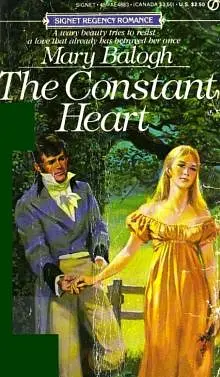

by Mary Balogh

She would just have to face the truth of the fact that his love for her had not been strong. It had been a pleasant flirtation, He had probably even intended to marry her. It might have been a reasonably successful marriage. But his visit to London had opened his eyes to the kind of life that he could live if he only had money. And suddenly it had all been within his grasp. Giving up the woman he had loved to a moderate degree must have seemed a small sacrifice to make for all the rewards of life with another woman who had the attraction of being rich. That must be it.

I loved you, Becky, with the whole of my being.

He had said that to her at the castle. Were those the words of a man who had loved only moderately?

My life came to an end the day I left you. 1 have lived in hell since then.

Were those the feelings of a man who did not know what deep emotion was?

Rebecca jerked the valise off the table as if by mistreating this inanimate object she might satisfy all her frustrated feelings, and made for the door. This was surely the worst summer of her life. She was very thankful that it was almost at an end. She made her way to the stables at the back of the parsonage, where her uncle's horse and gig had spent the day. She had been forced to bring the conveyance today because she had known that she would have a heavy load to carry home.

***

Harriet was almost back to normal again. Dr. Gamble had instructed that she was to keep her foot off the floor for another week, but there was no keeping her down once she could get fo her feet without screaming in agony. At first she took short walks around the garden, leaning heav-

ily on Mr. Bartlett's always available arm. But the day before she had crossed to the stables, had her mare saddled, and gone riding triumphantly off with her usual faithful companion.

Rebecca was surprised, in fact, to find her at home after the school had closed. She came marching into Rebecca's room almost on her heels. Rebecca could see immediately that she was in high dudgeon about something.

"Papa is just going to have to choose between me and that woman," she blurted without any preamble. "There is not room in this house for both of us."

These words were not a mystery to one who had lived in the bouse for several years. "What has poor Maude done now?" Rebecca asked mildly, untying the ribbons of her straw bonnet and tossing it onto the bed.

"Poor Maude!" said Harriet. "She is an upstart and a fortune hunter, that is what she is. And she thinks she can pose as my mama. The absurdity of it, Rebecca! She is only three years older than I am. It is even more ludicrous than your trying to tell me what to do. Thank goodness you never try, at least."

"If I do not, Harriet," Rebecca said, "it is because I know I should be only wasting my breath. Do sit down if you plan to stay. And not on that stool, please. I wish to sit before the mirror to brush my hair. What has Maude done?"

"She has asked Stanley to leave, that is what," Harriet said. “Her own brother! And when I expressly invited him to stay and told her so, she told me that she is mistress in this house and my wishes on the topic were not to be consulted. Imagine! This is my house, Rebecca, not hers. The nerve of the woman! And when I was going to go to Papa to tell him that Stanley was to stay because it is my wish, she forbade me to go to his room. My own papa! She said he is too sick to be pestered-pestered! Everyone knows that Papa is never sick. He merely pretends because he likes attention and does not like to exert himself to get up."

Harriet finally stopped for breath. Stanley, Rebecca thought. Was he Stanley now?"

"I am sorry if Maude has asked her brother to leave," she said. "But, you know, Harriet, she has every right to do so. He has been here for several weeks, and she is very busy now with your father. I am sure she is feeling weary and finding the burden of entertaining just too much to cope with."

"Stuff!" Harriet said. "How could Stanley be any trouble to Maude or anyone else? You speak as if she has to do all the cooking for him and the extra washing and everything else. She is afraid that I will marry him, that's what, Rebecca, and that I will have children. Then Papa will again love me more than he loves her-though I think he already does, anyway. I don't think Maude can have children. At least she has shown no sign of increasing since she has been married to Papa. Now she is jealous. She does not wish to see me married."

"Harriet," Rebecca said, removing several hairpins from her mouth in order to speak, "slow down. Surely there is no question of your marrying Mr. Bartlett anyway, is there?"

"And why not, pray?" Harriet asked tartly. "I am sure he is more of a gentleman than Mr. Christopher Sinclair or Julian or any of the other suitors I have had."

"Indeed," Rebecca said. "I agree that Mr. Bartlett has very superior manners and is excessively amiable. I have just been taken by surprise. I had not thought of him in terms of a suitor for you."

"You think him too poor, no doubt," Harriet said. "It is true he has little money and no prospects. And he does not try to hide the fact. And it is not his idea that we should be wed. He says it would not be the thing at all. But I do not care a fig about money, Rebecca. I have enough for both of us."

Rebecca removed the pins from her mouth again. She had not touched her hair with the brush since she had put them back there. "Harriet," she said faintly, "if Mr. Bartlett has not had the idea of marrying you, how did the subject come up between you?"

"Oh," Harriet said, "He said that it would be the dearest wish of his heart to offer for me, but he cannot. He is really a tragic figure, you know, Rebecca. He once loved another. But she died. And now I have helped him recover from his loss. He really is quite handsome, is he not, despite his red hair and his rather short stature?"

Rebecca was beginning to understand why Maude was trying to remove her brother from the house. It was true that he was an amiable man and that he would probably make Harriet a tolerable husband. He would be indulgent, anyway. But Uncle Humphrey would not see it as a good match. He expected greater things for his only daughter. Maude must be living in terror of his finding out about the budding romance and blaming her. It really was a pity, but Rebecca could sympathize.

"And is Mr. Bartlett going to leave?" she asked.

Harriet scowled. "He may stay until the day after the fair, according to her high and mighty ladyship," she said. "But I shall see Papa before then, never fear. I do not intend to be bossed around by that intruder."

Rebecca secretly thought that Lord Holmes would, for once, stand up to his daughter if he knew the truth of what was developing beneath his roof, but she held her counsel.

Harriet giggled unexpectedly. "We were out riding this afternoon," she said, "when we saw Mr. Carver again. He was riding to the village. He raised his hat and looked very stern. Stanley bowed, very civil, and I nodded my head, but neither one of us smiled. It was really very comical, Rebecca. He asked about my ankle and I said- very haughty-'Pray, sir, have you not been told by the Sinclairs, who have visited me every day since my accident' — I emphasized the every-'that I am now going along tolerably well? I am surprised at their silence, sir.' Then I turned and said, 'Come along, Stanley, the horses are getting skittish at the delay.' You should just have seen his face, Rebecca."

"Yes," her cousin replied, "I can just imagine, Harriet. I suppose you did not consider thanking Mr. Carver for the assistance he gave you at the castle?"

"Thanking him!" Harriet said. "That odious, pompous tyrant? Did you hear what he said? He said I deserved a thrashing! Any gentleman would have been all attention and solicitous concern. I might have been dead!"

"Precisely," Rebecca said. "And it would all have been your fault, Harriet."

Harriet fixed her cousin with a severe eye. "Sometimes, Rebecca," she said, "I think you are positively stuffy. You are actually taking the part of a man who can behave with such a want of conduct? I can just picture him thrashing a female, too. It would doubtless make him feel manly. He would find himself with a few bruises of his own if he ever tried to lay a hand on me, I can tell you."

"Well," Rebecca said soothingly, "I think you can rest assured, Harriet, that he never will. Mr. Carver is enough of a gentleman not to try to lay hands on any female who was not either his sister, hjs daughter, or his wife." She thought again of the reaction she had evoked quite unwittingly from Mr. Carver when she had said something quite similar to him a few days before and looked curiously at Harriet in the mirror.

Harriet, though, was not blushing and coughing at the thought. "His wife-ugh!" she said, and clutched her throat and stuck out her tongue.

***

Maude was quiet at the dinner table that evening. She was looking pale and weary, Rebecca thought. She was quite surprised, in fact, that her uncle's wife had put in an appearance at all downstairs.

"How is Uncle Humphrey?" she asked when she was alone with Maude before the meal. "Is he sleeping?"

"Yes, at present he is," Maude answered. "He really is not well, and the doctor told me today that he suspects a weak heart. Oh, Rebecca, and I have been so impatient wrth his ailments."

"Nonsense," Rebecca said, going to her and putting an arm around her shoulders. "You have been nothing but patience, Maude. You will have to be careful that you do not become sick too. You are looking very tired. Had you not better have some fresh air? Perhaps a walk afterwards? The evening air will be cool and very refreshing."

"How I would love that!" Maude said wistfully. "If his lordship is still asleep when dinner is over, perhaps I will walk, Rebecca, if you will join me. If he is awake, he will doubtless want me in attendance. Besides, he does not like me to walk in the evening air. He is afraid that I will take a chill."

She lapsed into silence again. It was altogether a strained meal. Harriet was showing silent displeasure to her stepmother, pointedly ignoring her and addressing the few remarks she did make to Mr. Bartlett or Rebecca. Mr. Bartlett himself did his best to charm everyone back into a good humor, but it was completely beyond his power to do so.

Lord Holmes was still asleep when Maude went up to his bedchamber to check on him. She left his valet in attendance and came back downstairs, a shawl around her shoulders, to claim her walk with Rebecca. They strolled south across the lawn and into the pasture.

Maude breathed deeply and lifted her face to the late evening sky. "Oh, Rebecca," she said, "you cannot know how good it feels to escape into the outdoors once in a while. How I envy you your life of activity and usefulness."

Rebecca bit her lip. "I certainly would not say your life is useless at the moment," she said. "I am sure you are bringing great comfort to Uncle Humphrey."

Maude sighed. "He will not let me out of his sight when he is awake," she said, "yet I cannot do anything right for him. If I plump up his pillows, I leave them lumpy; if I read to him, I read too quietly or too loudly. And now it seems that he really is ill. Poor Humphrey! Sometimes I wonder if I am of any use to him or anyone else in the world."

"Oh, please do not talk like that!" Rebecca said, distressed. "Indeed, at times it does seem that life is tedious and pointless, but those times always pass. You are of great value to me, Maude. I believe I would find life at my uncle's house less easy to support if it were not for your calm and sweet presence."

"How kind of you to say so," Maude said, flashing the other a grateful smile. "But I do know what you mean. I hate to criticize Harriet; she has many good qualities that I do not possess-vitality, strong will, determination. But she is very undisciplined. I am only three years older than she, Rebecca, and I have lived a sheltered existence. Yet even so, I know a great deal more about life than she, though she would never believe so. I think having Stanley as a brother has taught me many of the harsher truths of life."

"Harriet is selfish and she does not always display the greatest good sense," Rebecca agreed, "but I still hope that one day she will grow up and turn out not so badly after all."

"I have always believed so, too," Maude said, "and indeed I still hope so. But I do fear, Rebecca, that she will do something foolish that will blight the whole future course of her life."

"She told me this afternoon about your trying to separate her from your brother," Rebecca said gently. "Do you really believe it would be such an imprudent match, Maude?"

Maude shot her one penetrating glance and looked ahead again. "I find it hard to speak ill of my brother," she said, "but really he is not the man for Harriet."

"Just because he has no fortune and no prospects?" Rebecca asked. "Do those facts matter so much when he has qualities enough to compensate for the lack? Harriet does not need to marry for money. Indeed, I am convinced that she would be fortunate indeed to attract such an amiable husband. He seems to feel an affection for her."

"Stanley feels affection for no one but himself!" Maude said bitterly. "Nothing has ever mattered to him but the gratification of his own desires and the everlasting search for wealth and comfort."

"You surely cannot be serious," Rebecca said. "You are tired, Maude. You are perhaps afraid that Uncle Humphrey will be displeased with you if he learns of this attachment between Harriet and Mr. Bartlett. But you cannot really mean what you just said."

"Oh, can I not?" Maude said, her voice breathless. "I did not mean to say so much, Rebecca, but since I have begun, I might as well continue. Sometimes I feel so lonely having no one in whom to confide. Stanley is coldhearted and totally lacking in morals. He is a consummate actor, as you have seen, but I have known him all my life. And he has never been any different. We were not always poor. Papa was never wealthy, it is true, but there was always enough. There was money for Stanley to live in modest comfort all his life and money for a respectable dowry for me. Stanley gambled it all away within a year of leaving home, and Papa was foolish enough to pay all his debts rather than see him go to debtors' prison."

Rebecca stared incredulously at the hard profile of her companion, who was striding across the meadow with probably no idea of where she was going.

"He was always clever at seeming sincere," Maude continued. "He was always a great favorite with the ladies even when he was quite a young boy. He used that charm to try to attract a rich wife when there was no money left. He almost succeeded once, I believe, until he was cut out by someone else. Now he is after Harriet. He has been very clever. He has waited until it has become unlikely that I will ever bear an heir. Harriet would not be such an heiress, you see, if I had a son. But now he thinks it reasonably safe to put his plan into effect. I thought even Harriet would have had enough sense to discourage his suit, but she has begun to favor him, I think because she has been disappointed by Mr. Sinclair's lack of ardor."

Rebecca was silent. She did not know what to say. She could not doubt the truth of what Maude said. Mr. Bartlett was her brother, and Maude was not one to indulge in spite for no reason. Yet she found it almost impossible to adjust her mind to the new image of the charming and amiable gentleman she had known for several weeks. Mr. Carver, too, had called him a viper. Could it be possible that he had done so with good reason, and not merely in defense of his friend whose enemy Mr. Bartlett was?

"Fortunately," Maude said, slowing her pace and seeming to recollect herself somewhat, "his lordship has given me his support, though he does not know the truth about Stanley. Harriet went to see him before dinner while I was downstairs fetching his medicine. I was very vexed; I had forbidden her to worry her papa when he is so obviously unwell. But she gained nothing. When I came back into the room, he was telling her quite roundly that Stanley has been here long enough and that if I saw fit to tell him to pack his bags, then that is the way it must be. She was very chagrined, knowing that I was there to hear what he said. But I am relieved,Rebecca. In three days' time Stanley will be gone and Harriet will be safe from that peril, at least. Not much harm can come to her in the meantime, 1 believe."

"I am sure Harriet does not feel any deep attachment to Mr. Bartlett," Rebecca said. "Once he has gone, she will turn her attention to someone else, I am sure. She has always been the same, Maude. I am afraid consta

ncy is not one of her chief virtues. Please do not worry about the matter. Everything will turn out well. Uncle Humphrey will probably feel more himself in a day or two-indeed, I have never known him to miss the fair. He loves to present the prizes at the end of the day. And Harriet will soon have her head full of some new attraction. You will be free to concentrate on gaining back your health and spirits."

"Bless you," Maude said. "I do love you, Rebecca, and I shall miss you dreadfully when you are married and removed to the parsonage."

And quite inexplicably she stopped in the middle of the pasture, put her hands over her face, and burst into tears.

Chapter 14

The annual village fair really had far more to offer the people of the lower classes than the gentry. The games of skill, the races, the exhibitions of needlecraft and baking, the food stalls and tearoom, the stall that sold ribbons and cheap and garish baubles, the jugglers, the fortune-teller, and the dances around the maypole seemingly had nothing to attract the superior minds of the rich and educated. Yet for as far back as she could remember, Rebecca has always looked forward all spring and summer to this particular day.

And she was not alone. Uncle Humphrey and Aunt Sybil had always spent the better part of the day and the evening in the village, graciously bestowing nods and bows on lesser mortals and presenting the prizes at the end of the day. That description was unfair to Aunt Sybil, she admitted. Her aunt had never condescended. She had mingled with her husband's tenants and laborers with the greatest delight, as had Mama and Papa. And the Sinclairs were always there and all the other landowners for miles around. It was one of those occasions that was popular for no explainable reason.

Only twice could she remember the day being spoiled by rain. The first time she had been ten years old and had cried and cried, her nose pressed miserably against the window of her room in the parsonage, because she had new white gloves and would not be able to show them off to Christopher Sinclair-even then there had been Christopher. The other time was the summer after her unofficial betrothal came to an end, a summer when she had been so out of spirits that she really had not cared.