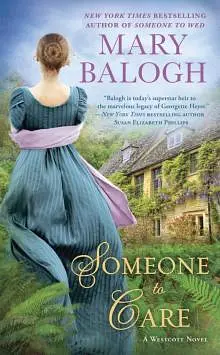

by Mary Balogh

She waited on that sunny morning until her grandmother and sister had gone out, as they often did, to the Pump Room down near Bath Abbey to join the promenade of the fashionable world. Not that the fashionable world was as impressive as it had once been in Bath’s heyday. A large number of the inhabitants now were seniors, who liked the quiet gentility of life here in stately surroundings. Even the visitors tended to be older people who came to take the waters and imagine, rightly or wrongly, that their health was the better for imposing such a foul-tasting ordeal upon themselves. Some even submerged themselves to the neck in it, though that was now considered a little extreme and old-fashioned.

Abigail liked going to the Pump Room, for at the age of eighteen she craved outings and company, and apparently her exquisite youthful beauty was much admired, though she did not receive many invitations to private parties or even to more public entertainments. She was not, after all, quite respectable despite the fact that Grandmama was eminently so. Camille had always steadfastly refused to accompany them anywhere they might meet other people in a social setting. On the rare occasions when she did step out, usually with Abby, she did so with stealth, a veil draped over the brim of her bonnet and pulled down over her face, for more than anything else she feared being recognized.

Not today, however. And, she vowed to herself, never again. She was done with the old life, and if anyone recognized her and chose to give her the cut direct, then she would give it right back. It was time for a new life and new acquaintances. And if there were a few bumps to traverse in moving from one world to the other, well, then, she would deal with them.

After Grandmama and Abby had left, she dressed in one of the more severe and conservative of her walking dresses, and donned a bonnet to match. She put on comfortable shoes, since the sort of dainty slippers she had always worn in the days when she traveled everywhere by carriage were useless now except to wear indoors. Finally taking up her gloves and reticule, she stepped out onto the cobbled street without waiting for a servant to open and hold the door for her and look askance at her lone state, perhaps even try to stop her or send a footman trailing after her. She stood outside for a few moments, assailed by a sudden terror bordering upon panic and wondering if perhaps after all she should scurry back inside to hide in darkness and safety. In her whole life she had rarely stepped beyond the confines of house or walled park unaccompanied by a family member or a servant, often both. But those days were over, even though Grandmama would doubtless argue the point. Camille squared her shoulders, lifted her chin, and strode off downhill in the general direction of Bath Abbey.

Her actual destination, however, was a house on Northumberland Place, near the Guildhall and the market and the Pulteney Bridge, which spanned the River Avon with grandiose elegance. It was a building indistinguishable from many of the other Georgian edifices with which the city abounded, solid yet pleasing to the eye and three stories high, not counting the basement and the attic, except that this one was actually three houses that had been made into one in order to accommodate an institution.

An orphanage, to be precise.

It was where Anna Snow, more recently Lady Anastasia Westcott, now the Duchess of Netherby, had spent her childhood. It was where she had taught for several years after she grew up. It was from there that she had been summoned to London by a solicitor’s letter. And it was in London that their paths and their histories had converged, Camille’s and Anastasia’s, the one to be elevated to heights beyond her wildest imaginings, the other to be plunged to depths lower than her worst nightmares.

Anastasia, also a daughter of the Earl of Riverdale, had been consigned to the orphanage—by him—at a very young age on the death of her mother. She had grown up there, supported financially but quite ignorant of who she was. She had not even known her real name. She had been Anna Snow, Snow being her mother’s maiden name—though she had not realized that either. Camille, on the other hand, born three years after Anastasia, had been brought up to a life of privilege and wealth and entitlement with Harry and Abigail, her younger siblings. None of them had known of Anastasia’s existence. Well, Mama had, but she had always assumed that the child Papa secretly supported at an orphanage in Bath was the love child of a mistress. It was only after his death several months ago that the truth came out.

And what a catastrophic truth it was!

Alice Snow, Anastasia’s mother, had been Papa’s legitimate wife. They had married secretly in Bath, though she had left him a year or so later when her health failed and returned to her parents’ home near Bristol, taking their child with her. She had died sometime later of consumption, but not until four months after Papa married Mama in a bigamous marriage that had no legality. And because the marriage was null and void, all issue of that marriage was illegitimate. Harry had lost the title he had so recently inherited, Mama had lost all social status and had reverted to her maiden name—she now called herself Miss Kingsley and lived with her clergyman brother, Uncle Michael, at a country vicarage in Dorsetshire. Camille and Abigail were no longer Lady Camille and Lady Abigail. Everything that had been theirs had been stripped away. Cousin Alexander Westcott—he was actually a second cousin—had inherited the title and entailed property despite the fact that he had genuinely not wanted either, and Anastasia had inherited everything else. That everything else was the vast fortune Papa had amassed after his bigamous marriage to Mama. It also included Hinsford Manor, the country home in Hampshire where they had always lived when they were not in London, and Westcott House, their London residence.

Camille, Harry, Abigail, and their mother had been left with nothing.

As a final crushing blow, Camille had lost her fiancé. Viscount Uxbury had called upon her the very day they heard the news. But instead of offering the expected sympathy and support, and instead of sweeping her off to the altar, a special license waving from one hand, he had suggested that she send a notice to the papers announcing the ending of their betrothal so that she would not have to suffer the added shame of being cast off. Yes, a crushing blow indeed, though Camille never spoke of it. Just when it had seemed there could not possibly be any lower to sink or greater pain to be borne, there could be and there was, but the pain at least was something she could keep to herself.

So here she and Abigail were, living in Bath of all places on the charity of their grandmother, while Mama languished in Dorsetshire and Harry was in Portugal or Spain as a junior officer with the 95th Foot Regiment, also known as the Rifles, fighting the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte. He could not have afforded the commission on his own, of course. Avery, Duke of Netherby, their stepcousin and Harry’s guardian, had purchased it for him. Harry, to his credit, had refused to allow Avery to set him up in a more prestigious, and far more costly, cavalry regiment and had made it clear that he would not allow Avery to purchase any promotions for him either.

By what sort of irony had she ended up in the very place where Anastasia had grown up, Camille wondered, not for the first time, as she descended the hill. The orphanage had acted like a magnet ever since she came here, drawing her much against her will. She had walked past it a couple of times with Abigail and had finally—over Abby’s protests—gone inside to introduce herself to the matron, Miss Ford, who had given her a tour of the institution while Abby remained outside without a chaperon. It had been both an ordeal and a relief, actually seeing the place, walking the floors Anastasia must have walked a thousand times and more. It was not the sort of horror of an institution one sometimes heard about. The building was spacious and clean. The adults who ran it looked well-groomed and cheerful. The children she saw were decently clad and nicely behaved and appeared to be well-fed. The majority of them, Miss Ford had explained, were adequately, even generously supported by a parent or family member even though most of those adults chose to remain anonymous. The others were supported by local benefactors.

One of those benefactors, Camille had been amazed to learn, tho

ugh not of any specific child, was her own grandmother. For some reason of her own, she had recently called there and agreed to equip the schoolroom with a large bookcase and books to fill it. Why she had felt the need to do so, Camille did not know, any more than she understood her own compulsion to see the building and actually step inside it. Grandmama could surely feel no more kindly disposed toward Anastasia than she, Camille, did. Less so, in fact. Anastasia was at least Camille’s half sister, perish the thought, but she was nothing to Grandmama apart from being the visible evidence of a marriage that had deprived her own daughter of the very identity that had apparently been hers for longer than twenty years. Goodness, Mama had been Viola Westcott, Countess of Riverdale, for all those years, though in fact the only one of those names to which she had had any legal claim was Viola.

Today Camille was going back to the orphanage alone. Anna Snow had been replaced by another teacher, but Miss Ford had mentioned in passing during that earlier visit that Miss Nunce might not remain there long. Camille had hinted with an impulsiveness that had both puzzled and alarmed her that she might be interested in filling the post herself, should the teacher resign. Perhaps Miss Ford had forgotten or not taken her seriously. Or perhaps she had judged Camille unsuited to the position. However it was, she had not informed Camille when Miss Nunce did indeed leave. It was quite by chance that Grandmama had seen the notice for a new teacher in yesterday’s paper and had read it aloud to her granddaughters.

What on earth, Camille asked herself as she neared the bottom of the hill and turned in the direction of Northumberland Place, did she know about teaching? Specifically, what did she know about teaching a supposedly large group of children of all ages and abilities and both genders? She frowned, and a young couple approaching her along the pavement stepped smartly out of her way as though a fearful presence were bearing down upon them. Camille did not even notice.

Why on earth was she going to beg to be allowed to teach orphans in the very place where Anastasia had grown up and taught? She still disliked, resented, and—yes—even hated the former Anna Snow. It did not matter that she knew she was being unfair—after all, it was not Anastasia’s fault that Papa had behaved so despicably, and she had suffered the consequences for twenty-five years before discovering the truth about herself. It did not matter either that Anastasia had attempted to embrace her newly discovered siblings as family and had offered more than once to share everything she had inherited with them and to allow her two half sisters to continue to live with their mama at Hinsford Manor, which now belonged to her. In fact, her generosity merely made it harder to like her. How dared she offer them a portion of what had always been theirs by right, as though she were doing them a great and gracious favor? Which in a sense she was.

It was a purely irrational hostility, of course, but raw emotions were not often reasonable. And Camille’s emotions were still as raw as open wounds that had not even begun to heal.

So why exactly was she coming here? She stood on the pavement outside the main doors of the orphanage for a couple of minutes, debating the question just as though she had not already done so all yesterday and through a night of fitful sleep and long wakeful periods. Was it just because she felt the need to do something with her life? But were there not other, more suitable things she could do instead? And if she must teach, were there not more respectable positions to which she might aspire? There were genteel girls’ schools in Bath, and there were always people in search of well-bred governesses for their daughters. But her need to come here today had nothing really to do with any desire to teach, did it? It was . . . Well, what was it?

The need to step into Anna Snow’s shoes to discover what they felt like? What an absolutely ghastly thought. But if she stood out here any longer, she would lose her courage and find herself trudging back uphill, lost and defeated and abject and every other horrid thing she could think of. Besides, standing here was decidedly uncomfortable. Though it was July and the sun was shining, it was still only morning and she was in the shade of the building. The street was acting as a type of funnel too for a brisk wind.

She stepped forward, lifted the heavy knocker away from the door, hesitated for only a moment, then let it fall. Perhaps she would be denied employment. What a huge relief that would be.

* * *

* * *

Joel Cunningham was feeling on top of the world when he got out of bed that morning. July sunshine poured into his rooms as soon as he pulled back the curtains from every window to let it in, filling them with light and warmth. But it was not just the perfect summer day that had lifted his mood. This morning he was taking the time to appreciate his home. His rooms—plural.

He had worked hard in the twelve years since he left the orphanage at the age of fifteen and taken up residence in one small room on the top floor of a house on Grove Street just west of the River Avon. He had taken employment at a butcher’s shop while also attending art school. The anonymous benefactor who had paid his way at the orphanage throughout his childhood had paid the school fees too and covered the cost of basic school supplies, though for everything else he had been on his own. He had persevered at both school and employment while working on his painting whenever he could.

Often after paying his rent he had had to make the choice between eating and buying extra supplies, and eating had not always won. But those days were behind him. He had been sitting outside the Pump Room in the abbey yard one afternoon a few years ago, sketching a vagabond perched alone on a nearby bench and sharing a crust of bread with the pigeons. Sketching people he saw about him on the streets was something Joel loved doing, and something for which one of his art teachers had told him he had a genuine talent. He had been unaware of a gentleman sitting down next to him until the man spoke. The result of the ensuing conversation had been a commission to paint a portrait of the man’s wife. Joel had been terrified of failing, but he had been pleased with the way the painting turned out. He had made no attempt to make the lady appear younger or lovelier than she was, but both husband and wife had seemed genuinely delighted with what they called the realism of the portrait. They had shown it to some friends and recommended him to others.

The result had been more such commissions and then still more, until he was often fairly swamped by demands for his services and wished there were more hours in the day. He had been able to leave his employment two years ago and raise his fees. Recently he had raised them again, but no one yet had complained that he was overcharging. It had been time to begin looking for a studio in which to work. But last month the family that occupied the rest of the top floor of the house in which he had his room had given notice, and Joel had asked the landlord if he could rent the whole floor, which came fully furnished. He would have the luxury of a sizable studio in which to work as well as a living room, a bedchamber, a kitchen that doubled as a dining room, and a washroom. It seemed to him a true palace.

The family having moved out the morning before, last night he had celebrated his change in fortune by inviting five friends, all male, to come and share the meat pies he had bought from the butcher’s shop, a cake from the bakery next to it, and a few bottles of wine. It had been a merry housewarming.

“You will be giving up the orphanage, I suppose,” Marvin Silver, the bank clerk who lived on the middle floor, had said after toasting Joel’s continued success.

“Teaching there, do you mean?” Joel had asked.

“You do not get paid, do you?” Marvin had said. “And it sounds as though you need all your time to keep up with what you are being paid for—quite handsomely, I have heard.”

Joel volunteered his time two afternoons a week at the orphanage school, teaching art to those who wanted to do a little more than was being offered in the art classes provided by the regular teacher. Actually, teach was somewhat of a misnomer for what he did with those children. He thought of his role to be more in the nature of inspiring them to discover and expres

s their individual artistic vision and talent. He used to look forward to those afternoons. They had not been so enjoyable lately, however, though that had nothing to do with the children or with his increasingly busy life beyond the orphanage walls.

“I’ll always find the time to go there,” he had assured Marvin, and one of the other fellows had slapped him with hearty good cheer on the back.

“And what of Mrs. Tull?” he had asked him, waggling his eyebrows. “Are you thinking of moving her in here to cook and clean for you among other things, Joel? As Mrs. Cunningham, perhaps? You can probably afford a wife.”

Edwina Tull was a pretty and amiable widow, about eight years Joel’s senior. She appeared to have been left comfortably well-off by her late husband, though in the three years Joel had known her he had come to suspect that she entertained other male friends apart from him and that she accepted gifts—monetary gifts—from them as she did from him. The fact that he was very possibly not her only male friend did not particularly bother him. Indeed, he was quite happy that there was never any suggestion of a commitment between them. She was respectable and affectionate and discreet, and she provided him with regular female companionship and lively conversation as well as good sex. He was satisfied with that. His heart, unfortunately, had long ago been given elsewhere, and he had not got it back yet even though the object of his devotion had recently married someone else.

“I am quite happy to enjoy my expanded living quarters alone for a while yet,” he had said. “Besides, I believe Mrs. Tull is quite happy with her independence.”