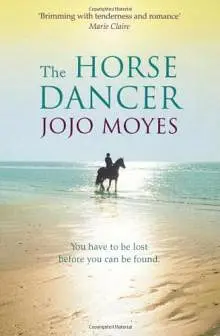

by Jojo Moyes

'He trusted us.'

He sat on the bed beside her. 'Yes, but . . .'

'You were right. It's all my fault.'

'No . . . no . . .' he murmured. 'It was a stupid thing to say and I shouldn't have said it. It's not your fault.'

'It is,' she insisted, her voice distorted by tears. 'I let him down. I let her down. I never looked after her like I should. But it was too . . .'

'You did fine. Like you said, you did your best. We both did our best. We weren't to know this would happen.'

He was astonished that something he had said could provoke such a reaction in her. Natasha had long seemed impervious to anything he did. 'Hey, come on, it was just words . . . I was angry . . .'

'No. You were right. I shouldn't have walked out. If I'd stayed . . . perhaps made her open up to me a bit more . . . But I couldn't be around you. I couldn't be around her.'

He could see her thin arms in the red shirt, smeared with the inky marks of her tears. He wanted to reach out a hand to her, but he was afraid that if he did she might close herself off again. 'You couldn't be around Sarah?' His voice was quiet, careful.

Her face was still now, the sobs subsided. 'She showed me I would never have been any good at it. Having Sarah there made me see . . . that perhaps there was a reason I never had children.' She swallowed hard. 'And what's happened to her since shows me I was right.' Her voice broke, and she was sobbing again, shaking, her body suddenly diminished.

Mac was stunned by her sudden grief for their lost babies. 'No, Tash,' he said quietly, reaching for her hand now. Her fingers were wet with tears. 'No . . . No, Tash. That's not it . . . Come on . . .' he protested, his own voice catching on the words. He pulled her close to him, put his arms around her, rocking her, hardly knowing what he was doing. 'Oh, Christ. No . . . you would have been a great mother, I know you would.'

He rested his face on the top of her head, breathing in the familiar smell of her hair, and realised that the tear sliding down his cheek was his own. And he felt his wife's arms creep around him so that she clung to him, a silent message that perhaps he had been needed, wanted, that he had had something to offer her, after all. They sat in the dark, holding each other, grieving, too late, for the children they had lost, the life together they had relinquished. 'Tash . . .' he murmured. 'Tash . . .'

Her sobs quieted, and in their place, unspoken, a question filled the air around them, became written in their skin where it touched. He lifted her face in his hands, her bruised eyelids, her damp skin, trying to read her, and saw something in it that made thought disappear.

Mac lowered his face to Natasha's and, with a low murmur, kissed her bottom lip, his hands tracing the planes of her face, strange yet familiar. For a moment, he felt her hesitate, and some distant part of him stalled too - What is this? Do we stop? - but then her slim fingers were clamped around his own, delicate animal sounds escaping her as her lips sought his.

And Mac was pressing her down, a sigh of relief and desire escaping him. He kissed her neck, her hair, fumbled with the buttons of her crumpled blouse, smelt the musk of her skin and became clumsy with desire. He felt her legs hook around his back, and observed, with some distant, still-thinking part of him, that she had never been like this. Not for years. That this Natasha was someone new, and his feelings about this were more complicated than he could begin to deal with.

He opened his eyes and looked down at her in the faint light from the window, the smeared mascara, the unwashed hair, the faint pulse in her arched, pale throat, and the tenderness he had felt was smothered by something dark and male. It answered something in him that he had not been able to acknowledge to her in the days of their marriage. This was not a matter of retreading old ground. This was not someone he even recognised.

'I want you.' He heard her voice in his ear as if it were a surprise to her, husky with something of her own, something greedy and desperate. 'I want you,' she said again, and Mac, pulling his shirt over his head, understood that although it had not actually been a question there was only one possible answer.

Twenty-five

'The rider himself is in extreme danger if anything happens to his horse.'

Xenophon, On Horsemanship

A white bird was circling above her; it moved in huge, lazy circles, emitting a droning hum that grew louder and then, when the noise became unbearable, receded. Sarah blinked, unable to distinguish it clearly against the bright light behind it, pleading with it silently to quieten.

She lay very still as the noise grew in volume, and this time the ground vibrated beneath her so that she frowned, conscious of the pain in her head, in her right shoulder. Please, she willed it, no more. It's too loud. Her eyes screwed shut against it, this brutal invasion of her senses. Finally, as it became unbearable, the noise stopped. She felt a vague gratitude, before it was interrupted by a different kind of noise. A door slamming. An exclamation.

Ow, she thought. My shoulder. Then: I'm so cold. I can't feel my feet. The light was dimmed and she opened her eyes a fraction to see a dark shape looming above her.

'Ca va?'

Panic took hold even before her conscious self had understood why. Something was wrong, very wrong. She blinked, the pain forgotten as she made out the shape of a man staring down at her. She discovered she was lying in a drainage ditch. She clawed herself upright, scrambling backwards until she met a concrete post.

Men. Motorbikes. Terror.

The farmer stood a few yards from her, his face concerned, his huge yellow agricultural machine a short distance away, its door hanging open where he must have jumped down.

'Que faire?' he said.

Sarah's eyes refused to focus. She glanced around, beginning to make out the expanse of ploughed field, the distant sheds of the industrial estate. The industrial estate. A leap into the dark.

'My horse,' she said, jumping to her feet and letting out an involuntary yelp of pain. 'Where is my horse?'

The farmer was backing away, gesturing at her to stay where she was. 'Je telephonerai aux gendarmes,' he said. 'D'accord?'

She was already stumbling forwards, along the road, trying to clear her head, her vision. 'Boo!' she shouted. 'Boo!'

She didn't see the farmer's suspicion as his thick, square fingers hesitated on the buttons of his mobile phone. If she had, she might have read it. Drugs? it said. Madness? There was mud all down one side of her, a bruise on her face; some kind of trouble?

'Tu as besoin d'aide?' he said, cautiously.

She did not hear him.

'Boo!' she shouted, clambering on to a concrete post, wincing as she tried to keep her balance. Her body ached; her vision refused to clear. But even she could see that the fields were empty, except for a few distant crows, the steam of her breath. Her voice simply disappeared into the still morning air.

She turned back to the man. 'Un cheval?' she pleaded. 'Un cheval brun? Un Selle Francais?' She was trembling; a mixture of cold and fear. This couldn't be happening. Not now, not after all this. Fear gripped her hard, shaking her awake, incapacitating her with the enormity of what had happened. It was too big a thing, too terrible a prospect. He could not have gone. Of course he could not have gone.

The farmer was standing by the door of his machine now. 'Tu as besoin de mon aide?' he said again, less keen somehow this time, as if hopeful that this foreigner would announce that, no, she was fine.

In fact Sarah, already limping down the road, not sure where she was going to look first, was too busy shouting her horse's name to hear him. The sheer blinding shock of Boo having gone overrode the pain she could feel in her shoulder, the repetitive hammering in her head.

She had walked almost the whole length of the ploughed field before she realised that her horse was not the only thing that was missing.

Almost thirty miles away, Natasha also woke to an unexpected sense of absence. Even before she worked out that the sound she had heard was Mac disappearing into the bathroom, she had been aware of the loss of his

body beside hers. She still felt the weight of his arm across her, the solid length of his leg pressed into the back of hers, his breath warm on her neck. Without him she was untethered, as if she was floating loose in space instead of tucked cosily into a vast double bed. Mac.

She heard him lift the loo seat and allowed herself a small smile at this indication of domesticity. She burrowed deeper under the covers, lost in the fug that told of hours of pleasure, of desire met and reciprocated. She thought of him, of his lips on her, his hands, his weight, the intensity in the way his eyes had examined her, as if all the previous year had not been washed away but made irrelevant by the strength of their feelings. She thought of her own actions, her lack of inhibition, the desire, this thing, that had sprung so unexpectedly, as if it were quite separate from who she had thought she was. It was as if their past arguments, their cruelties, the things that had kept them from being themselves with each other, had heightened everything. She had surprised him, she knew, and she had surprised herself. How long had it been since she had felt like the better version of herself in his eyes?

She slid over to his side of the bed, breathing in the still warm imprint of his skin. She heard the lavatory flush, the sound of running water as he washed his hands. Would it be wrong to wrap herself around him again before they got up and restarted the search? Would it be wrong to use his lips, his hands, his skin, to fortify herself against the day ahead? What would it feel like to bathe in that huge, claw-footed bath, to reclaim that strong body as hers, inch by soapy inch? I love him, she thought, and the knowledge came as a relief, as if to admit it meant she could stop struggling.

She sighed with contentment. Then, prosaically, she rubbed her eyes, conscious of the mascara smears of the previous evening, tried to smooth her hair, which was matted at the back of her head. Her body glowed, prickled with anticipation and she urged him silently to hurry. She wanted him against her, around her, inside her. She felt a hunger for his physical self that she had thought did not exist in her any longer. She never felt like this with Conor. She had felt physical desire, yes, but it had been like quenching an appetite they both acknowledged, rather than this giddy, visceral feeling of being one half of a whole, of feeling even a temporary absence like an amputation.

It was at that point that she heard the voice. At first she had thought it was someone out in the corridor, but as she lay, straining to hear, she realised Mac was talking. She climbed out of bed, wrapping the bedspread around her, padded barefoot to the bathroom door, hesitated for a moment, then rested her ear against the old oak panel.

'Sweetheart, let's talk about this later. You - you're impossible.' He was laughing. 'No, I don't . . . Maria, I'm not going to have this discussion now. I told you, I'm still looking. Yes, I'll see you on the fifteenth . . . Me too.' He laughed again. 'I've got to go now, Maria. I'll speak to you when I'm home.'

For years afterwards, Natasha would struggle to disassociate a smell of beeswax from a premonition of disaster. She backed away from the door, the smile gone, the glow transformed as if by alchemy into ice in her blood. She had just made it to the bed when he emerged from the bathroom. She slowed her breathing, rubbed her face, unsure how to appear to him.

'You're awake,' he observed. She could feel his eyes on her. His voice was roughened by lack of sleep.

'What's the time?' she asked.

'A quarter past eight.'

Her heart was beating uncomfortably inside her chest. 'We'd better get going,' she said, casting around on the floor for her clothes. She didn't look at him.

'You want to get up?' He sounded surprised.

'I think it would be a good idea. We have to speak to the police, remember. Madame . . . was going to ring them for us.' She could see her knickers under the great walnut chest of drawers. She flushed at the thought of how they had ended up there.

'Tash?'

'What?' She pulled them on, her back to him, the bedspread hiding her naked body from him.

'Are you okay?'

'I'm fine.' She wrestled the knickers over her hips and turned to him. She kept her gaze bright, neutral. Behind it she wished him a slow, painful death. 'Why? Shouldn't I be?' He was trying to read her mood. He smiled, shrugged, a little uncertain.

'I just think we should get on,' she continued. 'Remember what we're doing here.' And before he could say anything, she had grabbed her things and was headed for the bathroom.

The gendarme had spoken to the administrative staff at Le Cadre Noir before he had come to the chateau.

'There have been no reports of such a girl here,' he said, as they sat in the drawing room over coffee provided by Madame, who had retired to a discreet distance, 'but they have assured me they will certainly let you know should she arrive. Will you be staying on?'

Natasha and Mac glanced at each other.

'I guess so,' said Mac. 'This is the only place Sarah's likely to come to. We'll stay until she gets here.'

Their story had prompted the same response in the policeman as it had in Madame: faint disbelief, the query hanging in the air as to how would-be parents could tolerate the idea of a child travelling so far alone. 'May I ask why you think she would head for Le Cadre Noir? You are aware that it is an elite academy?'

'Her grandfather. He was a member, or whatever you call it, a long time ago. It was he who seemed to believe that she would come here.'

The inspector seemed satisfied with that response. He scribbled a few more notes in his pad.

'And she has been using my credit card. We know that it has been used en route in France,' Natasha added. 'All the indications are that she is headed this way.'

The policeman's expression revealed nothing. 'We will place the gendarmes within a fifty-mile radius on alert. If anyone sees her, we will let you know.' He shrugged. 'It will not be easy, though, to distinguish one young woman on a horse around here - you must understand that in a place like Saumur we are surrounded by people on horseback.'

'We do understand,' said Natasha.

After the policeman had left, they were silent. Natasha gazed around the room at the heavy drapes, the stuffed birds in glass cases.

'We could drive around,' he said. 'I guess it's better than sitting here all day. Madame said she would ring if anything happened.' He made as if to touch her arm, but Natasha moved away, busying herself with her bag.

'I don't suppose it makes sense for both of us to travel,' she said. She wanted to punch him when he wore his vaguely hurt expression. 'I'll have a walk around the academy. You go. We'll keep in touch.'

'That's ridiculous. Why would we split now? Natasha, we'll go together.'

There was a brief pause. She gathered up her things, refusing to look at him. 'Okay,' she said finally, and left the room.

There were hoofprints at the far end of the ploughed field. She had tried to run across it, spying them, but a thick collar of mud, sticky and heavy, had attached itself to her boots, making all but the slowest movement impossible. Finally, she had reached the end, but after a few muddy clods on the tarmac, Boo's trail had disappeared.

She walked for another hour, zig-zagging across the fields, wandering into copses, her voice hoarse from shouting, until she found herself in the next village. By then she was shaking, her body chilled and empty. Her shoulder ached, her stomach was gripped by hunger pangs. Cars sped past her, not noticing or not caring, occasionally sounding a horn if she ventured too close to the road.

It was as she reached the village that she saw the little row of shops. The scent of bread from the boulangerie was rich and comforting, completely out of reach. She thrust a chilled hand into her pocket, and came up with three coins. Euros. She couldn't remember why they might be there: Thom had put her money in an envelope into her missing rucksack. Change. From some brief transaction the previous day. She stared at the coins, at the boulangerie, and then at the telephone box in the square opposite. Everything was gone: her passport, Boo's papers, her money, Natasha's credit card.

The

re was only one person who might be able to help her. She reached into her inside pocket for the photograph of Papa; it was crumpled, and she tried to straighten it with her thumbs.

She walked stiffly across the square, went into the bar tabac, and asked for a telephone. 'Tu as tombe?' the woman behind the bar said sympathetically.

Sarah nodded, suddenly aware of her clothes, the mud. 'Pardonnez moi,' she said, checking that she had not left a trail of footprints.

The woman was staring at her face, frowning in concern. 'Alors, assaies-toi, cherie. Tu voudrais une boisson?'

Sarah shook her head. 'English,' she said, her voice barely rising above a whisper. 'I need to call home.'

The woman eyed the three coins in Sarah's hand. She reached out a hand and touched the side of her face. 'Mais tu as mal a la tete, eh? Gerard!'

A few seconds later a moustachioed man appeared behind the bar, clutching two bottles of a cherry-coloured syrup, which he placed on the bar. The woman muttered to him, gesturing towards Sarah.

'Telephone,' he said. She rose, made for the public phone, but he shook his finger. 'Non, non, non. Pas la. Ici.' She hesitated, unsure it this was safe, but decided she had little choice. He lifted the bar and shepherded her through to a dark hallway. A telephone stood on a small chest of drawers. 'Pour telephoner,' he said. When she held out her coins, he shook his head. 'Ce n'est pas necessaire.'

Sarah tried to remember the code for England. Then she dialled.

'Stroke Ward.'

The sound of an English voice had an unexpected effect: it made her suddenly homesick. 'It's Sarah Lachapelle,' she said, her voice tight. 'I need to speak to my grandfather.'

There was a silence. 'Can you hold on a moment, Sarah?'

She heard murmuring, the kind that takes place when someone puts a hand over the receiver, and glanced anxiously at the clock, not wanting to cost the French couple too much money. She could see the woman through the doorway, serving someone coffee, talking animatedly. They were probably discussing her, the English girl who had fallen from her horse.

'Sarah?'

'John?' She was thrown by his voice, having expected a nurse.

'Where are you, girl?'