by Jojo Moyes

A brief silence followed. Then Rosemary lifted her head and began to speak, as if to someone mentally impaired: 'Vivi,' she said, deliberately, 'this is not what this family does--'

'Rosemary,' Vivi interrupted, 'in case it has escaped your notice, I am this family. I am the person who makes the meals, who irons the clothes, who keeps the house clean, and who has done for the last thirty or so years. I am the bloody family.'

Douglas's mouth had opened fractionally. But she didn't care. It was as if a kind of madness had infected her. 'That's right. I am the person who washes your dirty smalls, who is the butt of everyone else's bad moods, who cleans up after everyone else's pets, the person who does their best to try to hold the whole bloody thing together. I am this family. I may have been Douglas's second choice, but that doesn't mean I'm second best--'

'No one ever said you--'

'And I deserve an opinion. I - too - deserve - an - opinion.' Her breath came in gasps, tears pricking her eyes. 'Now, Suzanna is my daughter, as much as she is anybody's, and I am sick, sick, I tell you, of having this family, my family, divided over something as trivial as a house and a few acres of bloody land. It's unimportant. Yes, Rosemary, compared to my children's happiness, to my happiness, it really is unimportant. So there, Douglas, I've said it. You make Suzanna an equal heir, or you tell her the bloody truth.' She reached behind her to untie her apron strings, wrenched it over her head and tossed it on to the arm of the sofa.

'And don't call me "old thing",' she said, to her husband. 'I really, really don't like it.' Then, under the stunned gaze of her husband and mother-in-law, Vivi Fairley-Hulme walked past the kitchen, where Rosemary's elderly cat was making a youthful stab at the lamb chops, and out into the evening sun.

Fourteen

The Day My Mum Got Angel's Nails

My mum's nails were really short. She never bit them - she said that when she used to do cleaning she dipped her hands in bleach too many times and they never grew strong after that. Even though she'd rub cream into them every night, the white bits never really got past the end of her finger. They used to break all the time, and when they did she'd swear and then say, 'Oops! Don't tell your dad I said that.' And I never did.

Sometimes, if I had been good, she would sit down with me and take my hand like they do in the shop and smooth cream into it, then rub a file on my nails. It made me giggle because it was all tickly. Then she would let me choose one of her bottles of polish and she would paint it on really carefully so that there were no smudges. When you do that, you mustn't pick anything up for ages because if you do you get digs in the colour, and she used to make me a drink and put a straw in it so that I could flap my hands around to dry them.

We always had to take it off again before school, but she used to let me keep it on overnight, or sometimes on a weekend. When I was in bed I used to hold my hands up and wave my fingers about because they looked so pretty, even in the dark.

The day before my mum died she booked an appointment to have some nails stuck on her fingers. She showed me them in a magazine - they were really long, and they had white tips that didn't show the dirt, because your real nails stay underneath. She said she'd always fancied having long nails, and now she was earning a bit of money she was going to treat herself. She wasn't bothered about clothes, she said, or shoes, or fancy haircuts. But beautiful nails was the one thing she really, really wanted. She was going to let me come with her after school. I'm quite good, you see. I can sit and read and be quiet, and I promised I wouldn't make a noise in the salon, and she said she knew, because I was her petal.

When my grandma got me from school and told me my mum had died I didn't cry because I didn't believe it. I thought they had got it wrong, because my mum had dropped me at drama club and she said after she picked me up she was going to get chips and we were going to have a late tea together. Then when the teacher got upset and cried I knew it wasn't a joke. Later on, when my grandma was holding me, I asked her what we were going to do about Mum's appointment. It might sound funny, but I felt worried that she was never going to go, and I knew it was something she really wanted.

Grandma looked at me for a long time, and I thought she was going to cry because her eyes went all watery. Then she held both my hands and said, 'Do you know what? We're going to make sure your mum gets her nails because, that way, she'll look just fine when she gets to heaven.'

I didn't look at my mum in her coffin on the day of the funeral even though Grandma said she looked lovely, just like she was sleeping. I asked her if someone had given her long nails, and she said that a nice lady from the salon had and that they were very beautiful, and that afterwards, if I looked up in the sky at night, I'd probably see them twinkling. I didn't say anything, but I thought that at least if Mum didn't know anyone she could wave her hand, like I used to in bed, and people wouldn't have to know she used to be a cleaner.

My dad can't do nail varnish. I was going to ask him, but I've been staying with my grandma and she says she'll do it for me, when things calm down a bit. She cries a lot. I've heard her when she thinks I'm in bed, although she always puts on her happy voice when she thinks I'm listening.

Sometimes I cry too. I really miss my mum.

Steven Arnold says my mum's nails won't be shiny by now. He says they'll be black.

Actually, I don't want to do this any more.

Fifteen

In Suzanna's teenage years, on days like these, Vivi would have described her as having woken up feeling 'a bit complicated'. It was nothing one could put one's finger on, the result of no tangible misfortune, but she had started her day overhung by an invisible cloud, with a sense that her universe was skewed in some way and that she was only a hair's breadth from bursting into tears. On such days one could usually guarantee that inanimate objects would rise (or lower themselves?) to the occasion: a piece of bread had got wedged in the toaster, and she had shocked herself trying to get it out with a fork; she had discovered a slow leak under a pipe in the bathroom, and bumped her head on the low doorway as she came out; Neil had failed to put the rubbish out, as he'd promised. She had bumped into Liliane in the delicatessen when she'd nipped in to buy a box of sugared almonds, as suggested by Jessie for the next 'love token', and been forced to whip them into her bag like a shop-lifter, which she had theoretically become when she left the shop having forgotten to pay for them. And when she finally arrived at the Emporium she had been ambushed by Mrs Creek, who told her with perverse relish that she had been waiting outside for almost twenty minutes, and asked if Suzanna could donate some of her 'bric-a-brac' for one of the pensioners' jumble sales.

'I don't have any bric-a-brac,' she had said pointedly.

'You can't tell me all of this stuff is for sale,' said Mrs Creek, staring at the display on the back wall.

Mrs Creek had then segued effortlessly into a story about dinner-dances in Ipswich and how, as a teenage girl, she had supplemented her parents' income by sewing dresses for her friends. 'When I started making my own clothes, it was all the New Look,' she said. 'Great swirling skirts and three-quarter sleeves. You used to use ever such a lot of fabric on those skirts. You know, when the fashion first came out, people here were scandalised. We'd spent years scrimping on fabric during the war, you see. There was nothing. Not even for coupons. Lots of us went out dancing in dresses we'd made from our own curtains.'

'Really,' said Suzanna, flicking on switches and wondering why Jessie was late.

'The first one I ever made was in emerald silk. Gorgeous colour it was, ever so rich. It looked like one of Yul Brynner's outfits in The King and I - you know the one I'm talking about?'

'Not really,' said Suzanna. 'Are you having coffee?'

'That's very kind of you, dear. I don't mind keeping you company.' She sat on the seat near the magazines and began pulling bits of paper from her bag. 'I've got photographs somewhere, of how we used to look. Me and my sister. We used to share dresses then. Waists that you could stick your hands round.' Sh

e breathed out. 'Men's hands, that is. Mine have always been on the small side. Of course, you had to nearly suffocate yourself with corsetry to get the look, but girls will always suffer to be beautiful, won't they?'

'Mm,' said Suzanna, remembering to take the sugared almonds from her bag, and place them under the counter. Jessie could take them over later. If she ever decided to turn up.

'She's got a colostomy now, poor thing.'

'What?'

'My sister. Crohn's disease. Causes her terrible trouble, it does. You can wear all the baggy clothing you like but you do have to make sure you don't bump into anyone, you know what I'm saying?'

'I think so,' said Suzanna, trying to concentrate on measuring coffee.

'And she lives in Southall. So there you go . . . It's a recipe for disaster. Still, it could be worse,' she said. 'She used to work on the buses.'

'Sorry I'm late,' said Jessie. She was dressed in cut-off jeans, with lavender-coloured sunglasses on her head, looking summery and almost unbearably pretty. She was followed closely behind by Alejandro, who stooped as he entered. 'His fault,' she explained cheerfully. 'He needed directing to the good butcher's. He's been a bit shocked by the state of the supermarket meat.'

'It is shocking, that supermarket,' said Mrs Creek. 'Do you know how much I paid the other day for a bit of pork belly?'

'I'm sorry,' said Alejandro, who had registered Suzanna's set mouth. 'It's hard for me to discover these things when I'm off my shift. The hours never match anyone else's.' His eyes held a mute appeal that made Suzanna feel both appeased and irritated.

'I'll make up the extra minutes,' said Jessie, shedding her bag under the counter. 'I've been hearing all about Argentinian steak. Tougher, apparently, but tastier.'

'It's fine,' Suzanna said. 'Doesn't matter.' She wished she hadn't seen the look that had passed between them.

'Double espresso?' said Jessie, moving behind the coffee machine. Alejandro nodded, seating himself at the small table beside the counter. 'Can I get you one?' she asked Suzanna.

'No,' said Suzanna. 'I'm fine.' She wished she hadn't worn these trousers. They picked up lint and fluff, and the cut, she saw, made them look cheap. Then again, what did she expect? They were cheap. She had bought no quality clothes since they left London.

'We don't really eat meat,' Jessie was saying. 'Not in the week, anyway. Apart from chicken it's too expensive - and I don't like thinking of them in all those battery cages. Plus Emma's not that bothered. But I do love roast beef. For Sunday lunch.'

'One day I will find you some good Argentinian beef,' Alejandro said. 'We let our animals get older. You will know the difference.'

'I thought old steers were meant to get stringy,' said Suzanna, and immediately regretted it.

'But you tenderise your meat, dear,' said Mrs Creek. 'You beat it with a wooden thing.'

'If the meat is good,' said Alejandro, 'it should not need beating.'

'You'd think the cow had been through enough.'

'Beef dripping,' said Mrs Creek. 'Now there's something you never see in the shops any more.'

'Isn't that the same thing as lard?'

'Can we talk about something else?' Suzanna was starting to feel queasy. 'Jessie, have you finished that coffee?'

'You never told us,' Jessie turned to Alejandro, leaning over the counter, 'about your life before you came here.'

'Not much to tell,' said Alejandro.

'Like why you wanted to be a midwife. I mean, no offence, but it's not a normal profession for a bloke, is it?'

'What is normal?'

'But you'd have to be pretty comfortable with your feminine side in a macho country like Argentina to do what you do. So why do you do it?'

Alejandro took his cup of coffee, and dropped two sugar cubes into the thick black liquid. 'You are wasted in a shop, Jessie. You should be a psychotherapist. In my home it's the most prestigious job you can have. Next to a plastic surgeon, of course . . . Or perhaps a butcher.'

Which was, Suzanna thought, as she began to unpack a new box of bags, a pretty neat way of not answering the question.

'I was just telling Suzanna I used to make dresses.'

'I know,' said Jessie. 'You showed me the pictures. Lovely, they were.'

'Have I shown you these ones?' Mrs Creek held out a fan of battered photographs.

'They're beautiful,' said Jessie, obligingly. 'Aren't you clever?'

'I think we were better with our hands then. Girls today seem to be . . . less resourceful. But then we had to be, with the war and all.'

'And what did you do, Suzanna, before you opened this shop?' His voice, with its strong accent, was low, comforting. She could imagine it, consoling, in childbirth. 'Who were you in your past life?'

'The same person I am now,' she said, aware as she spoke that she didn't believe what she was saying. 'I've got to nip out and pick up some more milk.'

'No one is the same person for ever,' insisted Jessie.

'I was the same person . . . but with less strong views on people minding their own business,' she said sharply, and slammed the till drawer.

'I come here for the atmosphere, you know,' Mrs Creek confided to Alejandro.

'Are you all right, Suzanna?' Jessie leant over to get a better view of her expression.

'Fine. Just busy, okay? There's a lot to do today.'

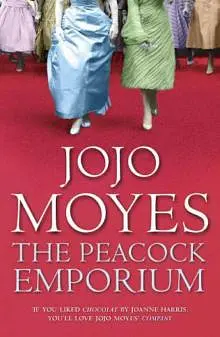

Jessie caught the implicit criticism and winced. 'That fish,' she said, to Alejandro, as Suzanna shoved mugs unnecessarily around the shelf above the till, 'the one you used to catch with your dad, the peacock something.'

'Peacock bass?'

'It's known for being really grumpy, right?'

Mrs Creek coughed quietly into her coffee.

There was a short pause.

'I think maybe it has to be grumpy, as you call it, to survive in its environment,' said Alejandro, innocently.

They waited until Suzanna, with a flashing glance their way, closed the shop door hard behind her. They watched her striding up the lane, head down, as if walking into a fierce wind.

Jessie breathed out, shook her head admiringly at the man opposite. 'Blimey, Ale, I'm not the only one who's wasted in my job.'

Father Lenny walked down Water Lane, turned left and nodded through the window at the occupants of the Peacock Emporium and, on seeing the cheerful face surrounded by blonde plaits, waved vigorously. He thought back to the conversation he had had earlier that morning.

The boy - for he was still a boy, no matter what maturity he thought paternity had conferred - had come to deliver a storage heater to the presbytery. The central heating was next to useless, these days, and the diocese funds wouldn't run to a new system. Not with the church roof needing doing. They knew of Lenny's reputation, knew he could always be relied upon to scrape by on his contacts; after twenty years they turned a blind eye to any commercial activities that might, on close inspection, appear a little inappropriate compared with those normally undertaken by servants of the Church. So the delivery van had turned into the drive, and Lenny had found himself preparing to show in the boy himself.

It was Cath Carter who had initially sought his advice: Cath who on several occasions now had invited him round supposedly to offer him tea and what she called a 'catch-up' but really to solicit his opinion on her daughter's ever-burgeoning collection of bruises and 'accidental' knocks. It wasn't like she hadn't a temper herself, she said, and she'd be a liar if she said she and Ed had never come to blows in all their years together, but this was different. He had overstepped a line. And whenever she had tried to broach the subject with Jessie, she had snapped at her to mind her own businesses, or words to that effect. 'Mothers and daughters, eh?' he had said, glibly. But there wasn't much he could offer. Cath believed the girl would be offended if she thought they were discussing her, so he wasn't allowed to approach her. It wasn't serious enough, she said, to call the police. In the old days, when he was growing up, a couple of the older men would go round and mark the boy's card, rough him up a li

ttle, just to let him know they were on to him. Most of the time it worked. But there was no Ed Carter around any more, no one outside the social services who was likely to want to take up this little issue. And there was no way Cath or Jessie would want that lot involved. So his hands were tied.

Until the boy turned up on his doorstep. Because no one had said anything, after all, about the two of them having a discreet word.

'You enjoying your new job, eh?'

'It's not bad, Father. Regular hours . . . Pay could be better.'

'Ah, now, there's a universal truth.'

The boy had looked at him, as if struggling to gauge his meaning, then lifted the heater with formidable ease, and carried it, as directed, into the front room, where he ignored the boxes of discount crockery and alarm clocks stacked high against the walls, partially obscuring two Virgin Marys and a St Sebastian. 'You want me to put it together for you? It'll take me five minutes.'

'That would be grand. I have no gift with a screwdriver. Shall I go and find one?'

'Got me own.' The boy had held it up, and Lenny had been suddenly uncomfortably aware of the strength in those shoulders, the potential force behind the now contained movements.

The irony was that he was not a bad lad: generally well thought of, polite, brought up on the good part of the estate. While not churchgoers, his parents were decent people. His brother, Lenny remembered, had taken himself abroad to do voluntary service. There might have been a sister, he couldn't remember. But the boy had never been in any trouble, had not been one of those he would occasionally scoop up from the market square in the early hours of Sunday, semi-conscious from cheap cider and God only knew what else. He had never been found racing stolen cars up and down the moonlit country lanes.

But that didn't mean he was good.

He stood, watching, as the metal legs were forcefully tightened to the body of the thing, the screws and nuts tightened with a spare efficiency. Then, as the boy grasped the heater, preparing to right it, Lenny spoke: 'So, how's your woman enjoying her new job?'

The boy did not raise his face from his work. 'She says she likes it.'

'It's a nice shop. Good to see something different in the town.'