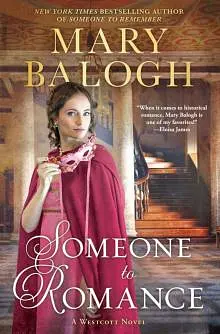

by Mary Balogh

Anna had spent twenty-two of her first twenty-five years at an orphanage in Bath, knowing herself only as Anna Snow, Snow being her mother’s maiden name, though she had not known that either. When she had discovered that she was Lady Anastasia Westcott, the legitimate daughter—and only legitimate child, as it happened—of the late Earl of Riverdale, it might have been expected that she would be bitter, that she would resent the family ties and the life of privilege all the other Westcotts shared. Instead she had loved them resolutely and fiercely almost from the first moment, even while some of them had resented her.

Jessica had hated her—she had come, seemingly from nowhere, to wreck Abby’s life as well as Camille’s and Harry’s, and to destroy her own dreams. It had taken her a long time to accept Anna as part of the Westcott family, then as Avery’s wife, her own sister-in-law and cousin. It had taken even longer to love her.

Avery’s eyes were resting upon Anna across the table. It often shocked Jessica to note that despite the almost bored expression her brother wore habitually in company, there was something in his eyes whenever he looked at his wife that spoke of fathomless depths of . . . Of what? Love? Passion? Passion seemed too strong a word to use of the indolent Avery, but appearances could be deceptive, Jessica thought. She was sure there must be a well of passion in him that very few people would suspect.

Oh, she thought with a sudden wave of unexpected yearning, how could she possibly be planning this year merely to settle for an eligible match? She wanted what Avery and Anna had. She wanted what Alexander and Wren had and Elizabeth and Colin. And Abby and Gil.

She wanted love. Even more than that, she wanted passion.

And she thought of that silly little detail that had kept her awake through most of the night, tossing and turning in her bed, punching and reshaping her pillow. She thought of Mr. Thorne’s little finger caressing hers upon the pianoforte keys, very lightly, very deliberately. Very briefly. How idiotic in the extreme that such a thing could have robbed her of a night’s sleep. If she were to tell anyone, she would be laughed off the face of the earth. She had felt that touch sizzle—yes, it was the only appropriate word—through her whole body, warming her cheeks, setting her heart to beating faster, creating a strange ache low in her abdomen and down along her inner thighs to her knees. Her toes had curled up inside her evening slippers.

She had wanted to weep.

She had asked him to romance her and had expected—if she had expected him to take up the challenge at all, though he had said he would—lavish gestures, similar to what she was getting from Mr. Rochford. Instead, in all the days since, she had had a pink rose each morning and a touch of his little finger to hers last evening.

It was laughable.

But she still, even after a few hours of sleep, felt like weeping.

She wanted . . .

Oh, she wanted and wanted and wanted.

What Avery had.

What Alexander had.

What Elizabeth and Camille and Abby had. And Aunt Matilda.

She wanted.

“Mr. Rochford has asked to take you rowing on the Thames this afternoon during the garden party?” her mother asked, speaking softly so as not to wake the baby.

“Yes,” Jessica said. “I promised that I would go out in one of the boats with him.”

“It is going to be a lovely day,” Anna said. “It already is.”

Jessica wished it were raining. She really did not like Mr. Rochford, she had decided last evening. He tried too hard to be charming and deferential. He smiled too much. All of which she might have ignored or at least excused on the grounds that he had not been to London before and was new to the position of prominence with the ton into which his prospects had thrown him even though his father was not yet officially the Earl of Lyndale. What had turned the tide against him last evening was the story he had told about the supposedly dead earl, his cousin. It might be perfectly true. She had no reason to believe it was not. But it included serious charges, involving even debauchery and murder. Ought he to have volunteered that information to a group of strangers in the middle of a party? About his own family? He had shown poor taste at best. At worst, he had been deliberately smearing the name of his father’s predecessor in order to make himself and his father look better by contrast. More legitimate, perhaps. How unnecessary. The law itself was about to make them legitimate.

Would she have been so offended if his dead cousin had not happened to have the same name as Mr. Thorne?

Gabriel?

Yes, of course she would. She did not like to hear people blackening the reputation of someone who was incapable of defending himself—or herself. Especially that of a relative. She could not imagine any of the Westcotts doing such a thing.

“You are right,” she said in answer to Anna’s comment. “It is not even windy. It is going to be a perfect day for a garden party.”

* * *

* * *

After a few hours spent at the House of Lords, Avery Archer, Duke of Netherby, and Alexander Westcott, Earl of Riverdale, had a late luncheon together at White’s Club.

They were not natural friends. At one time Alexander had viewed Avery as little more than an indolent fop, while Avery had considered Alexander a bit of a straitlaced bore. But that was before Harry was stripped of the earldom and his title and entailed properties passed to Alexander, a mere second cousin. It was before Avery married Lady Anastasia Westcott, the late earl’s newly discovered and very legitimate daughter. The crisis, or rather the series of crises that arose from those events and subsequent ones, had thrown the two men together on a number of occasions, not the least of which was a duel at which Avery fought—and won—and Alexander acted as his second. Their encounters had given them at first a grudging respect for each other and finally a cautious sort of friendship.

They spoke of House business and politics and world affairs in general while they ate. Once Avery discouraged a mutual acquaintance from joining them by raising his quizzing glass halfway to his eye, bidding the man a courteous but rather distant good day, and pointedly not asking for his company.

After their coffee had been served, Avery changed the subject.

“To what do I owe this very kind invitation?” he asked.

Alexander leaned back in his chair and set his linen napkin beside his saucer. “Jessica is giving serious consideration to settling down at last, is she?” he asked.

Avery raised his eyebrows. “If she is,” he said, “she has not confided in me. Nor would I encourage her to do so. That is a matter for my stepmother to worry her head over. Or not. My sister is of age and has been for several years.”

“What do you think of Rochford as a suitor for her hand?” Alexander asked.

“Do I have to think anything?” Avery sounded pained. “But it seems I must. You invited me to have luncheon with you for this exact purpose, I suppose.” Avery sighed, and then continued. “He is perfectly eligible and will be more so very soon unless the missing earl should suddenly drop down from the heavens into our midst at the last possible moment like a bad melodrama. Rochford has obviously set his sights upon Jessica. Equally obviously, the usual family committee has decided to promote the match and throw them together at every turn. Why else would he have been invited to your sister’s supposedly exclusive party last evening? I understand Jessica is to go out with him in a boat small enough to allow for only one rower and one passenger at a garden party this afternoon. One would hope his manners are polished enough that he will volunteer to be the rower.”

“Do you like him?” Alexander was frowning.

“I do not have to,” Avery said as he stirred his coffee. “Jessica would be the one marrying him. But as far as I am concerned, the man has too many teeth, and he displays them far too often. He also has abysmal taste in waistcoats. But he may have myriad other virtues to atone for those vices. And I would

not be called upon to look upon either the teeth or his waistcoats with any great frequency if Jess were to marry him. Do I assume you do not like him? On the slight acquaintance of one evening spent in his company?”

“What do you know of Gabriel Rochford?” Alexander asked. “The missing earl.”

“Nothing,” Avery said after taking a drink and setting his cup back in its saucer. “Except that he is missing and that he shares an angelic first name with Thorne. But the world, I must believe, contains a fair smattering of other Gabriels.”

“How long has the earl been missing?” Alexander asked. “Do you know?”

“I do not,” Avery said. “Is the question relevant to anything?”

“Rochford told a story last evening,” Alexander said. “Jessica heard it. So did Elizabeth and a few other guests. Estelle was part of the group. So was young Peter. It was not a suitable story for such an audience and such an occasion. Both Elizabeth and I turned the conversation to other topics as soon as we could, but we could hardly interrupt him midsentence. Of course, if you had been there with your quizzing glass and your ducal stare, he would have been muzzled far sooner.”

“Dear me,” Avery muttered.

“He told a story of his cousin’s wild ways,” Alexander said, “culminating in what he hinted was the rape of a neighbor’s daughter and the murder of her brother. After which he fled to escape the hangman’s noose.”

“Who would not, given the opportunity?” Avery said. “And all this was recounted in my sister’s hearing? And in your sister’s? Perhaps there will now be more to my distaste for the man than his teeth and his waistcoats.”

“As head of the Westcott family,” Alexander said, “it concerns me that Jessica may be considering marriage to a man of . . . shall we say questionable good taste? Perhaps even spite, since the missing earl was not present to speak for himself. Of course, she is also a member of the Archer family, of which you are the head.”

“You are begging me to exert myself, I understand, while assuring me that you will exert yourself,” Avery said. “How very tedious life becomes at times. Is it known how long ago the alleged rape and murder happened?”

“No,” Alexander said. “But it should be easy enough to find out. It should be possible also to discover how long Gabriel Thorne was in America before returning recently for a reason so vaguely explained that really it is no explanation at all.”

“You have been busy for a man who returned to London only a couple of days ago,” Avery said. He nodded to a waiter, who refilled his cup.

Alexander made a face at his own cup, with its cold coffee, and the waiter replaced it. “I probably have a foolishly suspicious mind,” he said. “That is what Wren told me last night anyway. She pointed out that Rochford is an extraordinarily handsome man—her words. She also added, however, that if he were applying for employment at her glassmaking works, she would reject him even before studying his credentials. Any man who smiles so much, she said, must be assumed to have a shallow, even devious, mind.”

“I must be careful not to smile overmuch in the presence of the Countess of Riverdale,” Avery said with a shudder.

Alexander laughed. “I cannot imagine,” he said, “that Wren would ever accuse you of having a shallow mind, Netherby. Or of smiling too much. She admires you greatly. But what of Thorne? If he is not making a play for Jessica too, I will eat my hat.”

“Not the gray beaver,” Avery said, looking pained again. “It sounds like a recipe for indigestion.”

“What do you know of him?” Alexander asked.

“Next to nothing,” Avery told him. “Little more, in fact, than I know of the missing earl. He has good taste in horses and curricles. He is of that rare breed of mortal that can produce exquisite music from a pianoforte without any formal training at all, or even any informal training, if Jessica is to be believed. He favors single-flower tributes to ladies he admires rather than bouquets so large it apparently takes two of my footmen to convey them to the drawing room. I believe, before you can demand an answer of me, that I must like him. Though being asked to express any sort of affection for someone outside my own family circle has a tendency to bore me.”

“Ah,” Alexander said. “But if Thorne has his way, Netherby, he will be a part of your inner family circle, will he not? And a Westcott by marriage.”

“But not yet,” Avery said softly. “Drink your coffee, Riverdale. You have already allowed one cup to develop a disgusting gray film.”

Alexander picked up his cup and drank. “There is one detail, I must confess,” he said, “that would appear to throw cold water on my suspicions. Rochford knew his cousin, the missing earl. Yet he showed no recognition of the man who admitted to having the same first name as the earl.”

“Ah,” Avery said. “But have we established that Rochford is a truthful man?”

Eleven

Lady Vickers had gladly accepted Gabriel’s offer to escort her to a garden party in Richmond that she wished to attend and to which he had also been invited.

“The house overlooks the river,” she explained to him in the carriage, “and the garden is glorious. Far more so than the interior of the house itself, which I always find surprisingly gloomy. One would think that whoever designed it would have thought to insist upon large windows facing the river, would one not? And that the occupants would not have chosen to cover what windows there are with gauzy curtains to preserve their privacy? Privacy from what, pray? The ducks? The hothouses alone are worth every mile of the tedious drive, however. You must not miss them, Gabriel. Or the rose arbor, which is built on three tiers. If you like rowing, there are several boats. And the food is always plentiful and delicious. The lobster patties are as good as any I have tasted anywhere.”

“You have persuaded me that I will enjoy myself,” he told her. “But I would be delighted to escort you, ma’am, even if the garden were a scrubby piece of faded grass abutting on a marsh, with only stale cake and weak tea for refreshments.”

“Oh, you shameless charmer,” she said, laughing as she slapped his arm.

He did not see much of her once they arrived. She introduced him to their hostess and a few other people, some of whom he had met before, and was then borne away by a couple of older ladies to join friends who had found seats in the shelter of a large oak tree down by the river.

“You will not wish to sit with a group of old ladies, Gabriel,” Lady Vickers informed him. “Stay here and enjoy yourself.”

He bowed to her and winked when the other two ladies had turned away.

Over the next half hour he was drawn into a few groups of fellow guests up on the terrace, most notably one that included a mother and her three young daughters, one of whom had her betrothed with her, a thin and chinless young man who looked as though his neckcloth had been tied too tightly. The other two simpered and giggled and blushed and had no conversation whatsoever beyond monosyllabic answers to any questions he posed them.

Gabriel found himself smiling at them in fond understanding while he conversed with their mother and the fiancé. He noticed that avuncular feeling coming over him again. Was he seriously considered husband material for girls who were only just beginning to leave their childhood behind? All upon the strength of an undisclosed American past and an unconfirmed fortune—and the fact that he was Sir Trevor Vickers’s godson?

Lady Estelle Lamarr, strolling past on the lawn below with her brother, must have assessed the situation at one glance. “Mr. Thorne,” she called, beckoning with the hand that was not holding a parasol over her head, “do come walking with us. We are going to look at the boats to decide if they are safe to ride in.”

“You are going to decide, Stell,” Bertrand Lamarr said as Gabriel approached them. “You are the one who is so afraid of water it is a wonder you ever even wash your face.”

Lady Estelle linked her arm through Gabriel’s. “Th

e trouble with having a twin brother, Mr. Thorne,” she said, “is that he will blurt out one’s deepest, most mortifying secrets to the very people one is most trying to impress.”

“You are trying to impress me?” Gabriel asked.

“But of course,” she said. “I am intended for you, am I not, by all the aunts and cousins from my adopted family? Oh, you need not look so aghast, Bertrand. Mr. Thorne and I had a frank chat about the whole thing last evening and understand each other perfectly.”

Her brother and Gabriel exchanged grins over her head.

“I did not initiate that conversation, I would hasten to add,” Gabriel told him.

“Of course you did not,” Lady Estelle said. “You are too much the gentleman. But everyone with eyes in his head—or hers—ought to have been able to see last night that it is Jessica and you, Mr. Thorne, not me and you.”

“Stell!” her brother scolded. “You will be putting Mr. Thorne to the blush, and all because he and Jessica played a duet together on the pianoforte last evening that ended in disaster and laughter. And—to change the subject—you see? I count five boats, and none of them have capsized. None of them are sinking or rocking out of control. No one in them looks anywhere close to panicking.”

“But how do we know,” she said, “that there are not supposed to be six boats out there? Where, oh where is the sixth?”

Gabriel laughed.

And rowing one of those five boats, he saw, was Anthony Rochford. Sitting facing him, her posture graceful and relaxed, was Lady Jessica Archer, the picture of summer beauty in a flimsy-looking dress of primrose yellow with a matching parasol that was raised over a straw bonnet. She was smiling and saying something. Rochford—it hardly needed stating—was smiling back with dazzling intensity.

Lady Estelle had seen them too. “Do you think, Mr. Thorne,” she asked, “that the missing earl is really dead? Or has he remained in hiding because he fears the consequences of making himself known?”