by Jojo Moyes

She checks them, then takes them into the kitchen. She lights a candle, and holds the pieces, one at a time, over the flickering flame, until there is nothing left but ashes.

'There, Sophie,' she says. 'If nothing else, you can have that one on me.'

And now, she thinks, for David.

33

'I thought you'd be headed off by now. Jake's asleep in front of America's Funniest Home Videos.' Greg walks into the kitchen bare-foot and yawning. 'You want me to put up the camp bed? It's kind of late to be dragging him home.'

'That would be great.' Paul barely looks up from his files. His laptop is propped open in front of him.

'What are you doing going over those again? The verdict is due Monday, surely? And - um - didn't you just quit your job?'

'There's something I've missed. I know it.' Paul runs his finger down the page, flicking impatiently to the next. 'I have to check through the evidence.'

'Paul.' Greg pulls up a chair. 'Paul,' he says, a little louder

'What?'

'It's done, bro. And it's okay. She's forgiven you. You've made your big gesture. I think you should just leave it now.'

Paul leans back, drags his hands over his eyes. 'You think so?'

'Seriously? You look kind of manic.'

Paul takes a swig of his coffee. It is cold. 'It will destroy us.'

'What?'

'Liv loved that painting, Greg. And it will eat away at her, the fact that I'm ... responsible for taking it from her. Maybe not now, maybe not even in a year or two. But it will happen.'

Greg leans back against the kitchen unit. 'She could say the same about your job.'

'I'm okay about the job. It was time I got out of that place.'

'And Liv said she was okay with the painting.'

'Yeah. But she's backed into a corner.' When Greg shakes his head in frustration, he leans forward over his files. 'I know how things can change, Greg, how the things you swear won't bother you at the start can eat away at the good stuff.'

'But -'

'And I know how losing the things you love can haunt people. I don't want Liv to look at me one day and be fighting the thought: You're the guy who ruined my life.'

Greg pads across the kitchen and puts the kettle on. He makes three cups of coffee, and hands one to Paul. He puts his hand on his brother's shoulder as he prepares to take the other two through to the living room. 'I know you like to fix stuff, big brother of mine. But honestly? In this case you're just going to have to hope to God it all works out.'

Paul doesn't hear him. 'List of owners,' he is muttering to himself. 'List of current owners of Lefevre's work.'

Eight hours later Greg wakes to find a small boy's face looming over him. 'I'm hungry,' it says, and rubs its nose vigorously. 'You said you had Coco Pops but I can't find them.'

'Bottom cupboard,' he says groggily. There is no light between the curtains, he notes distantly.

'And you don't have any milk.'

'What's the time?'

'Quarter to seven.'

'Ugh.' Greg burrows down under the duvet. 'Even the dogs don't get up this early. Ask your dad to do it.'

'He's not here.'

Greg's eyes open slowly, fix on the curtains. 'What do you mean he's not here?'

'He's gone. The sleeping-bag's still rolled up so I don't think he slept on the sofa. Can we get croissants from that place down the road? The chocolate ones?'

'I'm getting up. I'm getting up. I'm up.' He hauls himself into an upright position, rubs his head.

'And Pirate has weed on the floor.'

'Oh. Good. Saturday's off to a flying start.'

Paul is indeed not there but he has left a note on the kitchen table: it is scribbled on the back of a list of court evidence, and placed on top of a scattered pile of papers.

Had to go. Pls can you hang on to Jake. Will call.

'Is everything okay?' Jake says, studying his face.

The mug on the table is ringed with black coffee. The remaining papers look as if they have suffered a small explosion.

'It's all fine, Small Fry,' Greg says, ruffling his hair. He folds the note, puts it into his pocket, and begins dragging the files and papers into some sort of order. 'I tell you what, I vote we make pancakes for breakfast. What do you say we pull our coats on over these pyjamas and head down to the corner shop for some eggs?'

When Jake leaves the room, he grabs his mobile phone and stabs out a text.

If you are over there getting laid right this minute,

you owe me BIG TIME.

He waits a few minutes before stuffing it into his pocket, but there is no reply.

Saturday is, thankfully, busy. Liv waits in for the buyers to come and measure up, then for their builders and architect to examine the apparently endless work that needs doing. She moves around these strangers in her home, trying to strike the right balance between accommodating and friendly, as befits the seller of the house, and not reflecting her true feelings, which would involve shouting, 'GO AWAY,' and making childish hand gestures at them. She distracts herself by packing and cleaning, deploys the consolations of small domestic tasks. She throws out two bin-bags of old clothes. She rings several rental agents, and when she tells them the amount she can afford there is a lengthy, scornful silence.

'Haven't I seen you somewhere before?' says the architect, as she places the phone back in its cradle.

'No,' she says hurriedly. 'I don't think so.'

Paul does not call.

That afternoon she heads over to her father's. 'Caroline has thrown you the most spectacular pot for Christmas,' he announces. 'You're going to love it.'

'Oh, good,' she says.

They eat salad and a Mexican dish for lunch. Caroline hums to herself while eating. Liv's father is up for a car-insurance advert. 'Apparently I have to imitate a chicken. A chicken with a no-claims bonus.'

She tries to focus on what he is saying, but she keeps thinking about Paul, replaying the previous day in her head. She is secretly surprised that he hasn't rung. Oh, God. I'm turning into one of those clingy girlfriends. And we've not even been officially together for twenty-four hours. She has to laugh at 'officially'.

Reluctant to go back to the Glass House, she stays at her father's for much longer than usual. He seems delighted, drinks too much, pulls out black-and-white pictures of her that he found while sorting through a drawer. There is something oddly grounding about going through them: the reminder that there was a whole life before this case, before Sophie Lefevre and a house she cannot afford and an awful, final day looming in court.

'Such a beautiful child.'

The open, smiling face in the picture makes her want to cry. Her father puts his arm around her. 'Don't be too upset on Monday. I know it's been tough. But we're terribly proud of you, you know.'

'For what?' she says, blowing her nose. 'I failed, Dad. Most people think I shouldn't have even tried.'

Her father pulls her to him. He smells of red wine and a part of her life that seems a million years ago. 'Just for carrying on, really. Sometimes, my darling girl, that's heroic in itself.'

It's almost four thirty when she calls him. It's been almost twenty-four hours, she rationalizes. And surely the normal rules for dating don't apply if someone has just given up half their life for you. Her heart quickens a little as she dials: she's already anticipating the sound of his voice. She pictures them, later that evening, curled up on his sofa in the crowded little flat, maybe playing cards with Jake on the rug. But the answer-phone cuts in after three rings. Liv hangs up quickly, oddly unsettled, then curses herself for being childish.

She goes for a run, showers, makes tea for Fran ('The last one only had two sugars'), sits by the phone and finally dials his number again at six thirty. Again it goes straight to the answer-phone. She doesn't have a landline number for his flat. Should she just go there? He could be at Greg's. But, she realizes, she doesn't have a number for Greg's either. She had been so disoriented

by Friday's events when they had arrived there that she's not even sure of the exact address.

This is ridiculous, she tells herself. He'll call.

He doesn't.

At eight thirty, knowing she can't face spending the rest of the evening in the house, she gets up, pulls on her coat and grabs her keys.

It's a short walk to Greg's bar, even shorter if you half run in your trainers. She pushes open the door and is hit by a wall of noise. On the small stage to the left a man dressed as a woman is singing raucously to a disco beat, accompanied by loud catcalls from a rapt crowd. At the other end, the tables are packed, the spaces between them thick with taut, tightly clad bodies.

It takes her a few minutes to spot him, moving swiftly along the bar, a tea-towel slung over his shoulder. She squeezes through to the front, half wedged under somebody's armpit, and shouts his name.

It takes several goes for him to hear her. Then he turns. Her smile freezes: his expression is oddly unwelcoming.

'Well, this is a fine time to turn up.'

She blinks. 'I'm sorry?'

'Nearly nine o'clock? Are you guys kidding me?'

'I don't know what you're talking about.'

'I've had him all day. Andy was meant to go out tonight. Instead he's had to cancel just to stay home and babysit. I can tell you he's not happy.'

Liv struggles to hear him over the noise in the bar. Greg holds up a hand, and leans forward to take someone's order.

'I mean, you know we love him, right?' he says, when he returns. 'We love him to death. But treating us like some kind of default babysitter is -'

'I'm looking for Paul,' she says.

'He's not with you?'

'No. And he's not answering his phone.'

'I know he's not answering his phone. I thought that was because he was with - Oh, this is crazy. Come through the bar.' He lifts the hatch so that she can squeeze in, holds his hands up to the roar of complaint from those waiting. 'Two minutes, guys. Two minutes.'

In the tiny corridor to the kitchen, the beat thumps through the walls, making Liv's feet vibrate. 'But where has he gone?' she says.

'I don't know.' Greg's anger has evaporated. 'We woke up to a note this morning saying he'd had to go. That was it. He was kind of weird last night after you left.'

'What do you mean, weird?'

He looks shifty, as if he's already said too much.

'What?'

'Not himself. He takes this stuff pretty seriously.' He bites his lip.

'What?'

Greg looks awkward. 'Well, he - he said he thought this painting was going to ruin any chance the two of you had of having a relationship.'

Liv stares at him. 'You think he's ...'

'I'm sure he didn't mean -'

But Liv is already pushing her way out through the bar.

Empty of anything, Sunday lasts for ever. Liv sits in her still house, her phone silent, her thoughts spinning and humming, and waits for the end of the world.

She rings his mobile number one more time, then ends the call abruptly when the answer-phone kicks in.

He's gone cold.

Of course he hasn't.

He's had time to think about everything he's throwing away by siding with me.

You have to trust him.

She wishes Mo were there.

The night creeps in, the skies thickening, smothering the city in a dense fog. She fails to watch television, sleeps in weird, disjointed snatches, and wakes at four with her thoughts congealing in a toxic tangle. At half past five she gives up, runs a bath and lies in it for some time, staring up through the skylight at the oblivious dark. She blow-dries her hair carefully, and puts on a grey blouse and pinstriped skirt that David had once said he loved on her. They made her look like a secretary, he'd observed, as if that might be a good thing. She adds some fake pearls and her wedding ring. She does her makeup carefully. She is grateful for the means to conceal the shadows under her eyes, her sallow, exhausted skin.

He will come, she tells herself. You have to have faith in something.

Around her, the world wakes up slowly. The Glass House is shrouded in mist, emphasizing her sense of isolation from the rest of the city. Beneath it, queues of traffic, visible only as tiny illuminated dots of red brake lights, move slowly, like blood in clogged arteries. She drinks some coffee, and eats half a piece of toast. The radio tells of traffic jams in Hammersmith, and a plot to poison a politician in Ukraine. When she has finished, she tidies and wipes the kitchen so that it gleams.

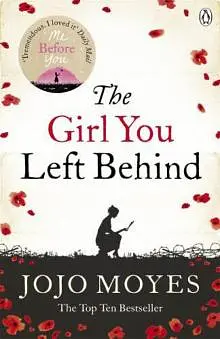

Then she pulls an old blanket from the airing cupboard and wraps it carefully around The Girl You Left Behind. She folds it as if she were wrapping a present, keeping the picture turned away from her so that she doesn't have to see Sophie's face.

Fran is not in her box. She's sitting on an upturned bucket, gazing out across the cobbles to the river, untangling a piece of twine that is wrapped several hundred times around a huge clump of supermarket carrier bags.

She looks up as Liv approaches, with two mugs, then at the sky. It has sunk around them in thick droplets, muffling sound, ending the world at the river's edge.

'Not running?'

'Nope.'

'Not like you.'

'Nothing's like me, apparently.'

Liv hands over a coffee. Fran takes a sip, grunts with pleasure, then looks at her. 'Don't stand there like a lemon, then. Take a seat.'

Liv glances around before she realizes that Fran is pointing towards a small milk crate. She pulls it over and sits down. A pigeon walks across the cobbles towards her. Fran reaches into a crumpled paper bag and throws it a crust. It's oddly peaceful out here, hearing the Thames lap gently at the shore, the distant sounds of traffic. Liv thinks wryly of what the newspapers would say if they could see the society widow's breakfast companion. A barge emerges through the mist and floats silently past, its lights disappearing into the grey dawn.

'Your friend left, then.'

'How do you know?'

'Sit here long enough you get to know everything. You listen, see?' She taps the side of her head. 'Nobody listens any more. Everyone knows what they want to hear, but nobody actually listens.'

She stops for a minute, as if remembering something. 'I saw you in the newspaper.'

Liv blows on her coffee. 'I think the whole of London has seen me in the newspaper.'

'I've got it. In my box.' She gestures towards the doorway. 'Is that it?' She points to the bundle Liv is holding under her arm.

'Yes.' She takes a sip. 'Yes, it is.' She waits for Fran to add her own take on Liv's crime, to list the reasons why she should never have attempted to keep the painting, but it doesn't come. Instead she sniffs, looks out at the river.

'That's why I don't like having too much stuff. When I was in the shelter people was always nicking it. Didn't matter where you left it - under your bed, in your locker - they'd wait till you was going out, and then they'd just take it. It got so's you didn't want to go out, just for fear of losing your stuff. Imagine that.'

'Imagine what?'

'What you lose. Just trying to hang on to a few bits.'

Liv looks at Fran's craggy, weathered face, suddenly suffused with pleasure as she considers the life she is no longer missing out on.

'It's a kind of madness,' Fran says.

Liv stares along the grey river, and her eyes fill unexpectedly with tears.

34

Henry is waiting for her by the rear entrance. There are television cameras, as well as the protesters at the front of the High Court for the last day. He had warned her there would be. She emerges from the taxi, and when he sees what she is carrying, his smile turns into a grimace. 'Is that what I ... You didn't have to do that! If it goes against us we'd have made them send a security van. Jesus Christ, Liv! You can't just carry a multi-million-pound work of art around like a loaf of bread.'

Liv's hands are tight around it. 'Is Paul here?'

'Paul?' He's hurrying her towards the courts, like a doctor

ferrying a sick child into a hospital.

'McCafferty.'

'McCafferty? Not a clue.' He glances again at the bundle. 'Bloody hell, Liv. You could have warned me.'

She follows him through Security and into the corridor. He calls the guard over and motions to the painting. The guard looks startled, nods, and says something into his radio. Extra security is apparently on its way. Only when they actually enter the courtroom does Henry begin to relax. He sits, lets out a long breath, rubs at his face with both palms. Then he turns to Liv. 'You know, it's not over yet,' he says, smiling ruefully at the painting. 'Hardly a vote of confidence.'

She says nothing. She scans the courtroom, which is fast filling around them. Above her in the public gallery the faces peer down at her, speculative and impassive, as if she herself is on trial. She tries not to meet anyone's eye. She spies Marianne in tangerine, her plastic earrings a matching shade, and the old woman gives a little wave and an encouraging thumbs-up; a friendly face in a sea of blank stares. She sees Janey Dickinson settle into a seat further along the bench, exchanging a few words with Flaherty. The room fills with the sound of shuffling feet, polite conversation, scraping chairs and dropped bags. The reporters chat companionably to each other, swigging at polystyrene cups of coffee and sharing notes. Someone hands someone else a spare pen. She's trying to quell a rising sense of panic. It's nine forty. Her eyes stray towards the doors again and again, watching for Paul. Have faith, she thinks. He will come.

She tells herself the same thing at nine fifty, and nine fifty-two. And then at nine fifty-eight. Just before ten o'clock, the judge enters. The courtroom rises. Liv feels a sudden panic. He's not coming. After all this, he's not coming. Oh, God, I can't do this if he's not here. She forces herself to breathe deeply and closes her eyes, trying to calm herself.

Henry is paging through his files. 'You okay?'

Her mouth appears to have filled with powder. 'Henry,' she whispers, 'can I say something?'

'What?'

'Can I say something? To the court? It's important.'

'Now? The judge is about to announce his verdict.'

'This is important.'