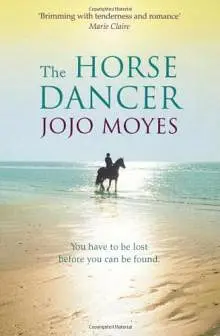

by Jojo Moyes

'It just seems weird, the idea of someone else being in there. They won't know about any of it - about the reclaimed wood banisters or why we put that round window in the bathroom . . .'

Mac seemed suddenly lost for words.

'All that work. And then nothing. We just move on.' She was aware that the wine was prompting her to say too much and was somehow unable to stop herself. 'It feels . . . like leaving a piece of yourself behind.'

He met her eyes, and she had to look away. On the grate, a log shifted, sending a burst of sparks up the chimney.

'I don't think,' she said, almost to herself, 'that I could put that much work in somewhere else.'

Upstairs she heard Sarah opening and closing a drawer against the dull crackle of the fire.

'I'm sorry, Tash.' He hesitated, then reached across and took her hand. She stared at their fingers, intertwined. The strange, yet familiar feel of his skin on hers knocked her breath from her chest.

She pulled away, her cheeks colouring. 'This is why I don't drink very often,' she said, and stood up. 'It's been a long day. And I suppose everyone feels like this when they sell somewhere that they've spent a long time in. But it's just a house, right?'

Mac, face revealed nothing of what he was thinking. 'Sure,' he said. 'It's just a house.'

Twelve

'The gods have bestowed on man, indeed, the gift of teaching man his duty by means of speech and reasoning, but the horse, it is obvious, is not open to instruction by speech and reasoning.'

Xenophon, On Horsemanship

Despite her exhaustion, Natasha slept fitfully. The silence of the countryside seemed oppressive, the proximity of Mac and Sarah too great in the confines of the cottage. Downstairs, she could hear the creak of the sofa when he shifted, the diplomatic pad of bare feet to the bathroom as Sarah crept to the loo in the small hours. She thought she could even hear them breathing, and wondered if that meant Mac could hear every move she made too. She slept, and woke from brief, fitful dreams of arguments with him, or hallucinatory imaginings that strangers invaded her home, until finally, as the blue light and Arctic orange sun rose above the distant trees, she stopped trying to force her eyes shut. A kind of peace descended, as if her mind had been persuaded by physical circumstance to be still. She lay there, staring at the lightening ceiling, until she pulled on a dressing-gown and climbed out of bed.

She wouldn't think about Mac. Allowing herself to get upset about the house was foolish. Dwelling on the touch of a hand was the road to madness. She had been drunk and had let down her guard. God only knew what Conor would have said if he had seen her.

She checked the time - a quarter past six - then listened for the dull roar that would tell her the central-heating timer had kicked in. She gazed at her closed bedroom door, as if she could see through it to where Sarah lay sleeping on the other side of the landing.

I've been selfish, she thought. She isn't stupid, and she can sense my discomfort. How must it feel to have lost so much, to be so dependent on strangers? Money, her age, her background gave Natasha choices that Sarah might never have. For the next few weeks, she resolved, she would be friendlier, disguise her inbuilt reserve and distrust. She would make this short stay useful. A small act, but a worthy one. If she focused more on Sarah, she might be less diverted by Mac's presence. She might be able to prevent herself ending up in the situation she had last night.

Coffee, she decided. She would make coffee and enjoy an hour's peace.

She opened her bedroom door as silently as she could and stepped out. The spare-room door was ajar, and Natasha stared at it for a moment before, on a whim, stepping forward and pushing gently against it. This was what mothers did, she told herself. All over the world mothers were pushing bedroom doors to gaze at their sleeping children. She might feel a little of what they felt. Just a little. It was somehow easier to feel something, to try to feel something, when the girl was asleep.

She was interrupted by the shrill ring of the telephone and pulled back her hand. Calls at this time of the morning only ever meant bad news. Not mum and Dad, she begged some unseen deity. Or my sisters, Please.

But the voice at the other end of the phone was not a family one. 'Mrs Macauley?'

'Yes?'

Mac was waking. She watched him unwind himself from the sofa.

'It's Mrs Carter here from the stables. I'm sorry to ring so early, but we've got a problem. Your horse appears to have escaped.'

'How the hell did it get out?' Mac sat, rubbing at his eyes. He was wearing an old T-shirt she recognised, worn soft over the years.

'She said they sometimes work out how to shift the bolts. Something to do with banging into the door and making it jump. I wasn't really listening.'

Oh, God, she was thinking. What are we going to tell Sarah? She's going to be hysterical. And she'll blame us for forcing her to bring him here.

'What do we do?'

'Mrs Carter's husband is out on a quad bike, scouring the local fields. She's going out in her four-by-four. She asked if we could grab a head-collar and get the car out. She's afraid he might make it up towards the dual-carriageway. He could have been out all night.'

Natasa hugged herself, shivering. 'Mac, we're going to have to wake her and tell her.'

Mac rubbed his face. His expression told her he was dreading that course of action as much as she was. 'Don't,' he said, pulling on a sweater. 'Let's try and find him first. No point panicking her if he's only in one of the nearby fields. She was so exhausted last night that hopefully we can find him before she wakes up.'

There was a light frost on the ground, and as they drove up the lane, the tyres crunched on the silvered tarmac. They went slowly, with the windows open, straining for sight or sound of a large brown horse. Every moving shadow in a distant copse, every mark on the icy ground suggested some recent presence. Natasha tried to form a mental map of the surrounding lanes, tried to second-guess the intentions of an animal she had never so much as petted.

'This is hopeless,' Mac said, not for the first time. 'You can hardly see over the hedges, and the noise of the engine's going to disguise anything we might hear. Let's get out.'

They parked the car at the top of the village. There was a place just by the church, Natasha remembered, where they'd be able to see most of the valley. Conor's binoculars remained in her pocket; she wasn't sure that she could distinguish Sarah's big brown horse from any other that might be in a field.

It was light now, but the air was still chilled from the night and she was cold. She had grabbed a coat but the T-shirt she wore underneath was no protection against the near zero temperature.

Mac was standing on a vault, staring across the graveyard, squinting against the low sun. As she gave him the binoculars, he caught her hugging herself. 'You okay?'

'Bit cold. I guess we came out in a hurry.' What if Sarah's woken? she thought suddenly. What if she's already discovered he's gone?

'Here.' He took off his scarf and handed it down to her.

'But then you'll be cold.'

'I don't feel it. You know that.'

She took it and put it on. It still carried the warmth of his skin, was so suffused with the scent of him that she felt briefly giddy and covered it up by walking away from him towards a stile. She knew his scent so well, the faint citrus herbiness. His clean maleness. What kind of masochism was this? She whipped the scarf off again and, sure he wasn't watching, stuffed it into her pocket, pulling her collar up.

'I can't see him,' Mac said, lowering the binoculars. 'This is hopeless. He could be anywhere. He could be behind a tall hedge. In a forest. He could be halfway to London - we simply don't know how long he's been gone.'

'It's our fault, isn't it?' Natasha folded her arms across herself.

'We were just trying to help.'

'Yup. We've really managed that so far.' She kicked at the ground, watching the crystals of frost disappear on her shoes.

He stepped down nimbly, laid a hand on her upper arm. 'Don't beat yo

urself up. We're just trying to do what's best.'

They glanced at each other, his words echoing around them.

'We should go back.' He walked past her towards the car. 'Perhaps Mrs Carter has already found him.'

She suspected neither of them believed it. Something told her that where Sarah was concerned there were no uncomplicated happy endings.

They made the short drive back in silence. If Mac noticed she was no longer wearing his scarf he said nothing. The house was still, shrouded in darkness, and they let themselves in quietly, glad of its warmth.

'I'll put the kettle on.' Natasha peeled off her coat and stood next to the range, resting her pink fingers on its hot surface.

'What are we going to tell her?'

'The truth. I mean, hell, Mac, perhaps she left the bolt undone. It may even be her fault.'

'She seemed pretty rigorous to me. Oh, Christ.' He ran a hand over his unshaven chin. 'This is going to be messy.'

Natasha pulled out two mugs and began to make coffee, dimly aware through the doorway of Mac pacing the room. He was at the windows, pulling the curtains back, and she was vaguely aware of the room flooding with grey light, illuminating the evening detritus, vinegared wine glasses and a grate full of ash.

Coffee, she thought. Then she would ring Mrs Carter. And wake Sarah.

'Tash.'

Her jaw tightened reflexively. When was he going to stop calling her that?

'Tash.'

'What?'

'You'd better come over here.'

'Why?'

'Look out of the window. The side one.'

She padded over to him, handed him a mug and peered out at her garden. Before her, what had once been a neat, rectangular lawn was now a morass of mud and churned turf. The Chinese lanterns had disappeared and the stems of the last foolhardy blooms had been broken, trodden into the damp earth. Towards the boundary with the open field, her carefully erected willow fencing had been felled and now lay in a broken heap against the apple tree. Her pots were smashed on the patio flagstones. It was a battleground, a crime scene. It was as if her beautiful, carefully tended garden had been bulldozed.

Natasha tried to take in the extent of the devastation, her breath stalling, as her disbelieving gaze moved closer to the misted window.

Just visible to the left of the patio, a short distance away on a garden bench, lay Sarah's sleeping form. She was wrapped in her winter coat and covered with the muddied remains of what had once been Natasha's best winter duvet.

A few feet away from her trailing hand, oversized in the little garden, determinedly seeking out the few remaining apples that hung from the bare branches, small clouds of steam emanating gently from his nostrils, stood a large brown horse.

Thirteen

'To turn a horse you must first look in the direction you want to go.'

Xenophon, On Horsemanship

Sarah sat on the top deck of the bus and counted out the money in her pocket for the fourth time. Enough for two weeks' rent, five bales of hay and one bag of feed; enough to fill her lock-up for another fortnight. Not nearly enough to stave off Maltese Sal. It was a quarter past three. He rarely got to the yard before four thirty. She would leave what she had with Cowboy John, or under the office door with a note, and with luck she would be gone before she had to have another conversation with him about it. Both times since she had returned Sal had mentioned the arrears. Both times she had promised to find the money, with no clear idea of how she would do it.

She was just relieved to be back. Boo had been returned to Sparepenny Lane less than a week after he had been taken away. Mac and Natasha hadn't had much choice about it: the woman at the stables had gone mad, saying she'd spent two hours driving around in the dark looking for him, accusing Sarah of being irresponsible and idiotic and saying didn't she know there were yew bushes and privet and half a dozen other things that could have poisoned him in that garden? Even Mac hadn't stuck up for her. He and Natasha had acted like she was some kind of criminal, just for mucking up a bit of grass. And she hadn't seen Mac grim before. Not angry, exactly, just that disappointed look people gave you before they let out a deep sigh.

He had worn that disappointed look as he walked her and Boo back to the stables. His hands shoved deep in his pockets, he had told her that Natasha's little garden had been precious to her, that just because Natasha didn't show much emotion it didn't mean she didn't feel it. Everyone had something they were passionate about, that they would wish to protect; surely she should know that better than most.

She had felt bad when she saw Natasha crying in the hallway. She hadn't realised how clumsy Boo would be in the garden, only that it was a place where he could be safely enclosed. Close to her. Mac didn't say much more, but the gaps in what he did say made her uncomfortable. He ended by suggesting that perhaps it would be wise if she and Natasha gave each other some space.

Nobody allowed her to say what she wanted: that they couldn't blame her for everything. She had told them both, loads of times, that she couldn't be separated from Boo. They had to understand she couldn't have left him in a strange place, calling across the black fields for what he knew. The real joke was, she had stayed so close to the house so they wouldn't worry about her.

The bad atmosphere had lingered for a few days after they had returned to London. She could tell that Natasha was still wound up about it. Sometimes she heard her and Mac talking in low voices, closing the doors quietly when they started as if she couldn't tell they were talking about her. Mac would always come out afterwards and be all forced and jolly when he saw her, calling her 'Circus Girl', like Cowboy John, and making out like it was all okay. She had been afraid, for a bit, that they would tell her to leave. But things settled back into a routine of sorts. She got up early now and did stables before school. For a few days Mac had even been up in time to give her a lift. Those mornings he had taken pictures of the yard, of Boo and Cowboy John, but then he'd got a load of teaching work and didn't come at all.

The previous evening he had called her into the kitchen (Natasha was at work; she was pretty much always at work) and handed her an envelope. 'John told me how much you need,' he had said, handing it over. 'We'll pay for Boo's keep for now, but you have to do the work. And if we find you've missed any school, or not been where you should be, we'll send him somewhere else. Is that a fair deal?'

She had nodded, feeling the notes through the thin white envelope. It was all she could do not to snatch it. When she looked up, he was watching her. 'So . . . do you think this might stop . . . some of the loose change in the house going missing?'

She had blushed then. 'I guess so,' she mumbled.

She couldn't tell him about the money she owed Sal, not while they were both still pissed off with her. Not while Mac had virtually accused her of stealing.

She tried to look on the bright side. They weren't so bad. Her horse was with her. Life was as it should be. Or as close as it could get to it, without Papa being home. And yet sometimes, while she sat on the bus in the morning, she remembered how Boo had looked in that soft sand arena, how he had seemed like he was almost floating, his pleasure at being somewhere where he had the chance to be as good as he could be. She remembered her horse, far from the smoke and the noise and the rumbling trains, galloping round and round the soft green paddock, his fine head raised, as if he were drinking in the far, far horizons, his tail held high like a banner.

'So, how's it going?'

Ruth Taylor accepted the mug of tea, leaning back a little in the plush beige sofa. It was not the kind of living room she tended to see in her everyday work, she thought, noting the artwork on the walls, the burnished expanse of antique oak floorboards. And it was nice to get a cup of tea and not have to worry about where the mug had been.

'Everything all right?' She pulled Sarah Lachapelle's file from her bag, seeing wistfully that she had four more visits that afternoon. No plush beige sofas in that lot. Two check-ups on young asylum-seekers in a grotty B

and B on Fernley Road, a boy who swore his stepdad was beating him up and a crack-addicted teenage mother in Sandown.

The couple looked at each other. A definite unspoken something passed between them before the man spoke. 'Fine,' he said. 'All fine.'

'She's settled in okay? It's been - what - four weeks now?'

'Four weeks three days,' said the woman. Mrs Macauley had arrived just after Ruth and was now perched on her chair, her briefcase by her feet, checking her watch surreptitiously as if she was waiting for permission to rush off again.

'And school? Any problems with attendance?'

Another exchange of a glance. 'We had a few problems at the start,' Mr Macauley said, 'but I think we've ironed them out. We seem to have . . . reached an understanding.'

'You've given her some boundaries, as we suggested.'

'Yes,' he said. 'I think we all understand each other a little better.'

Oh, but he was cute. Just her type, all messed-up hair and twinkly eyes. Mustn't, Ruth scolded herself. Mustn't think like that about clients. Especially not those whose wives were sitting next to them.

'She's in good health,' he continued. 'Eats well. Does her homework. She has . . . her own interests.' He turned to his wife. 'Don't know what else to say, really.'

'Sarah's doing fine,' she said crisply.

'Don't worry. I'm not here to judge you, or mark you on your parenting skills.' She smiled at them. 'This is an informal placement - kinship care, as we call it - so we don't get too involved. I've already spoken to Sarah, who says she's happy here. But I just thought that, given her recent history, it would be a good idea for me to stop by to check how it was going.'

'Like I said,' said Mr Macauley, 'it's fine, really. We've not heard from the school that there are any problems. She doesn't keep us awake with loud music. Only six or seven boyfriends. Not too many class-A drugs. Joke,' he added, as his wife glared at him.

Ruth glanced down at her file. 'Do we have an update on her grandfather? I'm sorry, I know I should have rung myself, but we've been a bit up against it in the department.'

'He's improving slowly,' Mr Macauley said, 'although I can't say I'm an expert on these things.'