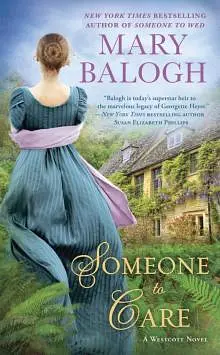

by Mary Balogh

It was after all impossible to tell the truth, though she had steeled herself throughout the journey home to do just that. For these were decent, much-loved, respectable people—her mother, well-known for most of her life in Bath society; her brother, a man of the cloth, and his wife; the Dowager Countess of Riverdale, her former mother-in-law, who at the age of seventy-one had made the effort to come all the way to Bath; her former sisters-in-law; Avery, Duke of Netherby, who had once been Harry’s guardian, and his duchess, Anna, who was Humphrey’s only legitimate child; Jessica, Avery’s half sister and Abigail’s dearest friend.

And her own daughters. And her grandchildren. Had they not all suffered enough in the past two years without . . . How had he phrased it? But it took no great effort of memory to remember. Had her children not suffered enough without having their mother known as a slut?

She hated him, she hated him, she hated him.

She believed she really did.

And she would not marry him. But now was not the time to announce that.

When would be the time, then?

Oh, she was being justly punished. She had no one to blame but herself for her own unhappiness. The trouble was that one sometimes dragged innocent people down into one’s own misery and guilt.

Marcel. She closed her eyes for a moment while the noise of conversation proceeded about her in Camille and Joel’s drawing room. Why had they had to be stranded at the same country inn? What were the chances?

Why did you stay instead of leaving with your brother?

Why did you speak to me?

Why did I reply?

She felt a shoulder pressed to her arm and opened her eyes to smile down at Winifred and set an arm about her thin shoulders.

“I finished A Pilgrim’s Progress, Grandmama,” she said. “It was very instructional. Are you proud of me? Will you help me choose my next book?”

* * *

• • •

While they were still at the cottage in Devonshire together, Estelle had asked Abigail for a list of all her family members and where they lived. Abigail and her mother were to come for the party, and Estelle’s father had told her that that would be quite sufficient to make the betrothal aspect of the party a grand occasion for their neighbors. Bertrand had agreed that it was all she could reasonably expect when the wedding itself was to follow in just a couple of months and involve everyone from both families in traveling all the way to Brambledean in Wiltshire. Aunt Jane had reminded her niece that this was the first party she had organized and was a remarkably ambitious undertaking even as it was.

“Anything on a grander scale would simply overwhelm you, my love,” she said, kindly enough. “You have no idea.”

Estelle dutifully took the guest list she had made for her father’s birthday party and added Miss Kingsley’s and Abigail Westcott’s names. She would have added her aunt Annemarie and uncle William Cornish, who lived a mere twenty miles away, if she had not noticed that, of course, their names were already there. If everyone came, as surely they would, they would be well over thirty in number. That included the thirteen people who were already living at the house, it was true, but even so, it was an impressive number for a country party in October. It was all very exciting.

But oh, it was not as exciting as it would be if only . . .

Having discovered her wings only very recently, Estelle was eager to spread them again to see if she could fly. She was very nearly a woman, even if she was not quite eighteen. She wanted . . . Well. Without any real expectation of success, she added Abigail’s list to her own and began the laborious task of writing the invitations. She refused all help, even though both Bertrand and Aunt Jane offered, and even Cousin Ellen, Aunt Jane’s daughter.

* * *

• • •

In Bath, Camille handed the invitation to Joel without any comment and watched his face as he read it.

“Unless memory is failing me,” he said, “we do not have any official booking here that week.”

“We do not,” she said.

“It would be a long journey for the children,” he said.

“And for us.” She smiled at him. “And you have only recently returned from another long journey, you poor thing.”

“Winifred would be thrilled,” he said.

“Yes,” she agreed. “So would Sarah. And Jacob would sleep.”

“Perhaps your Grandmama Kingsley would like to come with us,” he said. “I expect she has been invited too.”

“I remember the Marquess of Dorchester from the spring months I used to spend in London,” she said, “though he was plain Mr. Lamarr then. He is fearfully handsome.”

“Fearfully?”

“Yes,” she said. “Fearfully. I suppose you did not notice. I still find it hard to believe that Mama is going to marry him.”

“Or anyone?” he asked.

“I suppose so,” she said after thinking about it. “It is hard to imagine one’s mother wanting to marry anyone. We will go, then?”

“Of course,” he said.

And of course Mrs. Kingsley was happy to go with them. “I need to take a look at that young man,” she said. “I do not like the few things I have heard of him.”

In Dorsetshire, the Reverend Michael Kingsley conferred with his wife. He had just taken a far longer leave of absence than he had originally intended. They had gone to Bath supposedly for a few days to attend the christening of his great-nephew and had stayed for a few weeks after the disappearance of his sister. He would need to take leave again over Christmas—the very worst time, with the exception of Easter, for a man of his calling—in order to attend Viola’s wedding. He really could not make a good case for going all the way to Northamptonshire in October just to attend her betrothal party.

“Could I, Mary?” he asked.

“She is your only sister,” his wife reminded him. “When she came to live with you here for a while a couple of years ago, she was dreadfully hurt. She was all locked up inside herself, as I remember you telling me. And I agreed, though we were not married at the time and I did not see a great deal of her. You want to go, do you not? You want to see him. You are worried.”

“Riverdale—her husband—was the lowest form of human life,” he said, “and may I be forgiven for passing such judgment upon a fellow mortal. I could not abide being within ten miles of him. Consequently, and to my shame, I did not see much of Viola during those years, or of my nieces and nephew. I cannot bear the thought that she might be making the same mistake all over again, Mary. I spoke with the present Riverdale while we were still in Bath and with Lord Molenor—husband of one of the Westcott sisters, you will recall—and the Duke of Netherby. Dorchester is the sort no man of sense would wish upon his daughter or sister. But there is nothing I can do, is there, if she is determined to have him?”

“Except be there,” she said. “You cannot be certain that your presence will be meaningless, Michael. If nothing else it will assure Viola that she is loved, that her family cares. And perhaps you will be surprised. Perhaps all your fears will be put to rest. The marquess is, after all, willing to do the decent thing.”

“But only because he was caught red-handed,” he said.

“You do not know that,” she said, taking his hand across the breakfast table. “You will be miserable if you do not go, Michael. You will feel that somehow you have failed her.”

“Again.” He frowned.

“Besides,” she said, smiling at him, “I cannot wait until Christmas to get my first glimpse of the notorious Marquess of Dorchester. Camille told me he is fearfully handsome.”

“Fearfully?”

“Her very word,” she said.

It was she who sat down a little later to write an acceptance while her husband stood behind her chair. His hands were clasped at his back, a frown on his face, as he resisted the inappropri

ate temptation to lean down to kiss the back of her neck.

At Morland Abbey, country seat of the Duke of Netherby, Louise Archer, née Westcott, the dowager duchess, waved her invitation in the air as the duke and duchess joined her and her daughter, Jessica, at the breakfast table.

“You have one too,” she said, indicating the small pile of mail that had been placed between Anna’s plate and Avery’s.

“I am overcome with joy,” Avery informed his stepmother, his voice sighing with ennui. “And what exactly is it we have one of? You may save Anna from having to read it for herself.”

“An invitation to Redcliffe Court,” Jessica blurted, “to a betrothal party for Aunt Viola and the Marquess of Dorchester. I thought only Aunt Viola and Abby were invited, but I think we all are. Lady Estelle Lamarr would hardly send invitations to us and to no one else in the family, would she? We must go, Mama. Please, please, Avery. I cannot wait to see the marquess. Camille says he is fearfully handsome despite the fact that he must be old.”

“My love,” her mother said reproachfully.

“Fearfully?” Avery’s quizzing glass hovered near his eye.

“It is the very word she used,” Jessica said.

He looked pained. “It would be a long journey for Josephine,” he said, looking at Anna.

“She has always traveled well,” she said. “Besides, I really must meet this fearfully handsome man. It is too long to wait until Christmas.”

“I must say,” Louise added, “that Camille chose the perfect word to describe the man. I cannot, however, like the idea of Viola marrying him. Perhaps my sisters and I can frighten him away, though I doubt he is a man easily intimidated.”

“Shall I answer the invitation for all of us?” Anna asked.

“Yes, do,” the dowager said while her daughter clasped her hands tightly on the edge of the table. “I shall have no peace from Jessica if I deny her the treat. Besides, I cannot deny myself.”

At Brambledean Court Wren found Alexander in the steward’s office and showed him the invitation. He said a few words to the steward and followed her out into the main hall before reading it.

“You must not do any unnecessary traveling while you are in a delicate condition,” he said.

“Must not?” She was smiling.

He looked up sharply. “Am I being the stuffy autocrat again?” he asked.

“Delicate?” She raised her eyebrows.

“You are with child, Wren.” He looked at her ruefully. “To me you are delicate. So is my child—our child. You both bring out my worst instincts to coddle and protect.”

“Or your best.” She set a hand on his arm. “I have never felt better in my life, Alexander. And you are head of the family.”

“If that were a physical thing,” he said with a sigh, “I would hurl it from the highest cliff into the deepest depths of the ocean.”

“But it is not.” Her eyes twinkled at him.

“But it is not.” He sighed again. “Let me go alone. You remain here.”

“I would pine away without you.” Her eyes were laughing now. “And you would pine away without me. Admit it.”

“Hyperbole,” he protested. “But I would be horribly inconvenienced and out of sorts.” He grinned suddenly. “I suppose you want to meet the infamous marquess before Christmas.”

“Camille described him as fearfully handsome,” she said.

“Did she really?” he said. “Fearfully? I suppose he does have a way of instilling fear in anyone who tends to be intimidated by pretension.”

“But you are not. My hero.” She laughed, and he laughed with her.

“We will go, then?” he said. “You are quite sure, Wren?”

“I am very fond of Viola,” she said. “She was not in London long when we got married, but there was an instant bond between us. Apart from your mother and sister, who were incredibly kind to me from the start, Viola felt like the first real friend I have had in my life. I am a little upset about her, for I fear that circumstances are forcing her into doing something she does not really want to do. I cannot do anything about that, of course, but I can . . . be there. It is not much to offer, is it?”

“It may be everything,” he said. “Why have we been standing here for so long? You will be getting dizzy. You will answer the invitation? And say yes?”

“I will.” She kissed him on the cheek. “You may return to what you were doing.”

“I have your permission, do I?” he asked.

“You do, sir,” she said. “You may have noticed that I can be a stuffy autocrat too.”

At Riddings Park in Kent, Alexander’s home until he inherited the Riverdale title and Brambledean with it, Mrs. Althea Westcott, his mother, read the invitation aloud to Elizabeth.

“I must have seen the Marquess of Dorchester a hundred times over the years,” she said, “but I cannot for the life of me put a face to the name.”

“Even though Camille describes him as fearfully handsome, Mama?” Elizabeth asked, her eyes twinkling. “And she is right too. I have to agree with her. He is both handsome and fearful. I would not like to cross his will. And he was not the Marquess of Dorchester until a couple of years or so ago. He was plain Mr. Lamarr before that.”

“Is Viola out of her mind agreeing to marry him?” her mother asked.

Elizabeth thought about it. “No,” she said, though there was some hesitation in her voice. “Although the marriage has undoubtedly been forced upon them—good gracious, his young son and daughter and her daughter were among the eight of us who came upon them there. It has been forced upon them, but I am not at all sure they would not have got there on their own, given time. There is something . . . Call me a romantic if you will. There is just . . . something. Words have deserted me this morning.”

“They are in love?” her mother asked.

“Oh,” Elizabeth said, “I am not at all sure about that, Mama. He is definitely not the sort of man one would expect to fall in love. It is widely believed, on good evidence, that he is a man without a heart. And I am not sure Viola is the sort of woman to fall in love. She is far too disciplined, something that has been so forced upon her all her adult life that it may well have become ingrained, I fear. But . . . Well . . .

“There is something,” her mother said, smiling.

“Just the word I was searching for. Thank you, Mama.” Elizabeth smiled. “There is something. We will go, then?”

“Certainly,” her mother said. “Was there ever any doubt?”

In the north of England, Mildred Wayne, née Westcott, was still in her dressing room having the finishing touches put to her morning coiffure when Lord Molenor, her husband, came in with their invitation dangling from one hand. He waited until his wife had dismissed her maid.

“Dorchester’s young daughter is inviting us to a betrothal party for Viola and her father at Redcliffe,” he said. “We have just returned home from Bath. With the boys away at school, perhaps behaving themselves, perhaps not, we have more than two months of quiet conjugal bliss to look forward to before we all take ourselves off to Brambledean for Christmas and the wedding. But I suppose you will insist upon going to Redcliffe as well.”

“Well, goodness me, Thomas,” she said, taking one last look at her image before turning from the glass, apparently satisfied. “Of course.”

“Of course,” he said with mock meekness, and offered his arm to escort her downstairs for breakfast. “And you may answer the invitation, Mildred.”

“Of course,” she said again. “Don’t I always?”

He thought about it during the time it took them to descend five stairs. “Always,” he agreed.

And at the home of the Dowager Countess of Riverdale, one of the smaller entailed properties of the earl, Lady Matilda Westcott, spinster eldest sister of Humphrey, the late Earl of Riverdale, offered her m

other the vinaigrette that she took from the brocade reticule she carried everywhere with her to cover all emergencies.

“We will not go, of course,” she said. “You must not upset yourself, Mama. I shall write and decline the invitation as soon as we have finished eating.”

“Put it away,” her mother said, batting impatiently at the vinaigrette. “The smell of it makes my toast taste vile. Viola is an important member of this family, Matilda. She was married to Humphrey for twenty-three years before he died. It was not her fault the marriage turned out to be irregular. I have loved her as a daughter for twenty-five years and I will continue to do so until I go to my grave. What I need to know is whether she is making a foolish mistake. Again. I understand this young man has a reputation every bit as disreputable as Humphrey’s was.”

“I would not know, Mama,” Lady Matilda said, holding the vinaigrette over her bag, reluctant to let go of it. “I have always been assiduous about avoiding him and gentlemen like him who really do not deserve the name. And he is not so young either. But Viola has no choice, you know.” She flushed deeply. “They were caught living in sin together.”

“Ha!” the dowager said. “Good for Viola. It is about time that girl kicked up her heels a bit. But I am concerned about her marrying the rogue. Why should she when all she did was kick up her heels? Half the ton—the female half—will feel nothing but secret envy if they ever find out, which I daresay they will. We will go, Matilda. You may write to Lady Estelle. No, I will do it myself. I want to take a good look at the young man. If I do not like what I see, I shall tell him so. And I shall tell Viola she is a fool.”

“Mama,” Lady Matilda protested. “You are overexciting yourself. You know what your physician—”

“Nothing but a quack,” the dowager said, thereby signaling an end to the entire discussion.