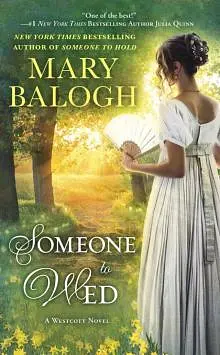

by Mary Balogh

“You were not annoyed with Jessica, then?” he asked as they crossed the road to make their way into the park.

“Oh, not at all,” she said, “despite my embarrassment. She was so very happy to make the announcement, as though I somehow belonged to her and she could bask in my reflected glory.”

He had been surprised yesterday at the way Jessica had taken to her and by the way she had responded in kind. It seemed nothing short of tragic that she had been so alone through much of her life, and he wondered if her aunt and uncle had been partly to blame, if perhaps they had coddled her rather too much when they might have nudged her out of the nest when she grew up. But he must not judge. He knew so few facts. He had heard Jessica say—with great delight—that Miss Heyden must be looked upon as a mystery woman when she appeared in public, her face shrouded by a veil. But she was a mystery woman even without it, for she wore layer upon layer of inner veils. He had had only brief, rare glimpses within, and this was one of them. Her eyes were bright and her right cheek was flushed, and she looked eager and youthful and approachable.

It did not last, of course. They passed a few people inside the park gates, and each time she raised her left hand to her bonnet brim, as though a brisk wind were attempting to blow it off. She did not draw down the veil, however, and she removed her hand whenever there was no one close by. He turned them onto a wide expanse of grass and led the way toward the line of trees beyond it. A path meandered through the trees close to the border of the park and was a lovely shaded place to stroll. It was not usually much frequented, most people preferring the more open areas of the park, where they might meet friends and acquaintances and have plenty of human activity to observe.

They talked about her long journey from Staffordshire, about the Serpentine and St. Paul’s Cathedral and Bond Street, about Hookham’s Library, which she had also visited this morning in order to borrow a few books on Elizabeth’s subscription. They talked about the House of Lords and some of the issues currently being debated there, about the wars and the weather. They passed only one other couple, and they were so intent upon what might have been a quarrel that they kept their heads down and their eyes lowered as they hurried past in a tense silence before resuming the argument just before they moved out of earshot.

“Why did you come?” Alexander asked at last. It was perhaps not a fair question, but it had been spoken aloud now.

There was a fairly lengthy silence, during which he became aware of the distant shrieking of children at play and birds trilling and chattering in the trees.

“When you and then Lady Overfield—Lizzie—asked me to come,” she said, “I saw it purely as an invitation I would not accept. But after I had gone to Staffordshire, I remembered it more as a challenge I had missed. And I asked myself if it really was a matter of courage. I have always wanted to come to London to see the famous sites. I like to think of myself as a strong, independent woman, and in many ways I am. I am proud of that. But sometimes I am aware of the coward lurking within. My veil is one aspect of it, I freely admit. My tendency to live the life of a hermit is another, though I genuinely like being alone and could never ever become truly gregarious. I came to prove that I could, Lord Riverdale. I did not come in answer to either your invitation or your sister’s. That would have been unfair, for I had refused both. However, I did intend calling at South Audley Street to pay my respects—oh, and to prove I was not too cowardly to do so.”

“It takes courage to call upon friends?” he asked her.

“I do not know,” she said. “Does it? I have never had friends. And are you a friend, Lord Riverdale? To me you were and are the gentleman to whom I once offered my fortune in exchange for marriage. I withdrew that offer when I understood that such a plan would not work for either of us. We could hardly be called friends, then, though I hope we are not enemies. We are something between the two, friendly acquaintances, perhaps. Your sister has been kind enough to call herself my friend since that day she visited me, but it was a friendship to be conducted largely at long distance by letter. Yes, it would have taken courage to call at Westcott House. And it seemed to me it might not be the right thing to do anyway. You came here to find a bride. I had no business interfering with that and still do not. But I met you here—quite by accident, I assure you—and then felt obliged to keep my promise to call upon Mrs. Westcott. Then, of course, I found myself being persuaded to stay there. I hope you do not believe I maneuvered such an outcome.”

“I know you did not,” he said. “I suggested it to my mother, and I am well acquainted with her powers of persuasion.”

“I hope I did not cause any awkwardness with the young lady you were escorting by the Serpentine,” she said. “She is very pretty. Though I am sure I could not have been mistaken for competition.”

“That pretty young lady’s mother has serious designs upon me,” he said, “as does her father. They will turn their matchmaking efforts upon someone else, however, as soon as they understand that I am not in the market for their daughter’s hand.”

“Ah,” she said, stopping and sliding her arm from his before moving off the path to look out through a gap in the trees to the sloping lawn beyond and the carriage drive below. “You have someone else in mind, then.”

“Yes,” he said.

She gazed into the distance, tall, elegant, self-contained, unapproachable again. “I hope for your mother’s sake,” she said, “oh, and for yours too, that she is someone who can do more than just repair your fortunes, Lord Riverdale. I hope you feel something for her and she for you.”

“Respect?” he said. “Liking? A hope of affection? Those three weigh more heavily with me than fortune. I could probably limp along somehow at Brambledean with only my own resources and the hard work and innovative ideas of my steward. The farms would not thrive for a number of years, and the house would have to continue to fall into disrepair except for absolute necessities. But I could see to it that body and soul were held together for my workers and their families, and perhaps they would forgive me for a lack of real prosperity if they were to see that I was in it with them, living and working alongside them. I would not marry for fortune alone.”

“No,” she said, still gazing off into the distance, her chin held high, her hands clasped at her waist, “you always did say that. It is something I respect about you.”

He was gazing at her rather than at the view, at her right profile, proud, inscrutable, beautiful. But appealing? Attractive? Lady of mystery. Jessica had chosen the very best words to describe her, he thought. She was unknown and perhaps unknowable. It had bothered him back at Brambledean, and it made him uneasy now. But . . . he had glimpsed something tantalizingly fleeting behind the veil. Something . . . No, he could not find the word. But something that invited him to keep looking.

She turned her head toward him at last. “I wish you well with your courtship,” she said. “Shall we walk onward? I am grateful that you brought me here. I like it better than the more public area by the water. There is something very soothing about a woodland path.”

And there was something about her eyes. Sadness? Yearning? “Miss Heyden,” he said, “will you marry me?”

Her eyes stilled on his. “Oh,” she said, but if she had intended to say more she was prevented by the inopportune approach of other people—three of them, one man and two ladies, trying to walk abreast on a path that was narrow even for two. Miss Heyden turned sharply back to gaze out at the park.

“Riverdale,” the man said affably.

“Matthews.” Alexander nodded genially. “A lovely day for a stroll, is it not?” He smiled at the ladies. Fortunately he did not know any of them well enough to feel obliged to hold them in conversation. They continued on their way after agreeing that yes, indeed, it was a beautiful day.

Alexander offered his arm to Miss Heyden again and took her a few steps farther off the path among the trees. “I will not

deny,” he said, “that your fortune would help serve my more pressing needs. You have seen Brambledean for yourself. But it is not your fortune alone that has prompted my offer. I beg you to believe me on that.”

“What has prompted you, then?” she asked without turning her head toward him. “Respect? Liking? A hope of affection? You cannot pretend to love me.”

“I will not pretend anything,” he said. “I try to be honest in all my dealings, but honesty with the woman I hope to marry is surely essential. No, I will not pretend to love you, Miss Heyden, if by love you mean the sort of grand passion that has produced some of our most memorable poetry and drama. But I believe I like you well enough to invite you to share my life. I would hope that liking would grow into affection. But respect is the strongest factor that has led me to speak today. I respect you as a businesswoman and as a person, though it is true I scarcely know you. I sense that you will be worth getting to know, however, and I hope you can feel the same about me. I hope you do not look at me and see only a mercenary man to whom things are more important than people. I beg your pardon. This is hardly the sort of speech a woman must hope to hear from the man who is proposing marriage to her. I have not dropped to one knee. I have not brought even one red rosebud with me.”

“No,” she said.

“No, it was not the sort of speech you hoped to hear?” he asked.

“No,” she said again. “I do not ask for roses or bended knee or the trappings of romance. They would be patently false and would arouse my distrust of everything else you have said. I know you would not marry me for my money alone. Liking and respect are perhaps a firm enough foundation upon which to base a marriage, and I both like and respect you. Thank you. I will tentatively agree to marry you.”

She was still gazing off into the distance, her eyes narrowed against the sunlight. He felt suddenly chilled. It was all very well to marry for practical reasons rather than for romantic ones. People did it all the time, and those marriages were often solid, even happy. He had resigned himself to the fact that he must do so too. But surely there ought to be more . . . warmth of feeling than this. He had just made her what was possibly the world’s worst ever proposal, and she had accepted, without looking at him and without conviction. Could he blame her?

“Tentatively?” he said.

“Your mother and your sister must give their unequivocal approval,” she said.

“It is I you would be marrying, Miss Heyden,” he said. “Our home would be Brambledean Court in Wiltshire. Theirs is Riddings Park in Kent. There is a goodly distance between the two.”

“You are a very close family, Lord Riverdale,” she said. “They love you dearly and want your happiness before all else. And you love them and do not wish to make them unhappy. Those are things not to be scoffed at. “

“You think they will disapprove, then?” he asked her. He expected that they would give their blessing, even if it came without any real joy. “Would your uncle and aunt disapprove if they were still alive? And would you refuse to marry me if they did?”

She thought about her answer. “I do not believe they would have disapproved,” she said.

“Even if they had known that I do not love you and you do not love me?” he asked her.

“They would see you as a good and honorable man,” she said. “They would want that for me. And they would trust my judgment even if they felt doubts.”

“Do you think my mother and Lizzie will not trust mine?” he asked.

“My aunt and uncle would have understood my motive as your family will understand yours,” she said. “They are very different motives, are they not? I want marriage, a husband and family, and you are a good choice, for you do have a sense of honor. I could feel confident that you would always treat me with courtesy and respect, that you would never abandon me or dishonor me. I could feel confident that you would be a good father to my children. You, on the other hand, want to be able to fulfill your obligations as Earl of Riverdale and master of Brambledean. You want a wife who can bring you sufficient funds to make that possible. And of course you want a wife who can bear you heirs. Our families would look from very different perspectives upon the prospect of our marrying.”

“Lizzie and my mother like you,” he said.

“Astonishingly, I believe they do,” she agreed. “But they may have reservations about my being your wife. I am not as other women are, Lord Riverdale—and I do not refer just to my birthmark. Were it not for my exposure to the glassworks, I would be a total recluse. I had a good upbringing and a good education, but all is theory and not practice with me. Just in the last couple of days, though I have mingled with no one except your mother and sister and cousin, I have seen and felt my differentness. I think of that young lady with whom you were walking here. Even in the brief glance I had of her, I was aware that in addition to her physical prettiness she was warm and charming and feminine and . . . vivacious.”

“I could have proposed marriage to Miss Littlewood anytime in the past three weeks,” he said. “She would have accepted—and I am not being conceited in believing so. I have not done it or felt the slightest wish to do so, though before I saw you again I did have the sinking feeling that soon I was going to have to choose someone not very different from her—someone whose father was rich and wanted a peer of the realm for a son-in-law. But then I did see you again and I knew, almost immediately, that I could feel comfortable with the thought of marrying you. And it is because you are so different from other women rather than despite that fact. I would rather marry you, Miss Heyden, than any other lady I have met, and I believe my mother would prefer it too. And Lizzie.”

“Then you must put it to the test,” she said, turning her head at last to look at him. “They must approve. I would not be responsible for putting any strain upon such a close family. It is worth more than anything else in the world and must be preserved at all costs.”

“And yet,” he said, “you left your own family at the age of ten and have not spoken of them since.” At least, that was one theory of what might have happened. It was equally possible that there had been some catastrophe that had wiped out all her family except her aunt.

For a moment her eyes held his. Then she jerked her hand free of his arm, turned about, and scrambled her way back to the path. She began to hurry along it, back in the direction from which they had come. He went after her. Damn him for a clumsy wretch.

“Miss Heyden.” He hurried up beside her and set a hand on her arm. She stopped but did not turn to face him.

“Sometimes,” she said, “it is the exception that proves the rule, Lord Riverdale. That is a cliché, but often there is truth to clichés.”

“I beg your pardon,” he said, moving around to face her and taking her gloved right hand in both of his. “I really am sorry to have upset you.” He raised her hand and held it to his lips. She was frowning, her eyes on their hands.

“I do not believe I can bring you any happiness, Lord Riverdale,” she said, and he found himself frowning back.

“Why not?” he asked. “Happiness does not come ready-made, you know. Even a sunset or a rose or a sonata or a book or a banquet is not happiness in itself. Each can cause happiness, but we have to allow feeling to interact with the moment. Surely if we like and respect each other, if we make an effort to live and work with each other, to make a home of our house and a family of any children with whom we may be blessed—surely then we can expect some happiness. We can even expect moments of vivid, conscious joy. But only if we want it and work for it and never allow ourselves to become complacent or imagine we are bored or inadequate. And only if we understand there is no such thing as happily-ever-after. Not for anyone, even those who fall wildly in love before marrying.”

She had raised her eyes to his, though she was still frowning. “If Mrs. Westcott objects,” she said, “I will fully understand. I will even agree with her. I would no

t want my son to marry me.”

“Good God,” he said, grinning suddenly. “I should hope not.”

She must have realized what she had just said. She snatched her hand from his grasp, pressed it to her mouth, gazed at him horrified for a moment, and then—exploded into laughter. And suddenly it all felt right. All of it. She was a real person despite the layers of armor, and she had a mind and a conscience and opinions. And even a sense of humor. There was substance to her character and a sturdy sort of honesty. And if being associated with her was going to be difficult, well, so it would with anyone. He glanced quickly ahead and behind. The path was deserted in both directions.

“We are—tentatively—betrothed, then, are we, Miss Heyden?” he asked.

She sobered instantly and lowered her hand. “Yes,” she said. “Tentatively.”

“Then we must celebrate,” he said, and cupped her face in his hands and ran the pads of his thumbs over her cheekbones while her hands came up to clasp his wrists.

“Someone might come,” she said.

“A very brief celebration,” he said, and kissed her—and instantly remembered the shock he had felt when he kissed her at Brambledean. He had felt an unexpected surge of desire then, and he felt it again now, inappropriate as it was when they were standing on a public path in the most public park in London. Her mouth was soft, her lips trembling slightly against his own. Her breath was warm on his cheek, her hands tight about his wrists. There was nothing remotely lascivious about the kiss, but . . . There was that knowledge that he could desire her.

She drew back her head rather sharply. “Are we mad?” she asked, her frown back. “We have forgotten the most important thing.”

“And that is . . . ?” He took a half step back from her.

“The very reason we put an end to everything on Easter Sunday,” she said. “I cannot be a countess, Lord Riverdale. I have no training or experience. I am a businesswoman, what the ton refers to with some disparagement as a cit. And when I am not that, I am a hermit. And I am—” She made a jerky gesture with her left hand in the direction of her cheek.