by Jilly Cooper

‘Then you could have used the eye-gel,’ said Ferdie, sourly sweeping up dog biscuits. ‘Well, you screwed up that bloodstock account job.’

‘I’m desperately sorry, Ferd, I couldn’t just leave her. The other problem is basically my car’s been nicked. When I came out of her flat in Drake Street it had gone.’

‘Probably towed away.’ Ferdie was furiously crashing plates and mugs into the dishwasher.

‘It wasn’t. I stopped off at a champagne tasting at Oddbins on the way home. They let me use their telephone. Then I went to The Goat and Boots. That’s where I met Syd, that blind bloke. His guide-dog was incredible; she was called Bessie. You’d have loved her, Jacko.’

As he opened the kitchen door, Jack rushed out and an icy blast rushed in.

‘We’d better call the police about your car,’ said Ferdie.

‘Rachel was so pretty in a leggy sort of way.’ Lysander glanced at his watch. ‘Hell, I’ve missed Coronation Street.’ Going into the sitting room he switched on the television. ‘I must find out who won the 2.15. Where’s the remote control?’

But, as he up-ended a box of tapes on to the floor in an attempt to find it, Ferdie flipped.

‘Just shut up for once,’ he howled, ‘and go to fucking bed.’

6

Next morning Ferdie had to relent because Lysander woke up, as he so often did, crying for his mother.

‘Oh Ferd, I dreamt she was alive, the fog came down and I couldn’t find her.’

Dripping with sweat, reddened eyes rolling in terror, bedclothes thrown all over the sitting room, Lysander reached for a cigarette with a shaking hand.

Slumped in despair, he let the bubbles subside in the Alka Seltzer Ferdie brought him. The cartoons on TV AM which usually produced whoops of joy failed to raise a smile. He was too low even to switch over to Ceefax for the day’s runners and his horoscope.

‘What’s the point of Russell Grant rabbiting on about a romantic day for Pisces when I’ve got to go and tap Dad?’ He started to shake again.

Ferdie sighed. As Lysander’s car hadn’t been found and he’d promised to be at Fleetley, the public school in Gloucestershire where his father was headmaster, by eleven-thirty, Ferdie agreed to drive him down for a fee. Not that he’d ever get it, and he’d have to pretend to the office that he was out viewing properties.

‘You ought to get something inside you,’ he chided Lysander. ‘You haven’t eaten since yesterday morning.’

‘I feel sick.’

Lysander jumped at the telephone, always hoping it might be his mother and her whole death a terrible dream.

Picking up the receiver, Ferdie listened for a minute, before snapping: ‘He’s not here, and if he were, he wouldn’t have anything to say,’ and crashed it down again.

‘You’re going to feel even sicker. That was the Sun. Beattie Johnson’s dumped in The Scorpion. They’ll all be baying at the door in a second. We better move it.’

On top of The Financial Times and the Estate Agent’s Gazette, the newsagent on the corner placed a copy of The Scorpion.

‘Lover Boy’s in trouble again,’ he told Ferdie with a smirk. ‘Remind him he owes me sixty quid for mags and fags.’

‘I’m first in the queue,’ said Ferdie, grabbing a packet of toffees. ‘Oh my God!’

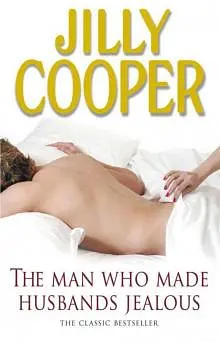

On the front of The Scorpion was a ludicrously, wantonly glamorous photograph of Lysander surrounded by foliage and wearing nothing but a flannel. ‘WHO COULD BLAME MARTHA WINTERTON?’ said the huge headline.

‘What the hell possessed you to pose virtually naked for Beattie Johnson?’ asked Ferdie as he got back into the car.

‘I was having a bath when she arrived,’ said Lysander sulkily.

Lysander, whom Ferdie described as the Geoffrey Boycott of reading, was still digesting the full horrors when the BMW shook off the remnants of rush-hour traffic and reached the M4.

‘Drop dead handsome,’ he read out laboriously. ‘And he nearly did when the bullets of Elmer’s guards rang out. Frozen in his tracks, Lysander could have passed for a statue of Adonis (who’s he?) in that moonlit garden!

‘“I aim to be a jump jockey,” says twenty-two-year-old Lysander, who should have no trouble with Bechers, if he can clear Elmer’s twenty-foot electric fence without a horse.

‘Oh Christ, it goes on about me being “the youngest son of David ‘Hatchet’ Hawkley, headmaster of Fleetley, one of England’s snootiest public schools (fees £12,000 a year). Perhaps Hatchet will give cheeky Lysander six of the best when they meet.”

‘Jesus, Beattie is a bitch,’ said Lysander furiously. ‘She promised she wouldn’t print any of the things I told her off the record. I’d have taken that Ferrari if I’d known. We’d better step on it before some do-gooder shows Dad The Scorpion. Thank goodness it’s banned at Fleetley. Dolly’s going to be livid, too. I feel seriously sick.’

He groped for a cigarette and was soon coughing his lungs out and dropping ash and toffee papers all over Ferdie’s very clean car.

‘That is the ultimate obscenity,’ he said disapprovingly as they got stuck in the fast lane behind a blonde in a Porsche going just below the speed limit, so Ferdie was forced to overtake on the inside.

‘Ought to be driving funeral cars.’ Lysander swung round to glare at her, then changed his mind. ‘Quite pretty though. Perhaps she’s just passed her test. Looks like that girl in the house next door. Did you ever bonk her?’

Ferdie nodded gloomily. ‘We had a bloody good four days while you were in Palm Beach. I even took her to San Lorenzo. Then she announced she was flying back to Australia to get married, and she’d only been practising on me.’

Ferdie told it as a big joke, but Lysander sensed the hurt. He longed for Ferdie to attract girls as effortlessly as he did.

‘Stupid cow,’ he said crossly, then to cheer Ferdie up, as they came off the motorway, ‘God, you shift this car. I’ve never done it this fast even at night.’

As they approached Fleetley through the bleak winter landscape with its patches of snow and icy wind flattening the pale grass on the verges, Jack started to snuffle at the window at familiar territory and Lysander grew lower and lower.

‘I can’t believe she won’t be here,’ he muttered, pulling Sherry’s blue baseball cap further over his nose.

He could never understand why his mother had stayed married to his stiff-upper-lipped, rigidly conventional, father. But, as a gesture of conciliation, he stopped in Fleetley Village to buy him a bottle of port and a packet of Swoop for his parrot, Simonides.

Fleetley School had once been inhabited by dukes. Now only the iron gates flanked by rampant stone lions and the avenue of towering flat-bottomed horse-chestnuts, and the great house itself, square, yellowy-grey and Georgian, remained. All round like mushrooms had sprung up classrooms, science labs, gyms and houses for masters and boys. The great lake had been turned into a swimming pool.

Nowhere for Arthur and Tiny to graze now, thought Lysander, gazing at the silvery-green stretches of playing field.

‘Oh no!’ He gave a whimper. The stables where he and his mother had kept their horses had already been flattened to make way for the new music school towards which, Mrs Colman, his father’s secretary, had helped raise £300,000.

‘You coming in?’ he asked Ferdie.

Ferdie shook his head: ‘I’ve got some calls to make.’

Although Ferdie had got straight As in four A levels, and David Hawkley had privately admitted he would be the first old boy to make a million, David had never forgiven his son’s best friend for flogging booze, cigarettes and condoms on the black market to other boys.

‘I’ll leave Jack with you then,’ said Lysander. ‘Simonides always gives him a nervous breakdown, imitating his bark. Christ, I hope Dad’s in a good mood.’

David Hawkley ran one of the best schools in the country. Nicknamed ‘Hatchet’ by the boys for the sharpness of his tongue, he was as brilliant a teacher as administrator, but tended ruthlessly to suppress the roma

ntic intuition which had made him the finest classical scholar of his generation. Extremely good-looking, pale, patrician, tight-lipped, like the first Duke of Wellington, with black Regency curls brushed flat and streaked with grey, he gave an impression of banked fires under colossal control – as though the battles of the Peninsula and Waterloo were being fought internally against despair and the powers of darkness.

Inflexible by nature, he had been particularly tough with his youngest son because Pippa, his late wife, had adored the boy so much. And Lysander was so agonizingly like Pippa with his wide-apart, blue-green eyes, which always opened wider when he was thinking what to say, the thick glossy brown hair falling over his forehead, and the sweet sleepy smile that totally transformed his face. Like Pippa he had the same air of helplessness, of not being responsible for his actions, of retreating into a dream world and laughing at all the wrong moments.

Lysander was so different from David’s older sons, Alexander and Hector, who, like their father, had got firsts at Cambridge, and were now doing brilliantly in the BBC and the Foreign Office. Both had made suitable marriages, and, unlike their father, hugged their children, cooked Sunday lunch, knew the difference between puff and shortcrust pastry, and changed nappies without any loss of masculinity. Like their father, however, they had endless discussions on what to do for and about Lysander.

Awaiting his son that morning, David Hawkley was in a particularly savage mood. Normally in January, he would have been basking in the glow of getting half the sixth form into Oxbridge. But such was the bias against public schools that this year only ten boys had scraped in and none of them with scholarships, resulting in endless recriminatory telephone calls from parents. Having been up most of the night, ruthlessly marking down Mocks papers, he didn’t think next year’s lot would fare any better.

His mood was even worse because a fox had killed his beloved parrot, Simonides, that morning. Simonides had barked at dogs, chattered away in Greek and Latin, and shouted ‘Fuck Off’, probably taught to him by Lysander, at parents who wouldn’t leave. He had also perched on David’s shoulders as he worked, hopped on to his bed, snuggling into his neck at dawn and been his only solace since Pippa died.

David was also livid because stories of Lysander’s Palm Beach exploits were plastered all over The Scorpion, which had been slyly left around by the boys – even on his pew in chapel.

Worst of all, Lysander in his vagueness had put the two letters he’d laboriously written in Palm Beach in the wrong envelopes. Thus instead of receiving a cheery note saying his son was getting on well and would visit him next month, David opened the letter Lysander had written to his highly dubious girlfriend, Dolly. This not only told her of the disgusting things Lysander was intending to do to her sexually when they met up again, but also how he would probably be forced to tap his battleaxe of a father and that he was sure his father in turn was keen on his secretary, ‘Mustard’, and what a dog she was.

David Hawkley was almost more outraged by the deterioration in Lysander’s spelling and grammar. But he was not prepared to hand the letter back with Sps in the margin, nor tell his son that the word ‘lick’ did not have two Ks, and that swuzzont-nerve certainly wasn’t spelt like that, nor ask what the hell was ‘growler guzzling’.

Icy with rage, David watched his youngest son getting out of a flash car, driven by that fat, deeply unsuitable friend, who should surely have been at work in some office. He then wandered up the path, wincing at the cacophony of the eleven-thirty bell, and stopped to stroke Hesiod, the school cat, who’d been shut out yet again by Mrs Colman, who didn’t approve of pets in the office.

It was Mrs Colman who had drawn David’s attention to The Scorpion first thing that morning.

‘I never read that beastly rag, but my Mrs Mop brought it in. I’m so sorry, David,’ – never ‘David’ except when they were alone.

Now orgasmic with disapproval, Mrs Colman was ushering Lysander into the study. Handsome, big nosed, high complexioned and hearty, she got quite skittish when Alexander or Hector visited their father: ‘Mr Hawkley, Mr Hector Hawkley to see you.’ But Lysander was too hauntingly like his mother, of whom Mrs Colman had been inordinately jealous.

Lysander noticed that ‘Mustard’ was very glammed up in cherry-red lambswool with matching colour on what could be seen of her pursed lips. Catching a discreet waft of Chanel No 5, he afforded her equal coolness.

‘Hi, Dad.’ He dumped the carrier bag on his father’s vast green-leather desk beside the neatly stacked Mocks papers. ‘The Swoop’s for Simonides.’

Timeo Danaos, thought David, peering into the bag. Unable to trust his voice not to quiver, he didn’t tell Lysander about Simonides, and merely said: ‘Thank you. You’d better sit down.’

For a man outwardly as bleak as the day, his study was an unexpectedly charming and welcoming room. Most of the wallspace was covered with books, well worn and thumbed in faded crimsons, blues, dark greens and browns, mostly in the original Greek and Latin, with their gold lettering glinting in the flames that glowed from the apple logs in the grate. Within reach were Aristotle’s Ethics and the seven volumes of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall. And because David Hawkley was not a vain man, tucked away on a top shelf were his own much-admired translations of Plato, Ovid and Euripides. He had been translating Catullus when Pippa died and had done no work on it since.

On the remaining walls were some good English water-colours, exquisite French engravings of Aesop’s fables, a photograph of the Headmasters’ Conference last year in Aberdeen, and yet another far more faded photograph of himself winning his blue at Cambridge, breast against the tape, dark head thrown back.

Over the fireplace was the Poussin of rioting nymphs and shepherds left to him by Aunt Amy, who had also left twenty thousand pounds to Lysander rather than his elder brothers because she felt the boy needed a helping hand. Lysander, to his father’s fury, had instantly blued the lot on a steeplechaser called King Arthur, who had promptly gone lame and not run since.

Unlike Elmer Winterton, David Hawkley believed in longevity, so the holes in the carpet were mostly covered by good rugs. The springs had completely gone in the ancient sofa upholstered in a dark green Liberty print to match the wallpaper. Mrs Colman kept urging him to replace the sofa with something modern, and relaxing, but David didn’t want parents to linger, particularly the beautiful, divorced or separated mothers – God, there were enough of them – who came to talk about their sons and ended up talking about themselves, their eyes pleading for a chance to find comfort in comforting him.

And now Lysander was sprawled on the same low sofa, huddled in Ferdie’s long, dark blue overcoat, re-adjusting his long legs, yet as seductive in his drooping passivity as Narcissus or Balder the Beautiful. But, modest like his father, he always seemed unaware of his miraculous looks.

David didn’t offer Lysander a glass of the medium-dry sherry he kept for parents, although he could have done with one himself, because he didn’t want any conviviality to creep in.

Lysander, who always had difficulty meeting his father’s cold, penetrating grey eyes, noticed he was wearing a new Hawkes tie, and that his black scholar’s gown, now green with age, was no longer full of holes where it had kept catching on door handles. His mother had only used needles to remove rose thorns, so the invisible stitches must be Mustard’s work, as was the posy of mauve and blue freesias on his father’s desk, whose sweet, delicate scent fought with the blasts of lunchtime curry drifting from the school kitchens.

There was a long, awkward pause. Lysander tried not to yawn. Noticing how the lines had deepened round his father’s mouth and how the dark rings beneath his eyes nearly joined his arched black brows, as though he was wearing glasses, Lysander felt a wave of compassion.

‘How are you, Dad?’

‘Coping,’ snapped David.

Then a pigeon landed on the window-sill and for a blissful second, David thought it was Simonides. Then, as reality reasserted itself, he channe

lled his misery into a furious attack on Lysander for sending the wrong letter.

‘How dare you refer to Mrs Colman in those offensive terms,’ he said finally, ‘after all she’s done for the school? Quite by chance, recognizing your illiterate scrawl, I opened the letter. Imagine the hurt it would have caused Mrs Colman if she’d seen it.’

Crossing the room, he threw the vile document on the fire, putting a log on top to bury it.

‘What the hell have you got to say for yourself? And take off that ridiculous baseball cap.’

Flushing like a girl, Lysander opened his eyes wide and launched into a flurry of apology.

‘I’m really, really sorry, Dad, I honestly am. Basically it’s very expensive living in London, and I honestly didn’t mean to upset you and Mustard . . . I mean Mrs Colman, but basically my car’s been nicked and I’d no idea Arthur’s vet’s bills were going to be so high, and I honestly promise to do better, and basically my attitude towards money is—’ He got to his feet to let in the school cat who was mewing piteously on the window-ledge.

‘Sit down,’ thundered his father.

‘But it’s freezing. Hesiod always came in when Mum—’ Then, seeing his father’s face, he sat down. He desperately needed some money. ‘As I was saying, basically my attitude—’

‘That’s enough,’ David interrupted him. ‘You have used the words basically and honestly about twenty times in the last five minutes. There is absolutely nothing honest about your promises to do better, nor basic about your attitude to money. You roll up here, plainly hungover to the teeth. You bring disrepute on the family getting your exploits plastered all over the papers. I hoped you would have learnt that no gentleman ever discusses the women with whom he’s been to bed.’

With a shudder, Lysander wondered if his father had bonked Mustard yet. The fumes of curry were really awful. He hoped the bursar had ordered a consignment of three-ply bog-paper to deal with it. Poor Hesiod was still mewing.

‘What is worse,’ went on his father, ‘is that in order to secure that job in the City – which I gather Roddy Ballenstein has already withdrawn – can’t say I blame him – I have been forced to admit the stupidest boy I have ever come across.’