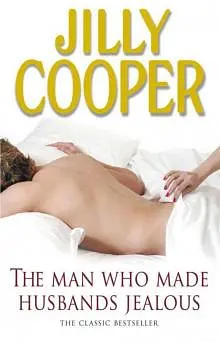

by Jilly Cooper

Georgie, still smarting because Rannaldini had dismissed ‘Rock Star’ as derivative, was even more livid that Guy hadn’t let her wash her hair. She’d had to make up in the car and now, in the crowded, overheated hall, was terrified that her pale skin would grow red and blotchy. She was also piqued that while everyone else’s children were crowding around asking for autographs, Flora, whom she hadn’t seen since before the American tour, hadn’t showed up.

Although she had only been at the school one term, Flora had already established herself as the Bagley Hall wild child, determined to buck the system. Wolfie Rannaldini had a massive crush on her, so did Marcus Campbell-Black, but he was too shy to do anything about it. Like most of the girls in the school, Flora had a massive crush on Boris Levitsky, who had sallow skin, wonderful slitty dark grey eyes and high cheek-bones. With his long blue jacket and shaggy black hair in a pony-tail, he would be perfectly cast as Mr Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty.

The concert had been due to start at five o’clock. It was now five-thirty, and there was still no sign of Rannaldini. The orchestra had tuned up and up. Parents were looking at their watches. Many of them had long drives home and would be forced to stumble out in the middle, ruining the concert, which was probably Rannaldini’s intention, thought Boris darkly. Determined to impress his old mentor, he was getting increasingly strung up. He was very tired, because sustained by vodka he was playing the fiddle in a Soho night-club to make ends meet.

Out in the hall, distraction was provided by the arrival of the great diva, Hermione Harefield, who’d just rolled up with Bob and plonked herself down between Kitty and Guy in the seat that was being kept for Rannaldini. It was twenty-five to six. Miss Bottomley, the headmistress, vast and Sapphic, had just risen furiously to announce that the concert could be delayed no longer, when Rannaldini’s helicopter landed on the lawn outside, squashing a lot of daffodils. Kitty watched him jump down like a cat, bronzed and impossibly glamorous, with his thick pewter hair hardly ruffled by the wind, and her heart failed, as it always did. Georgie, prepared to detest him because of Hermione’s jibes, thought he was the most attractive man she had ever seen. It was not just the good looks, but the total lack of contrition.

‘Sorry to hold you up, Sabine,’ he called out blithely to an apoplectic Miss Bottomley, as he swept up the aisle asphyxiating everyone with Maestro. ‘We had engine trouble.’ Then, glancing up at Boris, who was fuming in the wings, ‘Carry on, Boris.’

Always engine trouble when Cecilia’s in town, thought Kitty despairingly.

‘Over here, Rannaldini. We’ve saved you a seat,’ called Hermione in her deep thrilling voice.

In fact she hadn’t. It merely meant that Helen Campbell-Black had to move into the row in front and sit next to her ex-husband, Rupert, who had in the past been infinitely more promiscuous and far later for every engagement than Rannaldini, but who was now glaring at him with all the chilling disapproval of the reformed rake.

‘Fucking Casanouveau,’ he murmured to Taggie. ‘Can’t imagine him as a schoolboy. Must have spent his time in the biology lab dissecting live rats.’

Moving down the row to join Hermione, Rannaldini’s eyes fell on a cringing Kitty.

‘Friday is a work day,’ he murmured as he sat down beside her. ‘I assume everything’s in order at home for you to play truant like this.’

‘I fort you was coming tomorrow,’ stammered Kitty. ‘I fort Natasha would like one of us to be here.’

‘Hush,’ said Hermione loudly, ‘Boris wishes to begin.’

Boris had a hole in his dark blue jacket, buttons off his white frilled shirt, a nappy pin holding up his trousers, and his unruly black hair was escaping from its black bow. Mounting the rostrum, he bent to kiss the score of Brahms’ Academic Overture, lifted his stick and began immediately. If Rannaldini was all icy precision, Boris was all fire and romantic enthusiasm. The orchestra played as though they were possessed. Bob Harefield, who never stopped talent-spotting and was now leaning against the wall at the back of the hall, took out his notebook.

Rannaldini, on the other hand, closed his eyes and ostentatiously winced at any wrong note. Rupert Campbell-Black was not much better behaved, his golden head lolling on his present wife’s shoulder as he gently snored in counterpoint to the music, until his ex-wife woke him up to listen to Marcus playing the last movement of Mozart’s E Flat Piano Concerto. This Marcus did so exquisitely, and looked so touching, with his faun’s face, big hazel eyes and gleaming dark red hair, that the audience, despite being kept late by Rannaldini, demanded an encore.

Mopping his brow, looking much happier, Boris tapped the rostrum.

‘Marcus will now play a little composition of my own. I ’op you all like him.’

The audience wasn’t sure, and started looking bewildered and at their watches, not understanding the music one bit.

‘Sounds as though the stable cat’s got loose on the piano. Awful lot of wrong notes,’ muttered Rupert.

‘I think they’re meant to be, because it’s modern,’ whispered Taggie.

‘Hush,’ said Rupert’s ex-wife furiously.

Rannaldini, who’d repeatedly refused to programme Boris’s music, felt totally vindicated, and smirking, pretended to go to sleep again. Through almost closed eyes he was aware of Kitty, plump, white and quivering like a blancmange. It was cruel to compare her with the other very young wife in the room, but Rannaldini did so. Staring at Taggie Campbell-Black, he decided she was very desirable, particularly in that red cashmere polo-neck which had brought a flush to her cheeks. And what breasts, and what legs in that black suede mini-skirt! Her succulent thighs must be twice as long and half the width of Kitty’s. She was reputed to be a marvellous cook, and to be adored by all Rupert’s children, which was more than could be said for Kitty. How amusing to take Taggie off Rupert, thought Rannaldini, who liked long-distance challenges. As if willed by his lust, Taggie turned round and smiled without thinking because he looked familiar. Then, realizing they hadn’t been introduced, she turned away, and Rannaldini suddenly encountered such a murderous glare from Rupert that he hastily looked up the row at Helen. She was stunning, too. Rupert certainly knew how to pick them. Rannaldini wished he had brought Cecilia to redress the balance, but he had exhausted her so much at The Savoy she couldn’t be bothered to get out of bed.

And now it was Natasha’s turn to sing ‘Hark, Hark the Lark’. Her voice was strident and she hadn’t practised enough. Marcus played the accompaniment, and, being a kind boy, speeded up to get her through the difficult bits. The audience, who didn’t know any better, seeing in their programme that she was a Rannaldini, gave her huge applause, led by Hermione.

Rannaldini let his thoughts wander to the little blond flautist he had reduced to tears at the rehearsal. Tomorrow he would be stern at first, then stun her with a word of praise and ultimately ask her to his flat in Hyde Park Square for a drink. ‘I only bully you, dearest child, because you have talent.’

The orchestra, with Wolfie playing the clarinet, Natasha the violin and Marcus Campbell-Black the trumpet, were just murdering the ‘Dove’ from Respighi’s The Birds, and plucking the poor thing as well, and Rannaldini was about to stage another of his very public walk-outs which would take all the attention off Boris, when Kitty whispered that the girl Wolfie was mad about was coming on next.

The orchestra, who were going to end the concert with an Enigma Variation, stayed in their seats. Rannaldini couldn’t imagine his stolid rugger-playing son being mad about anyone interesting, but when Flora strolled on to the platform, he couldn’t take his eyes off her. Despite having several spots, greasy red hair the colour of tabasco and a pale green complexion from drinking at lunchtime, she was the sexiest girl he’d ever seen. Her school shirt, drenched in white wine, clung almost transparently to her small jutting breasts, her tie was askew, her black stockings laddered. Gazing truculently at the back of the hall she sang ‘Speed Bonny Boat’ unaccompanied and the room went s

till. Her voice was beyond criticism, sweet, pure, piercingly distinctive and delivered in a take-it-or-leave-it manner without a quiver of nerves. Her star quality was undeniable. Georgie clutched Guy’s hand. Deeply moved, Guy couldn’t resist glancing sideways, delighted at the dramatic effect his daughter’s voice was having on Rannaldini. He didn’t want her to become a pop star, but a career in classical music would be different. Perhaps Flora was learning to behave at last.

But when Flora reached the line about winds roaring loudly and thunderclouds rending the air, she so empathized with tossing on a rough sea that she suddenly turned even greener, and, grabbing the nearest trumpet from a protesting Marcus, threw up into it.

The first person to break the long and appalled silence was Rupert Campbell-Black, quite unable to control his laughter.

Sod Wolfie, thought Rannaldini with a surge of excitement, I must have that girl.

Georgie and Guy were so overwhelmed with mortification and, in Guy’s case, white-hot rage that they nearly boycotted the drinks party afterwards. Miss Bottomley, who’d been looking for an excuse all term, was poised to sack Flora on the spot when Rannaldini glided up and smoothed everything over.

Putting his beautiful suntanned hand, which was immediately shrugged off, on Miss Bottomley’s wrestler’s shoulders, he assured her that all creative artists suffered from stage fright.

‘The girl’s impossible,’ spluttered Miss Bottomley.

‘But on course for stardom. I never ’ear a voice like this since I first heard Hermione Harefield. Even Mrs Harefield,’ Rannaldini lowered his voice suggestively, ‘need endless coaxing to go on and very delicate handling.’

Frightfully excited at the thought of handling Hermione, Miss Bottomley agreed to give Flora another chance.

‘I will speak to her parents,’ insisted Rannaldini.

He then astounded Wolfie, Natasha and Kitty by changing his mind and staying on for the drinks party. As Rupert Campbell-Black had led the stampede of cars down the drive, he would at least have the floor to himself.

‘Was “Hark, Hark” OK, Papa?’ demanded Natasha, linking arms with her father as she led him down dark-panelled corridors past gawping staff and pupils.

‘Excellent,’ said Rannaldini abstractedly, ‘you’ve come on a lot. What was the matter with Wolfie’s little redhead?’

‘Flora?’

Deliberately Natasha let the door into Miss Bottomley’s private apartment slam in the face of Kitty, who was panting to keep up with them on her high heels.

‘Flora got pissed at lunchtime,’ explained Natasha. ‘She’s got this massive crush on Boris Levitsky and she saw him French, or rather,’ Natasha giggled, ‘Russian-kissing some strange blonde – not Rachel his wife – outside the Nat West this morning. That was Boris’s trumpet Flora was sick into. Boris had lent it to Marcus.’

So Boris is back with Chloe the mezzo, thought Rannaldini. Certainly he didn’t regard Flora’s massive crush on the Russian as any competition.

Miss Bottomley’s large study was already packed with parents falling on drink and food like the vultures culture always seems to turn people into. Most of them, Rannaldini noticed scornfully, seemed to be gathering like flies on a cowpat round that ghastly, blousy Georgie Maguire, who kept throwing him hot glances. Ignoring her totally, but accepting a glass of orange juice – he never touched cheap wine – Rannaldini spoke briefly to Boris.

‘Well tried, my dear. Slightly too ambitious. They are still cheeldren, and was it wise to programme one of your own compositions in front of these Pheelistines?’

Boris, whose conducting arm was not aching too much to prevent him downing several glasses of red, wanted to smash Rannaldini’s cold, fleshless, but curiously sensual face, but then Rannaldini murmured something about having a pile of freelance work. Boris needed the money badly.

‘Now introduce me to Flora’s parents,’ he said to Natasha.

‘Oh, didn’t you twig, Papa? Flora’s Georgie Maguire’s daughter.’

Rannaldini didn’t miss a beat. Gliding forward, parting parents like the Red Sea by sheer force of personality, he stopped in front of Georgie, put his hands in the pockets of his soft brown suede jacket, bowed slightly and glared aggressively into her eyes. His trick was to unnerve women by staring them out, then suddenly to smile.

‘Senora Seymour,’ he said caressingly. ‘May I call you Georgie?’ Then raising her hand which was clutching a soggy Ritz cracker topped with tinned pâté and chopped gherkin, he touched it with his lips.

Just one corny-etto, thought Guy.

‘I am sorry I mees your launching,’ went on Rannaldini, ‘I ’op it is not too late to say: welcome to Paradise.’

‘Oh, not at all. How lovely to meet you at last.’ Georgie was totally flustered, as though a great tiger had strolled out of the jungle and was rubbing his face against her cheek. Rannaldini was even more faint-making close up.

‘And I loff Rock Star. It is great music and your peecture don’t do you any justice.’

What could Rannaldini be playing at? Hermione, who’d joined them, was looking furious.

‘Oh, thank you,’ gasped Georgie, then remembering her manners, ‘This is Guy – my husband,’ she added almost regretfully.

‘I haff heard much of your gallery.’ Rannaldini switched his searchlight charm on to Guy. ‘You were first to exeebit Daisy France-Lynch when no-one else had ’eard of her. I ’ave several of her paintings.’

‘Oh, right,’ Guy was totally disarmed. ‘I’d love to see them.’

‘You shall,’ said Rannaldini. ‘First I want to get Bob over to talk about Flora.’

Seeing his endlessly compassionate and good-natured orchestra manager making too good a job of cheering up Boris Levitsky, Rannaldini clicked his fingers imperiously.

Refusing to be ruffled, Bob finished what he was saying and was fighting his way through the mob when Guy said to Rannaldini: ‘You may not have been here to welcome us, but Kitty has been an absolute brick, bringing us new-laid eggs and turning down curtains. You’re a lucky man,’ he added rather heartily, aware that the searchlight beam had dimmed a little.

Rannaldini, who detested Kitty furthering anyone’s interests but his own, much preferred it if she turned down invitations rather than curtains. He even begrudged her taking an hour off on Sunday to go to church.

Aware of a distinct chill but not understanding why, Georgie couldn’t bear to lose contact.

‘We wanted to take Kitty out to The Heavenly Host tonight,’ she stammered.

‘Why don’t we all go? We were planning to celebrate Flora’s first night home, although on second thoughts she seems to have pre-empted us rather too well already. Why don’t you both come to dinner at Angel’s Reach? How about Friday week? We should be a little less shambolic by then.’

Hermione, who was about to draw Georgie aside and explain that the protocol in Paradise was for long-term residents to invite first, awaited one of Rannaldini’s legendary put-downs.

Instead, to her amazement, he accepted with enthusiasm.

On four glasses of cheap wine, Georgie proceeded to invite Bob, who’d just brought Boris over to be introduced, and Hermione who only accepted because Rannaldini had. Then she asked Boris and his wife Rachel, if they were in the country, to make up for the sick trumpet, which Boris reassured Georgie would easily wash out. Then, to placate Miss Bottomley, she asked her as well.

‘Best time to have a house-warming party when it’s not all done up for people to ruin,’ said Georgie happily.

As they drove home, a moon one size up from new was winging its way like a white dove towards a dying flame-red sunset. Slumped in the back Flora was fast asleep.

‘I thought you wanted peace and quiet in the country,’ chided Guy.

‘I got carried away. I thought it would be good for Flora to meet Rannaldini. She needs an older man to direct her. One never listens to one’s parents at her age. He says she’s exceptional. Anyway I can’t cut mys

elf off completely. We can have sausages and mash. People will only expect a picnic as we’ve just moved in.’

Guy, who knew he’d be lumbered with the cooking and the organization, put his mind to the menu.

Georgie lay back in a blissful haze, convinced Rannaldini had only accepted because he fancied her. It was years since she’d felt that loin-churning excitement.

‘Rannaldini’s lovely, isn’t he?’ she couldn’t help saying.

‘Not terribly,’ said Guy shortly. ‘Not to Kitty and he’s clearly terribly two-faced.’

But it was such a beautiful face, thought Georgie dreamily, you didn’t mind there being two of them.

18

Guy was an ace cook and a wonderful host, but Georgie had never known him make such a fuss about a dinner party. His nose had been in Anton Mosimann for days. As the dining room was still being wallpapered, he took the Friday of the dinner party off and set the big scrubbed table in the kitchen first thing in the morning. He then got enraged when Charity the cat did bending races in and out of the glasses, decanters and flowers, and with Flora when she drifted in at lunchtime with a group of friends and started making toasted sandwiches and leaving a trail of mugs, crumbs and overflowing ashtrays.

‘We met a crowd of spiders fleeing down the drive singing the theme from Exodus,’ Flora told her father. ‘You ought to put one in a glass case to remind us what they look like.’

‘Don’t be fatuous,’ snapped Guy, bashing a lobster claw with unusual violence.

When he wasn’t cooking Guy seemed to spend the whole day cleaning surfaces, tidying and re-arranging the house, and disappearing to get petrol for the mower.

Every superfluous blade of grass must be cut, like a woman waiting for her lover, thought Georgie, who, having been told she was more hindrance than help, retired to work.

She was enchanted with her new study, high up in the west tower and reached by a staircase so narrow they had to hoist her piano, her worktable and Dinsdale’s ancient chaise-longue in through the window. Sitting at her table, pen poised over a blank page of manuscript paper, she was trying to write a song equating love to everlasting candles on a birthday cake.