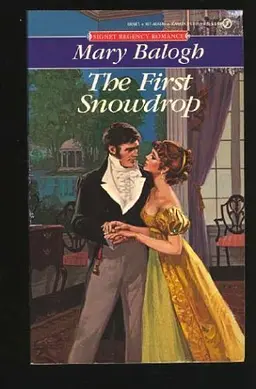

by Mary Balogh

Anne did not look up at him. She was examining the backs of her hands. "Yes," she whispered.

"I shall bid you good morning, then," Merrick said, hesitating only a brief moment before striding from the room.

Anne saw him again only as he rode away alone on the high seat of a curricle. She was standing at the window of the morning room, which she had not left since he had said his farewell.

PART 2

March and April, 1816

Chapter 5

It was a bright spring morning. The library windows were wide open to admit the crisp fresh air and the smell of daffodils and new foliage. Outside, the sun shone from a brilliant blue sky onto a new and shining world below. The woods to the west of the house were in bright-green leaf, and the grass beneath them was painted with snowdrops, primroses, and early bluebells. The formal gardens that stretched before the house had been freshly raked, clipped, and mown even though the flowers had not yet bloomed. The new marble fountain at its center spouted clear water from the mouth of a fat cherub.

Inside the library, a slim young lady sat at a delicately carved escritoire, writing paper and pens spread out before her. But she was not writing; she was reading a letter, a slight crease on her brow. She suited her surroundings admirably. A vase of daffodils stood beside her and complemented the primrose color of her light muslin day dress. Her light-brown hair was fashionably dressed, curling softly about her face, tied high at the back, with ringlets clustering against her head and neck. Her heart-shaped face rested on one slim hand as she read, a rather wistful look in her large gray eyes:

You really must come, my dear. I shall not take no for an answer. Unless every member of the family is present for our fiftieth wedding anniversary, both His Grace and I will consider the occasion quite a failure. And you are very definitely a member of the family, though we have not yet met you. It will not do at all, you know, to say that your husband will not permit you to come. I have never heard such nonsense in my life. You must learn from me, my dear, that men sometimes need quite firm handling. You must never let them think that they can control your every movement, or they will become insufferably dictatorial.

Of course, if he has expressly forbidden you to come, you are in a somewhat awkward position. Let me put the matter this way. His Grace is the head of this family. That means that his word is law to all the other members, your husband included. And His Grace has this moment declared in his most forceful ducal manner that I am to say he commands you to come. You have no choice, you see. You must obey a higher authority than your husband. And His Grace added that he will send our own best traveling carriage to bring you. You cannot possibly refuse such an offer. He is most possessive of all his conveyances. You cannot know what an honor he does you. You are to come two days before anyone else is due to arrive so that we will have an opportunity to get to know our granddaughter. It strikes me as a great absurdity that you have held that position for well over a year, yet we have still not had the pleasure of your acquaintance.

Do not fret your mind over Alex, my dear. You may leave him to His Grace and me. Sometimes he needs a severe set-down; he is too stubborn by half. He will not be able to scold you when he knows that you were ordered to come here by His Grace himself. Alex was always a little in awe of his grandfather.

The letter went on to make very definite arrangements of dates and times. Although it was only paper she held in her hand, Anne Stewart felt as if she were in the presence of a very powerful will. She had received the first invitation almost a month before to spend two weeks at Portland House with the rest of the family of the duke and duchess to celebrate their fiftieth wedding anniversary. She had not known what to do on that occasion. She had wanted to go; the letter from the duchess had sounded so friendly. She had written to her husband to ask if she might accept the invitation. His answer had been swift and bluntly in the negative.

However, it appeared now that the duchess was not prepared to accept her refusal. And she had put Anne in a very awkward position. She could not disobey her husband. Although she had not seen him since the morning after their wedding well over a year before, she had always obeyed his final command. Yet she could not disobey the Duke of Portland, either. He was the head of the family into which she had married.

She put the duchess's letter down on the escritoire and crossed to the window. It was so lovely outside. There were the spring flowers growing wild in the grass among the trees. And the daffodils were growing almost as wild beneath the window. The gardener had asked her if he should thin them out, and if he should try to cut back the wild growth at the edge of the wood, where it could be seen from the house. But she had said no to both suggestions. It was the flowers that had kept her sane the year before, she would swear until her dying day. Perhaps they did not quite fit the image of formal beauty that she had had created down the long stretch of land before the house, but that did not matter. The grounds were large enough to allow for great variety.

The formal gardens were one of her great triumphs. When she had finally pulled herself free from the dismals that had engulfed her through those long winter months after Alexander had so cruelly abandoned her, her thoughts had turned toward improving the house and the estate. And she had begun with the garden, planning eagerly with the gardener what might be done, summoning, on his advice, a well-known landscape artist from London to come and draw up plans. The fountain had been his idea, but she had chosen the design, and that cherub that looked so much like the child she would like to have had.

The improvements had taken all summer to complete, and had been costly, but they had been worth every moment and every penny, Anne reflected with a smile. The house now looked stately and quite lovely as one approached it up the curved drive lined with elm trees. And to her, alone in the house much of the time, the garden had afforded hours of pleasure. She had written her husband to ask permission to make the improvements, and he had made no objection. Even when the bills began pouring in, rather heavier than she had expected, he had made no comment, but presumably had paid them all. In fact, she had found her husband to be quite indulgent. He had never refused her anything, except once a visit to London to stay with Sonia for a week, and now a visit to his grandparents. Of course, he had always refused her his company, though she had never asked for it.

She dearly wanted to go. It would be a nerve-racking experience, of course. The duchess made it appear as if all members of the family were to be there, and the house party was to last for two weeks. Anne's shyness made her cringe at the thought of having to meet all those people and to socialize with them for many days. And the duchess seemed a formidable character, the sort of personality against which Anne's might crumble altogether. The duke sounded like a veritable tyrant. But, despite all these facts, they were all her family. They were people she had every right to know. And Anne had always felt the absence of family. Her father had never had much contact with his relatives, and her mother's had withdrawn from their life on her death. She had never felt any particular happiness in the company of either Papa or Bruce. The idea of joining a large family group and knowing that she belonged was an attractive one.

The big problem, of course, was that if the whole family was to be present for the occasion, Alexander would be one of their number. She would see him again. She would be terrified of facing him, knowing that she had disobeyed him in being there. And she had vivid, nightmare memories of that last interview she had had with him, when he had been so cold and unyielding, so devoid of all human sympathy. She recalled with a shiver the distaste and scorn for her that he had not tried to hide from his face or his voice. It had taken her a long time to recover any sort of self-esteem after that experience. He had made her feel utterly ugly and worthless. Should she willingly open herself to another such attack? Would the duchess's assurance that she would explain the situation to him save her from his wrath?

But she had to admit to herself that it was the near certainty of Alexander's presence at Portla

nd House that was really attracting her most. She had tried so hard to hate him; indeed, she did hate him. It was hard to excuse or forgive anyone who could treat a fellow human being with such contempt and cruelty. Yet she had never been able to fall out of love with him. She had relived so many times that first meeting, when he had been so charming, and their wedding night, when he had taught her physical passion and fulfillment, that she was no longer sure what was truth and what was fantasy. Was he really as handsome as she remembered? After he had been gone a few days, she had found that she could see clearly in her mind everything about him except his face. And, as time went on, his whole image blurred, so that she could no longer be sure of anything.

But much as she hated and feared her husband, Anne longed to see him again. She knew from Sonia, who had spent a week with her the summer before, that he really was handsome and charming and that many women found him attractive. She had learned about the betrothal that he had been about to make when he had married her, and the knowledge had helped explain his bitterness on that occasion. Sonia had finally revealed to her, apparently with great reluctance, that he had a mistress, a married lady of great beauty and wit. But all she knew about him from her own experience was the little she had learned during the few brief days of their acquaintance. She had not even known his given name until it was mentioned during their wedding ceremony. She had never used the name to him. There had been a few letters, all of them in answer to ones she had written, and all of them short and to the point. There was never a word of a personal nature. Even so, those letters had always been housed beneath the pillow of her bed for many nights.

Did she dare? she wondered. Did she dare defy him and go to Portland House, where they would be forced into each other's company for two whole weeks? Would he humiliate her by sending her home again immediately if she did? Would he arrive with his mistress and create for her a hopelessly embarrassing situation? But she did not think she need fear any of these things. Surely the duke would not allow her to be sent home in disgrace. And surely Alexander would not do anything as distasteful as to bring his mistress to his grandparents' home. She would surely be safe from total humiliation.

But how would she behave when confronted with him again? She had dreamed of such a meeting for so long. Was he still laboring under that ridiculous idea he had had that she had somehow lured him into marriage? Almost as if she had seen him coming along the highway and had arranged for the storm to strand him with her. And would he hate her as much if he could see her now? She knew that she was changed from what she had been when he last saw her. The weight had gone first. It had not been a deliberate loss at the start. Her clothes were hanging about her, and Mrs. Rush was clucking her concern before Anne had known that she had lost any weight at all. Misery is a fine enforcer of diets, she had discovered.

When spring had come and she had turned almost defiantly to improving the surroundings in which she seemed doomed to live for the rest of her life, she had also turned her attention to herself. She was slim but haggard, terribly dressed in clothes that would have been unappealing even if they had fit. Her hair had been allowed to grow thick and style-less. It was lifeless and dull. It was at that point that she had discovered what a gem of a maid she had in Bella. The girl had an eye for color and design, and clever hands for arranging. Equally important, perhaps, she had a cousin who was a ladies' maid in a noble house in London. From this cousin she received frequent letters, full of information about the latest styles in clothes and hairstyles.

All Bella needed was a willing victim on whom to practice these new ideas. When she realized that her mistress was becoming dissatisfied with the appearance that the girl had long deplored, she set to work. A creative and eager little seamstress from the neighboring village became a willing accomplice, and soon Anne had as fashionable a wardrobe as many a lady in town, and as stylish a hairdo as any. Bella was extremely proud of her creation and took to scolding her lady if the latter became too interested in Cook's best teatime delights, or if she became so engrossed in her garden that she allowed the wind its will on her complexion and uncovered hair.

If Anne did not quite trust the opinion of her looking glass, she had to believe the praise of Bella, who was just as willing to hand out scoldings, and of Sonia, who had enthusiastically given it as her opinion that marriage must agree with her friend, until she learned the true state of affairs. And there were those looks that she frequently intercepted at church on Sundays, looks from neighboring gentry and from the occasional visitor to the area, telling her that she was desirable or at least worthy of a second glance. She felt pretty, more so than she ever had in her life, even including the time when Dennis was alive.

Was it wise to deliberately seek out Alexander again and risk having her new confidence in herself dashed? He could do it with one sneer. On the other hand, if she could surprise only one look of appreciation or admiration from him, her image of herself would be complete.

Anne wandered back to the escritoire and looked down at the blank paper that lay there. She would accept. She might as well sit down and write to the duchess immediately. She knew deep down that however long she pondered the problem, she would end up going. How could she resist? Alexander would never come to her. That much had become obvious to her a long time before. And she would probably never have the chance again of provoking a meeting with him. It might be very unwise to do so, but the opportunity was quite irresistible. Anyway, she thought, she had the feeling that the duchess really would not accept a refusal. That carriage would come whether she said it might or not, except that if she said no, it might very well contain a very irate duke when it did arrive. He might prove to be just as frightening an adversary as Alexander.

Anne sat and began to write fast, her head bent to the task.

************************************

Alexander Stewart, Viscount Merrick, rode his favorite horse to his grandparents' home. It was a beautiful spring day, and Portland House was a mere thirty miles south of London. He left his valet to follow after with a carriage and his trunks.

He was looking forward to the two-week holiday. It was a long time since he had spent more than a single night with his grandparents. Yet to him they were like parents. They had brought him up. Their house seemed more like home to him than his own because that was where he had spent his childhood and his boyhood until he went away to school. Even then, it was to Portland House he had gone during vacations.

He had a great fondness for the two old people. The duke sometimes fooled people who did not know him into thinking that he was some kind of ogre. He certainly looked the part: extremely tall and stout, with florid complexion and steely gray eyes. His coughs and wheezes could easily be mistaken for bellows of rage. And the duchess abetted this image by constantly referring to her husband's commands and pronouncements, as if only she stood between the listener and his wrath. But Merrick knew by experience that a milder man than his grandfather did not exist, but that it was his grandmother who ruled the household and the family with an iron hand. Yet hers was a benevolent rule. Though tyrannical by nature, she had the interests of her family at heart.

It was this fact that had caused Merrick to keep her at arms' length during the last while. She did not approve of the direction his life had taken and she made no scruples about saying so. She had, as he expected, been loudly horrified by the news of his precipitate marriage, and quite irate at his weakness in giving in to the persuasions of a mere country gentleman. She was even more enraged to learn- there had been no keeping it from her-that before abandoning his bride, her grandson had been foolish enough to consummate the marriage. She had refused to talk to him any more during that visit he had made a few days after his wedding.

Yet only a week or so later, the duchess had appeared at his London residence, the duke in tow, demanding to know where his wife was, how long he planned to keep her incarcerated in the country, and when he planned to present her to them. It had been very difficult to re

main firm against her persuasions. She had argued that since his marriage was an accomplished fact, he must make the best of it. The girl must be presented to society; she must be given a chance to acquire some town bronze. She must begin producing his heirs.

But Merrick had stood firm and the duchess had finally gone home, beaten for one of the few times in her life. At least, he had assumed that she had accepted defeat. But it seemed not. He had been completely surprised to receive a letter from his wife a few weeks previously to ask if she might accept an invitation to the house party that was being held in honor of the fiftieth wedding anniversary of his grandparents. Sly old Grandmamma! He had had to write back to refuse his permission, feeling himself the tyrant, as usual.

Merrick frowned and pulled his horse out into the middle of the road, so that he might pass a farmer's wagon loaded with hay, which swung precariously from side to side in front of him. Why did he have to think of Anne and spoil the lighthearted mood that the day and his destination had brought on him? The trouble was that she so often ruined his mood. He just could not put her out of his mind, and the more time passed, the more he thought of her.

It was terrible enough to know that one had done wrong, but it was even worse to know that one had been too lazy or too cowardly or too something to do anything to put the situation right again. The trouble with guilt was that it had the tendency to fester and grow. And the longer one put off the moment of restitution, the harder it became to do anything. He had known soon after leaving his wife at Red-lands, perhaps even before leaving, that his suspicions and accusations were unjust. He had gone over almost word for word their first meeting and had admitted that she had made no deliberate attempt to deceive him into thinking that she was a servant.