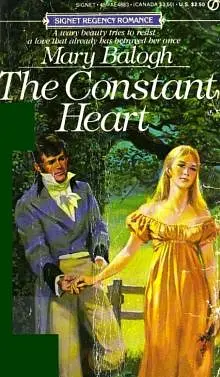

by Mary Balogh

There was much laughter as the dance proceeded. Mr. Bartlett and Harriet were the only couple who danced without apparent effort. But they were both experienced waltzers. Mr. Carver was an accomplished dancer, Rebecca found to her surprise. Despite his giant stature he moved with grace and provided a firm enough lead that she could follow him without tripping all over him. After the first minute she even found it easy to pick up the rhythm and to relax somewhat.

Julian and Ellen were having troubles. Scoldings from him and giggles from her finally erupted into a short quarrel when he trod heavily on her foot. Before the dance was half over, Primrose had replaced her sister in Julian's arms and they proceeded in relative peace.

Maude looked anxious, Rebecca noticed when she felt confident enough to glance around her from time to time. Her lips were moving; she was obviously still counting out her steps. Christopher was smiling down at her, his face softened again. When she glanced a second time, Maude was just stumbling at a turn, and he pulled her against his chest for a moment until she had regained her balance. He laughed into her dismayed face, but his own expression, was gentle. Rebecca swallowed and turned her head sharply back toward her own partner.

Philip joined her when the set came to an end. "I am sorry you had to be subjected to that indignity," he said, looking down at her with concern.

"Indignity?" she said. "You do not really think the dance improper, Philip, do you?"

"Perhaps not at a London ball," he said. "But I cannot think that it is right at a country home. For you, especially, Rebecca, it was an embarrassment. You are to be the wife of a vicar."

"I was not embarrassed, Philip," she said, touching his arm lightly. "We are among friends here."

"I blame Lady Holmes," he said. "She could quite easily have refused to allow the dance in her home. Yet again she has given in to the will of her stepdaughter, when she should be setting the example."

Poor Maude, Rebecca thought. She could do nothing right in Philip's eyes.

"Oh, that would be quite splendid!" Harriet was saying in a voice that was almost a shriek. "We have not had a picnic for an age. Not this summer at any rate."

"We thought the river would be a suitable site," Mrs. Sinclair said. "If the weather stays as it has been for more than a week now, we will be glad of the shade of the trees."

"Everyone must come," Ellen added, her voice as penetrating as Harriet's. "We decided that this afternoon. It will be no fun at all if anyone is absent. Lady Holmes, you will be there? And Mr. Bartlett?" She blushed as she turned to that gentleman.

He bowed and smiled at her. "How could I resist an invitation from such a charming young lady?" he said. "I shall assuredly attend your picnic, Miss Sinclair. And I am sure I speak for my sister too. Maude?"

"Lady Holmes and I shall both honor the occasion," the baron said, taking his snuffbox from a pocket and preparing to take a pinch. "There is a pathway that will take my carriage, is there not, Sinclair?"

"And will you be there, Reverend?" Mrs. Sinclair asked. "I know that the day after tomorrow is not a schoolday, and I am sure that the sick can spare you for one afternoon."

Philip hesitated. But Christopher replied before he had a chance to give an answer.

"Ellen has said that everyone must attend," he said. "And really we have decided that we will accept no refusals." The words were said with a smile. His intense blue eyes were directed, inexplicably, at Rebecca.

"Indeed," Philip said, "I was not about to refuse. You are all my parishioners, after all, even if only temporarily for some of you. The Lord's work can be done as well on a festive occasion as on a serious one."

"Miss Shaw, you will come too?" Primrose asked anxiously. "I wish to show you my new horse. Everyone else has seen him."

"Yes," Rebecca said, "I never could resist a picnic. Food always tastes so much more delicious out of doors. And I never could resist a horse, either, Primrose. I would love to see it." She glanced against her will at Christopher, but he was no longer looking at her. That momentary meeting of their eyes had been purely accidental.

She had not wanted to be drawn into the social events that she had known would develop out of his return home. She had thought to plead other more pressing activities during the days and tiredness during the evenings. But Philip had accepted this particular invitation. And she was betrothed to him. What could she do but accept too? Were this evening and the afternoon of the picnic to set a pattern? Had Philip been finally accepted as a member of the family circle although they were still only betrothed? It was a development that she had desired for a long time. But now surely was the wrong time for it to happen.

She was glad when this particular evening came to an end. She did not look forward to having to spend more time in the company of Christopher Sinclair. It was hard to believe that this man, so very self-assured and attractive yet so very aloof, was the same person as the boy she had played with and befriended, the young man to whom she had given her heart and all her confidences. She had felt so very comfortable with him for many years. Now it was an ordeal to meet his glance for a moment; it was an effort to avoid the embarrassment that a meeting of the eyes involved. She wished again with bitter passion that he had kept his promise never to return.

Chapter 5

"But which do you think I should wear, Rebecca?" Harriet asked. "If I wear.the yellow, I shall doubtless find that Primrose has chosen the same color. Yet it is more becoming on me, I think, than the blue. It shows my dark hair to more advantage. Do you not agree?"

Harriet was standing in her cousin's dressing room, her arms outstretched, a yellow muslin gown over one arm and a blue over the other. Her brow was drawn into a frown.

"I like both gowns," Rebecca said, considering. "The yellow is more vivid, but the blue is very delicate. If I were you, Harriet, I should wear the one that will be the most comfortable. It is like to be a hot day and there will be much walking and sitting on the grass."

Harriet lowered her arms and walked over to the stool that stood in front of the dressing table. She sat down. "My new straw bonnet is decorated with cornflowers," she said. "I suppose I should wear the blue. It will match his eyes." She sighed.

Rebecca went back to the task she had been busy with when Harriet had arrived, unannounced, without so much as knocking at the door-as usual. She was repairing the hem of the pink and blue floral-patterned cotton dress she planned to wear to the picnic that afternoon. She knew that Harriet's rare visits to her room generally lasted quite a while. They usually happened when the girl wanted to talk, yet found that neither her father nor Maude would do as listeners.

"Is he not gorgeously handsome, Rebecca?" she said, gazing dreamily in the direction of the window. "And so mature. It is a trial to live in such a retired corner of the country, where one rarely sees anyone worth seeing. I am so glad he came home. Do you expect he will stay long?"

"I really have no idea," Rebecca said. "But you are right. It is pleasant for you to have more young company. Mr. Bartlett, Mr. Carver, Mr. Sinclair: goodness, Harriet, we will hardly recognize our quiet neighborhood."

"Mr. Carver is quite insignificant," Harriet said disdainfully. "I cannot imagine why Mr. Sinclair associates with him. I suppose it is the other way around. Mr. Carver must feel that his own image is enhanced by his association with his friend."

"I would not underestimate Mr. Carver if I were you," Rebecca said hastily. "He1 is a well-bred and sensible young man, in my opinion. People should not always be judged by their appearance, Harriet."

"Mr. Bartlett is charming," the girl said, "though not exactly handsome, would you say, Rebecca? I could wish he were taller. But, of course, it does not matter. Mr. Sinclair is here now, and I mean to have him."

"Gracious!" Rebecca exclaimed, looking up from her task, her needle suspended in midair. "You have hardly even met him yet, Harriet. How can you be so sure of such a thing?"

"Oh," Harriet said, "it does not take more than one meeting to learn that a gentle

man is the most handsome man one has seen, Rebecca. I have always been determined to marry such a man. I want to be the envy of every other female when I marry."

"And nothing else matters?" Rebecca asked.

"Well, of course," her cousin replied, "if he is also rich and wellbred, then the connection becomes quite irresistible. Mr. Sinclair is all three. I can predict that Papa will be less than eager to allow the match. The Sinclairs are not our equal in rank, you know. But Mr. Sinclair has been away from here for years. No one looking at him now would know that his family was of such little consequence."

Rebecca kept her head lowered to her work. She found it appalling that Harriet could be so unconcerned about character «r companionship or any of the other requirements that she might look for in a good marriage. Good looks and money were the only criteria by which she would make her choice. In the coming days or weeks of Christopher's visit, she would probably remain oblivious to all the shortcomings of his character. Only after marriage, if she did achieve her aim, would she come face-to-face with the cold man who would marry for money and then ignore his wife while he carried on with his life of personal gratification.

In many ways Harriet deserved to be left alone to reap the rewards of her actions. Yet Rebecca hated to sit back and allow it to happen. She had known Harriet long enough to realize that her selfishness and thoughtlessness were more the result of a weak and indulgent upbringing than of a basic defect of character. The girl was capable of warm feelings and impulsive acts of generosity. If only she were fortunate enough to find the right husband, she might yet be shaped into a caring and responsible woman. Or so Rebecca liked to believe. Perhaps it was just an unlikely dream. But she must try if she could to discourage the flirtation that she was sure was about to develop between Harriet and Christopher.

Perhaps Mr. Bartlett could be persuaded to give Harriet some attention. There was even a faint chance that the girl would respond to his advances. She appeared not to dislike him, though his appearance admittedly showed to disadvantage when compared with Christopher's. It would be a great deal to ask of Maude's brother. He might well find it irksome to be forced into showing preference for one lady when he appeared to enjoy socializing with a wide range of people. She would not say anything to him immediately. But if she felt it necessary to divert Harriet's attention, then she would ask him. He appeared to care about the welfare of his sister's family.

Harriet had been sitting quietly for a while, staring off into space, one leg crossed over the other and swinging back and forth.

"He must be ready to take a new wife, do you not think, Rebecca?" she said. "He has been a widower for more than a year, and he must be feeling lonely. And this time, surely, he will be eager to take a bride of his own class and breeding. She was most shockingly vulgar, you know. And not at all pretty. Do you think I am pretty, Rebecca?"

"You know very well that you are," her cousin replied, looking up and smiling at her. "And very young, too, Harriet. I would not fix my choice with too much haste if I were you. You know that your papa has talked of taking you to London again for the Season next year. You will still be only nineteen."

"That is old!" Harriet said with some vehemence. "And I should not be a debutante. Everyone would wonder what was wrong with me that I had not found a husband during my first Season."

"Rather," Rebecca suggested, "they would see you as a discerning young lady who chose with care instead of snatching the first eligible male she cast her eyes on."

Harriet burst out laughing. "It is no use trying to argue with you, Rebecca," she said. "I should know by now. You always have an answer for everything. But it does not matter. I mean to have Mr. Christopher Sinclair. I shall take part in the Season next year as his wife. I can see us now. We will be the most handsome couple in the ton, I believe."

Rebecca smiled. "If you do not go and dress yourself in one of those gowns soon, Harriet," she suggested, "you are going to miss this picnic altogether. You know that it takes you at least twice as long as anyone else to get ready to go into company. And you will put your papa into a thundering mood if you are very late."

"Pooh," Harriet said, "he is always late himself." But she got to her feet and wandered in the direction of the door. "Do you think I should get married here where everyone we know will see me, or wait for a society wedding in London?" she asked.

"Harriet!" Rebecca exploded. "You are being quite ridiculous."

The girl grinned unexpectedly. "Mrs. Harriet Sinclair. Mrs. Christopher Sinclair. Do you not like the sound of it, Rebecca?"

"Harriet!"

No, Rebecca did not like the sound of it at all. In fact, she did not like many of the thoughts and feelings that had haunted her for the past several days. She had continued with her usual activities since her uncle and aunt's dinner party. She had taught; she had visited Mrs. Hopkins, who was confined with her eighth child and who had no one to help her with the other seven, all of whom were younger than twelve. Rebecca had tidied the house for her, washed and fed the children, and played with them until almost a whole day had passed without her realizing it.

On yet another day she had visited Cyril's home after school was over for the day. It had basically been a social call; she had taken with her some freshly baked muffins. But really she had been hoping to talk to the boy, to win his confidence away from the public setting of the schoolroom. He was a puny and timid twelve-year-old who did not respond well to attention in class, even if that attention were kindly meant.

She had been glad of her visit. Cyril, shy at first, even perhaps dismayed to see her, finally brought forward a rough wooden bench mat he had carpentered himself. It was for his mother to rest her feet on during the evenings while she was doing the family darning, he explained. And Rebecca found that she was able to direct the conversation toward his problems at school.

"I could read for sure, maybe, miss," he had said apologetically, "if the words would just stand still."

"Stand still?" she prompted gently.

"The other boys don't notice, miss," he said, "but them words dance about too quick for me."

"Do they, Cyril?" she asked, her attention focused fully on him. "Are all the books the same? Are some easier than others?"

"Them ones with the letters and pictures is easy," he said after thinking for a moment. "The letters is too big to move around. But in them other books, when the letters is squashed into words, they chases one another all over the paper."

Rebecca smiled. "I shall see if I can find you a book in which the words are large, Cyril," she said. "Then I wager you will read as well as any of us."

"Aw, miss," he had said, "I'm just dumb, like the reverend says."

Rebecca leaned forward and smiled at him. "I am going to prove both of you wrong, Cyril," she said.

It was true that in the day since that visit Rebecca's mind had been much preoccupied with the new problem she had discovered with the solving of the old one. Cyril obviously had very poor eyesight. She did not know why the truth had not struck her earlier. It was easy now to recall that the boy always held his book unnaturally close to his face. She had scolded him for doing so on more than one occasion. But it did not help to know the problem when the solution was not at all obvious. The boy needed eyeglasses. But how could poor farm laborers afford to buy eyeglasses for their son? And there was no money left in the school fund even if she could justify using it for such a purchase.

Really, though, Rebecca had to admit to her own chagrin, the bulk of her thoughts during those days had centered around Christopher and his unwelcome return to the neighborhood. She had always known deep down that she had never recovered fully from his defection. She had loved him for so long that he had become part of her very being. And it had all happened when she was young and impressionable. It had not been an adult experience that she might have shrugged off more easily. She had known as soon as she heard that he was coming home that old wounds would be opened, that she would not be immune to him.

She had not got over him at all, in fact, and she was disgusted with herself when forced to admit the truth. She had been aware of him in a very physical sense during every moment of that dinner party. And she was shocked and horrified to realize that the feeling she had had on seeing him with Harriet was not so much concern for the reputation of her cousin as jealousy. Pure and simple jealousy! She wanted him bending over her at the pianoforte, exercising that charm of conversation on her.

She almost hated herself. She certainly hated him for breaking his promise and coming back again. He had treated her so badly, abandoning her like that, breaking their engagement-even though it had been unofficial-after all that had happened between them in those months after they discovered their love for each other. Surely he could have done one honorable thing and stayed away from her for the rest of their lives.

She wished desperately that she did not have to attend this picnic. Yet for some reason Philip wanted to go. In fact, he had talked with something like enthusiasm about the occasion when she saw him two days before. And he seemed to be impressed with Christopher. He talked almost admiringly about his sincerity and friendliness. It was surprising, really. Philip was usually so sensitive to snobbery and hypocrisy. And surely he should have been able to see both in his new acquaintance.

Rebecca finally finished the repair to the hem of her dress. She would have finished long before had she not kept falling into a dream, she scolded herself. She got resolutely to her feet and began to change her clothes for the afternoon's outing. It was really useless telling herself that she did not wish to go and would not do so if it were not for Philip's wishes. Of course she wished to go. How dreadful it would be not to be there but to be wondering every moment what was happening, imagining with whom he was walking and talking.