by Jojo Moyes

They had been walking around the back of Placa de Catalunya when they heard the American woman's voice. She had been shouting at a trio of impassive men, close to tears as they emerged through a panelled doorway, dumping furniture, household objects and trinkets in front of the apartment block. 'You can't do this!' she had exclaimed.

David had released Liv's hand and stepped forwards. The woman - an angular woman in early middle age with bright blonde hair - had let out a little oh oh oh of frustration as a chair was dumped in front of the house. A small crowd of tourists had stopped to watch.

'Are you okay?' he had said, his hand at her elbow.

'It's the landlord. He's clearing out all my mother's stuff. I keep telling him I have nowhere to put these things.'

'Where is your mother?'

'She died. I came over here to sort through it all and he says it has to be out by today. These men are just dumping it on the street and I have no idea what I'm going to do with it.'

She remembers how David had taken charge, how he had told Liv to take the woman to the cafe across the road, how he had remonstrated with the men in Spanish as the American woman, whose name was Marianne Johnson, sat and drank a glass of iced water and gazed anxiously across the street. She had only flown in that morning, she confided. She swore she did not know whether she was coming or going.

'I'm so sorry. When did your mother die?'

'Oh, three months ago. I know I should have done something sooner. But it's so hard when you don't speak Spanish. And I had to get her body flown home for the funeral ... and I just got divorced so there's only me doing everything ...' She had huge white knuckles beneath which she had crammed a dizzying array of plastic rings. Her hairband was turquoise paisley. She kept reaching up to touch it, as if for reassurance.

David was talking to a man who might have been the landlord. He had appeared defensive initially, but now, ten minutes later, they were shaking hands warmly. He reappeared at their table. She should sort out which things she wanted to keep, David said, and he had a number for a shipping company that could pack those items and fly them home for her. The landlord had agreed to let them remain in the apartment until tomorrow. The rest could be taken and disposed of by the removal men for a small fee. 'Are you okay for money?' he had said quietly. The kind of man he was.

Marianne Johnson had nearly wept with gratitude. They had helped her move things, stacking objects right or left depending on what should be kept. As they had stood there, the woman pointing at things, moving them carefully to one side, Liv had looked more closely at the items on the pavement. There was a Corona typewriter, huge leather-bound albums of fading newsprint. 'Mom was a journalist,' said the woman, placing them carefully on a stone step. 'Her name was Louanne Baker. I remember her using this when I was a little girl.'

'What is that?' Liv pointed at a small brown object. Even though she was unable to make it out without stepping closer, some visceral part of her shuddered. She could see what looked like teeth.

'Oh. Those. Those are Mom's shrunken heads. She used to collect all sorts. There's a Nazi helmet somewhere too. D'you think a museum might want them?'

'You'll have fun getting them through Customs.'

'Oh, God. I might just leave it on the street and run.' She paused to wipe her forehead. 'This heat! I'm dying.'

And then Liv had seen the painting. Propped up against an easy chair, the face was somehow compelling even among the noise and the chaos. She had stooped and turned it carefully towards her. A girl looked out from within the battered gilt frame, a faint note of challenge in her eyes. A great swathe of red-gold hair fell to her shoulders; a faint smile spoke of a kind of pride, and something more intimate. Something sexual.

'She looks like you,' David had murmured, under his breath, from beside her. 'That's just how you look.' Liv's hair was blonde, not red, and short. But she had known immediately. The look they exchanged made the street fade.

David had turned to Marianne Johnson. 'Don't you want to keep this?'

She had straightened up, squinted at him. 'Oh - no. I don't think so.'

David had lowered his voice. 'Would you let me buy it from you?'

'Buy it? You can have it. It's the least I can do, given you've saved my darned life.'

But he had refused. They had stood there on the pavement, engaged in a bizarre reverse haggling, David insisting on giving her more money than she was comfortable with. Finally, as Liv continued to sort through a rail of clothes, she turned to see them shaking on a price.

'I would gladly have let you have it,' she said, as David counted out the notes. 'To tell you the truth, I never much liked that painting. When I was a kid I used to think she was mocking me. She always seemed a little snooty.'

They had left her at dusk with his mobile number, the pavement clear in front of the empty apartment, Marianne Johnson gathering her belongings to go back to her hotel. They had walked away in the thick heat, him beaming as if he had acquired some great treasure, holding the painting as reverently as he would hold Liv later that evening. 'This should be your wedding present,' he had said. 'Seeing as I never gave you anything.'

'I thought you didn't want anything interrupting the clean lines of your walls,' she had teased.

They had stopped in the busy street, and held it up to view it again. She remembers the taut, sunburned skin at the back of her neck, the fine dusty sheen on her arms. The hot Barcelona streets, the afternoon sun reflected in his eyes. 'I think we can break the rules for something we love.'

'So you and David bought that painting in good faith, yes?' says Kristen. She pauses to swat the hand of a teenager scrabbling among the contents of the fridge. 'No. No chocolate mousse. You won't eat supper.'

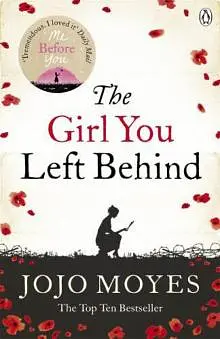

'Yes. I even managed to dig out the receipt.' She had it in her handbag: a piece of tattered paper, torn from the back of a journal. Received with thanks for portrait, poss called The Girl You Left Behind. 300 francs - Marianne Baker (Ms).

'So it's yours. You bought it, you have the receipt. Surely that's the end of it. Tasmin? Will you tell George it's supper in ten minutes?'

'You'd think. And the woman we got it from said her mother'd had it for half a century. She wasn't even going to sell it to us - she was going to give it to us. David insisted on paying her.'

'Well, the whole thing is frankly ridiculous.' Kristen stops mixing the salad and throws up her hands. 'I mean, where does it end? If you bought a house and someone stole the land in the land grabs of the Middle Ages, does that mean some day someone's going to claim your house back too? Do we have to give back my diamond ring because it might have been taken from the wrong bit of Africa? It was the First World War, for goodness' sake. Nearly a hundred years ago. The legal system is going too far.'

Liv sits back in her chair. She had called Sven that afternoon, trembling with shock, and he had told her to come over that evening. He had been reassuringly calm when she had told him about the letter, had actually shrugged as he read it. 'It's probably a new variation on the ambulance-chasing thing. It all sounds very unlikely. I'll check it out - but I wouldn't worry. You've got a receipt, you bought it legally, so I'm guessing there's no way this could stand up in a court of law.'

Kristen deposits the bowl of salad on the table. 'Who is this artist anyway? Do you like olives?'

'His name is Edouard Lefevre, apparently. But it's not signed. And yes. Thank you.'

'I meant to tell you ... after the last time we spoke.' Kristen looks up at her daughter, shepherds her towards the door. 'Go on, Tasmin. I need some mummy time.'

Liv waits as, with a disgruntled backwards look, Tasmin slopes out of the room. 'It's Rog.'

'Who?'

'I have bad news.' She winces, leans forward over the table. Takes a deep, theatrical breath. 'I wanted to tell you last week but I couldn't work out what to say. You see, he did think you were terribly nice, but I'm afraid you're not ... well ... he says you're not his type.'

'Oh?'

'He really want

s someone ... younger. I'm so sorry. I just thought you should know the truth. I couldn't bear the idea of you sitting there waiting for him to call.'

Liv is trying to straighten her face when Sven enters the room. He is holding a page of scribbled notes. 'I just got off the phone with a friend of mine at Sotheby's. So ... the bad news is that TARP is a well-respected organization. They trace works that have been stolen, but increasingly they're doing the tougher stuff, works that disappeared during wartime. They've returned some quite high-profile pieces in the last few years, some from national collections. It appears to be a growth area.'

'But The Girl isn't a high-profile work of art. She's just a little oil painting we picked up on our honeymoon.'

'Well ... that's true to an extent. Liv, did you look up this Lefevre chap after you got the letter?'

It was the first thing she had done. A minor member of the Impressionist school at the turn of the last century. There was one sepia-tinted photograph of a big man with dark brown eyes and hair that reached down to his collar. Worked briefly under Matisse.

'I'm starting to understand why his work - if it is his work - might be the subject of a restitution request.'

'Go on.' Liv pops an olive into her mouth. Kristen stands beside her, dishcloth in hand.

'I didn't tell him about the claim, obviously, and he can't value it without seeing it, but on the basis of the last sale they held for Lefevre, and its provenance, they reckon it could easily be worth between two and three million pounds.'

'What?' she says weakly.

'Yes. David's little wedding gift has turned out to be a rather good investment. Two million pounds minimum were his exact words. In fact, he recommended you get an insurance valuation done immediately. Apparently our Lefevre has become quite the man in the art market. The Russians have a thing for him and it's pushed prices sky high.'

She swallows the olive whole and begins to choke. Kristen thumps her on the back and pours her a glass of water. She sips it, hearing his words going round in her head. They don't seem to make any sense.

'So, I suppose it should actually come as no great surprise that there are people suddenly coming out of the woodwork to try to get a piece of the action. I asked Shirley at the office to dig out a few case studies and email them over - these claimants, they dig around a little in the family history, claim the painting, saying it was so precious to their grandparents, how heartbroken they were to lose it ... Then they get it back, and what do you know?'

'What do we know?' says Kristen.

'They sell it. And they're richer than their wildest dreams.'

The kitchen falls silent.

'Two to three million pounds? But - but we paid two hundred euros for her.'

'It's like Antiques Roadshow,' says Kristen, happily.

'That's David. Always did have the Midas touch.' Sven pours himself a glass of wine. 'It's a shame they knew it was in your house. I think, without a warrant or proof of any kind, they might not have been able to prove you had it. Do they know for sure it's in there?'

She thinks of Paul. And the pit of her stomach drops. 'Yes,' she says. 'They know I have it.'

'Okay. Well, either way,' he sits down beside her and puts a hand on her shoulder, 'we need to get you some serious legal representation. And fast.'

Liv sleepwalks through the next two days, her mind humming, her heart racing. She visits the dentist, buys bread and milk, delivers work to deadline, takes mugs of tea downstairs to Fran and brings them back up when Fran complains she has forgotten the sugar. She barely registers any of it. She is thinking of the way Paul had kissed her, that accidental first meeting, his unusually generous offer of help. Had he planned this from the start? Given the value of the painting, had she actually been the subject of a complicated sting? She Googles Paul McCafferty, reads testimonials about his time in the Art Squad of the NYPD, his 'brilliant criminal mind', his 'strategic thinking'. Everything she has believed about him evaporates. Her thoughts spin and collide, veer off in new, terrible directions. Twice she has felt so sick that she has had to leave the table and splash her face with cold water, resting it against the cool porcelain of the cloakroom.

Last November TARP helped return a small Cezanne to a Russian Jewish family. The value of the painting was said to be in the region of fifteen million pounds. TARP, its website states in the section About Us, works on a commission basis.

He texts her three times: Can we talk? I know this is difficult, but please - can we just discuss it? He makes himself sound so reasonable. Like someone almost trustworthy. She sleeps sporadically, and struggles to eat.

Mo watches all this and, for once, says nothing.

Liv runs. Every morning, and some evenings too. Running has taken the place of thinking, of eating, sometimes of sleeping. She runs until her shins burn and her lungs feel as if they will explode. She runs new routes: around the back-streets of Southwark, across the bridge into the gleaming outdoor corridors of the City, ducking the besuited bankers and the coffee-bearing secretaries as she goes.

She is headed out on Friday evening at six o'clock. It is a beautiful crisp evening, the kind where the whole of London looks like the backdrop to some romantic movie. Her breath is visible in the still air, and she has pulled a woollen beanie low over her head, which she will shed some time before Waterloo Bridge. In the distance the lights of the Square Mile glint across the skyline; the buses crawl along the Embankment; the streets hum. She plugs in her iPod earphones, closes the door of the block, rams her keys into the pocket of her shorts, and sets off at a pace. She lets her mind flood with the deafening thumping beat, dance music so relentless that it leaves no room for thought.

'Liv.'

He steps into her path and she stumbles, thrusting out a hand and withdrawing it, as if she's been burned, when she realizes who it is.

'Liv - we have to talk.'

He is wearing the brown jacket, his collar turned up against the cold, a folder of papers under his arm. Their eyes lock, and she whips round before she can register any kind of feeling and sets off, her heart racing.

He is behind her. She does not look round but she can just make out his voice above the volume of her music. She turns it up louder, can almost feel the vibration of his footsteps on the paving behind her.

'Liv.' His hand reaches for her arm and, almost instinctively, she launches her right hand round and whacks him, ferociously, in the face. The shock of impact is so great that they both stumble backwards, his palm pressed against his nose.

She pulls out her earphones. 'Leave me alone!' she yells, recovering her balance. 'Just piss off.'

'I want to talk to you.' Blood trickles through his fingers. He glances down and sees it. 'Jesus.' He drops his files, struggles to get his spare hand into his pocket, pulling out a large cotton handkerchief, which he presses to his nose. The other hand he holds up in a gesture of peace. 'Liv, I know you're mad at me right now but you -'

'Mad at you? Mad at you? That doesn't begin to cover what I feel about you right now. You trick your way into my home, give me some bullshit about finding my bag, smooth-talk your way into my bed, and then - oh, wow, what a surprise - there is the painting you just happen to be employed to recover for a great big fat commission.'

'What?' His voice is muffled through the handkerchief. 'What? You think I stole your bag? You think I made this thing happen? Are you crazy?'

'Stay away from me.' Her voice is shaking, her ears ringing. She is walking backwards down the road away from him. People have stopped to watch them.

He starts after her. 'No. You listen. For one minute. I am an ex-cop. I'm not in the business of stealing bags, or even, frankly, returning them. I met you and I liked you and then I discovered that, by some shitty twist of Fate, you happen to hold the painting that I'm employed to recover. If I could have given that particular job to anyone else, believe me, I would have done. I'm sorry. But you have to listen.'

He pulls the handkerchief away from his face. There

is blood on his lip.

'That painting was stolen, Liv. I've been through the paperwork a million times. It's a picture of Sophie Lefevre, the artist's wife. She was taken by the Germans, and the painting disappeared straight afterwards. It was stolen.'

'That was a hundred years ago.'

'You think that makes it right? You know what it's like to have the thing you love ripped away from you?'

'Funnily enough,' she spits, 'I do.'

'Liv - I know you're a good person. I know this has come as a shock, but if you think about it you'll do the right thing. Time doesn't make a wrong right. And your painting was stolen from the family of that poor girl. It was the last they had of her and it belongs with them. The right thing is for it to go back.' His voice is soft, almost convincing. 'When you know the truth about what happened to her I think you're going to look at Sophie Lefevre quite differently.'

'Oh, save me your sanctimonious bullshit.'

'What?'

'You think I don't know what it's worth?'

He stares at her.

'You think I didn't check out you and your company? How you operate? I know what this is about, Paul, and it's got nothing to do with your rights and wrongs.' She grimaces. 'God, you must think I'm such a pushover. The stupid girl in her empty house, still grieving for her husband, sitting up there knowing nothing about what's under her own nose. It's about money, Paul. You and whoever else is behind this wants her because she's worth a fortune. Well, it's not about money for me. I can't be bought - and neither can she. Now leave me alone.'

She spins round and runs on before he can say another word, the deafening noise of her heartbeat in her ears drowning all other sound. She only slows when she reaches the South Bank Centre and turns. He has gone, swallowed among the thousands of people crossing the London streets on their way home. By the time she makes it back to her door she is holding back tears. Her head is full of Sophie Lefevre. It was the last they had of her. The right thing is for it to go back. 'Damn you,' she repeats under her breath, as she tries to shake off his words. Damn you damn you damn you.