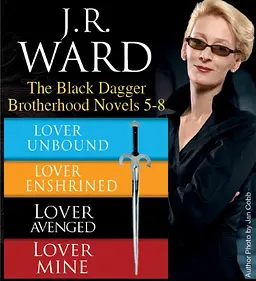

by J. R. Ward

Okay, what the fuck? It wasn’t that he didn’t like the thoughts he was having about her, but it was as if someone had switched his CD. And no, it wasn’t to Barry fucking Manilow.

Although there was definitely some Maroon 5 on the bitch now.

Bleh.

“Oh, I’ll just go, but thank you.” Ehlena paused in front of one of the sliding doors. “Tonight has been such…a revelation.”

Rehv stalked up to her, took her face in his hands, and kissed her hard. When he pulled back, he said darkly, “Only because of you.”

She beamed then, glowing from within, and abruptly he wanted her naked again just so he could come inside of her: The marking instinct was screaming in him, and the only way he could placate it was by telling himself he’d left enough of his scent on her skin.

“Text me when you get to the clinic so I know you’re safe,” he said.

“I will.”

One last kiss and she was through the door and off into the night.

As she left Rehvenge’s, Ehlena was flying, and not just because she was dematerializing across the river to the clinic. To her, the night wasn’t cold; it was fresh. Her uniform wasn’t wrinkled from having been tossed on a bed and rolled around upon; it was artfully disheveled. Her hair wasn’t a mess; it was casual.

The call to come into the clinic wasn’t an intrusion; it was an opportunity.

Nothing could take her down from this incandescent elevation. She was one of the stars in the velvety night sky, unreachable, untouchable, above the strife of the earthbound.

Taking form in front of the clinic’s garages, though, she lost some of her rose-colored glow. It seemed unfair that she could feel as she did, considering what had happened the night before: She’d bet her life on the fact that Stephan’s family wasn’t rebounding back to any semblance of joy right now. They would have just barely finished the death ritual, for God’s sake…. It would be years before they could feel anything even remotely like what sang in her chest as she thought of Rehv.

Or if ever. She had the sense his parents might never be the same.

With a curse, she walked swiftly across the parking lot, her shoes leaving little black prints across the dusting of snow that had fallen earlier. As a staff member, getting through the checkpoints down to the waiting room didn’t take long, and when she came into the registration area, she shucked her coat and headed right for the front desk.

The nurse behind the computer looked up and smiled. Rhodes was one of the few males on the staff, and definitely a favorite at the clinic, the kind of guy who got along with everyone and was quick with the smiles and the hugs and the high fives.

“Hey, girlie, how you…” He frowned as she got closer to him, then pushed his chair back, putting space between them. “Er…hi.”

Frowning, she looked behind her, expecting to see a monster, given the way he shrank from her. “Are you okay?”

“Oh, yeah. Totally.” His eyes were sharp. “How are you?”

“I’m fine. Glad to come in and help. Where’s Catya?”

“Waiting for you in Havers’s office, I think she said.”

“I’ll head on back then.”

“Yeah. Cool.”

She noticed his mug was empty. “You want me to bring you a coffee when I’m done?”

“No, no,” he said quickly, holding both hands up. “I’m fine. Thanks. Really.”

“You sure you’re okay?”

“Yup. Totally fine. Thanks.”

Ehlena walked off, feeling like an absolute leper. Usually she and Rhodes were pally-pally, but not tonight—

Oh, my God, she thought. Rehvenge had left his scent on her. That had to be it.

She turned around…but what could she say, really?

Hoping Rhodes was the only one who’d pick up on it, she hit the locker room to ditch her coat and headed off, waving to staff and patients along the way. When she got to Havers’s office, the door was open, the doctor sitting behind his desk, Catya in the chair with her back to the hall.

Ehlena knocked softly on the jamb. “Hi.”

Havers looked up, and Catya glanced over her shoulder. They both seemed positively ill.

“Come in,” the doctor said gruffly. “And shut the door.”

Ehlena’s heart started to beat fast as she did what he asked. There was an empty chair next to Catya, and she sat down because her knees were suddenly loose.

She’d been in this office a number of times, usually to remind the doctor to eat, because once he started in with patient charts he lost track of time. But this was not about him, was it.

There was a long silence, during which Havers’s pale eyes would not meet hers as he fiddled with the earpieces of his tortoiseshell glasses.

Catya was the one who spoke, and her voice was tight. “Last night, before I left, one of the security guards who had been monitoring all the camera feeds brought it to my attention that you were in the pharmacy. Alone. He said he saw you take some pills and leave with them. I looked at the tape and checked the relevant shelves and it was penicillin.”

“Why didn’t you just bring him in?” Havers said. “I would have seen Rehvenge again immediately.”

The moment that followed was like something in a TV soap, where the camera zoomed in on the face of a character: Ehlena felt as though everything pulled away from her, the office retreating into the far distance as she was abruptly spotlit and under microscopic scrutiny.

Questions rolled into her brain. Did she really think she was going to get away with what she’d done? She’d even known about the security cameras…and yet she hadn’t thought about that when she’d gone behind the pharmacist’s counter the night before.

Everything was going to change as the result of this. Her life, once a struggle, was going to become insupportable.

Destiny? No…stupidity.

How the hell could she have done this?

“I’ll resign,” she said roughly. “Effective tonight. I should never have done it…. I was worried about him, overwrought about Stephan, and I made a horrible judgment call. I’m deeply sorry.”

Neither Havers nor Catya said a thing, but they didn’t have to. It was all about trust, and she had violated theirs. As well as a shitload of patient safety regulations.

“I’ll clean out my locker. And leave immediately.”

THIRTY-THREE

Rehvenge didn’t get out to see his mother enough.

That was the thought that occurred to him as he pulled in front of the safe house he’d moved her into nearly a year ago. After the family mansion in Caldwell had been compromised by lessers, he’d gotten everyone out of that house and installed them at this Tudor mansion well south of town.

It had been the only thing good that had come of his sister’s abduction—well, that and the fact that Bella had found herself a male of worth in the Brother who’d rescued her. The thing was, with Rehv having taken his mother from the city when he had, she and her beloved doggen had escaped what the Lessening Society had done to the aristocracy over the summer.

Rehv parked the Bentley in front of the mansion, and before he got out of the car, the door to the house opened and his mother’s doggen stood in the light, huddled against the cold.

Rehv’s wingtips had slick soles, so he was very careful as he came around on the dusting of snow. “Is she okay?”

The doggen stared up at him, her eyes misting with tears. “It’s getting close to the time.”

Rehv came inside, closed the door, and refused to hear that. “Not possible.”

“I’m very sorry, sire.” The doggen took out a white handkerchief from the pocket of her gray uniform. “Very…sorry.”

“She’s not old enough.”

“Her life has been far longer than her years.”

The doggen knew well what had gone on in the house during the time Bella’s father had been with them. She had cleaned up broken glass and shattered china. Had bandaged and nursed.

“V

erily, I can’t bear for her to go,” the maid said. “I shall be lost without my mistress.”

Rehv put a numb hand on her shoulder and squeezed gently. “You don’t know for sure. She hasn’t been to see Havers. Let me go be with her, okay?”

When the doggen nodded, Rehv slowly took the stairs up to the second floor, passing family portraits in oil that he had moved from the old house.

At the top of the landing, he went down to the left and knocked on a set of doors. “Mahmen?”

“In here, my son.”

The response in the Old Language came from behind another door, and he backtracked and went into her dressing room, the familiar scent of Chanel No. 5 calming him.

“Where are you?” he said to the yards and yards of hanging clothes.

“I am in the back, my dearest son.”

As Rehv walked down the rows of blouses and skirts and dresses and ball gowns, he breathed deeply. His mother’s signature perfume was on all of the garments, which were hung by color and type, and the bottle it came from was on the ornate dressing table, among her makeup and lotions and powders.

He found her in front of the three-way full-length mirror. Ironing.

Which was beyond odd and made him take stock of her.

His mother was regal even in her rose-colored dressing gown, her white hair up on her perfectly proportioned head, her posture exquisite as she sat on a high stool, her massive pear-shaped diamond flashing on her hand. The ironing board she sat behind had a woven basket and a can of spray starch on one end and a pile of pressed handkerchiefs on the other. As he watched her, she was in midkerchief, the pale yellow square she was working on halved, the iron she wielded hissing as she swept it up and down.

“Mahmen, what are you doing?” Okay, obvious on one level, but his mother was the chatelaine. He couldn’t remember ever seeing her do housework or laundry or anything of the sort. One had doggen for those things.

Madalina looked up at him, her faded blue eyes tired, her smile more effort than honest joy. “These were my father’s. We found them when we were going through the boxes that had been brought over from the old house’s attic.”

The “old house” was the one they had lived in for almost a century in Caldwell.

“You could get your maid to do that for you.” He came over and kissed her soft cheek. “She would love to help you.”

“She said as much, yes.” After she put her hand on his face, his mother went back to what she was doing, folding the linen square again, picking up the can of starch, misting over the kerchief. “But this is something I must do.”

“May I sit?” he asked, nodding at the chair beside the mirror.

“Oh, of course, where are my manners.” The iron went down and she started to get off the stool. “And we must get you something to—”

He held up his hand. “No, Mahmen, I’ve just eaten.”

She bowed to him and rearranged herself on her perch. “I am grateful for this audience, as I know the busy nature of your—”

“I’m your son. How can you think I wouldn’t come to you?”

The pressed kerchief was placed on top of its orderly brethren, and the last one was taken from the basket.

The iron exhaled steam as she smoothed its hot underbelly over the white square. As she moved slowly, he looked into the mirror. Her shoulder blades were prominent under the silk robe, her spine showing clearly at the back of her neck.

When he refocused on her face, he saw a tear drop from her eye onto the kerchief.

Oh…dearest Virgin Scribe, he thought. I’m not ready.

Rehv plugged his cane into the floor and came over to kneel before her. Turning the stool toward him, he removed the iron from her hand and put it aside, ready to take her to Havers’s, prepared to pay for whatever medicine would buy her more time.

“Mahmen, what ails you?” He took one of her father’s pressed handkerchiefs and dabbed under her eyes. “Speak unto your born son the weight of your heart.”

The tears were without end, and he caught them one by one. She was lovely even in her age and her crying, a fallen Chosen who had lived a hard life and nonetheless remained full of grace.

When she finally spoke, her voice was thin. “I am dying.” She shook her head before he could speak. “No, let us be truthful with each other. My end has arrived.”

We’ll see about that, Rehv thought to himself.

“My father”—she touched the handkerchief Rehv had dried her tears with—“my father…it is odd that I think of him daily and nightly now, but I do. He was the Primale long ago, and he loved his children. His greatest joy was his blood, and though we were many, he had relationships with us all. These handkerchiefs? They were made out of his robes. Verily, the industry of sewing was of favor to me, and he knew this and he gave unto me some of his robes.”

She reached over with a bony hand and smoothed the stack she’d ironed. “When I left the Other Side, he made me take a few of them. I was in love with a Brother and certain my life would be fulfilled only if I were with him. Of course, then…”

Yeah, it was the then part of her days that had caused her such pain: Then she was raped by a symphath and fell pregnant with Rehvenge and was forced to give birth to a half-breed monstrosity that somehow she had taken to her breast and loved as any son would have wanted to be loved. And all the while as she was imprisoned by the symphath king, the Brother she’d loved had searched for her—only to die in the process of getting her back.

And those tragedies hadn’t been the end of it.

“After I had been…returned, my father called me unto his deathbed,” she continued. “Of all the Chosen, of all his mates and his children, he’d wanted to see me. But I wouldn’t go. I couldn’t bear…I was not the daughter he knew.” Her eyes met Rehv’s, a deep pleading in them. “I didn’t want him to know of me at all. I was befouled.”

Man, he knew that feeling, but his mahmen didn’t need the burden of that. She had no clue about the kind of shit he was dealing with, and she would never know, because it was self-evident that the main reason he was whoring himself out was so she wouldn’t endure the torture of having her son deported.

“When I refused the summons, the Directrix came unto me and said he was suffering. That he wouldn’t go unto the Fade until I came to him. That he would stay on the painful brink of death for an eternity unless I relieved him. The following evening, I went with a heavy heart.” Now his mother’s stare grew fierce. “Upon my arrival at the Primale temple, he wanted to hold me, but I couldn’t…let him. I was a stranger with a beloved face, that was all, and I tried to speak of polite and distant things. It was then that he said something which afore now I could not fully understand. He said, ‘The heavy soul will not pass though the body is failing.’ He was imprisoned by what was unresolved with me. He felt as though he had failed in his role. That if he had kept me on the Other Side, my destiny would have been kinder than what had transpired after I left.”

Rehv’s throat got tight, a sudden, horrible suspicion parking in his brain’s front lot.

His mother’s voice was weak but forthright. “I approached the bed, and he reached for my hand, and I held his palm within mine own. I told him then that I loved my born son and that I was to be mated to a male of the glymera and that all was not lost. My father searched my face for the truth in the words I spoke, and when he was satisfied with what he saw, he closed his eyes…and drifted away. I knew that if I hadn’t come…” She took a deep breath. “Verily, I cannot leave this earth the way things are.”

Rehv shook his head. “Everyone’s fine, Mahmen. Bella and her young are well and safe. I’m—”

“Stop it.” His mother reached up and grabbed onto his chin, the way she had when he’d been very young and prone to causing trouble. “I know what you did. I know you killed my hellren, Rempoon.”

Rehv weighed whether it was better to keep up the lie, but given his mother’s expression, the truth was out, and nothing he could say

would dissuade her from it.

“How,” he said. “How did you find out?”

“Who else would have? Who else could have?” As she released her hold and stroked his cheek, he yearned to feel the warm touch. “Do not forget, I saw this face of yours each time my hellren lost his temper. My son, my strong, powerful son. Look at you.”

The honest, loving pride she had for him was something he’d never understood, given the circumstances of his conception.

“I also know,” she whispered, “that you killed your birth father. Twenty-five years ago.”

Now, that really got his attention. “You were not supposed to know. Any of this. Who told you about it?”

She took her hand from his face and pointed over to her makeup table, to a crystal bowl that he’d always assumed was for her manicures. “Old habits of a Chosen scribe, they die hard. I saw it in the water. Right after it happened.”

“And you kept it all to yourself,” he said with wonder.

“And could not any longer. Which was why I brought you here.”

That horrible feeling resurged, the result of his being trapped between what his mother was going to ask him to do and his strong conviction that his sister wasn’t going to benefit from knowing all her family’s dirty, evil secrets. Bella had stayed protected from this nastiness all her life, and there was no reason to do a full disclosure now, especially if their mother was dying.

Which Madalina wasn’t, he reminded himself.

“Mahmen—”

“Your sister must never be told.”

Rehv stiffened, praying he’d heard her right. “Excuse me?”

“Swear to me you shall do everything in your power to ensure that she never knows.” As his mother leaned forward and gripped his arms, he could tell she was really digging her fingers in by the way the bones in her hands and wrists stood out starkly. “I don’t want her to carry these burdens. You were forced to, and I would have spared you this if I could have, but I couldn’t. And if she doesn’t know, then the next generation will not have to suffer. Nalla will not bear the weight either. It can die with you and me. Swear to me.”