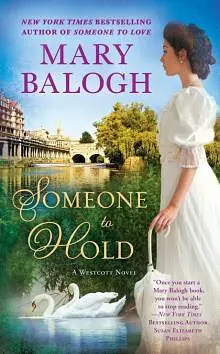

by Mary Balogh

And so his thoughts chased one another about in his head.

On Wednesday morning, not in the finest of moods, he took himself off with firm step and gritted teeth to a tailor and a bootmaker and a haberdasher.

Twenty

Camille half expected to see Joel on Monday while telling herself she did not expect him at all. She more than half expected him on Tuesday after her attention was drawn to the death notice in the morning paper. It was also the day of the funeral, she knew. He did not come, even though Miss Ford told her she had been to call upon him and that she had seen the Duke and Duchess of Netherby’s carriage approaching the house as she left. Miss Ford also told her that she had canceled school for the rest of the week so that Camille could spend time with her family during their brief visit to Bath.

He would not need to come on Wednesday, then, with the school closed. And, indeed, he did not come. Camille tried to tell herself that she was not disappointed. She tried, in fact, not to think of disappointment as a possibility. Why should he have come at any time during those three days, after all? Just because she had invited him to take her to bed and he had obliged her?

Ah, but it had not felt as sordid as that at the time. And at the time—or, at least, between times—they had talked and laughed and even been silly and had behaved like the best of friends.

Oh, she knew nothing! He did not come.

She was busy during those days. She taught on Monday and Tuesday. The main focus of attention was the knitted blanket, which had fired the children’s imaginations. Some of the girls wanted to learn to crochet so that they could help weave the squares together eventually and make a pretty border about the finished product. A few wanted to learn to embroider so that they could implement the idea one of the boys had to stitch the name of each knitter across the relevant square. A few of the boys dashed away to measure the babies’ cots and work out the size of each square and how many they would need to knit in order to make a blanket of the right size. Another of the boys made a design for the blanket, using the four colors of wool they were working with. During their knitting sessions the children took turns reading stories to the others.

Camille played with Sarah as often as she was able and gave some attention to Winifred, having realized that that was what the girl craved. She walked to the Royal York Hotel on Monday afternoon, having received a note from Aunt Louise to inform her that her grandmother and Aunt Matilda had arrived. She went to a reception her maternal grandmother gave Tuesday evening and surprised herself by almost enjoying it. It felt treacherously like old times to mingle and make polite conversation with Grandmama’s carefully selected guests.

Her mother took her aside late in the evening, and they sat together on a love seat while her mother told her she was going to return to Hinsford.

“To live?” Camille frowned.

“Yes,” her mother said. “Anastasia has begged me to do so, and in that clever, tactful way she has, she has made it appear that I will be doing her a favor by going. She will never live there herself now that she is married to Avery, yet she hates to see it empty and to know how its emptiness affects the morale of the people who work there and the social spirit of the neighborhood. Our neighbors and friends have spoken kindly of us to her, and . . . Well, Camille, she has willed Hinsford Manor to Harry after her time and has pointed out that if I go there to live, I will be keeping it lived in for my own family. I told her I would think about it, but really it has not taken a great deal of thought. I am going home.”

Camille felt a bit like weeping, but she found herself reverting to the old Camille, stiff and reserved and showing nothing of her feelings.

“Abigail is coming with me,” her mother continued. “She needs me and she needs her home. We will go there and . . . see what happens. Nothing will be the same, of course, and it may not be easy to be living the old life, when the old life cannot be fully recaptured. We will be Miss Kingsley and Miss Abigail Westcott instead of the Countess of Riverdale and Lady Abigail. But . . . Well . . .” She shrugged and smiled ruefully. “Will you come too, Camille? Or do you prefer your life here?”

Home. Camille felt suddenly awash in nostalgia. And temptation. But, as her mother had just said, there was no real going back.

“I do not know, Mama,” she said. “I will have to think about it.”

And she dropped, like a rock in a pond, into the murky depths of depression. She was living in a dreary little room in a building where she did not belong. She was teaching from instinct alone with very little idea of what she was doing or plan for how she would proceed in the weeks and months—and years?—ahead. She was in love with a man whose absence in the last couple of days suggested that she meant nothing to him apart from a casual lover, and a man who would almost inevitably move on to a new life of his own now that he was wealthy. She adored a baby who was not her own. She had cut herself off quite deliberately from everyone who would love her if she gave them the chance because she did not know who she was and did not want to be smothered by a protective love that would prevent her from finding out. The future yawned ahead with frightening emptiness and uncertainty. And she hated herself. She hated the fact that she could no longer hold herself together as she had done all her life, not realizing that what she held together was an empty core of nothing. She hated her own self-pity. She hated the fact that she was abjectly in love with a man who had made love to her three separate times just two days ago and had made no attempt to see her since. She hated . . .

“I will have to think about it,” she said again when she realized her mother’s eyes were fixed upon her. “But I am glad you and Abby are going home, Mama. And I am glad for Harry. Do you hate her?”

“Anastasia?” Her mother shook her head slowly. “No, I do not, Camille. She is your sister, and as I told her this morning, your father left behind something of far greater value than a large fortune. He sired four fine children.”

“Four.” Camille drew a slow breath. “How can you be so forgiving?”

“Because the alternative will only harm me,” her mother told her.

Cousin Althea and Mrs. Dance came to join them at that moment and they said no more on the subject.

On Wednesday morning, Camille joined her family for breakfast at the hotel. They did not linger over the meal, as several of their number were to make an excursion to Bathampton a few miles away, where they would enjoy a late luncheon before returning. Camille stayed to wave the three carriages on their way and then turned to Anastasia, who was standing out on the pavement too, listening to something Avery was saying to her.

“Anastasia,” Camille said before she could change her mind, “would you care to come and look in the shops along Milsom Street with me?”

Avery raised his eyebrows and pursed his lips. Anastasia looked at her with wide surprised eyes. “Oh, I would indeed, Camille,” she said. “Just give me a moment to fetch my bonnet and reticule.”

Avery looked steadily at Camille and then conversed for several minutes about the weather. “For the weather will always offer an endless supply of fascinating conversation,” he said, “especially when one is fortunate enough to live in England. Or unfortunate, as the case is more likely to be.”

The two ladies set off downhill toward Milsom Street, the most fashionable shopping street in Bath, a few minutes later. They walked side by side, talking about . . . the weather when they spoke at all. It was only as they turned onto Milsom Street that Camille changed the subject.

“Do you prefer to be called Anna rather than Anastasia?” she asked abruptly.

“Anna seems more like me,” Anastasia said. “I did not even know until a few months ago that it is not my full name. I prefer Anna, but I do not resent Anastasia. It is my name, after all.”

“I shall call you Anna from now on,” Camille said. “And, since it is less of a mouthful to call you sister rather than half sister, I sh

all do that too.”

Oh, this was difficult. This was very difficult. If her lips felt any stiffer, she would not be able to move them at all.

Anna turned her head and smiled at her. “Thank you, Camille,” she said. “You are very kind. I used to walk along this street occasionally for the pure pleasure of looking in the windows and dreaming of what I would buy if only I had limitless money. Once I saved for several months to buy a pair of black leather gloves that were so soft they felt more like fine velvet. I used to come and gaze at them every week. But—”

“Let me guess,” Camille said. “When you had finally saved enough and came to buy the gloves, they were gone.”

“Oh, they were still there,” Anna said. “I tried them on and they fit like . . . well, like a glove. I felt a few moments of glad triumph and utter joy—and then discovered that I could not justify such an extravagance. I left them on the counter with an unhappy shopgirl and went on my way.”

“Oh, but you had killed a dream,” Camille protested.

“I believe I had merely proved,” Anna said, “that having a dream and being on the journey to fulfilling it sometimes brings more happiness than actually achieving it. We have a habit, do we not, of thinking happiness is a future state if only this and that condition can be met? And so much of life passes us by without our realizing how happy we can be in this present moment, or how nearly happy. I had a good life as a girl and young adult despite what I was missing. And I had a dream.”

They had been gazing at bonnets in a window and had now moved on to a bookshop.

“Are you not happy now, then?” Camille asked.

“Oh, I am,” Anna assured her. “Happier than I have been my whole life. But it is not unalloyed happiness, Camille. Nothing is. This is human life in which there is no such thing as perfection. But I am happy. Today you have made me happier. It seems absurd, does it not, when all you have done is invite me to walk here with you and inform me that from today on you will call me Anna and sister? Camille, we are sisters. That is unbelievably precious to me.”

Camille felt guilty, for she could not say quite the same. She had been determined to reach out, though, to act as though Anna were her sister in the hope that in time she would also feel the truth of it.

“I have been very unhappy, Anna—for all the obvious reasons,” she said. “But in a strange way, that very fact is encouraging, for before all this happened I had dedicated my life to achieving perfection. I wanted to be the perfect lady above all else. Happiness meant nothing to me. Nor did love. They frightened me, for they suggested chaos and the impossibility of achieving perfection. Now that I have been desperately unhappy, I understand that I can be happy too and that I can love and be loved, and that unless I allow these things to happen to me, I will be only half alive. Oh, why are we gazing at books and talking about such strange things?”

“Because we are sisters,” Anna said. “This was always my very favorite shop in Bath. I did spend money here when I had some to spare. I have always loved books and the fact that I can read them and ponder them and keep them and see them and smell them—and reread them. What a treasure they are.”

“There is a coffee shop a little farther along the street,” Camille said. “Shall we go there?”

A few minutes later they were seated opposite each other at a small table, smelling the wonderful aroma of the two cups of coffee that had been set before them.

“Anna,” Camille said as she stirred in a spoonful of sugar, her eyes upon what she did. “I am happy about the baby. I shall enjoy being an aunt. There is a baby at the orphanage. She makes my heart ache. I believe I love all the children there, but there is something about her . . . Well.” She looked up. “I wish my father had confessed the truth after your mother’s passing. I wish he had married my mother properly after that and brought you into their home. I would have had an elder sister. I would not have been the eldest myself, and perhaps I would not have felt compelled to earn my father’s forgiveness for not being a son. I think I would have liked being a younger sister, and I think I might have enjoyed looking up to you. Perhaps not, though. Perhaps we would have squabbled incessantly.”

“I wish it too,” Anna said, “or that he had admitted the truth and acknowledged me and left me with my grandparents. I wish he had made another will. I wish he had married your mother properly so that Harry could have kept the earl’s title. I do not feel disloyal to Alex in saying so, for even he—perhaps especially he—wishes it were so. But it is not so, none of it, and we have to take life as it is. Camille—” She leaned forward across the table. “Do you love him? Does he love you?”

Camille stared at her. She knew Anna was not referring to Alexander. “Joel?” she said. And she heard a gurgle in her throat and felt her eyes grow hot and said what she doubted she would have said to another soul in the world, even Abby. “Yes. And no. Yes, I think I do, but no, he does not. We spent some time together on Sunday after Avery walked me home, and . . . I do not believe I have ever been happier. But I have not set eyes on him since. All sorts of momentous things are going on in his life, and lately he has been turning to me when he needs a friend in whom to confide, but I have not seen him since Sunday.”

It felt more horrible, more ominous put into words—not to mention abject.

“Then he must be in love,” Anna said. “I always knew he was an idiot. This proves it.”

There was no logic, no comfort in her words. Camille frowned, drew a deep breath, and turned her cup on its saucer without lifting it. She must get to the point of this contrived meeting. “I wanted to talk to you about something in particular,” she said.

Anna sat back in her chair.

“I am glad I have lived at the orphanage,” Camille said. “I am glad I have taught there. I have already learned a great deal—about you, about myself, about where I belong and do not belong. About being poor. I may well continue, for I have always been stubborn and do not give up a challenge easily. But there is an alternative, and I am at least considering it. My mother wants me to go home to Hinsford with her and Abigail. She will not press me, and I will not make a hasty decision. But . . .”

She looked up at last and met her sister’s eyes. It was going to be incredibly difficult to go on. But Alexander had advised her to allow herself to be loved. Avery had suggested something similar.

“Whether I go or stay,” she said, “will you—? Are you still willing to share the fortune you inherited from Papa?”

“Oh.” Anna expelled her breath on a long sigh. “You must know I am, Camille. If your mother has told you I will be leaving Hinsford to Harry, you must surely have guessed that I will also be leaving three-quarters of my fortune to my brother and sisters. It is not charity, Camille. It is not my attempt to buy your love. It is fair. We are all equally our father’s children.”

“Then I will take my share,” Camille said after drawing a ragged breath. “Not because I need it or necessarily intend to use it, but because—” She swallowed awkwardly. “Because you are offering it.”

Anna’s eyes filled with tears, and Camille could see that she was biting down on her upper lip. “Thank you.” Her lips mouthed the words, though very little sound came out. “It will be done immediately. Never mind the will. Wills can be changed. I shall write to Mr. Brumford. I wonder if Abigail . . . But it does not matter. Oh, I am so very happy.” She glanced downward. “And I would be even happier if we had not both allowed our coffee to grow cold.”

“Ugh,” Camille said, and they both laughed rather shakily.

It was not easy to allow oneself to be loved, Camille thought, to make oneself vulnerable. She really, really had not wanted to take the money—because her father had not left it, or anything else either, to her and she might never forgive him, though she remembered what her mother had said on that subject last night. But now the money was Anna’s, and sharing it with her sisters and brot

her was important to her. And accepting Anna with more than just her head had become necessary. She must somehow find a way of opening her heart too, but this was at least a start. If one could give love only by receiving it, then so be it.

And however was she to continue with her new life if she had riches in a bank account somewhere to tempt her? But perhaps she would go back home with Mama and Abby. There she would be far away from Joel. Oh, and the life would be familiar to her. She could give up the struggle . . .

Was she a coward after all, then?

“I suppose,” Anna said, frowning, “we could have these cups taken away and two fresh ones brought. They will think us strange, but what of that? I am a duchess, after all. And I have something to celebrate with one of my sisters.”

She raised an arm to summon the waitress, and they both laughed again.

* * *

Joel had never been inside the Upper Assembly Rooms, since they were largely the preserve of the upper classes. Afternoon teas there were open to anybody who had paid the subscription and, as in his case on that Thursday, to anyone who had been specifically invited. He donned the new coat he had bought yesterday, one that was readymade and therefore not quite as formfitting as an obsequious tailor assured him he would make the other two Joel had ordered. The tailor’s manner indicated to Joel that he had read the paper on Tuesday morning and had recognized the name of his new client. Joel was pleased with the coat anyway and decided that he would at least not disgrace himself when he walked into those hallowed and dreaded rooms. Now if only there had been a readymade pair of boots to fit him . . .