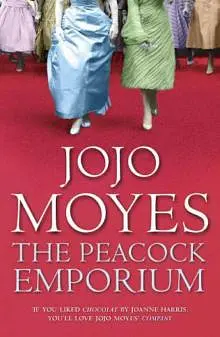

by Jojo Moyes

Rosemary Fairley-Hulme, who had become accustomed to her son's restored presence in the family house, had panicked when he didn't arrive home by late evening, and even more so when she realised that neither she nor her husband had any idea where he had spent the day. Until midnight she had paced the creaking floorboards, glancing out of the leaded windows in the vain hope of seeing twin headlights coming slowly up the drive. The housekeeper, roused from her bed, told Rosemary that she had seen Mr Douglas take a taxi to the station at ten o'clock that morning. The Stationmaster, when she got Cyril to ring him, said he had been wearing his good suit. 'Up for a show, was he?' he asked jovially. 'Good for him to let his hair down a little.'

'Something like that, Tom,' said Cyril Fairley-Hulme, and put down the receiver.

That was the point at which they had rung Vivi, hoping against hope that although when she came to Dere House several times a week, he appeared to pay her no more heed than the furniture perhaps just this once, their son had taken her into town.

'Gone?' said Vivi, and felt a lurch of fear when she understood that Douglas, her Douglas, who had spent the past months weeping privately on her shoulder, confiding his darkest feelings about the departure of his wife, had been keeping something from her.

'We were rather hoping he was with you. He hasn't been home all night. Cyril's out in the car looking for him now,' Rosemary had said.

'I'll be right over,' said Vivi and, despite her discomfort, felt vaguely satisfied that, despite the late hour, Rosemary had seemed to think this appropriate.

Vivi had rushed over to the estate, unsure whether she was more afraid that he was lying injured in a ditch or that his disappearance was linked to the reappearance of someone else. He still loved Athene, she knew it. She had had to hear him say it often enough over the past months. But that had been bearable when she could believe that his feelings had been dying, like the embers of a fire - one that, now she had heard all the details, she had not thought would be restoked.

Between the hours of midnight and dawn, split into small groups, armed with flashlights, they had combed the estate, in case he had walked home drunk and fallen into a ditch. A lad had done this several years previously and drowned; the memory of finding that body face down in several inches of stagnant water haunted Cyril still.

'He's not drunk much since the first weeks,' he said, as they strode along, bumping gently against each other in the moonlight. 'The boy's past the worst. Much more himself.'

'He'll be at a friend's, Mr Fairley-Hulme. I'll wager he's had a few and stayed in London for the night.' The gamekeeper, who walked the Rowney Wood with the agility and confidence of someone well used to negotiating branches and tree roots in the dark, took a sanguine view of the affair. He had remarked four times now that boys would be boys.

'Might have headed over to Larkside,' muttered one of the lads. 'Most end up at Larkside one time or another.'

Vivi winced: the house on the village outskirts was spoken of in whispered tones or drunken jest and the thought of Douglas lowering himself to that level, that he might turn to women like that when she was just waiting for him to say the word . . .

'He's got more sense than to end up there.'

'Not if he's had a skinful. He's been on his own a good year.'

She heard the soft thud of the gamekeeper's boot meeting cloth, and a muttered curse.

'This is hopeless,' said Cyril. 'Bloody, bloody Douglas. Bloody inconsiderate boy.'

Vivi glanced up at his set jaw as she trudged along, her cardigan wrapped round her in a vain attempt to stave off the cold. She knew his condemnation of Douglas was designed to disguise his anxiety. He, like Vivi, knew the depths of Douglas's despair.

'He'll turn up,' she said quietly. 'He's so sensible. Really.'

No one thought to go to Philmore House. Why would they, when he had hardly set foot there since she had left? So it was only an hour after dawn broke, when the two search parties converged in the cold light, chilled and increasingly silent, outside the Philmore barns, that anyone thought of it.

'There's a light, Mr Fairley-Hulme,' said one of the lads, gesturing. 'In the upstairs window. Look.'

And as they stood on the overgrown, dew-soaked lawn, their eyes raised to the upper floors of the old house, the sound of birdsong building to a swell around them, the front door had opened. And there he had stood, his shadowed eyes betraying his own night of lost sleep, his good suit trousers wrinkled and his shirt-sleeves rolled up, a child sleeping peacefully in his arms.

'Douglas!' Rosemary's exclamation had held a mixture of shock and relief.

There had been a brief silence then, as the little group of people properly took in the sight in front of them.

Douglas looked down, and adjusted the shawl around the baby.

'What's going on, son?'

'This . . . is Suzanna,' he said quietly. 'Athene has given her to me. That is all I want to say on the matter.' He looked both bruised and defiant.

Vivi's mouth had dropped open, and she closed it. She heard the gamekeeper curse vigorously under his breath.

'But we thought - oh, Douglas, what on earth has been--'

Cyril, his eyes fixed on his son, stayed his wife with a hand on her shoulder. 'Not now, Rosemary.'

'But, Cyril! Look at the--'

'Not now, Rosemary.' He nodded at his son, and turned back towards the drive. 'Let's all get some rest. The boy's safe.'

Vivi felt him propel her gently across the lawns: she, too, was expected to leave.

'Thank you, everyone,' she heard him say, as she glanced back towards Douglas, who was still gazing at the gently illuminated face of the child. 'If you'd like to head back to Dere House I think we could all do with some coffee. Plenty of time for talking when we've had some sleep.'

He had gone to Philmore House, Douglas told Vivi long afterwards, because he had needed to be alone, was unsure whether he could admit even to himself the truth of what had happened that day. Perhaps he went because, carrying Athene's child, he felt some primeval urge to be closer to her mother, to take the child to where some familiarity, some sense of her, might rub off. Either way, he stayed at the house only two days before he found that coping alone with a baby was beyond him.

Rosemary had, at first, been incandescent with fury. She would not have that woman's child in the house, she exclaimed, when Douglas arrived at the family home. She could not believe he'd been so stupid, so gullible. She could not believe he would expose himself to such ridicule. What next? Would they be expected to put up Athene's lovers too?

That had been the point at which Cyril had told her to go off for a bit, get some air. In a quieter, more measured voice, he had tried to reason with his son. He had to see sense, didn't he? He was a young man, he couldn't be saddled with bringing up a baby. Not with his whole life ahead of him. Especially one who . . . The words were left unspoken. Something in Douglas's implacable stare had halted him mid-sentence.

'She's staying here,' Douglas had said. 'That's all there is to it.' He already held her with the relaxed dexterity of the young father.

'And how will you support her?' Cyril said. 'You can't expect us to carry you. Not with all the work that needs doing on the estate. And your mother won't do it. You know she won't.'

'I'll sort something out,' said Douglas.

Later he confided to Vivi that his quiet determination had not just been about his desire to keep the child, although he had loved her already. He didn't like to admit to his father that even if he had wanted to give Suzanna back, had chosen to accede to his family's wishes, he hadn't thought to ask Athene how he should get in touch with her.

The first few days had been farcical. Rosemary had ignored the child's presence, and busied herself in her garden. The estate wives had been less condemnatory, or at least to his face, bringing, as they heard the news, their old high chairs, bibs and muslins, a whole arsenal of baby necessities that he had not considered might be necessary for the care of one small

human being. He had begged Bessie to advise him on the basics, and she had spent a morning explaining the correct pinning of a napkin, how best to heat bottles of milk, how to make solid food digestible by mashing it with a fork. She had watched from afar, disapproval mingling with anxiety for the child as he tried hamfistedly to feed her, swearing and wiping food off his clothes as the little one batted the loaded spoon away from her face.

Within days he was exhausted. His father's patience had been stretched by Douglas's inability to work, the papers piled up in the study and the men were complaining about lack of direction on the land.

'What are you going to do?' said Vivi, having watched as he jiggled the baby under his arm while trying to negotiate with a feed merchant on the telephone. 'Why don't you get a wet-nurse, or whatever it is that babies have?'

'She's too old for a wet-nurse,' he replied, lack of sleep making him snappy. He didn't say what they both thought: that the child needed her mother.

'Are you all right? You look awfully tired.'

'I'm fine,' he said.

'But you can't possibly manage everything by yourself.'

'Don't you start, Vee. Not you with everyone else.'

She bridled, hurt at his assumption that she belonged with 'everyone else'. She watched silently as he walked up and down the room, dangling his keys in front of the baby's grasping hands, muttering some checklist under his breath.

'I'll help you,' she said.

'What?'

'I've got no work at the moment. I'll look after her for you.' She didn't know what had made her say it.

His eyes widened, hope flickering across his face. 'You?'

'I've done toddlers. Babysat them, I mean. When I was in London. One of her age can't be that much harder.'

'You'd really look after her?'

'For you, yes.' She blushed at her choice of words, but he didn't seem to notice.

'Oh, Vee. You'd really look after her? Every day? Until I can get something else sorted out, of course. Till I can work out what to do.' He had walked towards her, as if he was already keen to hand Suzanna over.

She hesitated then, suddenly seeing in that dark, satiny hair, the wide blue eyes, the memory of a painful time before. Then she looked back at him, at the relief and gratitude on his face.

'Yes,' she said. 'Yes, I would.'

Her parents had been appalled. 'You can't do this,' her mother had said. 'It's not even your child.'

'We mustn't visit the sins of the fathers, Mummy,' she had replied, sounding more confident than she felt. 'She's a perfectly adorable baby.' She had just rung Mr Holstein to tell him she wouldn't be returning to London.

Mrs Newton, agitated, had gone so far as to call on Rosemary Fairley-Hulme, and had been surprised to find her just as fierce in her opposition to the whole sorry scheme. The young people appeared to have made up their minds, said Rosemary, despairingly. There was certainly no telling Douglas.

'But, darling, think about it. I mean, she could come back at any time. And you have your job, your career. This could go on for years.' Her mother had been close to tears. 'Think, Vivi. Think of how he hurt you before.'

I don't care. Douglas needs me, she said silently, enjoying the sensation of being united with him against the world. That's good enough for me.

They had all softened in the end. They had to: who could hold out against a beaming, beautiful, innocent baby? Vivi found that - as the months went on, as Suzanna's presence in the house became less remarkable, as the explanations for her appearance were less discussed in the village - occasionally, on hearing the child cry, Rosemary would emerge from her kitchen 'just to check she was all right', that Cyril, finding her in his son's arms before her bath, would chuck her cheek and blow raspberries at her. Vivi, meanwhile, was besotted, her exhaustion blown away by the uninhibited smiles, the clutching hands and blind trust. Suzanna brought her and Douglas together too: every evening, over a gin and tonic, when he came in from the fields, they would sit and laugh over her little foibles, commiserate over her teeth or sudden, mercurial tempers. When she had taken her first steps, Vivi had run all the way to the forty-acre field to find him, and they had run back together, breathless and expectant, to where she sat with the housekeeper, gazing around her with the benignly merry countenance of the much-adored. And there had been one perfect day when they had taken her out together, wheeling the big old pram across the estate to have a picnic, as if, Vivi thought secretly, furtively, they were a real family.

Douglas had been cheerful that day, had held the child close, pointing out the barns, a tractor, birds slicing through the sky. And something about the perfection of it all, about her own happiness, had forced the question to Vivi's lips. 'Will she want her back?' she had asked.

He had lowered his pointed finger. 'I'm going to tell you something, Vee. Something I haven't told anyone.' His eyes, which had been bright and cheerful, looked suddenly haunted.

With the baby seated between them, he had told her exactly how this child had ended up in his care, how he had foolishly gone to that restaurant believing that Athene had wanted to see him for another reason, how even in the face of his own ignorance, his stupidity, he had been unable to deny her anything.

Vivi knew now that the reason he loved this child so much was because she was an abiding link with his former wife: he believed that while he held her, cared for her, there was a strong possibility that Athene might return. And that no matter how much he confided in Vivi, how much he depended on her, how much time they spent talking babies or acting out life as a real family, she would never be able to traverse that barrier.

I mustn't begrudge her, she thought, pretending there was something in her eye and ducking away. I mustn't begrudge a child its mother, for goodness sake. It must be enough that he needs me at all, that I am still part of his life.

But she couldn't help it. It wasn't just about Douglas any more, she thought, as she tucked baby Suzanna into her cot that evening, blessing her face with kisses, as with a contented suck of her fingers, she settled down to sleep. She didn't want to give either of them back.

Six months to the day after Suzanna had arrived, Rosemary had telephoned shortly before breakfast. She knew Vivi had been planning to go to town, but could she possibly take Suzanna for the day? she said, her voice brusque.

'Of course, Rosemary,' said Vivi, mentally rewriting her plans. 'Is there a problem?'

'There's been . . . it's . . .'

Afterwards Vivi realised that, even then, Rosemary had been reluctant to say her name.

'We've had a call. It's all a bit difficult.' She paused. 'Athene has . . . has passed away.' There was a stunned silence. Vivi's breath stuck in her throat. She was sorry, she said, shaking her head, but wasn't sure what Rosemary had just told her.

'She's dead, Vivi. We've had a call from the Forsters.' It was as if each time she said it, Rosemary gained a little more confidence, until eventually she could be matter-of-fact about it.

Vivi sat down heavily on the hall chair, heedless of her mother who, in her dressing-gown, was trying to gauge what was going on. 'Are you all right, darling?' she kept mouthing, stooping in an attempt to meet her daughter's eye.

Athene would not be coming back. She would not be returning to take Douglas and Suzanna away from her. Stunned as she was, Vivi saw that her shock was tinged with something uncomfortably close to elation.

'Vivi? Are you still there?'

'Is Douglas all right?'

She had always felt guilty afterwards that he had been her primary concern, that she had not even thought to ask into the circumstances of Athene's death. 'He will be,' said Rosemary. 'Thank you for asking, Vivi. He will be. We'll drop the baby off in half an hour.'

Douglas had mourned for two months, revealing a level of grief that many around him felt excessive, considering his wife had bolted more than a year previously and everyone knew she had taken up with another man.

Vivi didn't. Vivi thought his grief touching, a sign

of how deeply, how passionately he could feel. She could afford to be generous about it now that Athene was gone. She didn't dwell on Athene's death, finding it impossible to settle on the right balance of sympathy and opprobrium, so instead focused on Suzanna, as if she could atone for her mean-spirited thoughts by flooding the child with love. She had taken sole charge of the child for weeks now, finding that without the threat of Athene's return, an almost shocking amount of it poured from herself into the now motherless child.

Suzanna seemed to respond to Vivi's uninhibited affection and became sunnier even than she had been before, placing her soft, cushioned cheek against hers, wrapping fat starfish fingers around her own. Vivi would arrive shortly after seven thirty, and take the child for long walks around the estate, removing her from Douglas's grief, which hung over the house like a dark cloud, and from the whispered conversations of his parents and the servants, all of whom seemed to consider Suzanna's presence a problem now of some pressing urgency.

'We can't get rid of her now,' she had heard Rosemary saying to Cyril, as she passed the study. 'We've told everyone the child is Douglas's.'

'The child is Douglas's,' Cyril had said. 'He'll have to decide what he wants to do with her. Tell the boy to pull himself together. He's got decisions to make.'

They were clearing Philmore House. The home that had remained a shrine to Athene - whose wardrobes still bulged with her dresses, whose ashtrays still bore her lipsticked cigarette butts - had fallen into Rosemary's list of responsibilities. Douglas and Suzanna were now firmly ensconced in Dere House. And Rosemary, who had long itched to remove the physical evidence of 'that girl' from the estate, had taken advantage of her son's newly passive state to deal with it.

Vivi stood on the brow of the hill, holding her hat on her head as she watched the men come out, bearing armfuls of brightly coloured dresses and laying them on the front lawn, while the women, kneeling on rugs and braced against the chill, sorted through bags and boxes of jewellery and cosmetics, exclaiming among themselves at their quality.

For someone who had professed herself so unconcerned with belongings, Athene had had a prodigious amount of things - not just dresses, coats and shoes but records, pictures, lamps, beautiful things bought in haste and discarded, or received as gifts that had been soon forgotten.