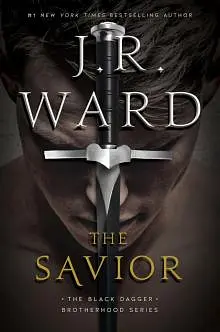

by J. R. Ward

But which had turned out to be anything save all that.

Lately, she had begun to feel that her grieving process had stalled because she was still in this house and at BioMed. She just didn’t know what to do about it.

“My mom died of cancer nine years ago.”

Sarah refocused on the agent and tried to remember what his comment was in reference to. Oh, right. Her job. “I lost mine from the disease sixteen years ago. When I was thirteen.”

“Is that why you got into what you’re doing?”

“Yes. Actually, both my parents died of cancer. Father pancreatic. Mother breast. So there’s an element of self-preservation to my research. I’m in an iffy gene pool.”

“That’s a lot of losses you’ve been through. Parents, future husband.”

She looked at her ragged nails. They were all chewed down to the quick. “Grief is a cold stream you acclimate to.”

“Still, your fiancé’s death must have hit you very hard.”

Sarah sat forward and looked the man in the eye. “Agent Manfred, why are you really here.”

“Just asking questions for background.”

“Your ID has you from Washington, D.C., not an Ithaca field office. It’s seventy-five degrees in this house because I’m always cold in the winter, and yet you’re not taking that windbreaker off while you’re drinking hot coffee. And Dr. McCaid died of a heart attack, or that’s what both the papers and the announcement at BioMed said. So I’m wondering why an imported special agent from the nation’s capital is showing up here wearing a wire and recording this conversation without my permission or knowledge while he asks questions about a man who supposedly died of natural causes as well as my fiancé who’s been dead for two years courtesy of the diabetes he suffered from since he was five years old.”

The agent put the mug down and his elbows on the table. No more smiling. No more pretext of chatting. No more roundabout.

“I want to know everything about the last twenty-four hours of your fiancé’s life, especially when you came home to find him on the floor of your bathroom two years ago. And then after that, we’ll see what else I need from you.”

Special Agent Manfred left one hour and twenty-six minutes later.

After Sarah closed her front door, she locked the dead bolt and went over to a window. Looking out through the blinds, she watched that gray sedan back out of her driveway, K-turn in the snowy street, and take off. She was aware of wanting to make sure the man actually left, although given what the government could do, any privacy she thought she had was no doubt illusory.

Returning to the kitchen, she poured the cold coffee out in the sink and wondered if he really did take the stuff black, or whether he had known he wouldn’t be drinking much of it and hadn’t wanted to waste her sugar and milk.

She ended up back at the table, sitting in the chair he’d been in, as if that would somehow help her divine the agent’s inner thoughts and knowledge. In classic interrogation form, he had given little away, only plying her with bits of information that proved he knew all the background, that he could trip her up, that he would know if she were lying to him. Other than those minor factual pinpoints on whatever map he was making, however, he had kept his figurative topography close to his chest.

Everything she had told him had been the truth. Gerry had been a Type 1 diabetic, and fairly good about managing his condition. He had been a regular tester and insulin administrator, but his diet could have been better and his meals were irregular. His only true failure, if it could be termed as such, was that he hadn’t bothered to get a pump. He rarely took breaks from his work and hadn’t wanted to waste the time having one “installed.”

Like his body was a house that needed an air conditioning unit or something.

Still, he’d managed his blood sugar levels pretty well. Sure there had been some rocky crashes, and she’d had to help him a couple of times, but on the whole, he’d been on top of his disease.

Until that one night. Almost two years ago.

Sarah closed her eyes and relived coming home with Indian food, the paper bags swinging from flimsy handles in her left hand as she’d struggled to open the front door with her key. It had been snowing and she hadn’t wanted to put the load down in the drifts as the garlic naan and the chicken curry had already lost enough BTUs on the trip across town. She herself had been on the hot and sweaty side, too, having been first to her spin class, the one she did every Saturday late afternoon, the one she’d wished she could make time for during the workweek, but never quite managed to leave the lab in time.

Six thirty p.m. Ish.

She could remember calling upstairs to him. He had stayed home to work because that was all he did, and although it felt wrong to admit now that he had passed, his constant focus on that project with Dr. McCaid had begun to wear on her. She’d always understood the devotion to the subject matter, to the science, to the possibility of discovery that, for both of them, was always just around the corner. But there had to be more to life than weekends that looked exactly like the M–F’s.

She’d called his name again as she walked into the kitchen. There had been annoyance that he didn’t answer. Anger that he probably hadn’t even heard her. Sadness that they were staying in, again, not because it was winter in Ithaca, but because there were no other plans. No friends. No family. No hobbies.

No movies. No eating out.

No holding hands.

No sex, really.

Of late, they had become just two people who had bought real estate together, the pair of them walking paths that had started out on the same trail, but had since diverged and become parallels with no intersection.

It had been four months until the wedding, and she could recall thinking of “postponing” the date. They could have pumped the brakes at that point and people could still have gotten their money back for airline tickets to, and hotel reservations in, Ithaca. Which had been the site of the ceremony and reception because Gerry hadn’t wanted to take the time off to travel to Germany, where his family was, and with both her parents gone and no siblings, Sarah had nothing left of where she’d grown up in Michigan.

As she’d put the bags of takeout on the counter, she had been struck with a profound immobility—and all because she needed a shower. Their bathroom was upstairs off the master bedroom, and to get to it, she would have to pass by his home office. Hear the ticking of his keyboard. See the glow of the computer monitors flashing molecular images. Feel the coldness of the shut-out that was somehow even more frigid than the weather outside of the house.

That night, she’d reached her adaptation threshold. So many times she’d walked by that makeshift office of his since they’d moved in. In the beginning, he had always looked over his shoulder as she had come up the stairs and he’d beckoned her in to show her things, ask her things. Over time, however, that had downshifted to a hello over his shoulder. And then a grunt. And then no response at all, even if she said his name when standing behind him.

Sometime around Thanksgiving, she’d taken to tiptoeing up the stairs so as not to disturb him, even though that was ridiculous because in his concentration, he was un-disturbable. But if she made no noise then he couldn’t be ignoring her, right? And she couldn’t be hurt and disappointed.

She couldn’t find herself in the unintended, unfathomable position of questioning their relationship after all their years of being together.

That night, as she had stood frozen at the kitchen counter, she’d been unable to face the reality of her deep unhappiness . . . yet she’d no longer been able to deny it, either. And that conundrum had trapped her between her desire for a hot shower after exercise and her head-in-the-sand position on the first floor.

Because if she had to walk by that office one more time and be ignored? She was going to have to do something about it.

Eventually, she’d forced herself to hit the stairs, a marching band of don’t-be-stupid’s drumming her ascent.

Her first clue that all was not well had been the empty swivel chair in front of his computers. Further, the room had been dark, although that was not all that unusual, and Gerry’s monitors had offered plenty of light with which to navigate around the sparsely furnished space. But it wasn’t like he got up all that often.

She’d told herself that he wasn’t where he should have been because nature had called and she promptly resented the hell out of him for his need to pee: Now, she was going to have to interact with him in the bathroom.

Which was going to make cramming her emotions back into the Don’t Touch Toy Box even harder.

Special Agent Manfred had gotten the death scene right. She’d found her fiancé sitting up on the tile against the Jacuzzi’s built-in base, his legs out straight, his hands curled up on his thighs, his MedicAlert bracelet loose on his right wrist. His head had lolled to one side and there was a clear insulin bottle and a needle next to him. His hair, or what was left of the Boris Becker blond strands, was messy, probably from a seizure, and there was drool down the front of his Dropkick Murphys concert shirt.

Rushing over. Crouching down. Begging, pleading, even as she had checked his jugular and found no pulse underneath cold skin.

In that moment of loss, she had forgiven him all transgressions, her anger disappearing as if never been, her frustrations and doubts gone the way of his life force.

To heaven. Assuming there was such a place.

Calling 911. Ambulance arriving. Death confirmed.

The body had been removed, but things were hazy at that point; she couldn’t remember whether it had been taken by the paramedics or the morgue or the coroner. . . . Similar to someone who had sustained a head injury, she had amnesia about that part, about other parts. She remembered clearly calling his parents, however, and breaking down the second she’d heard his mother’s accented voice. Crying. Weeping. Promises by his parents to be on the next trans-Atlantic flight, vows to be strong on her side.

No one to call for herself.

Cause of death was determined to be hypoglycemia. Insulin shock.

Gerry’s parents ended up taking his body back to Hamburg, Germany, so that he could be buried in the family cemetery, and justlikethat, Sarah had been left here in this little house in Ithaca with very little to remember her fiancé by. Gerry had been the opposite of a hoarder, and besides, his parents had taken most of his things with them. Oh, and BioMed had sent a representative to take the computer towers from his home office, only the monitors remaining.

After the death, she had closed the door to that room and not reopened it for a good year and a half. When she finally did venture across the threshold, chinks in the all-is-forgiven armor she’d girded herself with had appeared the instant she’d seen that desk and chair.

She’d shut things up again.

Remembering Gerry as anything other than a good, hardworking man had felt like a betrayal. Still did.

Sarah had been through this post-passing recasting of character before with her parents. There were different standards for the quick and the dead. Those who were alive were nuanced, a combination of good and bad traits, and as both full-color and three-dimensional, they were capable of disappointing you and uplifting you in turns. Once a loved one was gone, however, assuming you were essentially fond of them, she had found that the disappointments faded and only the love remained.

If only through force of will.

To focus on anything but the good times, especially when it came to Gerry, felt just plain wrong—especially given that she blamed herself for his death. On their second date, he had taught her how to identify the symptoms of insulin shock and use his glucagon kit. She had even had to mix the solution and inject it into his thigh on three different occasions while they’d been in Cambridge: His cousin Gunter’s wedding when he’d drunk too much and not eaten. Then when he’d tried to run that 5k. And finally after he’d taken a big dose of insulin in preparation for a Friendsgiving dinner and they’d gotten a flat tire on Storrow Drive.

If she hadn’t stood there in front of the goddamn Indian food in the kitchen and been angry at him, could she have saved him? There was a glucagon kit right there in the top drawer by the sink.

If she had gone right upstairs for her shower, could she have used it in time and then called 911?

The questions haunted her because her answer was always yes. Yes, she could have turned the insulin crash around. Yes, he’d still be alive. Yes, she was responsible for his death because she had been condemning him for loving his work and finding purpose in saving people’s lives.

Reopening her eyes, she looked over at the counter. She could remember, after the body was removed and the police and medics had left and the phone call to Germany made, she had told herself to eat something and shuffled toward the kitchen. The silence in the house had been so resonant that the screaming in her head felt like the kind of thing the neighbors could hear.

Entering the kitchen. Stopping dead. Seeing the two paper bags full of now utterly cold and congealed food.

Her first thought had been how foolish to worry about putting them briefly in the snow to unlock the door. They had been destined to lose their warmth.

Just like Gerry’s once vital body.

Weeping again. Shaking. Jelly legs going out from under her. She had hit the floor and cried until the doorbell had rung.

BioMed security. Two of them. Coming for the computers.

Returning to the present, Sarah shifted around and looked through the archway, past the living room, to her front door.

She had been honest with Agent Manfred. She had told him the whole story—well, minus the emotional bits like the stuff about calling Gerry’s parents and her Cold Indian Takeout Food Breakdown.

Also the part about her feeling responsible for the death—and that was not just because she didn’t want to share the intimate details of the loss with a stranger. Bottom line, it didn’t feel smart to even hint to a federal agent that she believed she might have played a role, however unintentionally, in the very thing Manfred had come to talk to her about.

Other than those two omissions, both of which were non-factual, she’d hid nothing about the natural death that had tragically occurred to a Type 1 diabetic after he had no doubt kept on his insulin schedule but forgotten to eat all day long.

Utterly heartbreaking, but a totally common, garden variety way for someone with Gerry’s condition to die.

Frowning, she thought about her statements to Manfred. Relating the this-then-that-after-which-this-other-thing-happened to the agent had been the first time she had relived Gerry’s death from start to finish. In the intervening two years, she’d had plenty of flashbacks, but they had been out of sequence, an unending supply of discordant, invasive snapshots unleashed by all manner of foreseeable and unforeseeable triggers.

But tonight had been her first full replay of the horror movie.

And that was why she now wondered, even though she had spent too many hours to count ruminating on the natural death of her fiancé . . .

. . . how it was that BioMed had known to come pick up those computers before she had told anyone at the company that Gerry was dead.

CHAPTER THREE

The Black Dagger Brotherhood Mansion

Caldwell, New York

Born in a bus station. Left for dead. Rescued from the human world by a stroke of luck.

If John Matthew’s life had been required to carry ID, some kind of laminated card detailing its vitals, those would be his birth date, height, and eye color.

Listed also would be mute and mated. The former didn’t really matter to him as he had never known speech. The latter was everything to him.

Without Xhex, even the war wouldn’t matter.

As he entered the King’s study—that pale blue French sanctuary which suited Wrath and the Black Dagger Brotherhood about as well as a ball gown on an alligator—he found the four walls and the silk furniture crowded with big bodies. They were all

there waiting for the King, these prime males of the species, these teachers and smart-asses, these fighters and lovers.

This was his family on such a deep level that he felt like he should caboose that particular f-word with “of origin.”

Not everyone was a Brother, however. Still, he and Blay fought side by side with them in the war against the Lessening Society, and so did Xcor and the Band of Bastards. There were also trainees in the field and females. And the team had a surgeon who was a human, for godsakes. And a doctor who was a ghost and an advisor that was the king of the symphaths and a therapist who had been taken out of time continuum by the Scribe Virgin.

This was the village that had sprung up under Darius’s old roof, all of them living here on this Adirondack mountain, mhis protecting them from intrusion, time’s passing marked by the collective purpose of eradicating the Omega’s lessers.

Squeezing past Butch and V, he zeroed in on a spot in the corner. He always hung back, even though nobody asked him to last-row-it.

Leaning against the wall, he adjusted his weapons. He had a belt with a matched pair of forties and six full clips around his hips. Under one arm, he had a long-bladed hunting knife, and on the other side, he had a length of chain on his shoulder. Before he went out into the field, he’d throw on a leather jacket, either the new one Xhex had just gotten him or the old one that was beat to shit, and the wardrobe addition was not because it was a howling winter’s night out there.

If there was one thing he’d learned in the war? Humans were like toddlers. If there was something that could kill them, they would beeline for that mortal event like the gunfight/knife fight/hand-to-hand was calling their name and promising free Starbucks.