“We’ve never been introduced,” Anna said. “I discussed the position with Mr. Hopple, and he had no qualms about me becoming the earl’s secretary.” At least Mr. Hopple hadn’t voiced any qualms, she added mentally.

The cook grunted without looking up. “That’s just as well.” She rapidly pinched off walnut-sized bits of dough and rolled them into balls. A pile formed. “Bertha, fetch me that tray.”

The scullery maid brought over a cast-iron tray and lined up the balls on it in rows. “Gives me the chilly trembles, he does, when he shouts,” she whispered.

The cook cast a jaundiced eye on the maid. “The sound of hoot owls gives you the chilly trembles. The earl’s a fine gentleman. Pays us all a decent wage and gives us regular days off, he does.”

Bertha bit her lower lip as she carefully positioned each ball. “He’s got a terrible sharp tongue. Perhaps that’s why Mr. Tootleham left so—” She seemed to realize the cook was glaring at her and abruptly shut her mouth.

Mr. Hopple’s entrance broke the awkward silence. He wore an alarming violet waistcoat, embroidered all over with scarlet cherries.

“Good morning, good morning, Mrs. Wren.” He darted a glance at the watching cook and scullery maid and lowered his voice. “Are you quite sure, er, about this?”

“Of course, Mr. Hopple.” Anna smiled at the steward in what she hoped was a confident manner. “I am looking forward to making the acquaintance of the earl.”

She heard the cook humph behind her.

“Ah.” Mr. Hopple coughed. “As to that, the earl has journeyed to London on business. He often spends his time there, you know,” he said in a confiding tone. “Meeting with other learned gentlemen. The earl is quite an authority on agricultural matters.”

Disappointment shot through her. “Shall I wait for his return?” she asked.

“No, no. No need,” Mr. Hopple said. “His lordship left some papers for you to transcribe in the library. I’ll just show you there, shall I?”

Anna nodded and followed the steward out of the kitchen and up the back stairs into the main hallway. The floor was pink and black marble parquet, beautifully inlaid, although a bit hard to see in the dim light. They came to the main entrance, and she stared at the grand staircase. Good Lord, it was huge. The stairs led up to a landing the size of her kitchen and then parted into two staircases arching away into the dark upper floors. How on earth did one man rattle around in such a house, even if he did have an army of servants?

Anna became aware that Mr. Hopple was speaking to her.

“The last secretary and, of course, the one before him worked in their own study under the stairs,” the little man said. “But the room there is rather bleak. Not at all fitting a lady. So I thought it best that you be set up in the library where the earl works. Unless,” Mr. Hopple inquired breathlessly, “you would prefer to have a room of your own?”

The steward turned to the library and held the door for Anna. She walked inside and then stopped suddenly, forcing Mr. Hopple to step around her.

“No, no. This will do very nicely.” She was amazed at how calm her voice sounded. So many books! They lined three sides of the room, marching around the fireplace and extending to the vaulted ceiling. There must be over a thousand books in this room. A rather rickety ladder on wheels stood in the corner, apparently for the sole purpose of putting the volumes within reach. Imagine owning all these books and being able to read them whenever one fancied.

Mr. Hopple led her to a corner of the cavernous room where a massive, mahogany desk stood. Opposite it, several feet away, was a smaller, rosewood desk.

“Here we are, Mrs. Wren,” he said enthusiastically. “I’ve set out everything I think you might need: paper, quills, ink, wipers, blotting paper, and sand. This is the manuscript the earl would like copied.” He indicated a four-inch stack of untidy paper. “There is a bellpull in the far corner, and I’m sure Cook would be happy to send up tea and any light refreshments you might like. Is there anything else you desire?”

“Oh, no. This is all fine.” Anna clasped her hands before her and tried not to look overwhelmed.

“No? Well, do let me know if you need more paper, or anything else for that matter.” Mr. Hopple smiled and shut the door behind him.

She sat at the elegant little desk and reverently ran a finger over the polished inlay. Such a pretty piece of furniture. She sighed and picked up the first page of the earl’s manuscript. A bold hand, heavily slanted to the right, covered the page. Here and there, sentences were scratched out and alternative ones scrawled along the margins with many arrows pointing to where they should go.

Anna began copying. Her own handwriting flowed small and neat. She paused now and again as she tried to decipher a word. The earl’s handwriting was truly atrocious. After a while, though, she began to get used to his looping Ys and dashed Rs.

At a little past noon, Anna laid aside her quill and rubbed at the ink on her fingertips. Then she rose and tentatively yanked at the bellpull in the corner. It was silent, but presumably a bell rang somewhere to summon someone to bring her a cup of tea. She glanced at the row of books near the pull. They were heavy, embossed tomes with Latin names. Curious, she drew one out. As she did so, a slim volume fell to the floor with a thud. Anna quickly bent to pick it up, glancing guiltily at the door. No one had yet responded to the bellpull.

She turned back to the book in her hands. It was bound in red morocco leather, buttery soft to the touch, and was without title. The sole embellishment was an embossed gold feather on the lower right corner of the cover. She frowned and replaced her first choice, then carefully opened the red leather book. Inside, on the flyleaf, was written in a childish hand, Elizabeth Jane de Raaf, her book.

“Yes, ma’am?”

Anna almost dropped the red book at the young maid’s voice. She hastily replaced it on the shelf and smiled at the maid. “I wonder if I might have some tea?”

“Yes, ma’am.” The maid bobbed and left without further comment.

Anna glanced again at Elizabeth’s book but decided circumspection was the better part of valor and returned to her desk to await the tea.

At five o’clock, Mr. Hopple rushed back into the library. “How was your first day? Not too strenuous, I hope?” He picked up the stack of completed papers and glanced through the first several. “These look very well. The earl will be pleased to get them off to the printers.” He sounded relieved.

Anna wondered if he had spent the day worrying about her abilities. She gathered her things and, with a last inspection of her desktop to make sure all was in order, bid Mr. Hopple good evening and set off home.

Mother Wren pounced the moment Anna arrived at the little cottage and bombarded her with anxious questions. Even Fanny looked at her as if working for the earl were terribly dashing.

“But I didn’t even meet him,” Anna protested to no avail.

The next several days passed swiftly, and the pile of transcribed pages grew steadily. Sunday was a welcome day of rest.

When Anna returned on Monday, the Abbey held an air of excitement. The earl had at last returned from London. Cook didn’t even look up from the soup she stirred when Anna entered the kitchen, and Mr. Hopple wasn’t there to greet her as had been his daily habit. Anna made her way to the library by herself, expecting to finally meet her employer.

Only to find the room empty.

Oh, well. Anna puffed out a breath in disappointment and set her luncheon basket down on the rosewood desk. She began her work, and time passed, marked only by the sound of her quill scratching across the page. After a while, she felt another presence and looked up. Anna gasped.

An enormous dog stood beside her desk only an arm’s length away. The animal had entered without any sound.

Anna held herself very still while she tried to think. She wasn’t afraid of dogs. As a child, she’d owned a sweet little terrier. But this canine was the largest she’d ever encountered. And unfortunately it was also fa

miliar. She’d seen the same animal not a week ago, running beside the ugly man who had fallen off his horse on the high road. And if the animal was here now . . . oh, dear. Anna rose, but the dog took a step toward her and she thought better of escaping the library. Instead, she exhaled and slowly sat back down. She and the dog eyed each other. She extended a hand, palm downward, for the dog to sniff. The dog followed her hand’s movement with its gaze, but disdained the gesture.

“Well,” Anna said softly, “if you will not move, sir, I can at least get on with my work.”

She picked up her quill again, trying to ignore the huge animal beside her. After a bit, the dog sat down but still watched her. When the clock over the mantelpiece struck the noon hour, she put down her quill again and rubbed her hand. Cautiously, she stretched her arms overhead, making sure to move slowly.

“Perhaps you’d like some luncheon?” she muttered to the beast. Anna opened the small cloth-covered basket she brought every morning. She thought about ringing for some tea to go with her meal but wasn’t certain the dog would let her move from the desk.

“And if someone doesn’t come to check on me,” she grumbled to the beast, “I shall be glued to this desk all afternoon because of you.”

The basket held bread and butter, an apple, and a wedge of cheese, wrapped in a cloth. She offered a crust of the bread to the dog, but he didn’t even sniff it.

“You are picky, aren’t you?” She munched on the bread herself. “I suppose you’re used to dining on pheasant and champagne.”

The dog kept his own counsel.

Anna finished the bread and started on the apple under the beast’s watchful eyes. Surely if it was dangerous, it would not be allowed to roam freely in the Abbey? She saved the cheese for last. She inhaled as she unwrapped it and savored the pungent aroma. Cheese was rather a luxury at the moment. She licked her lips.

The dog took that moment to stretch out his neck and sniff.

Anna paused with the lump of cheese halfway to her mouth. She looked first at it and then back to the dog. His eyes were liquid brown. He placed a heavy paw on her lap.

She sighed. “Some cheese, milord?” She broke off a piece and held it out.

The cheese disappeared in one gulp, leaving a trail of canine saliva in its former place on her palm. The dog’s thick tail brushed the carpet. He looked at her expectantly.

Anna raised her eyebrows sternly. “You, sir, are a sham.”

She fed the monster the rest of her cheese. Only then did he deign to let her fondle his ears. She was stroking his broad head and telling him what a handsome, proud fellow he was when she heard the sound of booted footsteps in the hallway. She looked up and saw the Earl of Swartingham standing in the doorway, his hot obsidian eyes upon her.

Chapter Three

A powerful prince, a man who feared neither God nor mortal, ruled the lands to the east of the duke. This prince was a cruel man and a covetous one as well. He envied the duke the bounty of his lands and the happiness of his people. One day, the prince gathered a force of men and swept down upon the little dukedom, pillaging the land and its people until his army stood outside the walls of the duke’s castle.

The old duke climbed to the top of his battlements and beheld a sea of warriors that stretched from the stones of his castle all the way to the horizon. How could he defeat such a powerful army? He wept for his people and for his daughters, who surely would be ravished and slain. But as

he stood thus in his despair, he heard a croaking voice. “Weep not, duke. All is not yet lost. . . .”

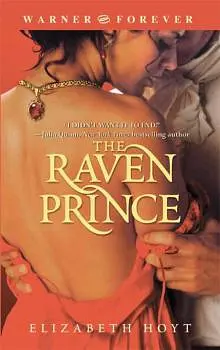

—from The Raven Prince

Edward halted in the act of entering his library. He blinked. A woman sat at his secretary’s desk.

He repressed the instinctive urge to back out a step and double-check the door. Instead he narrowed his eyes, inspecting the intruder. She was a small morsel dressed in brown, her hair hidden by a god-awful frilled cap. She held her back so straight, it didn’t touch the chair. She looked like every other lady of good quality but depressed means, except that she was petting—petting for God’s sake—his great brute of a dog. The animal’s head lolled, tongue hanging out the side of his jaw like a besotted idiot, eyes half shut in ecstasy.

Edward scowled at him. “Who’re you?” he asked her, more gruffly than he’d meant to.

The woman’s mouth thinned primly, drawing his eyes to it. She had the most erotic mouth he’d ever seen on a woman. It was wide, the upper lip fuller than the lower, and one corner tilted. “I am Anna Wren, my lord. What is your dog’s name?”

“I don’t know.” He stalked into the room, taking care not to move suddenly.

“But”—the woman knit her brow—“isn’t it your dog?”

He glanced at the dog and was momentarily mesmerized. Her elegant fingers were stroking through the dog’s fur.

“He follows me and sleeps by my bed.” Edward shrugged. “But he has no name that I know of.”

He stopped in front of the rosewood desk. She’d have to move past him in order to escape the room.

Anna Wren’s brows lowered disapprovingly. “But he must have a name. How do you call him?”

“I don’t, mostly.”

The woman was plain. She had a long, thin nose, brown eyes, and brown hair—what he could see of it. Nothing about her was out of the ordinary. Except that mouth.

The tip of her tongue moistened that corner.

Edward felt his cock jump and harden; he hoped to hell she wouldn’t notice and be shocked out of her maidenly mind. He was aroused by a frumpy woman he didn’t even know.

The dog must’ve grown tired of the conversation. He slipped from beneath Anna Wren’s hand and lay down with a sigh by the fireplace.

“You name him if you must.” Edward shrugged again and rested the fingertips of his right hand on the desk.

The assessing stare she leveled at him stirred a memory. His eyes narrowed. “You’re the woman who made my horse shy on the high road the other day.”

“Yes.” She gave him a look of suspicious sweetness. “I am so sorry you fell off your horse.”

Impertinent. “I did not fall off. I was unseated.”

“Indeed?”

He almost contested that one word, but she held out a sheaf of papers to him. “Would you care to see what I’ve transcribed today?”

“Hmm,” he rumbled noncommittally.

He withdrew his spectacles from a pocket and settled them on his nose. It took a moment to concentrate on the page in his hand, but when he did, Edward recognized the handwriting of his new secretary. He’d read over the transcribed pages the night before, and while he’d approved of the neatness of the script, he’d wondered about the effeminacy of it.

He looked at little Anna Wren over his spectacles and snorted. Not effeminate. Feminine. Which explained Hopple’s evasiveness.

He read a few sentences more before another thought struck him. Edward darted a sharp glance at the woman’s hand and saw she wore no rings. Ha. All the men hereabouts were probably afraid to court her.

“You are unwed?”

She appeared startled. “I am a widow, my lord.”

“Ah.” Then she had been courted and wed, but not anymore. No male guarded her now.

Hard on the heels of that thought was a feeling of ridiculousness for having predatory thoughts about such a drab female. Except for that mouth . . . He shifted uncomfortably and brought his wandering thoughts back to the page he held. There were no blots or misspellings that he could see. Exactly what he would expect from a small, brown widow. He grimaced mentally.

Ha. A mistake. He glared at the widow over his spectacles. “This word should be compost, not compose. Can’t you read my handwriting?”

Mrs. Wren took a deep breath as if fortifying her patience, which made her lavish bosom expand. “Actually, my lord, no, I can’t always.”

“Humph,” he grunted, a little disappointed she hadn’t argued. She’d probably have to take a lot of deep breaths if she were

enraged.

He finished reading through the papers and threw them down on her desk, where they slid sideways. She frowned at the lopsided heap of papers and bent to retrieve one that had fluttered to the floor.

“They look well enough.” He walked behind her. “I will be working here later this afternoon whilst you finish transcribing the manuscript thus far.”

He reached around her to flick a piece of lint off the desk. For a moment, he could feel her body heat and smell the faint scent of roses wafting up from her warmth. He sensed her stiffen.

He straightened. “Tomorrow I’ll need you to work with me on matters pertaining to the estate. I hope that is amenable to you?”

“Yes, of course, my lord.”

He felt her twist around to see him, but he was already walking toward the door. “Fine. I have business to attend to before I begin my work here.”

He paused by the door. “Oh, and Mrs. Wren?”

She raised her eyebrows. “Yes, my lord?”

“Do not leave the Abbey before I return.” Edward strode into the hallway determined to hunt down and interrogate his steward.

IN THE LIBRARY, Anna narrowed her eyes at the earl’s retreating back. What an overbearing man. He even looked arrogant from the rear, his broad shoulders straight, his head at an imperious tilt.

She considered his last words and turned a puzzled frown on the dog sprawled before the fire. “Why does he think I’d leave?”

The mastiff opened one eye but seemed to know that the question was rhetorical and closed it again. She sighed and shook her head, then drew a fresh sheet of paper from the pile. She was his secretary, after all; she’d just have to learn to put up with the high-handed earl. And, of course, keep her thoughts to herself at all times.

Three hours later, Anna had nearly finished transcribing the pages and had a crick in her shoulder for her efforts. The earl hadn’t yet returned, despite his threat. She sighed and flexed her right hand, then stood. Perhaps a stroll about the room was in order. The dog looked up and rose to follow her. Idly, she trailed her fingers along a shelf of books. They were outsized tomes, geography volumes, judging by the titles on their spines. The books were certainly bigger than the red-bound one she’d looked at last week. Anna paused. She hadn’t had the courage to inspect that little volume since she’d been interrupted by the maid, but now curiosity drove her to the shelf by the bellpull.