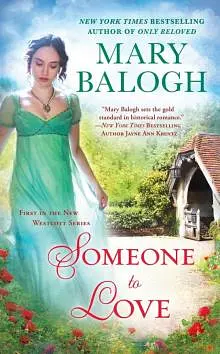

by Mary Balogh

“No,” she said. “Not short. I would like some of the length cut off, monsieur, if you will, and some of the thickness taken from it if that is possible. But it must remain long enough to be worn as I am accustomed to wear it.”

“Anastasia,” her aunt said, “you really must allow yourself to be advised. I believe Monsieur Henri and I know far better than you what is fashionable and what is most likely to make you appear to advantage before the ton.”

“I have absolutely no doubt that you are correct, Aunt,” Anna said. “I certainly appreciate advice and will always give consideration to it. But I would prefer to have long hair. Lizzie’s is long. Surely she is a fashionable lady.”

“Elizabeth is a widow of mature years,” her aunt said. “You, Anastasia, will be making a very late debut into society. We must emphasize your youth as best we can.”

“I am twenty-five,” Anna said with a smile. “It is not so very old or so very young. It is what it is and what I am.”

The duchess looked at her in exasperation and the stylist with sad resignation, but he set about cutting several inches off her hair and thinning it until she could feel the lightness of it and watch it swing about her face in a manner that gave life and even some extra shine to it. When it had been coiled again at the back of her head, a little higher than usual, up off her neck, it looked altogether prettier than Anna remembered its ever being.

“Oh, Anna,” Elizabeth said, offering an opinion for the first time, “it is perfect. It looks chic and elegant for daytime wear, yet leaves room to be teased and styled for more formal evening occasions.”

“Thank you, monsieur,” Anna said. “You are very skilled.”

“It will do,” her aunt said.

It was not the end of Anna’s ordeals, however. Her grandmother and other aunts arrived soon after luncheon and only just before Madame Lavalle and two assistants took up residence in the sewing room with enough bolts of fabric and accessories to set up a shop and piles of fashion plates for every type of garment under the sun. The modiste had been commissioned to clothe Lady Anastasia Westcott in a manner that would befit her station and permit her to mingle with the ton as the equal of all and the superior of most.

Anna was exhausted at the end of it. Not only had she had to be measured and pinned and prodded and poked; she had also been forced to look through endless piles of sketches of morning dresses and afternoon dresses, walking dresses and carriage dresses, theater gowns and dinner gowns and ball gowns, and numerous other garments—all of them plural, for one or even two of each would not do at all. She was going to end up with more clothes than all the ones she had ever owned put together, Anna concluded.

Even more overwhelming, perhaps, was the fact that apparently she could afford it all without putting even a slight dent in her fortune. Her aunts had all given her identically incredulous odd looks when she had asked the question.

She had fought several battles before they all withdrew to the drawing room for tea. Some she had lost—the number and type of dresses that were the bare essentials, for example. Some she had won simply by being stubborn, according to Aunt Mildred, and mulish, according to Aunt Matilda. Frills and flounces and trains and fancy lace trims and bows had all been firmly vetoed despite vigorous opposition from the aunts. So had low necklines and little puffed sleeves. She would be Lady Anastasia, Anna had decided, but she must also remain Anna Snow. She would not lose herself no matter how ferociously the ton might frown. And frown it would, Aunt Matilda had warned her.

Oh, and there was her court dress, over which she had almost no control whatsoever, since it was the queen herself who dictated how ladies were to dress when being presented to her—and Lady Anastasia Westcott must be presented, it seemed. Her Majesty expected ladies to dress in the fashion of a bygone age. Anna’s mind had not even begun to grapple with that particular future event yet.

The Earl of Riverdale arrived with his mother soon after they had settled in the drawing room. The earl—Cousin Alexander—actually commented upon how pretty Anna’s hair looked after bowing to all the ladies and before seating himself beside his sister and bending his head to talk with her. Anna found herself wondering if she was blushing and hoped she was not. She was unaccustomed to being complimented on any aspect of her appearance—especially by a handsome, elegant gentleman. He was looking at Elizabeth with a softened expression, almost a smile, and Anna felt a twinge of envy at the obvious closeness of brother and sister. Where was her own brother?

Their mother, Cousin Althea, sat beside Anna, patted her hand, agreed that her hair now looked prettier than it had, and asked how she did. But there was not much chance of conversation.

Aunt Matilda knew a lady of superior breeding and straitened means who would be only too happy to be offered genteel employment for a week or so, coaching Anastasia upon the subject of titles and precedence and court manners and points of fact and etiquette in which her education appeared to be sadly if not totally deficient.

Anna’s grandmother expressed doubt over whether Elizabeth was chaperone enough for Anastasia in such a large house and suggested again that Aunt Matilda take up residence with them. But before Anna could feel too much dismay, Cousin Althea spoke up.

“I would move here myself, Eugenia,” she said, addressing the dowager while patting Anna’s hand, “if I felt my daughter’s presence did not lend sufficient countenance to Anastasia. However, I am quite convinced it does.”

“Lizzie is the well-respected widow of a baronet and sister of an earl,” Cousin Alexander said.

No more was said on the subject. Anna suspected that her grandmother would have been happy to rid herself of Aunt Matilda’s oversolicitous attentions for a while.

Aunt Mildred knew of a dancing master employed by dear friends of hers to help their eldest daughter brush up on her dancing skills before her come-out ball. “Do you waltz, Anastasia?” she asked.

“No, Aunt,” Anna told her. She assumed it was a dance. She had never heard of it.

Aunt Louise clucked her tongue. “Engage him, Mildred,” she said. “Oh, there is a great deal to do.”

It was almost a relief when the Duke of Netherby strolled into the room following the butler’s announcement.

* * *

There were a dozen congenial ways—at the very least—in which he could be spending an afternoon, Avery thought. Prowling about his own home waiting for a drunken ward to awaken was not among them, though it was what he had been doing. And trotting around to South Audley Street to escort his stepmother home was not one either. Casually fond of the duchess he might be, but he did not involve himself a great deal in her life. Nor did she in his. Very rarely did he escort her anywhere. Nor, to be fair, did she expect it. And if he did go there to fetch her home, he would doubtless find himself knee deep in Westcotts and seamstresses and French hairdressers—were they not all French?—and Lord knew what else. Probably the very proper and very properly elegant Riverdale, with whom he had no sound reason to be irritated, would be there, for he was very definitely the sort who would escort his mother. Avery had every possible reason to pursue one of those dozen congenial activities and give South Audley Street a wide berth.

But that was where he found his feet leading him, and he did nothing to correct their course. He would see how well she was bearing up under the combined influence of a formidable grandmother and three aunts, not to mention one very proper earl and his mother and sister and some fake French persons. And she would wish to know that he had found and rescued Harry. For some reason it seemed she cared.

He was admitted to the drawing room to discover without surprise that they were all present except Molenor, who was probably ensconced in the reading room at White’s or somewhere similarly civilized, wise man. Avery made his bow.

Something had been done to her hair, something that probably did not fully satisfy the aunts since there was nothing fuss

ily pretty about it. For the same reason, perhaps, it ought to repel him too. But the knot on the back of her head no longer resembled the head itself in either size or shape and looked altogether daintier.

“Well, Avery?” his stepmother asked.

The whole room had gone silent as though the fate of the world rested upon his opinion. Anna was not wearing the Sunday dress today. She was wearing something lighter and cheaper and older. It was cream in color and might once upon a time have had some pattern on the fabric. But frequent washings and scrubbings in the orphanage laundry tub had worn it to near invisibility. Even so, the dress was a vast improvement upon the gloomy Sunday blue.

“Harry has been found,” he said, his eyes still upon her.

Her face lit up with what looked remarkably like joy. The aunts would doubtless work upon that until she learned never to display any emotion stronger than a fashionable ennui.

“I tucked him into a bed at Archer House late this morning,” he said, “after every inch of his person had been scrubbed and scoured and he had been forcibly fed by my valet, who also poured some concoction into him to counter the effects of an overindulgence in liquor. He will doubtless stir with the beginnings of a return to consciousness sometime soon, but he will be as cross as a bear and not willingly to be endured. I shall leave him to my valet’s care until later.”

“Oh.” She closed her eyes. “He is safe.”

There was a general murmur of relief from Harry’s relatives.

“Where did you find him, Avery?” Elizabeth asked.

“In company with an interesting collection of ragamuffins,” he said, “and a fierce, bald giant of a recruiting sergeant.”

“He has enlisted?” Riverdale asked with a frown. “As a private soldier?”

“Had enlisted,” Avery said. “I unenlisted him.”

“After the fact?” Riverdale said. “Impossible.”

“Ah,” Avery said with a sigh, “but I happened to have my quizzing glass about my person, you see, and I looked at the sergeant through it.”

“My poor boy,” the dowager countess said. “Why did he not simply come to me?”

“If the French but knew it,” Elizabeth said, “they would arm themselves with quizzing glasses instead of cannons and muskets and drive the British out of Spain and Portugal in no time at all with not a single drop of blood shed.”

“Ah,” Avery said, looking appreciatively at her, “but they would not have me behind all those glasses, would they?”

She laughed. So did her mother and Lady Molenor.

“Avery,” Anna said, bringing his attention back to her, “take me to him.”

“To Harry?” He raised his eyebrows. “He was not in the most jovial of moods before he went to sleep and will be worse after he has woken up.”

“I would not expect him to be,” she said. “Take me to him. Please?”

“Ah, but I will not force him to see you,” he told her.

“That is fair,” she said.

Nobody protested. How could they? She wished to see her brother, and the people gathered here were equally related to both.

Though he had come with the express purpose of escorting his stepmother home, Avery abandoned her to her own devices and stepped out for the second day in a row with Anna on his arm. Today, he thought idly, she looked more like a milkmaid than a teacher. One almost expected to look down and see a three-legged milking stool clutched in her free hand.

“What would you have done,” she asked him, “if the sergeant had refused to be cowed by your quizzing glass and your ducal hauteur?”

“Dear me.” He considered. “I should have been forced to render him unconscious—with the greatest reluctance. I am not a violent man. Besides, it might have hurt his feelings to be downed by a fellow Englishman no more than half his size.”

She gave a gurgle of laughter that did unexpectedly strange things to a part of his anatomy somewhere south of his stomach.

That was the entirety of their conversation. When they arrived at Archer House, he left her in the drawing room and went to see if Harry was still comatose. He was in the dressing room of the guest chamber that had been assigned to him, freshly shaved. He did not look any more cheerful, however, than he had earlier.

“You ought to have left me where I was, Avery,” he said. “Maybe they would have sent me off to the Peninsula and stuck me in the front line at some battle and I would have been mown down by a cannonball in my very first action. You ought not to have interfered. Do not expect that I am going to thank you for it.”

“Very well,” Avery said with a sigh, “I shall not expect it. I have your half sister in the drawing room. She wishes to see you.”

“Oh, does she?” Harry said bitterly. “Well, I do not wish to see her. I suppose you are going to try to drag me down there?”

“You suppose quite wrongly,” Avery informed him. “If I intended to drag you there, Harry, I would not try. I would do it. But I have no such intention. Why, pray, would it matter to me whether or not you go down to talk to your half sister?”

“I always knew you did not care,” Harry said with brutal self-pity. “Well, I’ll go. You cannot stop me.”

“I daresay not,” Avery said agreeably.

She was standing before the fireplace, warming her hands over the blaze—except that the fire had not been lit. Perhaps she was merely examining the backs of her hands. She turned at the sound of the door opening and gazed at Harry with wide eyes and ashen face.

“Oh, thank you,” she said, taking a few steps toward him. “I did not expect that you would see me. I am so glad you are safe. And I am so sorry, so very sorry for . . . Well, I am dreadfully sorry.”

“I do not know what for,” Harry said sullenly. “None of it is your fault. All of it is firmly on my father’s head. Your father’s head. Our father’s head.”

“On the whole,” she said, “I do not believe I was hugely deprived in never having known him.”

“You were not,” he said.

“Though I do have one memory,” she said, “of riding in a strange carriage and crying and being told by someone with a gruff voice to hush and behave like a big girl. I think the voice must have been his. I think he must have been taking me to the orphanage in Bath after my mother died.”

“He must have sweated that one out,” Harry said with a crack of bitter laughter. “He was already married to my mother by then.”

“Yes,” she said. “Harry—may I call you that?—your mother and sisters have gone into the country, though they do not intend to stay even there longer than it takes to have all their personal possessions packed up and moved out. They do not wish to know me. I hope you do, or at least that you are willing to acknowledge me and will agree to allow me to share with you what ought to be ours—all four of ours—and not mine alone.”

“It seems you are my half sister, whether I want you to be or not,” Harry said grudgingly. “I do not hate you, if that is what is bothering you. I have nothing against you. But I cannot . . . feel you are my sister. I am sorry. And I would not now accept even a ha’penny from that man who pretended to be my mother’s husband and my legitimate father. I would rather starve. It is not from you I will not take anything. It is from him.”

Avery raised his eyebrows and strolled to the window. He stood there, looking out.

“Ah.” The single soft syllable seemed to hold infinite sadness. “I understand. Now I understand. Perhaps in the future you will think differently and understand how it hurts me to be forced to keep it all. What will you do?”

“Avery is going to purchase a commission for me,” he said. “I don’t want him to, but he has made it impossible for me to enlist as a private soldier. It will be with a foot regiment, though. I am not going to have him kitting me out with all I would need as a cavalry officer. Besides, the officers of a foot re

giment probably care less than cavalry officers do about having a nobleman’s by-blow among their number. I will not have Avery buying me promotions either. I will move up in the officer ranks on my own merit or not at all.”

“Oh,” she said, and Avery would wager she was smiling, “I do so honor you, Harry. I hope you end up as a general.”

“Hmph,” he said.

“Then I will be able to boast of my half brother, General Harry Westcott,” she said, and Avery knew she was smiling.

“I will excuse myself,” Harry said. “I have the devil of a headache. Ah. Pardon my language if you will, Lady Anastasia.”

Avery heard the drawing room door open and close. When he turned from the window, Anna was back at the fireplace warming her hands over the nonexistent blaze. And he realized—devil take it!—that she was weeping silently. He hesitated for a few moments until she raised a hand and swiped at one cheek with the heel of it. She had turned her head slightly so that he could no longer see her full profile.

“He will look quite splendid in the green coat of the 95th Light Regiment,” he said. “The Rifles. He will probably cause stampedes among the Spanish women.”

“Yes,” she said.

But dash it all. Damn it to hell. He closed the distance between them, drew her into his arms, and held her face against his shoulder just as though she were Jess. Whom she was not. She stiffened like a board before sagging against him. Unlike most women under similar circumstances, though, she did not then proceed to melt into floods of tears. She fought them and swallowed repeatedly. She was virtually dry-eyed when she drew back her head.

“Yes,” she agreed, smiling an only slightly watery smile, “he will look splendid.”