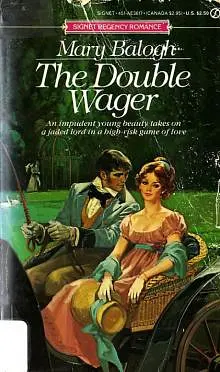

by Mary Balogh

"We have not had our history lesson today," Miss Manford protested.

"Oh, Manny, I can take the book with me and read while I watch," said Philip. "Are you coming, Pen?"

"Who is to look after Cleopatra?" she asked. "The poor little thing is feeling so strange and Oscar has been so rude to her."

"Well, she does stink a little bit, Pen," her brother said. "I shall go alone, then."

Philip, in the true spirit of the drama of the situation, as lie saw it, went first to his room and changed into the urchin's clothes that he had worn the night before, and then tiptoed quietly into the empty room opposite Henry's. Ile settled himself in a chair from which he could see the handle edge of her door through the door of his room, which he left slightly ajar.

Thus it was that Philip saw Henry slip from the house and was all ready to follow her. He did so without hesitation. It was obvious to him as soon as he saw her unusually drab outfit and as soon as she turned in the direction of the back stairs, that she was on some secret errand. He held her very carefully in sight until she hired a hackney cab. For a moment Philip was alarmed. He thought he would lose her. Fortunately, there was time after Henry got into the carriage and before it moved away for him to run forward and swing himself up behind. The driver did not notice, and none of the passersby seemed to consider his actions strange enough to raise any alarm.

Chapter 11

Henry sat in her room later the same afternoon, looking flushed but triumphant. She was at a small escritoire, writing a letter. A small collection of crumpled sheets of paper surrounding her on the floor showed that the words of the letter were not coming easily. This time she seemed satisfied. She signed her name with a flourish, shook the paper in order to dry the ink, and reread what she had written.

Dear Mr. Cranshawe [she had written, having discarded the notion of calling him Oliver],

I am now able to repay my debt to you. I thank you with all my heart for having helped me out of a difficulty. You will find three thousand pounds enclosed in this package.

I remain your grateful friend,

Henrietta Devron

Yes, that was quite enough, she decided. She did not need to say more. There was just the correct combination of gratitude and reserve. She folded the letter, slid it into the package with the bank notes, and tied the bundle securely with ribbon. She rang the bell for Betty.

"Betty," she said when her maid entered the room a few minutes later, "which footman is most reliable to send on a secret and important errand?" Henry did not mince her words. She had learned from experience that Betty was devoted to her and could be trusted to keep her secrets.

Betty did not hesitate. "Robert, your Grace," she said.

"Good. Will you send him to me?" Henry directed.

Within ten minutes Robert had been sent to Oliver Cranshawe's residence with the package. The footman had strict instructions to deliver it into the hands of Cranshawe himself or, failing that, into the hands of his personal valet. He was not to wait for a reply.

Henry breathed a deep sigh of relief when the deed was finally done. What a delicious sense of freedom there was in being out of Oliver's clutches at last. He would probably he furious to see her slip through his fingers, she thought grimly. But he could hardly refuse the money. And with that debt repaid, she would no longer be obliged to jump whenever he snapped his fingers. In fact, she decided, she would not need even to be civil to the man. Marius would be pleased to see that their friendship had finally cooled. Not that she had any interest at all in pleasing her husband! Her hands curled into fists as she thought again about her abandonment to his lovemaking the night before and his cool rejection of the morning.

Henry summoned Betty again and had hot water brought to her room for a bath. She relaxed in the water while Betty laid out her turquoise satin and lace evening gown on the bed behind her. For the moment she felt relaxed. She could get ready for dinner and the opera almost with a light heart, though it would be difficult to spend a whole evening in close contact with Marius. But at least, she thought with a little smile of genuine amusement, she would have the satisfaction of knowing that he was not enjoying himself. Marius and music did not mix happily together.

Tomorrow she would think about her new problems, for, truth to tell, she had merely exchanged one nasty difficulty for another. She tried not to think about her dealings of earlier that afternoon. She had felt horror when the hackney cab had turned into narrow, filthy streets filled with all kinds of offensive rubbish and smells. Doorways and roadsides had been crowded with untidy and dirty-looking people and ragged children. When the carriage had stopped, she had not known what to do for a few moments. But, remembering that she was Henry Devron and had never been afraid of anything for long, she got resolutely out of the carriage with the driver's assistance, instructed him to wait for her, squared her shoulders, and bore down on a small group of women gossiping in a doorway.

They had gawked at the sight of her fine clothes (the gray cloak and brown bonnet had looked drab enough back on Curzon Street, but not here), but had directed her readily enough to the first-floor rooms of the money lender. She had given them each a shilling for their help and had been followed by openmouthed stares to the dark doorway of her destination.

Henry shuddered now in the bathtub remembering those dark, dirty stairs and the smiling, sinister little man who had opened the door at her knock and bowed her into a dingy room whose door he had proceeded to lock. The interview itself, though, had not proved as difficult as she had expected. The little man had been quite willing to lend her the money, especially when he knew who she was (she had decided not to lie, believing that he would more readily agree to do business with a duchess than he would with a Miss Nobody). Henry had eagerly signed the papers, not at all deterred by the interest rate, which she did not understand. The only nasty moment had come when the moneylender had demanded a pledge of security.

"But I have nothing!" she had protested. "You must trust me."

"But of course I trust you, your Grace," the little man had said, smiling all the while. "Such a charming lady must be honest. But you see, my dear, I do not work for myself. My superior is a hard man, a hard man."

"I do not believe you," Henry had declared hotly and none too wisely.

"Oh, but, dear me, it's a fact," the little man had said, rubbing his hands together, his grin never faltering. "But for such a pretty and grand lady, a mere token. What jewelry do you have, my dear?"

"None!" was Henry's prompt response. "And my purse is almost empty, sir. If I had wealth to leave as security, Would I be here borrowing money?"

"Oh, dear me, such a spirited young Jady," he had said. "You wear rings, my lady. One of them will serve the purpose. A mere token, you see."

Henry's eyes had widened. "You cannot have either," she said, glancing down at the gold wedding band on her left hand and the sapphire on her right. It was unthinkable to pledge the wedding ring. The other had belonged to her mother and had been left to Henry. Ever since her hands had grown large enough, Henry had worn it. She hardly ever removed it.

In the end she had pledged the sapphire ring. Now she felt sick looking down at her soapy hand and seeing it bare. For her own sake she hated to be without it. Perhaps more important for the present, she was afraid that Marius would miss it and ask her for an explanation. She might as well have pawned more of her jewels for the whole sum, she reflected gloomily.

But she shook off the gloom. She would think of some explanation to give Marius. And tonight she was going to celebrate her freedom from Oliver Cranshawe. Tomorrow she would worry about her new debts.

**********************************************************************************

Miss Manford, in the schoolroom, was showing unaccustomed firmness.

"No, my dears," she was saying, "we cannot handle this matter ourselves. The poor dear duchess must be in terrible trouble if she has resorted to appealing to a money lender. I have heard that they ar

e dreadful people."

"But we can watch after her, Manny," Philip protested. "As long as one of us stays close, she can be in no danger. I stayed outside that house while Henry was inside. If she had not come out within a few minutes, I planned to stir up those people in the street and wail loudly that my sister had been kidnapped. I would have scared the of money leech."

I think not, dear boy," Miss Manford said. "Those people would have kept out of trouble, you may depend upon it. No, we must enlist the help of someone who can offer real assistance to dear Hen-I mean, to her Grace.",

"Well, she would never have gone there if she felt shr could have turned to the duke," said Penelope. "And I cannot understand why. He seems to me to be ever so kind. Brutus, will you stop licking Cleopatra all over? She will take a chill."

It was finally decided that two adults would be consulted. Miss Manford declared that she would talk to Mr. Ridley the next day; Philip and Penelope were to summon Giles and tell him the story. None of them was willing to seek help from Sir Peter Tallant.

**********************************************************************************

The Duke and Duchess of Eversleigh dined alone that evening and consequently were seated in their private box at the opera a good ten minutes before the performance began. Henry let her eyes rove over the pit, which was already crowded with noisy, exotic-looking dandies. It seemed obvious to her that very few of them had come out of a love of music. They were there to ogle the ladies in the boxes and to preen their male feathers before them. The occupants of the boxes seemed similarly inclined. They were there to see and to be seen. How many of them would remember more than the name of the opera once it was over?

Henry smiled to herself. The opera and its artiste would be the topics of polite conversation the next day. Everyone would be an expert critic. The smile faded when she met the stare of Oliver Cranshawe from across the way. He was sharing a box with Suzanne Broughton and two other couples, Henry noticed at a hasty glance. He smiled and bowed in her direction. Henry inclined her head stiffly in return. He did not at all look like a man who had just lost it war, she mused. She felt Marius beside her bow in the direction of a smiling Mrs. Broughton. Henry, giving no visible sign that she had even noticed the exchange, wished heartily that the woman were within reaching distance so that she could gouge the smile out of her beautiful face with her fingernails.

Eversleigh's hand reached out and took her right one in his. "I have not told you how lovely you look this evening, my love," he said, turning his attention to her. "It is a new gown, is it not?"

"Yes," she said, and for once was lost for words. The blood was hammering in her head as she tried to remove the ringless hand from his grasp without jerking it away and attracting undue attention.

"Where is your ring?" he asked, and Henry let her hand fall limp in his.

"What ring?" she asked, looking up at him and flushing, furious at her own response.

His lazy blue eves looked into hers and the lids dropped farther met their. "Your mother's sapphire, I mean, Henry," he said softly. "Where is it?"

"Oh, that ring!" she said with false brightness. "I took it off tonight. It did not match my outfit, you see."

She looked down into the pit again and smiled briefly at a gallant who had a quizzing glass directed her way. She could feel her husband's glance boring into her. "A sapphire ring does not suit the turquoise of your dress?" he said. "Henry, my love, you must be color-blind."

She did not reply.

"Have you lost it?" he persisted.

"Oh, no," she said with a trifling laugh that sounded false even to her own ears. I remember now. I took it to a jeweler's to have the setting checked. It has never been checked, you know, and I have been afraid that the stone might fall out. I should be dreadfully upset. you know, if I lost it. It is the only memento I have of Mama. I hate to be without it for a while, but it seemed-"

"Hush, my love," Eversleigh said gently, clasping more warmly the hand that he still held, "the orchestra is about to begin playing."

Henry felt her heart gradually slowing to a normal beat as she tried to concentrate on the overture that the orchestra was playing. But she was uncomfortably aware for some time that her husband was still looking at her.

The usual court of young men came to pay their respects to Henry during the first intermission. Eversleigh stayed with her until his cousin, Althea Lambert, with an escort, arrived to visit. Then he strolled away, leaving the young people to their own chatter.

Only a few minutes had passed before Oliver Cransh~we appeared in the box. Henry was aghast; she had not thought he would have the nerve. Perhaps he had not yet received her letter and the money, she thought.

"Althea," he drawled after bending low over Henry's hand and kissing it, "how delightful to see you. Er, I do believe Lady Melrose was looking for you a moment ago. Something about a rout, I believe?"

"Oh, that will be her Venetian breakfast," Althea said, brightening visibly. "Yes, indeed, she did suggest that I

be a hostess with her daughter. Come, Mr. Rawlings, let us go to her at once."

Mr. Rawlings dutifully led his charge away and Henry was momentarily alone with Cranshawe. The other three men in the box were deep in conversation about a horse race that was to be run the following afternoon.

"Did you receive my package, sir?" Henry asked frostily, deciding that it would be best to go on the attack.

"Yes, indeed, cousin," he said, giving her the full benefit of his most charming smile. "How delightful to know that you have come about so soon."

"Yes, well, I told you I should pay you back as soon as I was able," she said.

"I wonder how you managed quite so soon, though, Henry," he said. I hope you have not lost your trust in our friendship and put yourself in debt to someone else."

"That is none of your concern, sir," she said spiritedly. "All that concerns you is that you have recovered the full sum that you loaned to me."

His eyebrows rose in surprise. "Oh yes, almost," he said. "I shall not press for the remainder, of course, but then I did assure you that there was no haste for you to repay the principal."

"The remainder?" Henry asked faintly.

He looked puzzled. "But I have lost money while the three thousand was in your possession," he explained. A must, of course, recover the interest. But I do not wish you to worry your pretty little head over it, Henry. There is no hurry at all. In fact, I should be quite willing to take the loss if you would care to repay me in, er, some other way.

"What do you mean?" she whispered.

He smiled directly into her eyes as he answered. "A night with you, Henry."

Henry's mouth dropped open. "Where?" she asked naively.

The smile broadened. "In bed, obviously, my dear."

Henry was saved from the ignominy of being seen to jump to her feet and smack the face of Mr. Cranshawe in that appallingly public setting. As she was about to respond to the impulse, she was aware of Eversleigh stepping back into the box. His eyes found her face immediately and took in its expression. His eyelids drooped over his eyes as he strolled forward.

"Ah, Oliver, dear boy," he said languidly, "you are becoming quite the stranger these days. It seems quite a while since you invited yourself to breakfast last."

"I have the distinct impression that I was not welcome the last time I came, Marius," said Cranshawe, an edge to his voice.

Eversleigh raised his quizzing glass and surveyed his heir unhurriedly through it. "Indeed?" he said. "What can have given you that impression? Ridley was there, was he not? I cannot remember his being rude to you. There was the matter of newspaper being left behind, though, was there not, dear fellow? It is still there for you to claim." He let the glass fall to his chest again.

"You are too kind, cousin," Cranshawe said through his teeth.

"Not at all, not at all, dear fellow," said Eversleigh. "You must give me the honor of your company as well as my wife, you know. In f

act, dear boy, I must insist that you announce your visits so that I may not be deprived of the pleasure."

"The second act is about to begin," Cranshawe mumbled, getting to his feet and bowing stiffly. "Your Grace?"~

Henry nodded, but she did not look up. The ether 0 three gentlemen also crowded around to make their farewells.

As Henry turned her chair to face the stage again, Eversleigh took her hand and laid it on his sleeve.

"I wish to leave," she said, eyes riveted to the stage. "Please take me home, Marius."

"No, my love," he replied gently. "We must be seen to sit here in amicable agreement."

His words hummed in Henry's mind as the music and singing washed over her. What had he meant? Was there already talk about her and Oliver Cranshawe? Was Marius trying to avert it?

****

The Duke of Eversleigh walked into his secretary's office the next morning before luncheon. He was still clad in riding clothes.

"Ah, James," he said, "bow predictable you are, dear fellow. One can always depend upon finding you here."

"Well, you do pay me to work here during the daytime, your Grace," Ridley replied patiently.

"Quite so, dear boy," Eversleigh agreed, "though I seem to remember giving you an assignment yesterday that should have had you up and abroad."

"I have already done my best on that mission," his secretary replied, "and devilish difficult it was too, sir, if you will excuse me for saying so."

"Oh, surely, James," the duke replied, waving a hand airily in his direction. "And what did you discover?"

"I can find no trace of any debt incurred by her Grace that has not been sent here," Ridley said.

Eversleigh regarded him thoughtfully. Hmm, he said. "Are you sure your information is complete, James?"

Ridley shrugged. "I talked to the persons most likely to know about any gambling debts," he said.

"My wife is missing a ring that she almost never removes from her finger," Eversleigh said almost to himself, strolling over to take up a stand in his favorite spot, one elbow propping him against a bookshelf.