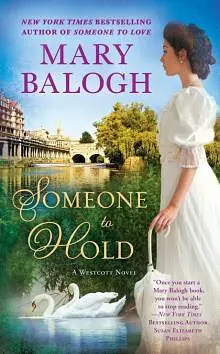

by Mary Balogh

Now Camille was sitting at one of the small pupils’ desks. The rest of the children had been dismissed for the day, but Caroline had been invited to stay and tell one of her own stories to her teacher, who had written it down word for word in large, bold print, leaving a blank space in the center of each of the four pages. Caroline, intrigued by the fact that it was her very own story, was reading it back to Camille, her finger identifying each word. And it seemed that she really was reading.

“You wrote went here, miss,” she said, looking up, “when really she ran.”

“My mistake,” Camille told her, though it had been a deliberate one. And Caroline had passed the test, as she did again with the other three deliberate errors.

“Excellent, Caroline,” Camille told her. “Now you can read your own story as well as other people’s when you want to. Can you guess what the spaces are for?”

The child shook her head.

“The most interesting books have pictures, do they not?” Camille said. “You can choose your favorite parts of your story and draw your own pictures.”

The little girl’s eyes lit up.

But the door opened at that moment, and Camille turned her head in some annoyance to see which child had come back to interrupt them and for what purpose. It was not a child, however. It was Joel Cunningham, who looked into the room, stepped inside when he saw she was there, and then came to an abrupt halt when he saw she was not alone.

“I beg your pardon,” he said. “Carry on.”

“You will miss your tea if I keep you here any longer,” she said to Caroline as she got to her feet. “Do you wish to take your story with you to read and illustrate? Or shall we keep it safe on a shelf here until tomorrow?”

Caroline wanted to take it to read to her doll. And she would draw the pictures while her doll watched. She gave Joel a wide, bright smile as he opened the door to let her out, her story clutched to her chest.

“I am trying to coax her to read,” Camille explained when he closed the door again. “She has been having some difficulty, and I have been trying out an idea.”

“It looks as if you may have had some success,” he said. “She seemed very eager to take that story with her. In my day we would have done anything on earth to avoid having to take schoolwork beyond this room.”

Camille was feeling horribly self-conscious. She had not seen him since Saturday, when she had gone dashing along rainy streets hand in hand with him, laughing for no reason except that she was enjoying herself—and ending up alone in his rooms with him. And if that was not shocking enough, she had allowed him to kiss her and—perhaps worse—she had asked him to hold her. She had been plagued by the memories ever since and had dreaded coming face-to-face with him again.

“What are you doing here?” she asked, clasping her hands tightly at her waist and straightening her shoulders. She could hear the severity in her voice.

“I came to see if you were still in the schoolroom,” he told her, running his fingers through his hair, a futile gesture since it was so short. There was something intense, almost wild, about his eyes, she noticed, and the way he was holding himself, as though there were a whole ball of energy coiled up inside him ready to burst loose.

“What is it?” she asked.

“I went to call on Cox-Phillips this morning,” he said. “He had nothing by way of work to offer me. He is eighty-five and at death’s door.”

“That is rather harsh.” Camille frowned.

“On the authority of his physician,” he said. “He expects to be dead within a week or two. He is setting his house in order, so to speak. His lawyer was going to see him this afternoon about his will.”

“I am sorry it was a wasted journey,” she said. “But why did he invite you up there if he did not wish to hire your services as a painter? Why did he not stop you from going if he suddenly found himself too ill to see you?”

“Oh, he saw me right enough,” he told her. “He even had his valet pull back the curtains so that he could have enough light for a closer look.” He laughed suddenly and Camille raised her eyebrows. “He was going to change his will this afternoon to cut out the three relatives who are expecting to inherit. I am guessing Viscount Uxbury is one of their number.”

“Oh,” she said. “He will not like that. But what does this have to do with you?”

“Not here.” He turned sharply away. “Come out with me.”

Where? She almost asked the question aloud. But it was obvious he was deeply disturbed about something and had turned to her of all people. She hesitated for only the merest moment.

“Wait here,” she said, “while I fetch my bonnet.”

Ten

Joel grasped Camille’s hand without conscious thought when they left the building and strode along the street with her. He had only one purpose in mind—to go home. It was only as they crossed the bridge that he wondered at last why he had turned to Camille Westcott of all people. Marvin Silver or Edgar Stephens would surely be home soon, and they were good friends as well as neighbors. Edwina was probably at her house. She was both friend and lover. And failing any of those three, why not Miss Ford?

But it was for the end of the school day and Camille he had waited as he paced the streets of Bath for what must have been hours. She would listen to him. She would understand. She knew what it was like to have one’s life turned upside down. And now he was taking her home with him, even after what had happened there the last time, was he? His pace slackened.

“I ought not to take you to my rooms,” he said. “Would you prefer that we keep walking?”

“No.” She was frowning. “Something has upset you. I will go home with you.”

“Thank you,” he said.

A few minutes later he was leaning against the closed door of his rooms while Camille hung up her bonnet and shawl. It seemed days rather than hours since he had left here this morning. She went ahead of him into the living room and turned to look at him, waiting for him to speak first.

He slumped onto one of the chairs without considering how ill-mannered he was being, set his elbows on his knees, and held his head in both hands.

“Cox-Phillips is my great-uncle,” he said. “It was his sister, my grandmother, who took me to the orphanage after her daughter, my mother, died giving birth to me. She was unmarried, of course—her name was Cunningham. My grandmother was extremely good to me. She paid handsomely for my keep until I was fifteen, and then, when she heard of my longing to go to art school, she paid my fees there. She loved me dearly too. She watched me from afar a number of times down the years and was so deeply affected each time that she suffered low spirits for days afterward.”

“Joel—” she said, but he could not stop now that he had started.

“She could not let me see her, of course,” he said. “She could not call at the orphanage and reveal herself to me. I might have climbed up onto the rooftop and yelled out the information for all of Bath to hear. Or someone might have seen her come and go and asked awkward questions. She could love me from afar and lavish money on me to show how much she cared, but she could not risk contamination by any personal contact. Something might have rubbed off on her and proved fatal to her health or her reputation. I was, after all, the bastard child of a fallen woman who just happened to be her daughter and apparently of an Italian artist of questionable talent who lived in Bath for long enough to turn the daughter’s head and get her with child before fleeing, lest he be forced into doing the honorable thing and marrying her and making me respectable.”

“Joel—” she said.

“Do you know what I was doing today between the time the carriage brought me back and the time I came to the schoolroom?” he asked, looking up at her. He did not wait for her to hazard a guess. “I wandered the streets, mentally squirming and clawing at myself as though to be rid of an itch. I felt—I feel as though I mus

t be covered with lice and fleas and bed bugs and other vermin. Or perhaps the contaminating dirt is all inside me and I can never be rid of it. That must be it, I think, for I will never be anything but a bastard to be shunned by all respectable folk, will I?”

Good God, where was all this coming from?

“Joel,” she said in her sergeant’s voice, “stop it. Right this minute.”

He looked blankly up at her and realized suddenly that he was sitting while she was still standing in the middle of the room. He leapt to his feet. “Yes, ma’am,” he said, and made her a mock salute. “I feel as though I am teetering on the edge of a vast universe and am about to tumble off into the endless blackness of empty space. And how is that for hyperbole, madam schoolmistress? I ought not to have brought you here. I ought not to have kept you standing while I have been sitting. You will think I am no gentleman and how very right you will be. And I ought not to be spouting all this pathetic nonsense into your ear. We scarcely know each other, after all. I assure you I am not usually this—”

“Joel,” she said. “Stop.”

And this time he did stop while she frowned at him and then took a few steps toward him. If he had not been fearing that at any moment he might faint, or fall off the edge of the universe, and if his teeth had not been chattering, he might have guessed her intent. But her hands were against his chest and then on his shoulders and then her arms were about his neck before he could do so, and by then it was too late not to take advantage of the comfort she offered. His arms went about her like iron bands and pressed her to him as though only by holding her could he keep himself upright and in one piece. He could feel the heat and the blessed life of her pressed to him from shoulders to knees. Her head was on his shoulder, her face turned in against his neck, her breath warm against his skin. He buried his face in her hair and felt almost safe.

Will you hold me, please? I need someone to hold me, she had said to him here on almost this very spot a few days ago. Now it was he making the same wordless plea.

Why exactly was he feeling so upset? He had always known that someone had handed him over to the orphanage, that whoever it was had chosen not to keep him, that in all probability that meant he was illegitimate, the unwanted product of an illicit union, something shameful that must be hidden away and denied for the rest of a lifetime. Yes, something—almost as though he were inanimate and therefore without real identity or feelings. A bastard. He had always known, but he had never given it a great deal of thought. It was just the way things were and would always be. There was no point in brooding about it. Having learned now, though, the name and identity of the woman who had abandoned him and her relationship to him—she had been his grandmother—and knowing how she had gazed on him in secret and been upset for days afterward without ever being upset enough to come and hug him, everything in him had erupted in pain. For now it was all real. And that man, his great-uncle, had insulted what little dignity he had, wanting to use him in order to wreak vengeance upon legitimate relatives who he believed had neglected him.

Joel knew all about neglect. He did not necessarily approve of vengeance, however, especially when he had been appointed as the avenging agent. Just like an inanimate thing again.

She used a sweet-smelling soap, something subtly but not overpoweringly floral. He could smell it in her hair. She was not slender, as her sister was and as Edwina was—and as Anna was. But her body was beautifully proportioned and voluptuously endowed. She was warm and nurturing and very feminine—despite the fact that on first acquaintance she had made him think of warrior Amazons, and despite the fact that she had just spoken to him in a voice of which an army sergeant might be proud.

They could not stand clasped thus together forever, he realized after a while, more was the pity. He sighed and moved his head as she raised her own, and they gazed at each other without speaking. She kept her femininity very well hidden most of the time, but her defenses were down at the moment. She was warm and yielding in his arms, and her eyes were smoky beneath slightly drooped eyelids.

He kissed her, openmouthed and needy, and tightened his hold on her again. He pressed his tongue to her closed lips and they parted to allow him to stroke the warm, moist flesh behind them. She shivered and opened her mouth and his tongue plunged into the heat within. He felt himself harden into the beginnings of arousal as his hands moved over her with a need that was somehow turning sexual. But . . . she was offering comfort because he was bewildered and suffering. How could be take advantage of that generosity of spirit? He could not, of course. Reluctantly he loosened his hold on her and took a step back.

“I am so sorry,” he said. “That was inappropriate. Forgive me, please. And I have not even invited you to sit down.”

“I am sorry too,” she said as she moved away from him to sit on the sofa. “I am sorry it has been so upsetting to you to have learned that your grandmother supported you but did not openly acknowledge you. It is the way the world works, though. It would have been stranger if she had made herself known to you. She had feelings for you despite everything, however, and she did do her best for you.”

“Much good her tender sensibilities did me,” he said. “And her best.”

“Well, they did.” She had herself firmly in hand again and looked like the stern, proper lady with whom he was more familiar. She sat with rigidly correct posture and a frown between her brows—she frowned rather often. “The orphanage is a good one. So, I assume, was the art school. You are a talented artist, but would you be doing as well as you are now if you had not gone there? She paid your fees. Could you have gone otherwise? Or would you have spent your life chopping meat at a butcher’s shop while your talent withered away undeveloped and unused? She could not show her affection openly. It is just not done in polite society for bastards to be openly acknowledged. And that is exactly what you are, Joel. Just as it is exactly what I am. Neither of us is to blame. It just is. Your grandmother did what she could regardless to see that you had all the necessities of life in a good home as you grew up and to help make your dream come true when you were old enough to leave.”

“All the necessities.” He stood with his hands at his back, looking down at her. He did not want to hear excuses for his grandmother. He wanted to feel angry and aggrieved, and he wanted someone to feel aggrieved for him. “Everything except love.”

“So, would you rather not know what you learned today?” she asked him, her expression stern. “Would you prefer to have gone through life not even sure that your name was rightfully your own? Do you wish you had not gone to that house today?”

He thought about it. “I suppose not,” he said grudgingly. “But what have I learned, Camille, beyond the very barest facts? My mother would never say who my father was. Cox-Phillips concluded he was the Italian painter solely on the evidence of my looks and the fact that I paint. I do not know anything about my mother and next to nothing about my grandmother. My great-uncle is the curmudgeon you said he used to be. I have no wish to know anything about his other three relatives, who are presumably mine too. And I do not imagine they would be delighted to know anything about their long-lost relative, an orphanage bastard, either.”

“Mr. Cox-Phillips invited you to call on him, then, just in order to tell you the truth about yourself before he dies?” she asked him.

He stared at her. Had he not told her? No, he supposed he had not. “He wanted to write me into his will this afternoon,” he said. “He wanted to leave me everything. Just to spite those other three. I said no, absolutely not. I was not going to have him use me in such a way.”

She stared back at him.

“I suppose I am glad to have learned something of my identity at last,” he said. “But my mother and grandmother are dead, and if my father is still living I have no way of tracing him. As for my mother’s uncle, he has apparently known for twenty-seven years where I am and has shown no interest in making himself known

to me. I have done very well without him and can continue to do so for a week or two longer until he dies.”

“Oh, Joel.” She sighed and relaxed into a woman again. She leaned back on the sofa. “You are hurting very badly. And you are trying to harden yourself against the pain and even deny it is there. You will feel a great deal better if you admit it.”

“And this is a pearl of wisdom from someone who knows?” he said.

Color flooded her cheeks and he was immediately contrite. Was he now going to lash out at the very person he had sought out for comfort? She had given it with unstinting generosity. “Yes, that is exactly right,” she said. “It feels a bit shameful to be suffering, does it not? As though one must have done something to deserve it. Or as if one were admitting to some weakness of character at being unable to shake off the hurt. But hiding it can turn one to marble with nothing but hollowness inside—and an unacknowledged pain. Do you believe Mr. Cox-Phillips was exaggerating when he told you he had only a week or two left to live?”

“No,” he said. “It was clearly what his physician had told him and what he believed. And he looks far from well. He is eighty-five years old and looks a hundred. He is tired of living. He has outlasted everyone who has ever meant anything to him and probably everything too.”

“Did he try to persuade you not to leave?” she asked. “Did he ask you to visit again?”

“No to both questions,” he said. “He invited me out there purely on a rather malicious whim, Camille. I refused to play a part in his game when he had probably expected that I would leap at the chance of inheriting whatever fortune he has. That was the end of the matter. There was no grand sentiment on either side when he told me who I was. He did not clasp me to his bosom as his long-lost grand-nephew. But then, I was never lost, was I? Only unclaimed, unwanted baggage. He made not the smallest pretense of feeling for me any of the sentiment he claimed his sister felt. Yes, it was a bit upsetting to learn the truth about myself so abruptly and unexpectedly and dispassionately. I cannot deny it. My head and every emotion were in a whirl after I had left him. I know I wandered the streets here for hours, though I would not be able to tell you exactly where I went. When I burst in upon you, I behaved like a madman and dragged you here when it was probably the last thing you wanted to do after a day of teaching. But you are wrong when you say I am still hurting. I am not, and I have you to thank for that. You have been kindness itself. I will not keep you any longer, though. I will walk you back home.”