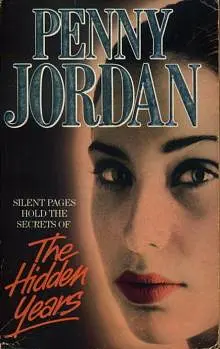

by Penny Jordan

'Maybe some of the other rooms are better,' Lizzie suggested brightly. 'Let's go and have a look, shall we?'

Half an hour later she and Edward stared at one another in silence. The house plainly had not been lived in for years. Everywhere there were signs of decay, of damp and mould… in every room. None of the rooms was really habitable, and even if they had been clean and sound there was still the small matter of the lack of furniture. Lizzie fought down a wild desire to laugh, remembering the antiques, the exquisite china, the silks and damasks she had visualised. These rooms, with their clothing of cobwebs and moulds, their once expensive wallpapers peeling from the walls, their broken windows covered in cheap blackout fabric, their panelling torn from walls, their ceilings crumbling away…these rooms were nothing like that. There was no furniture other than a collection of trestle tables and battered chairs, which had plainly been intended for the use of the men who might have been stationed here when the house was first requisitioned.

Only the kitchen bore some resemblance to the house she had visualised. It had, as she had suspected, a huge old-fashioned range, a worn deal table, two rockers either side of the range, and a large dresser with its complement of dirty pottery and copper. In one corner stood a deep sink with one tap. She turned it on experimentally, grimacing at the dirt, and watching cautiously as water started to spurt into the sink, testing it carefully with her finger and then sucking it. The water tasted clear and sharp and was icy cold, suggesting that it came from an underground spring.

As she stared around the room, although she didn't know it, Lizzie was judging it by the standards given to her by her aunt. She had already seen that the range, if it worked, must heat the domestic water, that its ovens could be used for cooking and baking and that its warmth, with its door opened, might just, just be enough to warm this large, cavernous room.

Somewhere outside in the jumble of outbuildings surrounding the yard must be a fuel store… If there was any fuel. She heard a sound and turned her head. Edward was slumped in his chair, his head in his hands. The sound she could hear, the noise tearing into the silence of the house, was the sound of his grief, she recognised dispassionately. Edward, as she had already done, was crying for his lost love, for the love which had sustained him for so long and which he was now seeing cruelly revealed in all its stark reality.

It was impossible for them to stay here, and yet it was impossible for them to go, for her to push the chair back to the station, for them to wait for another train to take them—where? To Bath? To do what?

Although Edward now owned Cottingdean, there was very little money. He had already explained that to her. The flock, which had once produced Cottingdean's wealth, had suffered through sickness during the last years of his grandparents' lives, and there had not been the money to replace the sheep.

And there had been the war; bad investments by his grandfather had further impoverished the estate. The only money Edward had came from his pension and a small trust fund. 'My God, what have I done to you?' she heard him saying harshly behind her. 'Kit must have known about this. Damn him!' A protest came to her lips, but she swallowed it. Now was not the time to champion her love. Edward was like a man who suddenly discovered that his lover had been false to him. He was beyond logic, beyond reason, beyond accepting that the extent of the decay meant that the house had fallen into disrepair long before Kit could have inherited it…

'We can't stay here…'

'I think we'll have to,' Lizzie told him gently. 'For tonight at least. If I can find some fuel I could light the range. There might be mattresses upstairs. If they were going to use the house to quarter men here, it is possible. We… I could bring two down. If we aired them in front of the range…'

'Sleep here?' Edward stared at her as though she had taken leave of her senses. 'We can't… It's impossible.'

Suddenly she could feel herself losing her temper, losing her self-control. 'We don't have any option,' she told him fiercely. 'Edward, don't you understand? I can't push you back to the village. Who knows when we would get a train, and then where would we go? To Bath? To do what? You said yourself there was no money… You said we'd have to learn to be as self-sufficient as we could; grow our own food, maintain a smallholding on the land…' When he'd said those things she'd envisaged a life filled with the kind of food served by her aunt. Milk from a Jersey cow…fresh green vegetables…soft fruits in season…eggs from their own hens. Remembering the overgrown wilderness lying either side of the drive, she knew bitterly that it would be a long, long time before such a garden could be tamed to yield any kind of food crop.

'But I didn't know it was going to be like this,' Edward whispered. He looked tired and broken, more of a child than a man. A very, very old child, who suddenly looked frighteningly frail.

To keep her mind off her own desolation, Lizzie forced herself to sound cheerful. 'Look, you wait here… I'll go outside and see if there's any fuel. If we can get the range lit…'

'We!' Edward laughed bitterly. 'We!' But Lizzie wasn't listening. She was unbolting the back door and stepping outside into the yard.

The outbuildings were in much the same state of decay as the rest of the house. She had little hope of finding any fuel. She suspected now that the panelling had been used at some stage to feed a fire, which must suggest that there was no supply of wood. Even so, she searched methodically through several small, dark sheds, before coming to the stable proper, empty now of its occupants, although it still retained a rich earthy smell of hay, manure and leather. A large tarpaulin covered something in one corner, and it was curiosity more than anything else that made her lift it. To discover beneath it an enormous pile of neatly cut and split logs was like discovering gold. At first she could hardly believe she wasn't just seeing things. She stood and blinked and then blinked again, and when the logs refused to go away she looked round quickly for something to put them in, in the end using a large galvanised bucket.

When she staggered into the kitchen with them Edward barely looked around. His skin looked grey and pinched, and he was rubbing his hands together in a way he had whenever something troubled him deeply. She had seen other patients at the hospital doing the same thing, and knew that it was not a good sign. She spoke to Edward, trying to sound positive and cheerful, but when he looked at her it was as though he no longer saw her.

When she asked him for his matches he stared blankly at her, and in the end she had to remove them gently from his pocket. She had no paper with which to light the fire and had seen no axe with which she could split up some of the logs for sticks, but there was the blackout fabric yawning from the kitchen window. She could use that, she decided ruthlessly.

As she opened the door to the range and then discovered that whoever had last lit a fire in it had not bothered to remove the ash, she reflected that at least that was one fear removed. She had dreaded discovering that the chimney was blocked off and that no fire could be lit.

She had to stand in the sink to reach up to rip down the blackout fabric. She saw Edward frowning bewilderedly at her as she did so. She gave him a reassuring smile, but said nothing. The best thing for him now was time… time and peace and quiet for him to come to terms with the reality of Cottingdean.

Strangely, now that she was actually doing something she felt much better, far less helpless and afraid. It was as though the mere activity, the simple task of lighting the range had somehow restored to her the right to control her own life. As she waited for the blessedly dry logs to catch she realised wonderingly that for the first time in her life she actually was her own mistress, that there was no aunt, no matron, no one other than Edward to direct her life. And poor Edward. How could he do that when it was so desperately obvious that he was going to be the one to lean on her?

How she knew this she had no real knowledge. It was something that might have been growing on her slowly, something that she might have subconsciously perceived without being aware of doing so. All she knew was that here, now,

in this place, she had suddenly realised that she was going to have not one life dependent upon her, but two. And she realised something else as well—a simple truth that her parents and then her aunt had inculcated into her: nothing in life came free. Everything had a price to be paid for it. Fate had given her Kit and then had demanded Kit's life in payment. It had given her Kit's child… a bonus. It had given her Edward and marriage… respectability and a home. It had given her child a future, even if now she was forced to accept that the only home, the only future her child would have would be one that she could make for it, and that the price she must pay for the privilege of doing so would be her duty towards Edward. Her duty to cherish and protect him, her duty to turn Cottingdean back into his dream of how it had once been.

Quite how she knew all this she had no idea. It was a vague, loose chain of thoughts no more than half formed, no more than vague sensory awareness slipping through her mind like fine veils of cloud, while her hands were busy feeding the fire, checking the damp; while she was going outside watching the smoke rise; while she was talking to Edward, telling him that they would soon have the kitchen warm and that she must go upstairs to see if she could find a couple of mattresses, and to check to see if the range did, as she hoped, heat the hot water supply. If not, she had already seen the massive kettles on the dresser and the tin bath hanging up behind the scullery door.

Outwardly totally absorbed by the practicalities of their situation, inwardly she was aware of feelings so strong that she wondered if they were engendered by her pregnancy rather than by her own emotions. Her strongest awareness was one of knowing that she must seize hold of her own life, that she must take charge of it and make it into something strong enough to withstand whatever blows fate raised against it, and at the bottom of this awareness lay a peculiar conviction that somehow her ability to do so was interwoven with this house and its desolate decay; that in taking hold of the house and breathing life into it she would also be taking hold of her own life and banishing from it the desolation of losing Kit.

Was it because of her child, Kit's child? The child who would one day inherit Cottingdean? Was it for him that she felt this urge, this need to take hold of the house, to cherish and love it, to restore it to what it must once have been? Or was she simply giving in to some foolish, impossible-to-achieve daydream?

It was impossible for them to use any of the bedrooms. They had to sleep in the kitchen on mattresses she had managed to salvage, wrapped in blankets she had aired over the range. The mattresses were single ones and as she lay sleepless within the cocoon of her own blankets, while Edward slept several feet away from her, she remembered how earlier Edward had made an awkward attempt to embrace her, out of gratitude, she knew, and not desire, but the sensation of his dry lips moving against her cheek had caused such a surge of revulsion inside her that she had only just managed to conceal from him what she was feeling…

Now, curled up in her thankfully solitary bed, she relived that small incident, shuddering inwardly. Her reaction to Edward's touch only reinforced her conviction that for her sexual intimacy was a part of married life she was more than pleased to have to do without.

How lucky she had been to find Edward, she thought naively. How fortunate to marry such a kind, considerate man, who was willing not only to accept her child as his own and to provide them both with a home, but was also a man who would never be able to criticise her lack of sexual responsiveness to him in the way that Kit had.

It was not perhaps a conventional beginning to their marriage, but nevertheless she was determined to make Edward a good wife, to give him all the care and devotion he might need, to love and cherish him as her husband, even if that love could never be sexual. As she fell asleep she promised fervently that from now on she would do everything she could to show Edward how grateful she was to him for what he had done for her. Somehow between them they would find a way of making Cottingdean habitable, a true home, a home filled with warmth and love, because that was what she wanted for her child. A proper home, the kind of home she herself had never really had… not after she had gone to live with her aunt.

CHAPTER SEVEN

'Today we heard officially that Japan has surrendered and the war is over.'

Liz stared down at what she had written, knowing guiltily that since she had come to Cottingdean her life had been so full of so many obstacles, so many small and intensely immediate problems, that somehow the war had lost its prominence.

Their isolation didn't help; they had no radio, no delivery of a daily paper, and they seldom had visitors.

At first she had attributed this latter lack to herself; but those visitors they had had quickly if unknowingly reassured her.

It amazed her that people here should so readily accept her as Edward's wife, ignoring her youth and the disparity of that youth and his ill health, although she had seen the way even the vicar had uncomfortably avoided looking directly at Edward for too long. Only the doctor, Ian Holmes, a bracing Northerner in his mid-fifties, seemed prepared to acknowledge Edward's infirmities.

It was true that the locals, the villagers, still treated her with reserve, but not, she was coming to realise, because they had guessed the truth about her. No… it was simply that both she and to some extent Edward himself were strangers to them.

It was from the doctor that they learned that the couple who were supposed to have been taking care of the house had left it over twelve months ago. Edward suspected that Kit must have been aware of the situation, but it was impossible now to question his cousin about his reasons for allowing the house to fall into such a state of neglect.

It hadn't taken Liz more than twenty-four hours in the house to realise how much she was going to need all the skills her aunt had taught her. What she was slower to recognise was how much of the older woman's indomitable will had also been passed on to her. No one who had any real alternative would ever choose to live in such a place, she had acknowledged despairingly the first morning, when she woke up in Cottingdean's kitchen, her body stiff and uncomfortable from the still-damp mattress, her nose wrinkling up at the stale smell of the air.

But then what alternatives had they had? She had seen the shock and bewilderment in Edward's eyes when he too woke up, the despair and the humiliation, and in that moment she had unknowingly picked up the burden she would carry for the rest of her life…

It had been an effort to persuade Edward into a more cheerful frame of mind, to insist on pushing him down to the village so that they could buy a few supplies, find out what had happened to the Johnsons, visit the doctor and present the letter from the hospital.

It had surprised her when Edward referred to her as Liz instead of Lizzie, but after a while she had decided she rather liked it. It seemed more adult, more mature. It made her feel less of a helpless child.

Somehow or other, with some help from the doctor, who had given them the names of several local farmers who might be able to spare the odd pair of hands for half a day or so, they had managed to make a small part of the house habitable; just the kitchen, on which Liz had worked ceaselessly for a week, scrubbing and re-scrubbing its floors, walls and shelves with as much hot water as the range could provide, and the coarse yellow soap she had found in the stable, until she was satisfied that it was, if not clean enough to match her great-aunt's standards, then at least a great improvement on what it had been.

Downstairs, the cleanest and driest of the rooms had received the same treatment to turn them into temporary bedrooms, and if the uncomfortable trestle beds and thin mattresses, obviously intended for the use of whoever the house had originally been requisitioned for, were even less appealing than her bed in the hostel, then at least they were somewhere to sleep, and she was so tired at night that not even the discomfort of the lumpy mattress kept her awake. Edward was another matter. She had been disturbed at first when Ian Holmes had prescribed a sleeping potion for him, but she had to admit that after a week of proper sleep Edward did look better.

/>

If they hadn't had a sudden spell of good weather, enabling her to take Edward outside in his chair while she worked on the house, she didn't know what she would have done.

It was plain that the shock of discovering the neglect and deterioration of the place he remembered had affected Edward deeply. At first he seemed sunk into such despondency that Liz began to wonder if she was doing the right thing in staying at Cottingdean, if Edward might not recover his spirits better if he wasn't confronted by the reality of the house's downfall. But where else could they go?

They were at Cottingdean almost a month before she had enough free time to explore further afield than the immediate garden.

It was the discovery of an old estate map in one of the cupboards that sparked off her decision to see more of the estate. She showed the map to Edward, suggesting that they might hang it above the fireplace in the room which he referred to as the library, but when she saw the look of pain darken his eyes she knew she had said the wrong thing. Inwardly she cursed herself for her insensitivity.

The library had been the room Edward had described to her in the most glowing terms of all. In his memories, it was a mellow, warm room, full of firelight, the scent of leatherbound books, and tobacco. Rich velvet curtains had hung at the window, and his grandfather's desk had been a huge island of polished wood. Two huge chairs had stood either side of the fire. There had been a fender high enough for someone sitting in those chairs to rest their feet on. His grandmother had always had a bowl of fresh flowers standing on his grandfather's desk, and to be allowed into the room had obviously been regarded by Edward as an extra-special treat.

Now, no one walking into it would recognise it from Edward's description. None of the furnishings he had described so lovingly to her remained; even the bookshelves themselves had been ripped out in places— whether by accident or design, Liz didn't know. Their contents, those books whose smell Edward remembered so clearly, lay in scattered disorder on the floor, their spines broken, their pages mildewed and chewed into nests by the colony of mice who had seemed to make this room their favourite domain.