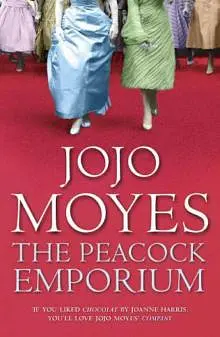

by Jojo Moyes

'I don't understand.' He stepped up towards her so that his head was level with hers.

'Like hell you don't. You should talk to her, Ale. If one of you doesn't do something soon, I'm going to faint under the weight of all the unspoken longing in the air.'

He looked at her steadily for some time. 'She is married, Jess. And I thought you were the great believer - in fate, I mean. One man for one woman, right?'

'I am,' she said. 'Not anyone's fault if the first time round you get the wrong one.'

The tape machine, which had been playing a jazz compilation, switched itself off abruptly, leaving a silence within the shop, allowing acoustic space for the dull rumble of an approaching storm outside.

'I think you are a romantic,' he said.

'Nope. I think sometimes people need a bit of a shove.' She shifted on her step. 'Including me. Come on, let's get out of here. My Emma will be wondering where I am. She's coming to watch me get my nails done this evening. First time ever. I can't decide whether to go for some tasteful pink or a lovely tarty scarlet.'

He held out his arm, and she took it, using it as a lever with which to raise herself from her seated position. 'God,' she said, as they emerged into the glowing shop. 'I'm absolutely filthy.'

He shrugged his agreement, patted himself down, glanced out at the rain. 'You have an umbrella?'

'Raincoat,' she said, gesturing towards her fuchsia-coloured plastic mackintosh. 'Essential English summer garment. You'll learn.' She moved towards the door.

'You think we should ring Suzanna ? ' Alejandro said, casually. 'See if she's okay?'

'She'll be stuck in A and E for hours.' Jess checked the keys in her hand. 'But I've got to drop these round at hers later so I'll tell her you were asking after her, if you like . . .' She grinned, allowing a hint of mischief into her look.

He refused to answer her, shook his head in mock exasperation. 'I think, Jessie, you should keep your schemes to Arturro and Liliane.' He stooped to peel off a piece of parcel tape that had somehow attached itself to his trouser leg. Later, he would say he had heard only the beginning of Jessie's laugh, a laugh that was interrupted by a rushing noise, a screech that was, in its escalating volume and velocity, like the sound of a vast, angry bird. He had looked up in time to see the blur of white, the ear-splitting crack of what might have been thunder, and then the front of the shop exploding inwards, in a crash of noise and timber. He had lifted his arm to protect himself against the shower of splintering glass, the flying shelves, plates, pictures, had fallen backwards against the counter, and all he had seen, all he had seen, was not Jessie, but the flash of bright pink plastic as it disappeared, like a wet carrier-bag, under the front of the van.

It was her fourth cup of machine coffee, and Suzanna realised that if she drank any more her hands would begin to shake. It was hard, though, given the tedium of waiting in the cubicle, and disappearing for coffee seemed to be the only way of legitimately escaping Rosemary's relentlessly bad humour. 'If she says, "The NHS isn't what it used to be," one more time,' she whispered to Vivi, seated beside her, 'I'm going to take a swing at her with a bedpan.'

'What are you saying?' said Rosemary, querulously, from the bed. 'Do speak up, Suzanna.'

'I shouldn't bother, dear,' muttered Vivi. 'These days they're made of the same stuff as eggboxes.'

They had been there almost three hours. Rosemary had initially been seen by a triage nurse, sent for various X-rays and diagnosed with a fractured rib, bruising and a sprained wrist. Then she had been apparently removed from the urgent board, and placed at the end of a long queue of mundane injuries, which she had taken as a personal affront. The rain didn't help, the young nurse had said, then informed them that it was likely to be another hour at least. Always more accidents in the rain.

Suzanna glanced every few minutes at her left hand, as if it bore the visible sign of her duplicity. Her heart leapt every time she thought of the man who possibly still stood in her shop. This is wrong, she would tell herself. You're doing it again. Overstepping the line. And then felt the quicksilver racing of her pulse as she allowed herself, yet again, to replay the events of the previous hours.

Vivi leant towards her. 'You go, dear. I'll get a taxi home.'

'I'm not leaving, Mum. Honestly, I can't leave you alone like this.' With her, went the unspoken addition.

Vivi squeezed her arm gratefully. 'I should tell you how Rosemary did it,' she whispered.

Suzanna turned to her, and Vivi glanced behind her, about to impart some piece of information when, with a swishing sound, the cubicle curtain was pulled back.

A policeman was standing in front of them, his walkie-talkie hissing and stopping abruptly. A female officer was behind him, talking into her own.

'I think you want the end cubicle,' said Vivi, leaning forward conspiratorially. 'They're the ones who've been fighting.'

'Suzanna Peacock?' said the policeman, looking from one to the other.

'Are you going to arrest me?' said Rosemary loudly. 'Is it an offence to wait for several hours in a hospital now?'

'That's me,' said Suzanna, thinking, This is like a film. 'Is it - is it Neil?'

'There's been an accident, madam. We think you'd better come with us.'

Vivi lifted her hand to her mouth. 'Is it Neil? Has he had a crash?'

Suzanna was rooted to the spot, cold with guilt. 'What?' she said. 'What is it?'

The policeman looked reluctantly at the older women.

'They're my family,' said Suzanna. 'Just tell me, what is it?'

'It's not your husband, madam. It's your shop. There's been a serious incident and we'd like you to come with us.'

Nineteen

Suzanna had spent almost an hour and forty minutes, on and off, in the room with the detective sergeant. She learnt that he took his coffee black, that he was almost always hungry, although for the wrong sort of food, that he thought women should always be addressed as 'madam', with a kind of exaggerated deference that suggested he didn't genuinely believe it. He wouldn't tell her, initially, what had happened as if, despite her repeated insistence that it was her shop, that her friends had been inside it, all information had to be on a need-to-know basis. She was only allowed odd snippets, offered grudgingly after the detective was called out by whispering underlings, then returned to his desk. She learnt all this stuff because the only one of her senses that seemed to be working efficiently was her ability to register unimportant detail. In fact, she thought she could probably recall any single facet of this room, of the orange plastic chairs, of the stackable public-facility tables, of the cheap foil ashtrays provided in stacks by the door.

What she couldn't do was take in anything that they said.

They had wanted to know about Jessie. How long had she worked at the shop? Did she have any - here they hesitated, looked at her meaningfully - problems at home ? They wouldn't tell her what had happened, but from the unsubtle direction of the questions she had realised it must be to do with Jason. Suzanna, her mind racing headlong into a thousand possibilities, had been reluctant to say too much before she could speak to Jessie, conscious that her friend's hatred of Jason's actions was only matched by her horror of people knowing about them.

'Is she badly hurt?' she would say periodically. 'You've got to tell me if she's all right.'

'All in good time, Mrs Peacock,' he said, scribbling in an illegible hand on the pad in front of him. He had an unopened Mars bar in his top pocket. 'Now, did Miss Carter have any . . .' hesitation, meaningful look '. . . male friends that you knew about?'

She had told them in the end, rationalising that it was surely the better path for Jessie. She made the detective promise that if she told him what she knew he would have to tell her the truth about what had happened to her friend. She owed Jason no loyalty, after all. She had told them, in something of a rush, about Jessie's injuries, about her devotion to and reservations about her partner, about her determination to go through with counselling. She told

them, fearful of making Jessie sound like a victim, how determined she was, and unafraid, and how loved she was by almost everyone in the small town. She had become breathless as she finished, as if the words had forced themselves out without sufficient thought, and she had sat in silence for several minutes trying to work out whether there was anything incriminating in what she had just told them.

The detective had noted her words carefully, eyed the woman police officer next to him, and then, just as she was about to ask for directions to the ladies' room, told her, in tones that had long learnt to disguise shock and horror under an exterior of calm concern, that Jessie Carter had been killed instantly that evening when someone drove a van into the front of the shop.

Suzanna's stomach had dropped away. She had looked blindly at the two faces in front of her, two faces, she realised, in a distant, still functioning part of her mind, that were studying her own reaction. 'I'm sorry?' she said, when she could make her mouth form words. 'Could you repeat what you just said?'

The second time he said it, she experienced a sudden sensation of falling, the same feeling she had had when she was rolling down the hill with Alejandro, the spinning discombobulation of a world off its axis. Except there was no joy this time, no exhilaration, just the sickening echo of the policeman's words as they came back to her.

'I think you must have made a mistake,' she said. Then the detective had stood, offered her his arm, and said they needed her to come to the shop and determine whether anything was obviously missing. They would call anyone she needed. If she liked, they could wait while she had a cup of tea. They understood it would be something of a shock. He smelt, she noted, of cheese and onion crisps.

'Oh, and by the way, do you know an Alejandro de Marenas? ' He had read the name off a piece of paper, pronounced it with a J, and she had nodded dumbly, wondering briefly whether they thought Ale had done it. Done what ? she corrected herself. They make mistakes all the time, she told herself, feeling her legs raise her as if they were not connected to her. Look at the Guildford Four, the Birmingham Six. Who said the police always knew what they were talking about? There was no way that Jessie could be dead. Not dead dead.

And then they had stepped out into the corridor, with its stale echoes of antiseptic and old cigarette smoke, and she had seen him, sitting on the plastic chair, his dark head in his hands, the policewoman next to him resting an awkwardly comforting hand on his shoulder.

'Ale?' she had said.

As he lifted his head, the hollow shock, the new landscape of raw, wrenching bleakness on his face as his eyes met hers, confirmed everything the policeman had said, and she had let out a great guttural sob, her hands lifting involuntarily to her mouth as the sound echoed down the empty corridor.

After that the night had become a blur. She remembered being taken to the shop, standing shivering behind the yellow tape with the policewoman murmuring behind her, and staring at the collapsed frontage, the splintered windows, whose top rows still held their Georgian glass as if denying the reality of what had happened below. The electrics had apparently survived the impact, and the shop was glowing incongruously, like the interior of an oversized doll's house, its shelves still intact and neatly stacked along the back wall, alongside the north African maps, all still neatly pasted, as if refusing to bow to the fact of the carnage below them.

At some point, it had stopped raining, but the pavements still gleamed with neon reflections from the floodlights positioned by the firemen. Two were standing under what had been the door frame, gesturing at the wood, and muttering in lowered voices to the policeman in charge. They stopped talking when the policewoman shepherded Suzanna through. 'Stand here,' the policewoman said in her ear. 'This is about as close as we can get for now.'

Around her, police and firemen stood in huddles, murmuring into walkie-talkies, taking pictures with flashing cameras, cautioning the few onlookers to move away from the scene, telling them there was nothing to look at here, nothing at all. Suzanna heard the clock in the market square strike ten, and pulled her coat round her, treading carefully on the wet pavement, where her suede-covered notebooks, the hand-embroidered napkins lay sodden, surrounded by shards of glass, price labels smudged with rain. Above her, the sign swung half off, the end of the word 'Emporium' apparently carried away with the impact. She moved forward unconsciously, as if to restore it to its place, then halted as she saw several faces glance warily towards her, their expressions telling her she no longer had the right. It was no longer her shop.

It was evidence.

'We've moved as much stock away from the front as we can,' the policewoman was saying, 'but obviously until the scaffolders get here we can't vouch for the safety of the building. I'm afraid I can't let you go in.'

She was standing, she realised absently, on part of Sarah Silver's display. The MFI catalogue that Jessie had thought so funny. She bent down and picked it up, wiping her own wet footprint from it with her hand.

'If the rain still holds off, though, you shouldn't lose too much. I take it you're insured.'

'She shouldn't have been here tonight,' Suzanna said. 'She only offered to stay because I had to take my grandmother to hospital.'

The policewoman looked at her sympathetically, laid a hand on her upper arm. 'You mustn't blame yourself,' she said, her tone oddly confidential. 'This wasn't your fault. Good people always think they must be responsible in some way.'

Good? thought Suzanna. Then she caught sight of the breakdown truck, which, some thirty feet away, bore the crumpled white van like a precious cargo, its windscreen punched through by some terrible force. Suzanna stepped towards it, tried to read the lettering on the side. 'Is that Jason's van? Her boyfriend's van?'

The policewoman looked awkward. 'I'm really sorry. I don't know. Even if I did I probably wouldn't be able to tell you. It's officially a crime scene.'

Suzanna stared at the catalogue in her hand, measuring the woman's words in her head, trying to imbue them with some kind of meaning. What would Jessie say about this? she thought. She pictured her face, alive with the excitement of it all, wide-eyed with the sheer pleasure of something actually happening in her home town.

'Is he alive?' she said suddenly.

'Who?'

'Jason.'

'I'm really sorry, Mrs Peacock. I can't tell you anything at the moment. If you ring the station tomorrow, I'm sure you'll be able to get some more information.'

'I don't understand what has happened.'

'I don't think anyone can be entirely sure of what happened yet. But we'll find out, don't you worry about that.'

'She's got a little girl,' Suzanna said. 'She's got a little girl.' She stood still as the breakdown truck, accompanied by several unidentified shouts and a policeman making wheeling motions with his arm, began to tow its unhappy load slowly up the unnaturally lit lane, accompanied by the shrill command of reversing warnings and the interrupted, exhalatory hiss of the police radios.

'Is there anything personal in there? Anything vital you'd like us to get out for you? Keys? Wallet?'

Suzanna felt the bite of her words, hearing for the first time the request that now could never be satisfactorily answered. Her eyes were too dry for tears. She turned slowly back to the policewoman, placed the catalogue carefully on the wall beside the shop. 'I'd like to go now, please,' she said.

The police had rung her mother some time previously to say that she would probably be at the station for a while. Vivi, having checked anxiously that Suzanna didn't want her there, that her father couldn't come and pick her up, had promised to ring Neil and let him know. Until tomorrow, they said, she was free to go. They could give her a ride home if she liked, even send someone to sit with her if she was feeling a bit shaky. It was nearly midnight.

'I'll wait,' she said. And three-quarters of an hour later, when he emerged, his head still bowed, his normally tanned face grey and aged by grief, Jessie's blood still grotesquely visible on his clothes, she took his bandaged arm gentl

y and said she would accompany him home. There was no one to whom she could face explaining it; no one else she could bear to be with. Not tonight, at least.

They walked the ten-minute journey through the sodium-lit town in silence, their footsteps echoing in the empty streets, the lights of the windows nearly uniformly extinguished, as above them its inhabitants slept, blissfully unaware of the night's events. The rain had brought forth the sweet, organic smell of grass and rejuvenated blooms, and Suzanna breathed in, her pleasure in it unconscious, noting with a jolt that Jessie would not breathe in the sweetened smell of that morning. That was how it felt, how it would feel from now on, the mundane mixed with the surreal: a strange sense of normality, perversely interrupted by great hiccups of horror. Perhaps we are incapable of taking this in, thought Suzanna, wondering at how calm she now felt. Perhaps there is only so much to be borne at any one time. She didn't know: she had nothing to judge it against, after all. No one she knew had ever died.

She wondered, briefly, at how her family might have reacted to her mother's death. It was impossible to picture. Vivi had for so long been the maternal core of the family that Suzanna could create no imaginary sense of loss in a family that existed without her. They reached the nurses' quarters, and a security guard, patrolling the perimeter with his straining, whining dog, waved a salute as Alejandro walked her along the Tarmac path to the block. Probably not such an unusual sight, Suzanna thought absently, picturing them as the security guard must, a nurse and her boyfriend returning from some boozy night out. Alejandro fumbled with the lock, apparently unable to locate his keys. She took them from him, let them both into the silent flat. She took in its emptiness, its impersonality, as if he were determined to be only a temporary visitor. Or perhaps that he felt no right to make an impact on it.

'I'll make us some coffee,' she said.

He had washed and changed, on her instructions, then sat down on the sofa, obedient as a child. Suzanna had watched him for a moment, wondering at what horrors he had seen, at events she was not yet brave enough to ask about.