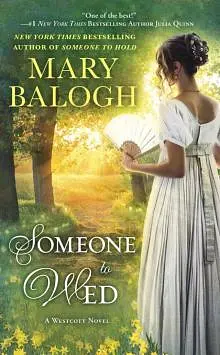

by Mary Balogh

Viola and Abigail were both smiling. Anna was teasing, Wren realized. She was also trying to take their minds off these first few minutes of their ordeal at being on display to the ton for the first time since their lives changed so catastrophically last year. Joel Cunningham, Camille’s husband, Wren had learned, had grown up at the orphanage in Bath with Anna and was her best friend. Wren remembered Viola telling her that she had decided to love Anna, though she could not yet feel that love. It was an idea to ponder.

The Duke of Netherby looked even more gorgeous than usual in satin and lace when most gentlemen, Alexander included, were wearing the more fashionable black and white. He was gazing outward across the theater with haughty languor through his quizzing glass. Candlelight glinted and winked off the jewels encrusted in its handle and about its rim and off those on his fingers and at his throat. He was a comforting presence as, she guessed, he fully intended to be this evening. So was Alexander, sitting slightly behind her, his hand beside hers on the velvet rail, their little fingers overlapping. Occasionally his finger stroked hers.

“When will the play begin?” she asked.

“It should be starting now,” Alexander told her. “But it is always a little late to allow for the arrival of stragglers. The stragglers know it, of course, and arrive even later than they otherwise would.”

“I believe the lateness of the start is also an acknowledgment of the fact that most people come to the theater to see everyone else as much as to watch the play, Alexander,” Viola said.

“Ah, such cynicism,” the duke said on a sigh. “Who was it who said the play’s the thing?”

“William Shakespeare,” Jessica said.

“. . . wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king,” Abigail added.

“Ah yes,” he said faintly.

Wren was watching a group of people step into the empty box across from theirs, two ladies and four gentlemen. Both ladies were blond and dressed all in sparkling white. They might well have been sisters. One of them seated herself off to one side of the box and one of the gentlemen went to sit beside and slightly behind her. The other lady took a seat in the middle of the box. She looked small and almost fragile amid a court of the other three gentlemen, who hovered about her, one of them positioning her chair, another taking her fan from her hand and plying it gently before her face, the third fetching something, presumably a footstool, from the back of the box and setting it at her feet. She smiled sweetly at them all and turned her attention outward to her court of admirers in the galleries and pit—or so it seemed to Wren, who was inclined at first to be amused.

But there was a strange feeling. A slight light-headedness. A suggestion of a buzzing in the ears. It could not be, of course. Twenty years had passed, and with those years some clarity of memory. But even if her memory had been crystal clear, time—twenty years of time—would have wrought significant changes. The lady raised one white-gloved hand in acknowledgment of the homage being paid her by a cluster of gentlemen in the pit and moved her head in a gracious nod. And there was something about both gestures . . .

“One does wonder how she does it,” Viola was saying, sounding amused.

“With a wig and cosmetics and an army of experts,” Jessica said. “When you see her close up, Aunt Viola, she looks quite grotesque.”

They might have been talking about anyone. And all talk ceased soon anyway, at least within their own box, as the candlelight dimmed and the play began. It was the first dramatic performance Wren had watched, and she marveled at the scenery, the costumes, the voices and gestures of the actors, the sense of gorgeous unreality that drew her into another world and made her almost forget her own. She would have been enthralled if she could have ignored the erratic fluttering of her heart.

It could not be.

One wonders how she does it.

With a wig and cosmetics and an army of experts.

And, just before silence had fallen in their box, Alexander’s voice—even her daughter is older than I am, perhaps older than Lizzie.

He might have been talking about anyone. She did not ask.

“Abigail, take my arm,” the Duke of Netherby said when the intermission began, “and we will stroll outside the box and perhaps even imbibe some lemonade, heaven help us. Jess, take my other arm so that I will be balanced.”

“Ought I?” Abigail asked.

“An unanswerable question,” he said, “and a thoroughly boring one.”

She took his arm after a glance at her mother and the three of them left the box.

“Shall we go too, Aunt Viola?” Anna suggested.

“Oh, whyever not?” Viola said, getting to her feet.

“Wren?” Alexander stood before her, one hand extended. “What is your wish? We can merely stretch our legs in here, if you choose.”

“Thank you.” She set her hand in his and stood. She did not turn her head, but with her peripheral vision she was aware that the two ladies in white had remained in their box and that other gentlemen had stepped into it, presumably to pay their respects.

“Are you enjoying the play?” Alexander asked, closing his hand about hers.

“Very much,” she said.

He moved his head a little closer and frowned slightly. “What is it?” he asked her. “Are you regretting your decision to come? Is this all a little overwhelming for you?”

“I am fine,” she said. But she was feeling the unfamiliar urge to step closer to him, to bury herself against him, to feel the safety of his arms about her. Perhaps that was all it was. Perhaps she was overwhelmed. Too much had happened too fast in her life.

He was still looking searchingly at her. But they were interrupted by the opening of the door and the appearance of the Radleys, Alexander’s aunt and uncle, who had come with a couple of friends to greet them. They stayed only a few minutes while Aunt Lilian told them how much she had enjoyed the wedding yesterday and the other couple congratulated them and Uncle Richard commented that they were putting Alexander to the blush.

And then they were alone again and Wren turned to resume her seat—and glanced unwillingly across at the box opposite. One lady and gentleman were still seated to the side. Most of the visiting gentlemen were leaving the box with bows for the other lady, while one member of her court had fetched her a glass of something and was presenting it to her with a graceful bow of his own. She was ignoring them all, however. She was holding a jeweled lorgnette to her eyes and looking directly across at their box. So were the other lady and the gentleman with her. Both sides of her face were visible, Wren realized. She sat down hastily and turned her attention toward the empty stage.

“You are attracting attention from over there,” Alexander said. “I hope it does not bother you. But really you ought to be feeling flattered, Wren. Lady Hodges usually notices no other lady but herself. By all accounts she has been the toast of the ton for at least the past thirty years, though her appearances in recent years are rarer and more carefully orchestrated.”

It could not be, Wren thought once more as the others returned to their box in time for the second half of the performance. It could not be.

But somehow it was.

Lady Hodges . . .

• • •

As far as Alexander was concerned, the evening had gone well. Cousin Viola was quietly dignified, rather as she had always been as far back as Alexander remembered. She nodded to a few people as they left the theater but did not exchange words or smiles with anyone. Abigail was both dignified and shyly smiling. Jessica was exuberant. Anna remarked upon the quality of the performance. Netherby was his usual imperturbable self. Wren spoke with admiration about the play and was warm in her thanks to Anna and Netherby as she hugged the former and shook hands with the latter before climbing into the carriage after Cousin Viola and Abigail.

“Well?” Alexander asked as the carriage moved away. “I

would say you all met the challenge quite magnificently. Are you pleased?” Wren had told him earlier of the agreement she and Cousin Viola had come to, though they had intended a mere sightseeing outing or two together.

“We did it, certainly,” Viola said. She had Abigail’s hand in hers, Alexander noticed. “We have proved something to ourselves and maybe to others too. Abby, was it an experiment to be repeated?”

“It was pleasant,” Abigail said, “and I do appreciate the effort Anastasia is making to draw us back into the family and even into society. I am sure tonight must have been her idea more than Avery’s.”

“Not Jessica’s?” her mother asked.

“No,” Abigail said. “Jessica wants to do quite the opposite, silly thing. She wants to withdraw from society herself in order to be with me. She does not understand that we must both find our place in the world but that those places will necessarily be very different.”

She was quite mature for one so young, Alexander thought. One did not always realize it. She was small and sweet and quiet and a bit fragile looking.

He moved slightly on the seat so that his shoulder was against Wren’s. She had fallen silent. Despite her praise for the play after it was finished, he had had the curious feeling during the second half that she was not really seeing it at all. He took her hand in his. She did not withdraw it, but it remained limp and unresponsive.

“No, Mama,” Abigail said. “I have no craving for more such evenings. Certainly not for parties. Not any longer. It was lovely to come for Alexander and Wren’s wedding and to see the family again. And it was wonderful beyond imagining to find Harry here.”

“Shall we go back home within the next few days, then?” Cousin Viola suggested. “And take Harry with us? He insists he will be well enough to return to the Peninsula within a week or two, but when he was sent home, he was ordered quite specifically by both an army surgeon and his commanding officer not to return for at least two months. We will fatten him up and perhaps take him to Bath to see Camille and Grandmama Kingsley and to meet Joel and Winifred and Sarah.”

“I should like that, Mama,” Abigail said. “I just have to persuade Jessica that really my world has not ended. Cam’s did not end, did it? It began last year.”

Alexander’s mother and Elizabeth were at home when they arrived, having just returned from a musical evening at the house of one of Elizabeth’s friends. They wanted to talk about it, and they wanted to hear about the visit to the theater. They all entered the drawing room together—except Wren, who slipped off upstairs without a word. And Harry had retired even before they left for the theater.

“Has Wren gone to bed?” Elizabeth asked five minutes or so later when she had not returned.

“I am not sure,” Alexander said. “I think perhaps she needed to be alone. The whole of the last week or so has been overwhelming for her, and this evening was perhaps too much.”

“Has she lived her whole life as a hermit?” Abigail asked. “And always veiled?”

“Yes,” Alexander said.

Abigail looked a bit surprised as her mother, Viola, said, “I am sorry, Alexander, if I have been the cause of distress to your wife. I challenged her to face the world with me. I like her exceedingly well, you know.”

“So do we all, Viola,” Alexander’s mother said. “But you must not blame yourself. We have learned Wren has a very firm mind of her own and will not be talked into anything she does not choose to do.”

Five minutes later Alexander was worried. He had expected her to come back down. Surely she would have said good night and offered some excuse of tiredness if she had not intended to do so.

“I will go up and see how she is,” he said.

She was not in bed—not in their bed, anyway. Nor was she in her dressing room or her own room. Or so he thought at first. There were no candles burning in there. Wherever was she, then? He set his candle down on the table beside the window and looked out, almost as though he expected to see her walking down the street. The room behind him was quiet, but there was a prickly feeling along his spine that warned him he was not alone. He turned.

She was on the floor on the far side of the bed, huddled into the corner, her knees drawn up to her chest, her forehead on her knees, one arm wrapped about her legs, the other about her head. She was not making a sound. He felt his stomach lurch and his knees turn a bit weak.

“Wren?” He spoke her name softly.

There was no response.

“Wren?” He moved closer to her and went down on his haunches before her. “What is it? What has happened?”

The only response this time was a slight tightening of both arms.

“Will you let me help you up from there?” he asked her. “Will you talk to me?”

She said something, but the words were muffled against her knees.

“I beg your pardon?” he said.

“Go away.” They were clear enough this time.

“But why?” he asked her.

No response.

He squeezed into the space beside her, sitting with his back against the wall, his wrists draped over his raised knees. There was not much room. His left side was pressed against her.

“I have let you down,” he said softly. “I promised you the life of your choosing, yet at every turn I have encouraged you to do what you are uncomfortable doing. You will say that I forced nothing on you, but my very willingness to allow you to decide each time you are called upon to move further and further into the open has been a form of coercion. For perhaps you have felt you need to prove something to me and to yourself. You do not need to prove anything, Wren. Had I been more forceful on a few occasions and said a firm no myself instead of leaving the decision to you, I might have saved you from this sort of . . . collapse. I ought to have said no to Netherby’s invitation today without even mentioning it at home. I will do better in the future, I promise you. Shall we go home to Brambledean? Tomorrow? There you may live as you wish to live, and I will be happy to see you happy. I care, Wren. I really do care.”

And he did, he realized. If he could have taken every last penny of her fortune at that moment and dumped it in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, he would have done it without any hesitation at all. He cared. For her. He cared deeply.

Still she said nothing. He eased his arm up from between them and wrapped it about her. She was as rigid as a statue.

“Wren,” he said. “Wren, my love, speak to me.”

She mumbled something.

“I beg your pardon?”

The words were quite distinct this time. “She is my mother.”

What? He did not say it aloud. But whom could she possibly mean? He frowned in thought. What had happened? Was it just the stress of too much exposure to other people—to strangers? Had she just reached a natural breaking point halfway through this evening? Halfway. There had been a difference between the two halves. She had been a bit tense from the start, but she had remained in command of herself, and he believed she had watched the play even if she had not been relaxed enough to be totally absorbed in it. There had been something troubling her during the interval, though she had denied it, and afterward she had been almost silent and . . . absent. She had disappeared upstairs without a word as soon as they came home.

She is my mother.

What the devil had happened? Snippets of the evening came back to him. He remembered then the two women in white who had been staring at Wren so pointedly. He remembered words, a few of them spoken by him.

One does wonder how she does it.

With a wig and cosmetics and an army of experts. When you see her close to . . . she looks quite grotesque.

Even her daughter is older than I am, perhaps older than Lizzie.

You are attracting attention from over there. I hope it does not bother you. But really you ought to be feeling flattered, Wren. Lady

Hodges usually notices no other lady but herself. By all accounts she has been the toast of the ton for at least the past thirty years, though her appearances in recent years are rarer and more carefully orchestrated.

Good God. Oh, good God!

“Lady Hodges?” he asked.

There was a low moan.

He turned as best he could in the confined space and wrapped his other arm about her too. It was not easy to do when she was curled up into a hard, unyielding ball. “Oh, good God,” he said aloud. “My poor darling. Let me hold you, Wren. Let me hold you properly. I am going to pick you up and carry you through to our room and hold you on the bed. Will you let me?”

She said nothing, but when he stood up and leaned down to scoop her into his arms, she released her tight hold on herself and let him get one arm beneath her knees and the other about her back beneath her shoulders. She let her head flop onto his shoulder, her eyes closed. He carried her through the two dressing rooms and set her on the bed, which had been turned down for the night. He eased off the light shoes she had worn to the theater and removed as many of her hairpins as he could find. And he lay down beside her and gathered her close. He did not try to talk to her. Sometimes, he thought, concern and love—yes, love—had to speak for themselves.

He did not know Lady Hodges, but he knew some things about her. Everyone did. She was a famous eccentric, if that was the right word to describe her. By all accounts she had been an extraordinarily beautiful girl, daughter of a gentleman of very moderate means. She had taken the ton by storm when her father had wangled an invitation from a distant relative to present her at a ton ball with his own daughter. Soon after, she married a wealthy baron. She had thereafter made her beauty the business of her life and had enslaved men by the dozens. It would not have been an entirely unusual story, had she not somehow contrived to hang on to her beauty—and her court—even after she had passed her youth and then her young womanhood and even her middle age. Young men were drawn by her wealth and strange fame, and she kept one of her daughters close so that—or so the accepted theory went—she might be flattered when told that they looked like sisters. Some particular flatterers even maintained that she looked like the younger sister. But Jessica had been right. Young and lovely as the woman appeared from a distance or in dim light, from close to she looked like a grotesque parody of youth. The woman’s vanity and self-absorption were commonly known to know no bounds.