“We will go this afternoon,” she said in matter of fact tones.

“Go where, child?” he asked her.

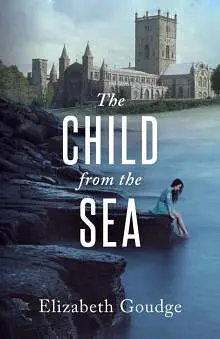

“On pilgrimage to St. Davids,” she said, “To the Cathedral and the shrine.”

Old Parson began to shake for he remembered now what it was that had flung him headlong into sorrow; the mention of that shrine where men received forgiveness. He had known about it for a long time but he had never dared to go there. He had always been afraid that as soon as he came anywhere near the holy place lightning would strike him down for his presumption.

“Would it be possible?” he whispered to Lucy. She thought he was referring to the long walk and his physical weakness. “Yes,” she said. “We will ride there. I will bring the ponies and fetch you after dinner.” Then suddenly she broke into a peal of laughter. “Oh look!” she cried, pointing. Her Sunday hat that she had tossed upon the tomb had landed upon the head of the dog who lay there recumbent at his master’s feet, an amiable mongrel dog who bore a strong resemblance to Rhys. He looked very comical in a hat. Old Parson, who could still laugh with the children at what made them laugh, laughed with her. He had a small almost soundless laugh, like the creaking of the last two autumn leaves left on a wintry twig. Seeing him happier Lucy retrieved her hat and led him from the church. They went hand in hand along the sun-dappled path through the now deserted graveyard, the trees a grateful coolness over their heads.

2

When the formal, dignified Sunday dinner was over fate played into Lucy’s hands. She had not known how she would manage to evade the Sunday afternoon gathering of the family to make music in the arbour, but as they rose from table Elizabeth complained of a headache and said she must lie down. “Madam, I will get you mint leaves to take away the pain,” cried her daughter, and all in a loving flurry she seized Justus by the wrist and raced with him down the hall and out into the garden. The mint grew obligingly near the door into the lane. She grabbed a bunch of leaves and pushed it into Justus’s fat hand. “Stay here for ten minutes and then take it to our mother,” she commanded. “Tell them you’ve left me in the arbour and later, if they worry, tell them I shall be coming back.”

“Where are you going?” demanded Justus, his cheeks already crimsoning with the anger he would feel if she was going on an adventure without him.

“I cannot tell you now but I will tell you afterwards,” she said, and gave him a great hug. “You will do what I say because you love me,” she whispered against his hot cheek, where already tears of fury were beginning to trickle. Then she closed the door in his face and ran like the wind to the stable. She heard him beginning to roar but she knew he would do what she said because for him obedience, even furious obedience, was the way of love. She knew just what he would do; sit on the grass and bellow for the stipulated time and then wipe his face on his sleeve and trot indoors with the mint. As she ran she grieved that she had told that lie about waiting in the arbour. It had popped up out of the repressed resentment of the morning, like a pea out of a pod. Sins did pop out one from the other in that way. It was a habit they had. Well, her hurt feelings had exploded now and apart from the lie her virtue was not in question, for Parson Peregrine had said it was a good and holy thing to go on pilgrimage.

She took the ponies’ harness from the harness room and ran out to the field beyond where they were grazing. There was a joyous whinnying when she appeared but she could not stop for conversation. “Prince,” she called. “Jeremiah.” Richard’s white pony Prince was his private property and he would not allow the younger children to ride him. They had to make do with Jeremiah the kitchen pony who pulled the faggot cart and carried panniers full of apples in the autumn. Richard’s selfishness over Prince was something Lucy resisted whenever possible, and she and Prince were mutually attached, but it was Jeremiah whom she most deeply loved and he came to her now as fast as he was able. He was old and stout but could still do a hard day’s work because he was a mountain pony, wiry and strong, and at one time had been very wild. The wildness had been trained out of him but independence of character was still a marked characteristic. He was of comical appearance, piebald with the black patches very oddly placed, one across his face like a mask and the other across his broad back like a saddle. His eyes were surrounded by stubbly white lashes and were always very bright. Prince followed him closely, his long tail drifting out on the mild air like silver spume, his neck arched like a sea horse. Lucy harnessed them quickly and jumped on Prince’s back and they were off. She did not have to lead Jeremiah for he followed like an old dog.

Old Parson, with Rhys beside him, was standing on the bridge but not waiting for them. He scarcely seemed aware of their arrival, though when Lucy slipped off Prince and took his hand his long cold fingers enclosed hers gratefully. He was watching for something, or rather the return of something, the expression of his face like that of a baby who has seen the gold watch swing one way and waits for the return of the miracle with awe and ecstasy. It came, the blue flash of a kingfisher from bank to bank below the mill, so rapid that the colour seemed still in the air, like a rainbow over the stream. Old Parson had forgotten all about the pilgrimage but now, with Lucy’s hand in his, he remembered it, and the blue bow seemed almost like a promise that the arc of God’s mercy might not always be only for other men. “We will go now,” he said to Lucy. She had her arms round Rhys, who was standing on his hind legs, his fore paws on her shoulders and his tail whirling around in circles almost as rapid as that of the kingfisher’s flight. He wanted to come with them but they had to leave him behind, for his wounds were too sore for a long journey on a hot day.

They rode off at a good pace. Old Parson must at one time have been accustomed to the saddle for he seemed quite at home there, and although Lucy’s Sunday dress was not very suitable for riding she was such a natural horsewoman that she could have ridden anything, anywhere, anyhow. It was ten miles to St. Davids and though Lucy had been there before it had been only in the coach with her mother, to a service at the Cathedral and to some party at a house in the village and she was always restless and irritated in the slow lumbering coach. But this journey was so entirely different that it seemed a journey through a strange land to an unknown city, as unknown to her as to Old Parson.

Yet she had one vivid memory of a previous visit, something that floated free of the spreading skirts and large hats that had hemmed her in. It was a small clear picture of tall pillars that went up into blue shadows, and lifted up among them a little man, black and white like a magpie in a nest. He stood up in the nest, lifting his arms like wings, and spoke, and when he spoke the rustlings and whispers fell silent, for he was a famous preacher. She could remember the silence, and his voice that was clear and loud. She had not understood what he said but she had sat gazing at him, hugging herself with glee as she remembered the story of his conversion, that she loved as well as any among the sagas of Wales. For the instrument of Chancellor Pritchard’s conversion had been a mountain goat. Lucy loved the wild mountain goats of Wales, big as donkeys, and she was sure God loved them too or else why use a goat to convert Chancellor Pritchard? As they trotted along she told the story to Old Parson, enriching it with a wealth of detail accumulated by her lively mind over many tellings.

When Chancellor Pritchard had been Vicar Pritchard of Llandovey he had been a very merry man. Parsons were forbidden to enter a public house, or to touch cards or dice, but Vicar Pritchard had done all these things and had enjoyed them enormously. So very merry had been his nightly carousels at the village inn that a special wheelbarrow had been kept for wheeling the parson back to bed at night. He had been travelling home one evening, pushed by other merrymakers, his legs stretched out in front of him, his voice upraised in song and the wheelbarrow zigzagging from side to side, when he beheld in front of him, blocking the narrow lane, a large inebriated goat, blue-grey in colour and terrifying in appearance. Though it was not so much the great horns and hoofs and th

e long yellow teeth that horrified Vicar Pritchard as the spectacle of its inebriation. Its drunken bearded face seemed to him a reflection of his own and as he and the wheelbarrow rocked from side to side so the goat reeled from side to side, the hairy countenance coming always nearer and nearer to his own. It was when the creature’s hot breath was actually in his face that he screamed with terror, leaped out of the wheelbarrow, raced up the lane to the vicarage and was not seen again for a fortnight. When he emerged he was a changed man, a man of penitence and prayer, and now he was Chancellor of St. Davids Cathedral and the greatest preacher in the principality. Yet he still had a merry heart and still he liked to sing. They sang his hymns all over Wales.

“Was he forgiven?” asked Old Parson anxiously. “Did the scapegoat take away his sin?”

This was an aspect of the affair that Lucy had not thought of before. “I don’t know,” she said slowly. “I had not thought of that goat being a scapegoat, like the sin-eater.”

And they began to talk about their friend up in the mill wood. For he was Lucy’s friend too now. Old Parson could not always climb as far as the hiding place by the big stone and so now Lucy did the climbing for them both, carrying up the scraps of food that Old Parson collected or that she herself begged from the cook at the castle. Nan-Nan’s eye upon her was very vigilant these days but she and Richard had organized another escape route. He and the young fisherman with whom he sometimes went for early morning fishing expeditions had made a rope ladder which could be let down from the window in the boys’ turret room, as far as the old fig tree which grew up the castle wall below. The descent was long and perilous and the manner in which the ladder was fixed to the crumbling stone upright in the centre of the window none too secure, and Richard did sometimes wonder if the fishing was worth it.

Lucy never doubted that the sin-eater was worth it. He was not always in the wood when she climbed up with his food, whistling the special bird call that was her signal to him, but when he was there he no longer ran from her. When she spoke to him he would utter strange sounds and then look at her with anguish, as though he longed to speak but could not recapture the words that had been long forgotten. Though he had taken upon himself so many sins he was not evil, and his helplessness broke her heart. When she left the sin-eater she went home weeping not only for him but for herself too because she did not understand.

But she and Old Parson forgot sadness in the delight of the journey. Their pilgrim way led them first downhill to Newgale, where the sands fell away from the great pebble ridge that protected the cottages and the old inn from the Atlantic storms. Newgale could be a drear and terrible place in stormy weather but today the fishermen sat on the pebble ridge mending their nets, their brown backs gleaming like bronze in the sun. Then uphill again to a great sweep of open country, thyme-scented in the heat, the turf cropped short by the grazing sheep. From here they could see Roch Castle on its rock, the Prescelly mountains remote and cloudlike to the east, and to the west the blue sweep of St. Bride’s Bay. The off-shore islands looked unearthly today, half-veiled in the heat mist, bird haunted and mysterious. Inland the fields of oats and barley were ripe already and the light wind ran over them like the invisible feet of a multitude of elves. Here and there one-story white-washed cottages crouched behind thick ramparts of oaks and thorns blown almost horizontal, and then the way plunged downhill again into a deep valley, to the little port of Solva. Then up again and along the top, and almost before they knew it they were in the little city of St. Davids, and the way had become a lane winding between cottage gardens where lilies, tansy and bergamot grew, and the tassels of tamarisks hung over the low stone walls.

The lane brought them to the cobbled square where stone steps led to a high stone cross, and there was a drinking trough beside the inn door. They dismounted and the ponies, hot and tired now, drank gratefully while Lucy knocked on the inn door and demanded of the sleepy old man who opened it buttermilk and bara ceich, and stabling for the ponies while she and her friend went to the Cathedral. She asked politely but imperiously, drawn up to her full height, every inch a very great lady; all the more imperious because she had no money in her pocket. He did her bidding instantly and she and Old Parson ate and drank sitting on the bench at the door. It was much cooler now, as though the movement of the tide was once more towards them, and the blue shadow that stained the cobbles beneath the inn wall was deep as the note of the bell that tolled from somewhere near, yet sounded as far below them as the caverns at the bottom of the sea. Lucy did not count the notes of the bell for she never bothered about the passing of time when she was happy. Old Parson was not bothering either for this pilgrimage was like a causeway that lifted him above time, and above the confused and troubled self that belonged to time, and like Lucy he was happy.

Lucy jumped up and took his hand. They went down a cobbled lane to a massive arched gateway, and passed under the arch and stood upon the edge of another country; but they looked down upon it, not up at it, as though it were not paradise itself but a reflection of it mirrored on the earth. There was a wall here and they leaned upon it. This was the Valley of Roses, one of the places of power of which there are not many upon earth, and its living strength could smite even its familiar lovers with a perpetual shock of surprise. So ancient it was always new. The walls and pinnacles and square tower of the Cathedral, honey-coloured in the sun and violet after rain, seemed always to live and breathe with the movement of clouds and running shadows. The ruins of the bishop’s palace beyond, delicate with long arcadings of empty arches against the sky, could look in some lights like festoons of shifting mist. There were tall green trees down there, and emerald turf where sheep were feeding, and the flash of a stream going down to the sea. The quietness held the sound of the water and the murmur of sleepy birds. The nature of the land that held this hidden place was forgotten until one looked across the valley and saw a harsh rim of rock brooding black and jagged against the sky. Yet that harsh reality was no more real than this. It was more apparent, but not more real, for all mirrors, by their very nature, must reflect truth.

“We will go in,” said Lucy. She did not say go down, though that was what they would do, for a flight of steps descended towards the Cathedral, but go in, as of favour and invitation. An invisible door had opened for them. Hand in hand they went down the steps cut in the hillside to the green graveyard. They did not go at once to the Cathedral but walked to the stream, and stood on the old bridge that spanned it looking down into water so clear that they could see the pebbles on the bottom. The services of the day were over and there was no one about, only the dragonflies who pierced the sunshine with their jewelled dartings. They were close now to the roofless fourteenth-century palace and Lucy told Old Parson that it had been built by Bishop Gower, bishop of St. Davids and Chancellor of England, and stripped of its roof by Bishop Barlow, who had sold the lead to provide dowries for his five daughters who married five bishops. It was the achievement of Bishop Barlow rather than Bishop Gower that awed Lucy. Such fatherly affection seemed to her remarkable, but it was a pity it had destroyed the palace. “Yet it could not be more lovely,” she said to Old Parson. “In June the wild roses grow all over the ruins and the banqueting hall has a floor of grass and moss, and there are dark crypts down below. Richard and Justus and I played there once and we thought we heard other children calling to us, calling and calling, but they weren’t there at all, it was our voices echoing. And now we’ll go in.”

They went through the west door into cool peace and Lucy guided them to a bench. The first impression was of the muted silver and gold of a winter beech wood on a day of quiet sunshine. The gold slanted down through the upper traceries of the trees and lay in pools on the flagstones, and far overhead glowed in the old roof. The sense of a wood was increased by the tilt of the pillars, disturbed long ago, men said, by an earthquake, and the floor too was uneven, sloping upwards to where steps rose to the dark oak screen, pierced by an archway t

hat led to the holy places beyond. Above the arch the rood hung from the ceiling but so far away that the outstretched arms of mercy could be seen only dimly. But they could be seen, especially at this moment, for sunbeams were gathered there. Old Parson knelt down and prayed while Lucy took off her shoes and paddled her hot bare feet in the coolness of the stone floor. Once more a bell tolled, far above her now, up in heaven and not down below in the sea, and once more the passage of time was not important. Old Parson ceased to pray but continued to kneel, his childlike blue eyes following the play of the sunbeams about the rood.

“May God bless you.”

The quietly spoken words created no disturbance in the mind and Lucy and Old Parson turned their eyes only slowly towards the direction of a voice so musical that Lucy expected to find an angel there. But the grey-bearded man in a shabby cloak who stood beside her was too homely in appearance to be angelic, though he had an air of angelic authority, so much so that Old Parson got up from his knees and bowed and Lucy slid to her feet and curtseyed.