written you more frequently?”

There was a moment of silence. “I didn’t think of it in that fashion.”

“You didn’t think of it. You didn’t think of writing to your wife?”

“You’re not really my wife.”

With that, Isidore completely lost her temper. “I bloody well am your wife! I am the only wife you have, and let me tell you, annulment will not be an easy business. What kind of fool are you? When you agreed to that proxy marriage, you agreed to having a wife. I was there, even if you weren’t. The ceremony was binding!”

“I didn’t mean that.”

It only made her more furious that he showed no signs of getting angry himself. She took a deep breath. “Then what precisely did you mean?”

“I suppose I have a queer idea of marriage.”

“That goes without saying,” Isidore snapped.

“I’ve seen a great deal of marriage. And I’ve spent a great deal of time assessing which marriages are the most successful. It seems absurdly obtuse, but for some reason I thought I had one of those marriages.”

“You just said,” Isidore noted with exaggerated patience, “that we weren’t married at all. With whom did you have this perfect marriage?”

“Well, with you. Except it wasn’t really with you; I see that now. The combination of that miniature and my mother’s descriptions—”

“Just what did your mother say about me?” Isidore demanded.

He looked at her.

“You might as well tell me the worst.”

“She never said a bad thing about you.”

“Now I am surprised.”

“She painted you as the very image of a perfect English gentlewoman: sweet, docile, perfect in every way.”

Isidore gasped.

“You are particularly skilled with needlework, and sometimes stay up half the night stitching seams for the poor. But when you aren’t engaged in charitable activities, you knot silk laces that are as light as cobwebs.”

“What?” she said faintly, dropping back into her chair.

“Light as cobwebs,” Cosway repeated, reseating himself as well. “I remember actually considering whether I should request further details. I was establishing a weaving factory in India.”

“You were—what?”

“Weaving. You know, silks.”

“I thought you were wandering around the Nile.”

“Well, that too. But I’m afflicted by curiosity. I can’t go to a new place without wanting to figure out how things are made, and how they might be made better. That leads to shipping them here and there, generally back to England for sale.”

“You’re a merchant,” Isidore said flatly. “Does your mother know of this development?”

He thought about it. “I have no idea. I expect not.”

“I truly feel sorry for her. You do realize that I wasn’t even living with her during the time when she wrote all those letters describing my domestic virtues?”

“A revelation I find, sadly, unsurprising. I’m afraid my arrival has been a terrible shock to my mother. All the time she was sending me letters about my submissive, chaste wife—”

“I am chaste!” Isidore flashed.

He met her eyes. “I know that.”

A flare of heat went straight down her back to her legs. “So you thought I was a meek little Puritan—”

“Tame,” he said, nodding. There was an annoying hint of a smile in his eyes. “Meek and obedient.”

“Your mother has much to answer for.”

“I formed a picture of our marriage based on that wife.”

“Who doesn’t exist.”

He nodded, but his face sobered. “You’re obviously far more intelligent than the pliable woman my mother described, Isidore. So I have to tell you that from what I’ve seen in the world, the best marriages are those in which a man’s wife is—well, biddable.”

Isidore felt her temper rising again but pushed it down. What could she expect? He may not have the outward trappings of an English gentleman, but he was voicing what many a man believed.

“I agree,” she said. “Although I would broaden the category. Were I to choose my own spouse, for example, I would like him to be, shall we say, civilized?”

His teeth were very white against his golden skin when he smiled. “Meek and obedient, in other words?”

“Those are not popular words among men. But I could see myself with a husband who was more quiet than myself. I have—” she coughed “—a terrible temper.”

“No!”

“All this sarcasm can’t be good for you,” she said. “You told me in the carriage that you like your every utterance to be straightforward.”

He laughed. “I can see you riding roughshod over some poor devil of a husband.”

“I wouldn’t,” she said, stung. “We could simply discuss things together. And come to an agreement that didn’t involve my opinion losing ground to his simply because I was his wife.”

“That’s reasonable. But the truth of it is that you would smile at him, and crook your finger, and the man would come to you as tame as a lapdog.”

Isidore shook her head. “It’s not the sort of relationship you would understand.”

“I shall enjoy seeing you engage in it. If we annul our marriage and I can watch some other fellow experiencing it with you. Naturally I would repay your dowry with ample interest.”

So he didn’t want to come anywhere near her. Isidore was so stoked by rage that she could hardly speak. She was being rejected—rejected!— by her husband after waiting for him for years. She got up again and walked a few steps away, the better to regain control of her face.

“I think it’s important in any relationship that there be a clearly designated leader,” he was saying. “And I would rather be the leader in my own marriage.” Then he added: “If you don’t mind, Isidore, I won’t rise this time.”

Cosway would rather annul the marriage than marry her.

She waited for that news to sink in, but the only thing she could feel was the beating of her heart, anger and humiliation driving it to a rapid tattoo.

“As it happens,” she said, schooling her voice to calm indifference with every bit of strength she had, “Jemma gave me the direction of the Duke of Beaumont’s solicitor in the Inns of Court. I shall make inquiries as to how we go about an annulment.”

There was a flash of something in his eyes. What? Regret? Surely not. He sat there, looking calm and relaxed, like a king on his throne. He was throwing her away because she wasn’t a docile little seamstress, because she would make him angry.

Angry—and lustful. That was something to think about. She could unclothe herself right here, in the drawing room, and then he would have to marry her, but that would be cutting off her nose to spite her face. Why would she bind herself in marriage to a man like this? With these foolish ideas learned in the desert?

“Why don’t we make a trip there tomorrow afternoon?” he was asking now.

Isidore refused to allow his eagerness to visit the solicitor to throw her further into humiliation. He was a fool, and she’d known that since the moment she met him.

It would be better to annul the marriage.

She sat down opposite him, reasonably certain that her face showed nothing more than faint irritation. “I have an appointment at eleven tomorrow morning with a mantua-maker to discuss intimate attire.”

“Intimate what?”

“A nightdress for my wedding night,” she said crushingly.

“If we visit the solicitor first, I would be happy to accompany you to your appointment .”

Isidore narrowed her eyes, wondering about the look on her husband’s face. She was no expert, but it didn’t look like a man who was in control of his lust.

There were three things that no man was supposed to act on, weren’t there? Anger, lust…and an idea of marriage that included what?

Oh ye

s.

An intelligent woman within a ten-foot radius.

That must be where fear came in.

Chapter Eight

Gore House, Kensington

London Seat of the Duke of Beaumont

February 26, 1784

“Your Grace.”

Jemma, Duchess of Beaumont, looked up from her chess board. She had it set out in the library, in the hopes that her husband would come home from the House of Lords earlier than expected. “Yes, Fowle?”

“The Duke of Villiers has sent in his card.”

“Is he in his carriage?”

Fowle inclined his head.

“Do request his presence, if he can spare the time.”

Fowle paced from the library as majestically as he had entered. It was a sad fact, Jemma thought, that her butler resembled nothing so much as a plump village priest, and yet he clearly envisioned himself as a duke. Or perhaps even a king. There was a touch of noblesse oblige in the way he tolerated Jemma’s obsession with chess, for example.

Naturally, the Duke of Villiers made a grand entrance. He paused for a moment in the doorway, a vision in pale rose, with black-edged lace falling around his wrists and at his neck. Then he swept into a ducal bow such as Fowle could only dream of.

Jemma came to her feet feeling slightly amused and thoroughly delighted to see Villiers. She used to think that he had the coldest eyes of any man in the ton. And yet as she rose from a deep curtsy and took his hands, she revised her opinion. His eyes were black as the devil’s nightshirt, to quote her old nanny. And yet—

“I have missed you during my sojourn at Fonthill,” he said, raising her hand to his lips.

Not cold.

His thick hair was tied back with a rose ribbon. He looked pale but healthy, presumably recovered from the duel that nearly killed him a few months before. She felt a small pulse of guilt: the duel had been won by her brother, after which he summarily married Villiers’s fiancée. Much though Jemma loved her new sister-in-law, she wished that the relation could have been won without injuring her favorite chess partner.

“Come,” she said, leading him to the fire. “You’re still too thin, you know. Should you be upright?”