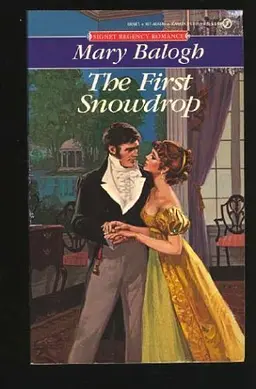

by Mary Balogh

Yet somehow it is not so easy to resist when one is faced by the righteous and tight-lipped owner of a house with which one has made free for a night and a morning. Especially when that owner is accompanied by a very sober and stern-looking country vicar who stares at one as if he can see a devil and its pitchfork over one's shoulder. And more especially when one knows oneself not entirely blameless. It still seemed miraculous to Merrick that he had not bedded the girl when he had so obviously overcome any resistance that she might have offered.

Almost in a dream, he had agreed that the honorable thing to do was to offer for the girl. Before the idea had had a chance to take root in his mind, before he had had time to realize that he would lose Lorraine and all his dreams for the future, Merrick found himself in the library awaiting the arrival of the girl. Even then he had not realized the finality of the situation. Surely she would laugh at the notion of marrying a complete stranger and moving away with him. She would refuse him. Gallantry dictated that he treat her with courtesy. He had found when confronted with her that he could not be wholly truthful and explain that he was offering only because her brother and the vicar considered it the honorable course for him to take. He had had to pretend that he really wished the match.

But surely she should have realized the truth. She must know that in real life men did not that easily make a decision to marry a strange girl. She must know that she was a dowd whom no man in his right mind could fall for within the course of a few hours. He expected her to reject him, had not dared to think of what he would be facing if she accepted. His mind had become completely numbed by her reply. He could hardly recall now what he had said or how he had behaved toward her. Had his natural courtesy of manner prevented him from showing the horror and disgust that he had been feeling?

Merrick watched the snow outside the window become wetter. Soon it would melt off the roadways. There was the faintest chance that by late afternoon it would be possible to travel again. But the thought brought no comfort. He would be going nowhere for the next few days, not until after his wedding, and then he would have to make arrangements for his wife to travel with him. His wife! That little drab of a girl who even now looked to him all the world like a servant. What was he to do with her? He could not possibly take her back with him to London. The very thought of being seen with her by all his acquaintances, of having to face Lorraine with her,' made him feel nauseated.

And as he stood there by the window, a faint suspicion began to form in Merrick's mind and to grow by the minute. He had fallen surely into a cleverly laid trap. Miss Anne Parrish might be completely lacking in feminine attractions, but she had considerable intelligence. She must have seen almost immediately the night before how she could turn the situation to her advantage. She must have seen that he had mistaken her for a servant, yet she had made no attempt to correct his error. She had played along with his mistake, acting the part with great skill. She must have realized, little dowd that she was, that this was the great chance of her life. If she could only seduce him-yes, indeed, it was she who had been the seducer-she would be able to force him into marriage.

She had succeeded, of course, much better than she could have expected. She had kept her honor intact and yet still won her point. Perhaps she had realized that, too. She must know her brother and that vicar fellow pretty well. She would have realized that in their narrow-minded view of life even the fact that he had spent the night in the same house as she would mean that her honor had been compromised. It had really been easy for her. All she had had to do was ensure that he stayed at the house all night and long enough the next day for her brother to come home and find him there.

The more he thought of the matter, the more Merrick was convinced that he had discovered the truth. Why else would the girl have accepted him with such little reluctance? Of course, he had introduced himself the night before by his title, obviously a great mistake. He was wearing his most fashionable and expensive clothes. He must have appeared a great catch indeed. And what a foolish one! He might have known that country morality was far more straitlaced than that to which he was more accustomed. He should have pressed on the night before after warming himself in the house. She had told him that the village was a mere three miles away. It surely would not have been impossible to travel that far. But, of course, he could not have been expected to foresee the danger; he had taken her for a servant. And he could not really blame himself for that. She certainly looked every inch the part, and she was a skilled actress. Only her speech might have given her away.

Merrick found that he was clenching and unclenching his hands at his sides and that his teeth were so firmly clamped together that his jaw ached. It was all true. Reality was beginning to establish its hold on his mind. He was not dreaming. Within the course of a few hours, his whole life had changed. All his dreams and plans for the future were ruined, and his new plans hardly bore contemplation. He had committed himself to this girl and would have to marry her. But he was damned if he would pretend to like it. His life might never be able to take the course that he had planned, but he was not going to allow the scheming little chit to ruin it altogether. She would be made to feel very sorry indeed for what she had done. She might bear his name and his title, but she would gain nothing else from this marriage if he had anything to say in the matter.

************************************

Anne Parrish and Alexander Stewart, Viscount Merrick, were married two days later in the village church. The Reverend Honeywell officiated, and Mrs. Honeywell and Bruce Parrish witnessed the ceremony. No one else was present or even knew of the wedding. The new tenants of the house had not yet arrived, and the present occupants had been nowhere during the days that intervened between the morning after the storm and that of the nuptials. The vicar's wife served tea and cakes in the vicarage afterward, but the viscount refused the offer of a wedding meal. He had hired a carriage with which to take his bride to his home in Wiltshire and intended to start without further delay. Even so, the state of the roads made it uncertain that they would complete the journey before nightfall.

Anne had never thought that she would feel sorry to say good-bye to her brother and to the home where she had never known much of happiness. But she felt something very near to panic as the shabby coach, the best the village had for hire, drew away from the gate of the vicarage and the group of three standing there waving to her. Only then was it fully borne in on her that the man beside her-her husband-was a stranger. And a very quiet stranger at that. In the last couple of days, though they had occupied the same house, they had spent almost no time in each other's company and no time at all alone. She had been busy in the kitchen much of the time. He had spent a great deal of time outside, either in the stable endlessly grooming his horse or in the grounds of the house trudging through the snow. He had spent very little time even with Bruce, seeming to prefer to be alone.

And that morning he had sat beside her in the coach, the same one in which they traveled now, Bruce on the seat facing them, saying not a word, making no attempt to touch her, or to smile at her, or to offer any sign at all that she was his bride and that they were on their way to be married.

Her bewilderment had grown during those two days to the point at which she did not know what to think. All the charm that he had used in the library when he had asked her to marry him had disappeared without trace. Since that time he had shown no interest in her, had acted indeed as if he were unaware of her existence. Yet he had made no move to explain to her that he had not been serious about his offer or that he regretted it and wanted to withdraw from his commitment. Why had he offered? He must have wanted her when he spoke to her. Was he perhaps merely feeling awkward at being trapped for a few days in a house without a change of clothes and without any of the people he knew? Yet it had been his decision that they marry there in such haste.

Perhaps now that they were on their way to Redlands-his home, about which she knew nothing except the name-he would be different. Sh

e waited for him to speak, to turn to her with some warmth. She expected him to begin to tell her about his home and family, about himself. Yet he sat straight on his seat, not touching her, looking out onto the dull world of melting snow and mud. And Anne dared not speak herself. She could think of nothing to say that would be sure to break down his reserve. So she stared out of her window, tense, uncomfortable, feeling the silence grow between them like a tangible thing.

Chapter 4

Viscount Merrick and his bride arrived at Red-lands at dusk. They were quite unexpected. The butler, Dodd, and the housekeeper, Mrs. Rush, always ran a strict establishment. No holland covers over the furniture in the best rooms for them. The servants were kept as busy when the master was from home as they were when he was in residence. The house was kept as immaculately clean. But it was a shabby house. The viscount had never made it a principal residence and had never taken any great interest in its decoration or upkeep. The gardens, similarly, were kept neat around the house by a hardworking gardener, but no one had ever taken the initiative to make anything beautiful of the extensive grounds.

When a dilapidated carriage was seen, then, by a groom, to be driving toward the house, and when the master himself was seen to alight and to turn to help a lady to descend, there was considerable excitement and curiosity, but no panic. Dodd pulled at his waistcoat to make sure that it was free of creases, and smoothed back the little hair that remained to him. Mrs. Rush shook out her white apron and inspected it quickly for spots. She ran her hands around the lacy brim of her cap to make sure that it was straight on her head. Both were standing in the hallway, flanked by the marble busts that had been painstakingly collected by the former viscount, when a footman finally opened the door to the travelers. Dodd bowed stiffly from the waist; Mrs. Rush curtsied, her lined face wreathed in a smile of greeting.

"Welcome home, my lord," Dodd said in his most stately fashion.

"Such weather, my lord," Mrs. Rush added. "We must be thankful to the good Lord for bringing you safely here."

Both glanced curiously at Anne.

"May I present my wife, the viscountess?" Merrick said, and watched with unsmiling eyes the quickly concealed amazement of the two elderly and faithful servants. He must become accustomed to such reactions, especially from those who would see her. Fortunately for himself, he did not intend that many people would do so-for the present, at least.

Mrs. Rush jumped into action. "You will be cold and tired, my lady," she said. "Come to the drawing room. There is always a fire in there from early afternoon. I shall have a tray of tea brought up to you at once. You must be longing for one. I shall have your bedchamber made up immediately and some nice hot bricks put between the sheets." She was already bustling up the wide curved staircase ahead of her new mistress, while Merrick lingered in the hall to give some instructions to Dodd and to see that his wife's boxes were removed from the carriage and carried upstairs.

Anne was feeling tired and bewildered. The journey had been a tedious one. They had made only one brief stop for a change of horses. Although she had had tea, she had not been invited to alight from the carriage. The refreshments had been brought out to the carriage for her. The atmosphere had not improved as the day advanced. Her husband had remained silent. She did not believe that they had exchanged ten sentences during the whole journey. It was puzzling and hurtful. She knew that she should have said something, asked him what was the matter. She should have done so before the wedding ceremony, in fact. There was certainly something very strange about his attitude. But she had not done so. She was far too timid. It was very easy in her mind to be positive, to take the initiative. In real life she allowed herself to be swept along by the plans of other people.

Now she found herself in the very uncomfortable position of being in a strange house, of which she supposed she was now mistress, with a strange man who was her husband but whom she knew not at all. And she had the growing suspicion that he did not really welcome her presence. However, as she followed the housekeeper up the stairs and along the hallway to a warm and large drawing room, she felt a measure of comfort. Mrs. Rush was friendly and seemed genuinely concerned for her comfort. She chattered constantly as she walked. Anne smiled with gratitude as she allowed her gray cloak and bonnet to be removed and a chair to be drawn closer to the dancing flames of the fire. It seemed to be years since anyone had fussed over her. Their servants at home had been chosen by Bruce and generally had his own sternness of manner.

"Thank you, Mrs. Rush," she said. "I have never been so glad in my life to see a fire. All I need to complete my happiness is a cup of tea."

The housekeeper smiled back. "I shall have a whole pot sent up right away, my lady," she said, "and a plate of currant cakes that Cook made fresh this afternoon. It was almost as if she knew you were coming."

She bustled from the room and soon had the cook and two chambermaids rushing around to produce the promised refreshments without delay. All the while, she gave it as her opinion that the master had chosen himself a very good sort of a girl for a bride. Not one of your grand ladies that was all frills and curls and never a sensible or a kindly thought in her mind. "Though I was never more surprised in my life," she added. "I always expected that his lordship would marry a beauty. In fact, it has been rumored that he was about to get himself betrothed to a marquess's daughter. I can't think why he has suddenly gone and got himself wed to someone we have never heard of. She has only two trunks, too, and no maid. But a very sweet lady, if my judgment is correct."

No one suggested that perhaps it was not. Mrs. Rush's word and her opinion were law belowstairs at Redlands. Only Dodd would ever have dared to dispute any of her pronouncements, and fortunately for the peace of the house, these two leaders of the household almost invariably agreed on all major topics. Thus it was that Anne Stewart, Viscountess of Merrick, was favorably received by the servants of her new home, at least.

She was unaware of this, however, having felt only the early kindliness of Mrs. Rush. She drank her tea and ate her cakes alone in the drawing room, gazing around her almost timidly, as if she were spying into a place where she had no business to be. Her mind registered the largeness and airiness of the room, which was somewhat spoiled by the shabbiness of wall tapestries that had been bleached by the sunlight of most of their color, of carpets that were worn in the places where they were most trodden and therefore most exposed to view, and of furniture that was heavy and inelegant. Strangely, it was a cosy room, but she felt strongly that it must be a long time since anyone had taken any real pride in the appearance of the house. The fact surprised her. Even in the gathering dusk, she had been able to see as they had approached the house that it was far more magnificent and the grounds far more extensive than even she had pictured them in her imagination.

She did not know what to do when her second cup of tea was finished and still she was alone. She began to have painful visions of being forgotten there and of finally having to make up her mind to leave the room and find out where she was to go next. It was with great relief that she turned to the opening door and saw Mrs. Rush bustle in again.

"If you are warm and ready to leave the fire, my lady," she said, "I shall show you to your chamber. You need not fear that it will be unaired. I always see to it that there is a fire in the room twice a week and that bricks are put into the bed just as often. You will find a cheerful fire there now, and Bella has unpacked your boxes already and had everything put away for you. She will be your maid until you wish to make other arrangements. His lordship says that will be suitable, and I am sure that you will, like Bella. She dresses a head better than any ladies' maid I know, and she is a very cheerful sort of a girl. She does not talk your head off when you are trying to think of other things, like some servants I could name."

Anne smiled and allowed herself to be led away and to be fussed. It was from the housekeeper that she learned that dinner would be served at eight, and that presumably she would see her husband again that ni

ght. She had begun to wonder. Certainly it was proving to be a far stranger wedding day than she had ever imagined. Even during the past two days, when the viscount had been so silent, she had imagined that everything would be well once they were married and alone. She had conceded that he was in a very awkward position, living in a house that was not his own, constantly in the presence of her brother whenever he came indoors. He would be smiling and charming once more after their wedding, she had thought, and would show once again that he appreciated her as a woman. But she still waited.

************************************

The meal proved to be as painful as the journey earlier in the day had been. They sat in a very formal dining room at a table that would have seated twenty quite comfortably. Merrick sat at one end, Anne at the other. Even if they had wished to converse, they would have had to raise their voices to an unnatural pitch. But they exchanged hardly a word. Anne was constantly aware of the butler and a single footman almost ceaselessly walking between them bearing bowls and tureens, removing dishes of food that had hardly been touched. She looked anxiously down the table when the last course had been carried away. Did he expect her now to leave him alone with his port? Fortunately, Merrick picked up his cue on this occasion.

"I have given instructions that the fire in the drawing room need not be built up," he said. "I assume you are tired after our long journey?"

"Yes, my lord," she agreed. "I shall be glad to retire early to bed." And she blushed as she said the words. Was this part of the wedding day, at least, to be normal? Was there to be a wedding night? She noticed with sudden clarity his extreme handsomeness. He was no longer in the expensive but severe riding clothes that he had worn for the last several days, including his wedding, but in a russet satin coat over a gold brocade waistcoat and crisp white shirt with an elaborately tied neckcloth. His near-black hair was freshly washed and was brushed back in thick, soft waves from his face. The severity of his expression merely served to emphasize his quite devastating good looks.