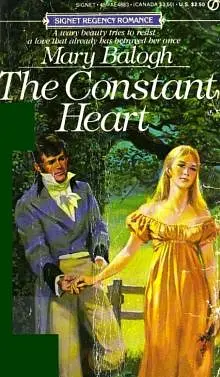

by Mary Balogh

"I wish I could bully you into a greater display of good manners, my girl," Christopher said as Rebecca clutched her arms harder in an agony of embarrassment. "I have no wish to coerce Miss Shaw into doing anything she does not desire to do."

"Oh," Harriet said. "You must come, Rebecca. You can be so stuffy sometimes, but you are only six-and-twenty. Really that is not so old. It will be a few years yet before you will be forced to sit with the chaperons."

"I really have not said I will not go," Rebecca said. "I have not even read my invitation yet, Harriet."

"I have no wish to coerce you," Christopher repeated, "but I do hope that you decide to come, Miss Shaw. Those of us who learned and performed the waltz here last week must show off our accomplishment at the ball."

His eyes, she saw when she looked directly at him over her shoulder, were positively dancing with merriment. Her stomach lurched. The old Christopher, some joke constantly on his lips.

"Go, Miss Shaw," he said, "before your hands and face match the blue of your dress."

Chapter 7

Rebecca returned a card accepting her invitation to the Langbourne ball. She had dithered long over the decision. She did not like to think it was true that she was becoming stuffy, and of course it was not necessarily true merely because Harriet had said so. But Rebecca had the feeling that it would be very easy for her to cut off all ties with her own class. And she had no real desire to do so. As a girl she had always enjoyed a party or ball or picnic. Indeed, Mama and Papa had done so too.

And she needed friends. She liked the poorer people of the neighborhood and enjoyed their company. But she was well aware that there was an invisible barrier between her and them that would always prevent them from becoming truly her friends. Her birth and her education set her apart from them. On the other hand, the people of her own class frequently annoyed her with their seeming unawareness that people around them constantly suffered from their poverty. Yet these were her people, the ones with whom she felt she belonged.

As a younger woman, Rebecca had succeeded in dividing her time to her own satisfaction, enjoying the pleasures that social life had to offer, yet using the bulk of her time to minister to the needs of her father and his poorer parishioners. Looking back now, she could see that the change had come with her rejection by Christopher. Social activities without him had lost their appeal, while serving others had helped dull the pain of her loss. The passing of Papa had completed the process, and she had had little to do with the various activities of her class in the years since.

It had not been a conscious choice. She had never rejected invitations out of hand. She had always considered them. But more often than not, she had found an excuse for not attending that had always sounded quite convincing to her. Yes, Harriet was right, she had decided at last. She had become staid, something of a killjoy. She would go to the ball, which was generally accepted as the most glittering event that the year had to offer in this part of the world.

Yet the decision had not been as easy as these thoughts might have made it. Christopher would be there, and he had expressed a hope that she would go too. Should she go and perhaps let him think that his words had prompted her into going? Should she allow him to think that his wishes still mattered to her? And did they? Could she convince herself that she was not now finding excuses to attend the ball because she did not want to admit to herself that it was the certainty of his presence that was drawing her there?

Philip was the one who finally helped her make up her mind. He had accepted his invitation, he told her when they were visiting the sick together one afternoon. It seemed only right that she should go too. Their relationship, which had seemed perfectly satisfactory to her in the months since they had become betrothed, suddenly seemed to be lifeless. Had things changed between them in the previous few weeks? Or had it always been like this, and she had only now become aware of the fact? Perhaps her memories of the way things had been with her and Christopher were making her realize the great contrast with her present engagement.

Yet she must never complain. Love and passion were unreliable. They did not stand the test of time. Her relationship with Philip was undemonstrative, but in that fact lay its very strength. They shared similar ideas, beliefs, and values. They were involved in similar work. They respected each other. She need never fear that he would abandon her as Christopher had done when he had tired of his love for her.

Thinking about Philip made Rebecca feel guilty. She did not believe that she had behaved differently toward him in the last few weeks, but she knew that she had felt differently. She had been feeling dissatisfaction. She had noticed things about him that really did not matter at all. He was not a lighthearted man; he did not smile or laugh a great deal; he did not spend time on activities or conversation that he felt did not relate to his work. Even attending functions like the Sinclair picnic and the Langbourne ball were duty to him.

But truly these things were unimportant. Philip was a man of great integrity, and he really did cater to the needs of his flock without regard to his own comfort. On the afternoon when he told her of his acceptance of his invitation to the ball, for example, he had also told her of a new scheme of his. It was to visit the elderly and the sick- people who were confined a great deal to their homes-in order to read to them. Some of them had never heard a story, except perhaps the type of folktale that parents told their children. Surely it would help relieve the tedium of their days if he could read to them for an hour a few times a week from the great works of literature.

It was a simple enough idea, yet it was typical of Philip. He listed several people whom he intended to serve in this way. And Rebecca, doing quick calculations in her head, realized that this new project would add many hours to his work schedule each week, and miles of extra travel.

She must return her thoughts to him. She must concentrate all her attention on his good qualities and ignore those things about him that were less attractive. After all, no one was perfect, and she hated to think of what would happen if he started to dwell upon her weaknesses. So she would attend the ball and devote herself to showing her esteem for him during the evening. It did not matter that Christopher would be there too. She must get used to seeing him without being affected by his presence. After all, he was the son of the Sinclairs. She was likely to see a great deal of him in the coming years.

She hoped to avoid meeting the visitors at the Sinclair home during the week before the ball, but it was not to be. The chilly, windy weather continued and seemed very likely to turn to rain as Rebecca walked home from school one afternoon. Her shawl did little to keep the wind from cutting through to the very marrow of her bones. Several times she felt an isolated spot of rain, and there was still almost half a mile to walk before she could turn off onto the shortcut through the pasture. For once she was definitely sorry that she had not accepted Uncle.Humphrey's offer of the gig. He had been quite insistent that morning. She bent her head to the wind.

This time she did not hear the horses come up behind her until they were almost level with her. When she did hear them, she looked back anxiously, and sure enough, there they were again, Mr. Carver in the lead, and Christopher slightly behind him.

"Miss Shaw," Lucas Carver said in his usual amiable way. "You look like a damsel in distress, if ever I saw one. It's a pity damsels are not attacked by dragons in these days. The fire from its nostrils might warm us all up." He shook with mirth at his own joke.

"Everett should have brought you home," Christopher said. "Does he not have a conveyance?" His face and voice were quite severe. He also looked quite snug in his greatcoat.

"Philip was from home this afternoon," Rebecca said curtly. "He is a busy man."

"Too busy to look after the welfare of his betrothed?" Christopher asked, one eyebrow raised.

Had Mr. Carver not been there, Rebecca would have answered with the anger she felt. As it was, she merely stared back, tight-lipped. "If you will excuse me," she said, "I shall continue

on my way. I fear the rain is about to start in earnest." She held out a hand and looked up to fee heavy clouds overhead.

"It is too far for you to walk in such weather," he said. "Come, take my hand and step on my boot. I shall pull you up and take you home."

"No, really," Rebecca said, pulling her shawl closer around her and stepping back, "I shall be quite warm once I start walking again."

But he would not let her pull her eyes away from his. "Come," was all he said, his hand still outstretched.

If only Mr. Carver were not there! Rebecca could feel her face burning, cold or no cold. She stepped forward again and placed her hand timidly in his. She raised her skirt with the other hand and placed a foot on his Hessian boot. He was very strong, she thought through the confusion of her mind. Beyond those two actions, she seemed to make no effort at all, yet a mere few seconds later she was seated sideways on the horse in front of his saddle, one of his arms firmly holding her in place.

He prodded the horse into motion. Rebecca was utterly mortified. She tried to sit upright, away from him, but it was impossible to do so. The only way she could keep from losing her balance was to lean sideways, one shoulder and arm pressed firmly against his chest. His arm stayed around her.

"Wish now that I had thought of playing Sir Galahad," Mr. Carver said. "Only trouble is, ma'am, that m'horse would probably sag in the middle if it were forced to bear one ounce more than my weight." He laughed as he rode on slightly ahead of his companion on the narrow country lane.

When they came to the point in the road at which it branched in two, one fork leading to the Sinclair home and the other to Limeglade, Christopher spoke again.

"You go on home, Luke," he said. "I shall take Miss Shaw home and be back in no time at all. Tell Mama to keep the tea hot for me."

Rebecca felt utterly dismayed. She had assumed that both men would ride to Limeglade with her, though now she thought of it, of course, it made no sense at all for both of them to ride out of their way.

"Right," Mr. Carver said. He touched his hat with his whip. "Pleased to have met you, Miss Shaw. Glad one of us could be of service to you. Looks as if the rain is going to hold off awhile longer. But very cold." He hunched his shoulders and turned his horse into the lane that led to his destination.

"Mr. Carver is right," Rebecca said hesitantly. "It is not going to rain yet after all. I could walk from here, Christopher, really I could. You need not ride out of your way."

He looked down at her. "You are just about blue with the cold," he said. "I thought you had more sense, Becky. You were too proud to borrow a vehicle, I suppose."

Rebecca would have replied, but she was suddenly made speechless as he transferred his horse's reins to the hand that also held her and with the other hand began to unbutton his greatcoat. A few seconds later she found herself enveloped in its warm folds and pulled even closer against him. She dared not trust her voice to say anything. All her efforts had to be used to keep her head from contact with his body. Even that battle was lost after a few minutes, though. The strain on the muscles of her neck was too great; she was forced to rest her head against his shoulder.

They rode in silence for the mile that still lay ahead before they came to the gates that opened onto the drive leading to the house. For all her resolves of the previous few days, Rebecca found that she could not prevent herself from feeling an overwhelming sadness. It was so long since she had been close to him like this. And he was different. He had lost his boyish leanness. His body had hardened into well-muscled maturity. Yet it could be no one else but him. There was a certain feeling about being with Christopher that she had forgotten, a feeling of safe-ness, of rigntness. And there was a certain smell about him, of soap, cologne, leather, perhaps-she was not quite sure what. That too she had forgotten until now.

She wanted to do nothing more than turn her face into his neckcloth, wrap her arms around his waist, and cry. Instead, she held herself rigidly still, trying to fight her treacherous body, trying to think of Philip.

"You can set me down here," she said at last when they were one bend away from the house. She did not wish him to take her right up to the door. She would be obliged then to invite him inside. And she did not wish the others to know that she had ridden with him for a few miles. Uncle Humphrey, or even Harriet, might remember something from the past and tease her about it.

She was relieved when Christopher drew his horse to a halt. For reasons of his own he must agree with her. He did not want Harriet, perhaps, to know that he had been with her.

"Very well," he said. "You should not get very cold between here and the house. Tomorrow, Becky, if you are to teach, will you please take one of your uncle's carriages? I imagine that this weather will persist for a few days yet."

He swung down from the saddle and reached up to lift her to the ground. It was really not his fault. Rebecca was honest enough to realize that afterward when she had run to her room and had had time to calm down enough to think rather than merely feel. It was her fault entirely. His own arms stayed quite firm. He did not intend that she touch him on the way down. It was her own arms that went suddenly weak at the elbows. She had put her hands on his shoulders to brace herself, but suddenly she lurched toward him so that she slid the whole agonizing length of his body between her high perch and the ground.

She sucked in a ragged breath of air and looked up into his face in dismay. "Christopher!" was all she could think of to say. Pretty stupid, as she admitted to herself later. Why say that?

"Becky!" He whispered her name.

It was those blue eyes that were really to blame, of course, but then, in all fairness, she had to admit that he was not really responsible for those. She could not look away from them even when they came closer. Finally, when she could focus no longer she had to close her eyes. But that did nothing to break the spell because by that time his mouth was on hers.

It was easy enough afterward to tell herself that she should immediately have pulled away and run for her life. The trouble was that one's mind did not work quite rationally when one was being kissed by the only man one had ever loved, and the man one had loved so totally that no one had ever been able to take his place.

She was inside his greatcoat again, the coat and his arms wrapped around her, her own hands splayed warmly over the silk shirt that covered his chest. (How had his jacket and waistcoat become unbuttoned?) And his mouth was opened over hers, his tongue pushing urgently beyond the barrier of her lips and teeth. She had forgotten-ah, yes, she had forgotten just how much he could stir her blood and make her ache with longing for him. She pressed against him, the coat and his arms quite unnecessary to hold her close. She wanted this to happen, had wanted it from that first moment of meeting him on the laneway home a couple of weeks before. She wanted him. She loved him. He was Christopher, and she did not care about anything else. She did not care.

He ended the kiss and looked down into her bewildered eyes. His own looked unnaturally bright. "Becky," he said very softly. "Becky, I am sorry. I am sorry about everything. But this especially. I have no right. I have caused enough havoc in your life, I believe. Please forgive me."

Rebecca looked back, wide-eyed now. He was the old Christopher, human and vulnerable. But, of course, he was not the old Christopher at all. And even that man had been a figment of her imagination.

And then, finally, too late, much too late, she turned and fled.

***

Rebecca was walking in Maude's formal garden the next afternoon, breathing in the heavy scent of the roses. It was a warm day and the sun shone from a clear sky, despite Christopher's prediction of the day before. For once she had stayed at home all day. It was not her regular day either for teaching or visiting the sick, and she had decided that she would not invent an extra errand.

She had been full of self-loathing since the afternoon before. How could she have allowed it to happen? Had she spent all those years working him out of her system and building up self-discipline

only to find that his mere appearance in her life again could bring all the barriers crashing down? Was she prepared to give up the secure and satisfying life that she had rebuilt from the ruins of her old life?

The answer to both questions certainly seemed to be yes. While she had been in his arms, his mouth on hers, she had surrendered completely to a physical longing that should have died years before. She had wanted him and given in to that desire. She had loved him.

Her self-loathing of the moment came entirely from the fact that she still could not convince herself that she had not meant it. She did love him. She always had, even when she had hated him most. She loved Christopher Sinclair, a man who had used her for his own satisfaction during a few months when he had had nothing else with which to amuse himself and had callously abandoned her as soon as he found someone who could cater more satisfactorily to his tastes. He had had the money and all the exciting life of town with which to entertain himself in the six and a half intervening years. And he still had the money.

Now he was back again, bored again, looking for a female with whom to carry on a flirtation. It did not seem to matter who she was. Harriet had set her cap at him, and he had lost no time in taking up the challenge. And he had certainly not hesitated to accept the open invitation she herself had seemed to offer the day before by allowing her body to sway against his.

She could remember one occasion when she really had deliberately done just that. They had been in the woods beyond the bridge, both perched in the low branches of a tree while they talked and laughed over some nonsense that she could not recall. When he had lifted her down, she quite deliberately and provocatively rubbed against him, giggling as she did so. She could even remember his words.

"Becky!" he had scolded. "Are you playing temptress?"

"Yes, definitely," she had admitted, grinning up at him. "You have not kissed me all afternoon."