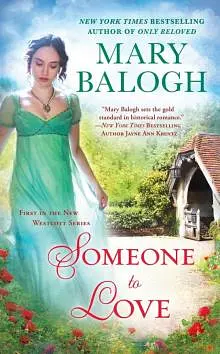

by Mary Balogh

“But what about Harry?” Abigail asked again.

“I do not know, Abby,” her mother said. “He must find some suitable employment, I suppose. Perhaps Avery will help him, though he is no longer bound by the guardianship his father agreed to.”

All eyes turned Avery’s way as though he had the answer to every question at the tip of his tongue. He raised his eyebrows. He was not in the habit of helping impecunious young men to find employment, especially wild young men who had been in possession of a seemingly bottomless coffer of funds until an hour or so ago and had been making profligate use of it. He fingered the handle of his quizzing glass, abandoned it, and sighed.

“Harry must be granted a day or two to stop laughing and telling everyone who will listen what a lark all this is,” he said.

“Oh, Avery!” Jessica blurted. “How can you make light of such a tragedy?”

He leveled a look upon her that closed her mouth and set her to huddling against her mother’s side, though she continued to glower at him.

“I am granting him a day or two,” he repeated softly. “For his laughter does not derive from amusement, and when he describes the morning’s disclosures as a lark he does not mean something that is fun.”

“Avery will look after him, Jess,” Abigail said, her eyes fixed upon him.

“Lady Anastasia seemed perfectly willing to share her fortune,” Cousin Elizabeth reminded them all. “Perhaps Harry will not need to take employment. Perhaps he—”

“I will not touch one penny of what that woman offers out of condescending charity, Elizabeth,” Camille said, cutting her off. “Neither, I trust, will Abby. Or Harry. How dare she even suggest it—as though she were doing us some grand favor.”

Which, in Avery’s estimation, was precisely what she would be doing if more sober consideration did not cause her to retract her offer.

“She is my granddaughter,” the dowager said.

“Is she returning to Bath, Avery?” Abigail asked.

“Brumford persuaded her to remain at least for the present at the Pulteney, where she apparently stayed last night,” he said. “He is to spend the afternoon there with her and her chaperone, doubtless boring her into a coma.”

“Poor lady,” Cousin Elizabeth said. “Her life has just changed drastically too.”

“I would not describe her as poor in any way, Elizabeth,” Thomas, Lord Molenor, said dryly.

“Her education as Lady Anastasia Westcott must begin without delay,” the dowager said, and everyone looked at her.

“After today,” Camille said, a world of bitterness in her voice as she got to her feet, “she will be able to move out of the Pulteney and into Westcott House, Grandmama. She will be thrilled about that.”

“Cam,” her mother said after heaving a sigh, “none of this is her fault. We need to remember that. Just think of the fact that she has spent all but the first few years of her life in an orphanage.”

“I cannot think of anything else but that,” the dowager said. “It is not going to be easy to—”

“I do not care where she has lived or how difficult it will be to bring her up to snuff,” Camille cried, rudely interrupting. “I hate her. With a passion. Do not ever ask me to pity her.”

“I am sorry, Grandmama,” Abigail said, getting up to stand by her sister. “Cam is upset. She will feel better after she has had a talk with Lord Uxbury.”

“Abby and Cam are not going to be staying here with us after all?” Jessica asked, teary eyed.

“Harry will stay here, I daresay,” the duchess said, “after Avery has found him. You must not worry about him, Viola.”

“My mind is too numb to feel worry,” the former countess said. “I suppose he is out getting drunk. I wish I were with him, doing the same thing.”

“Mama,” Jessica blurted, “promise me that woman will never, ever be allowed inside this house again. Promise me I will never see her again. I may well scratch her eyes out if I do. She is ugly and stupid and she looks worse than a servant and I hate her. I want everything to be back as it was. I want H-Harry back as the earl and laughing because he is h-happy, not because he is s-sad and can never be h-h-happy again. I want Abby to be my proper cousin again and still living close by. I want— I hate this. I hate it. And why is Avery not out looking for Harry and fetching him home?”

Avery dropped his glass on its ribbon, sighing inwardly, and opened his arms. She glared at him for one moment, then scrambled to her feet and dashed into his arms and buried herself against him. She would have climbed right inside if she could, he thought. She wept noisily and inelegantly against his shoulder, and he closed one arm about her and spread the other hand over the back of her head.

“Do s-s-something,” she cried. “Do something.”

“Hush,” he murmured against her ear. “Hush, love. Life is full of clouds. But clouds are lined with gold. You just have to wait for the sun to come out again. It will. It always does.”

Asinine words. He sounded worse than Cousin Althea had a few minutes ago. Where the devil did such drivel come from?

“Promise?” she said. “P-promise?”

“Yes, I promise,” he said, removing his hand from her head in order to fish out a large handkerchief from his pocket. Since women were always the ones who wept buckets of tears, it seemed illogical that they were also the ones who carried handkerchiefs so thin and dainty they were invariably sodden within moments of a cloudburst. “A cool glass of lemonade in the schoolroom will be just the thing for you, Jess. No, don’t protest. It was not a question.”

Her mother thanked him with her eyes as he led his half sister from the room, one arm about her waist.

He wondered what Lady Anastasia Westcott was doing at this precise moment and whether she had any idea at all of what was facing her—apart from a life of ease as a very wealthy woman, that is.

And he wondered where exactly Harry was. It would not be difficult, though, to find him later and keep an eye on him. He would be in one of his usual haunts, no doubt. And in one of those haunts he must be allowed to remain until he had stopped laughing.

Poor devil.

Six

Mr. Brumford handed Anna down from the carriage outside Westcott House early in the afternoon of the following day, and Miss Knox climbed down behind her, unassisted. Anna, looking both ways along South Audley Street and up at the house before her, saw that it was not quite as imposing as the mansion she had been taken to yesterday. Even so, everything here had been built on a lavish scale, and she felt dwarfed.

She owned the house.

She also owned a manor and park and farmland in Hampshire and a fortune so vast that her mind could not grasp the full extent of it. Her father had inherited part of the fortune from his father, but he had become unexpectedly shrewd in his later years and had doubled and then tripled it with investments in commerce and industry. The investments were still working to her advantage.

The knowledge of her wealth had actually made Anna feel quite bilious and even more desirous of going home to Bath and pretending none of this had happened. But it had happened, and she had reluctantly agreed to stay at least a few more days to consult at more length with her solicitor, for that was what Mr. Brumford had called himself—not just her father’s solicitor, but hers. Her mind was all bewilderment. She had to stay at least until everything was clear in her head and she understood better what it was all going to mean to her. Her life, she suspected, was going to change whether she wished it or not.

This morning Mr. Brumford had sent a message that he would accompany her when she arrived at Westcott House and again encountered her family. If they were to meet her at the house, did it mean her half brother and half sisters had recovered somewhat from their shock, and were prepared to welcome her, or at least to converse with her in a more amiable manner? But what about their mother, poor lady? Oh, th

is was not going to be easy.

The door opened even as she set her foot on the bottom step, and a manservant dressed all in black bowed and stood aside to allow her to enter. The hall was rich wood and high ceiling and marble floor with a wide, elegant wooden staircase—was it oak?—rising at the back of it to fan out to either side halfway up and double back upon itself.

A lady was descending the stairs—the one who had sat at one end of the second row yesterday, the duchess. Anna recalled that she had declared she would kill her brother if only he were still alive. Her brother—Anna’s father. This lady, then, was her aunt? Behind her, descending at a more leisurely pace, came the man who had stood throughout the proceedings yesterday, the one she had thought both beautiful and dangerous.

He still looked both today.

The duchess swept toward her, looking regal and intimidating. “Anastasia,” she said, sweeping Anna from head to foot with a glance as she came closer. “Welcome to your home. I am your aunt Louise, your late father’s middle sister and the Duchess of Netherby. Netherby, my stepson, is no direct relative of yours.” She indicated the man behind her. She completely ignored Mr. Brumford and Miss Knox.

“How do you do, ma’am,” Anna said. “How do you do, sir.”

The Duke of Netherby was dressed in a combination of browns and creams today. He was holding a gold-handled quizzing glass in one hand, upon the fingers of which there were two rings, one of plain gold, the other of gold inlaid with a large topaz stone. He was regarding her, as he had yesterday, from beneath slightly drooped eyelids with eyes that really were as blue as she remembered them. He had a lithe-looking figure and was no more than two or three inches taller than she.

“That ought to be Your Grace and Your Grace,” he said. He spoke with a light voice on what sounded like a sigh. “We aristocrats can be very touchy about the way we are addressed. However, since we have a sort of step-relationship with each other, you may call me Avery.” He turned his languid gaze upon Mr. Brumford and Miss Knox. “You may both leave. You will be sent for if you are needed.”

Anna turned. “Thank you, Mr. Brumford,” she said. “Thank you, Miss Knox.”

The lazy blue eyes held perhaps a gleam of mocking amusement when she turned back.

“We will go up to the drawing room, where your family is waiting to meet you,” the duchess, her aunt, said. “There is so much to be discussed that one scarcely knows where to begin, but begin we must. Lifford, take Lady Anastasia’s cloak and bonnet.”

A few moments later Anna walked beside her up the stairs while the duke came behind. They turned up the left branch from the half landing and at the top entered a large chamber that must overlook the street and was bright with afternoon sunlight. The fact that all this was hers would perhaps have taken Anna’s breath away if the people gathered in the room had not done it first. All of them had been present yesterday, and all of them were now silent—again—and turned to watch her.

The duchess undertook to make the introductions. “Anastasia,” she said, indicating first the elderly lady who was seated beside the fireplace, “this is the Dowager Countess of Riverdale, your grandmother. She is your father’s mother, as I am your father’s sister. Beside her is Lady Matilda Westcott, my elder sister, your aunt.” She indicated another couple farther back in the room, the woman seated, the man standing behind her chair. “Lord and Lady Molenor—your uncle Thomas and aunt Mildred, my younger sister. They have three boys, your cousins, but they are all at school. And standing over by the window are the Earl of Riverdale, Alexander, your second cousin, with his mother, Mrs. Westcott, Cousin Althea, and his sister, Lady Overfield, Cousin Elizabeth.”

It was all too dizzying and too much to be comprehended. All these people, all these aristocrats, were her relatives. But the only thing her mind could grasp clearly was that the people she most wished to see were not there.

“But where are my sisters and brother,” she asked, “and their mother?”

Everyone within her line of vision looked identically shocked.

“Oh, you will not be embarrassed by their presence, Anastasia,” the duchess assured her. “Viola left for the country this morning with Camille and Abigail—for Hinsford Manor, your home in Hampshire, that is. They will not remain there longer than a few days, however. Viola will take her daughters to Bath to live with her mother, their grandmother, and she herself will take up residence with her brother in Dorset. He is a clergyman and a widower. He and Viola have always been dearly fond of each other.”

“They have gone?” Anna felt suddenly cold despite the sunshine. “But I had hoped to meet them here. I had hoped to get to know them. I had hoped they would get to know me. I had hoped . . . they would . . . wish it.”

She felt very foolish in the brief silence that followed. How could she have expected any such thing? Her very existence had ended the world as they knew it yesterday.

“And the young man, my half brother?” she asked.

“Harry has disappeared,” the duchess told her, “and Avery refuses to search for him until tomorrow, assuming he has not returned of his own volition by then. You need not worry about him, however. Avery will see to his future. He was Harry’s appointed guardian when he was still the Earl of Riverdale.”

“It is my understanding,” the duke said, “that I inherited the guardianship of Harry himself from my late esteemed father, not just that of the Earl of Riverdale. I would rather dislike finding myself with Cousin Alexander as a ward. I daresay he would like it even less.”

“Oh, yes, he would indeed, Avery,” the new earl’s mother said. The Duke of Netherby was by now sprawled with casual elegance in a chair in a far corner of the room, Anna saw, his elbows on the arms, his fingers steepled. Miss Rutledge would have told him to sit up straight with his feet together and flat on the floor.

“Come and stand here, Anastasia,” the dowager countess, her grandmother, said, indicating the floor in front of her chair, “and let me have a good look at you.”

Anna came and stood while everyone, it seemed, had a good look at her. The silence seemed several minutes long, though it probably lasted no longer than half a minute at most.

“You have good deportment, at least,” the dowager said at last, “and you speak without any discernible regional accent. You look, however, like a particularly lowly governess.”

“I am lower even than that, ma’am,” Anna said. “Or higher, depending upon one’s perspective. I have the great privilege of being teacher to a school of orphans, whose minds are inferior to no one’s.”

The aunt who was beside the dowager’s chair gasped and actually recoiled.

“Oh, you may sheathe your claws,” the dowager said. “I was merely stating fact. It is not your fault you are as you are. It is entirely my son’s. You may call me Grandmama, for that is what I am to you. But if you did not call me that, ma’am would be incorrect. What would be correct?” She waited for an answer.

“I am afraid, Grandmama,” Anna said, “that any answer I gave would be a guess. I do not know. My lady, perhaps?”

“What are the ranks directly above and below earl?” the aunt—Aunt Matilda?—asked. “And what is the difference between a knight and a baronet, both of whom are Sir So-and-So? You do not know, do you, Anastasia? You ought to know. You must know.”

“I believe, Cousin Matilda,” the young lady by the window—the earl’s sister, Elizabeth?—said, “you are bewildering poor Anastasia.”

“And there are far more important matters to be dealt with,” the dowager countess agreed. “Do sit down, Matilda, and stop hovering. I am not about to fall out of my chair. Anastasia, those clothes are fit only for the dustbin. Even the servants would scorn to wear them.”

If it was possible to feel more humiliated, Anna thought, she could not imagine it. Her Sunday best!

“And your hair, Anastasia,” the duchess’s younge

r sister—Aunt Mildred—said. “It must be very long, is it?”

“It reaches below my waist, ma’am—Aunt,” Anna said.

“It looks thick and heavy and quite unbecoming,” Aunt Mildred told her. “It must be cut and properly styled without delay.”

“I will have a modiste come here with her assistants tomorrow,” the duchess said. “They will remain here until they have produced the bare essentials of a new wardrobe. Anastasia absolutely must not leave the house until she is fit to be seen. I daresay word has already spread among the ton. It would be strange indeed if it had not.”

“It was being spoken of in the clubs this morning, Louise,” the older man—Aunt Mildred’s husband—said. “Both the blow to Harry and his mother and sisters and the sudden discovery of a legitimate daughter of Riverdale’s. And Alexander’s good fortune, of course.”

“I have yet to discover what is good about it, Thomas,” the new earl said.

Looking at him, Anna concluded that her first impression of him yesterday had been quite correct. He was the most perfectly handsome man she had ever seen. He looked like the prince of fairy tales. She pictured herself describing him to the children in Bath while all the girls sank into a happy dream, imagining themselves as his princess.

“Do you know what the ton is, Anastasia?” Aunt Matilda asked sharply. She was seated now on a stool beside her mother’s chair.

“I believe it is a French term for the upper classes, Aunt,” Anna said.

“The very crème de la crème of the upper classes,” Lady Matilda told her. “We in this room are all of it, and so, heaven help us, are you. However are you to be whipped into shape when you are already twenty-five years old?”

It was hard not to strike back with equal sharpness and declare that she had no intention to being whipped into any sort of shape that was not of her own choosing. It was hard not to turn tail and stalk from the room and the house and find her way back home. Except that she had the feeling there was no real home at the moment. She was between two worlds, no longer belonging to the old and certainly not yet belonging to the new. All she could do was explore this new world a little more deeply and then decide what to do with the knowledge. She called upon all the resources of an inner calm and held her tongue.