Chapter Thirty-One

I’ll spareyou the gritty details of what comes next. Death, even surrounded by family, even with prayer and morphine working in tandem, is hard. There’s no do-overs, there’s no rehearsals.

Tyler arrives in more than enough time to have a moment with Mom. He does a better job of leading us through prayers than I did, and I gratefully relinquish the role to him, so relieved to have at least one thing off my shoulders.

At one point, Zenny whispers to me that this is like birth in a way, and she shows us Bell men how to lovingly doula Carolyn Bell through a different kind of labor. We rub her hands and feet, we stroke her hair. We pray and talk constantly, even when her eyes start drifting closed and her breathing shudders into a series of jagged moans and gasps. We never want her to feel alone, not even for a second.

The sun beams in, and without the constant drone of the ventilator and the incessant pinging of the monitors, we can hear the September wind whipping warmly by, a comforting late-summer sound.

It takes less than three hours, all told.

At the very last, the room lights on fire. It quartzes itself into an infinite glittering moment. It floods with vivid pain and joy and love and grief and I am opened up, I am melted away, and I feel God. For a blinding, breathless, reckless moment, I touch my fingertips to eternity.

And as I do, I also touch my fingertips to Mom in this place. As she is hovering, flashing, brilliant, a soul on her way to wherever bright souls go.

I’m shaking after. Shaking like a leaf and so is Tyler, and he meets my wet eyes with wet eyes of his own and says, “Did you feel it too?”

I nod and then look up at the monitors.

Mom is gone. It’s over and Mom is gone.

No one ever does drink the Shasta soda.

There’sa lot of shuffling around next. They clean up the body and do whatever medical things they need to do to verify her death, then they invite us back in for a last viewing. She looks peaceful now, nothing like the laboring woman earlier, and we look at her for a long time. Dad kisses her hair and her face and her lips for a final time. The rest of us stand around like men in shell shock.

Zenny’s gone and I don’t know when she left, and all of a sudden the strange rapture that came with Mom’s death pops like a pricked balloon, and I’m left flattened.

And yet there’s more to do.

There are the arrangements to make, what funeral home will take her and the remaining hospital business to finish up. There are the phone calls, three or four of them, different organizations asking for pieces of Mom. Her corneas. Her tendons. Her skin and heart valves.

It was her wish to donate as much as possible after her death and of course it’s logical—she doesn’t need any of those parts of her anymore—but it still makes my throat close with anger and tears. It’s like beating back carrion, being swarmed by vultures, and part of me just wants to scream she only just died, can we have a fucking minute before her body is stripped down for parts?

I don’t scream that. I follow her wishes, and try to take some comfort in knowing that there’s still something Carolyn Bell is doing for the world. That there’s another pocket of joy tucked into this day, and it’s that someone’s life will be materially better because my mom was here on this planet.

It’s still not easy.

After the hospital, we go back to Mom and Dad’s house and all of the Bell brothers proceed to get rip-roaringly, staggeringly drunk, sitting around the kitchen table and telling stories. Tomorrow, the funeral director will visit and all the arrangements will be finalized, tomorrow we’ll have to start calling and emailing and responding to condolences.

But tonight we grieve and laugh. Tonight we remember.

Later, as I lay in my childhood room, listening to Aiden and Tyler singing in the kitchen, the hole in my chest slowly stretches out beyond the borders of my body, it fills the entire room. It becomes a dark and massive mirror that beckons me to look inside. And inside I see my mother and sister, I see Zenny. I see God.

For the first time in my life, I look at the inside of myself. The ugly parts, the good parts, the parts in between. The grief both old and new, and the love for Zenny that flashes like a pulsar, a lighthouse for my soul, and the blue, swollen bruise of wanting her and the toothache-sweet feeling of loving her in spite of her leaving me.

For the first time in my life, I look inside myself and I just accept what’s there. I accept what I can’t control and what I can, I accept the parts of Sean Bell that simply are and the parts of Sean Bell that need to change. And the prayer I offer up isn’t one born out of anger or grief or gratitude or some other wild, fevered feeling. It’s simply an invitation for God to come sit at the mirror with me.

God does.

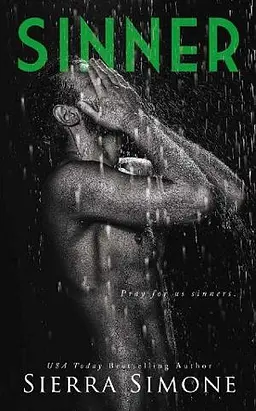

And that night, the warm September wind brings me a storm. A real one, with forcing gusts of wind and silver-black sheets of rain, and lightning fissuring the sky like it’s trying to pry it apart. Thunder rolls through the house, rattling the window, and I get out of bed, I pull on a pair of pajama pants, I go downstairs and out to the backyard.

I stand in the storm for what feels like hours, letting the rain sluice over my bare chest and back, letting it dance over my closed eyelids and against my parted lips. I let it fill up the hole inside me, I let it find every ridge and valley and vault of my body and my heart.

I hope Mom is dancing between the raindrops now, I hope she’s somewhere laughing and dancing with God.

And it comes to me like a clap of thunder that Zenny is under the same rain now, that somewhere this very same lightning-light is touching her face, and I can almost imagine it’s me touching her face. I can almost imagine the rain on my lips is her lips, the drops sliding down to my navel and over my hips are her fingers and her tongue. I can almost imagine she’s here with me now and I can say I’m sorry I wanted you to choose me, I’m sorry, I’m sorry.

I can say But have you ever seen yourself? Heard yourself? How could I ever want any different when you are who you are?

But she’s not here.

I’m utterly alone, except for—ironically enough—God.