by Jilly Cooper

‘Have a bath, darling,’ shouted Lizzie, desperately trying to tone down her face with green foundation.

‘I had a shower at the studios,’ said James, ‘so I’ve only got to change. We ought to leave in five minutes. How did you think my programme went?’

‘Wonderful,’ lied Lizzie, who hadn’t watched it, starting to panic. As it was dark outside, she couldn’t even make up in the car.

‘I’ll read you an extra story tomorrow, darlings,’ she told the children as they clung whining to her on the landing. ‘Or perhaps, Birgitta,’ she raised her voice hopefully, ‘will read you one before you go to bed.’

But Birgitta was watching James, who had decided on the white shirt after all, putting a pink carnation in his buttonhole. Poor Mr Vereker, she thought, looking so handsome in his dinner jacket, going out with such a frump. How much better would she, Birgitta, be in Lizzie’s place. James, however, hardly noticed his wife’s appearance. His was the one that mattered.

‘You look absolutely lovely, James,’ said Lizzie dutifully.

Low sepia clouds obscured the moon. As the headlamps lit up grey stone walls, acid green tree trunks and long blonde grasses, Lizzie tried abortively to apply eye liner as James described every little triumph of the planning meeting and his programme afterwards.

‘Anyone interesting in our party tonight?’ asked Lizzie as he paused for breath.

‘Rupert Campbell-Black, Beattie Johnson his mistress, Freddie Jones.’

‘Who’s he?’

‘Don’t you ever read the papers?’ said James, appalled. ‘Mr Electronics.’

Oh God, sighed Lizzie to herself. I daren’t ask what electronics are, and I bet I’m sitting next to him at dinner.

‘And Paul Stratton and his new wife.’

‘Oooh,’ squeaked Lizzie. ‘That’s exciting.’

Three years ago, just after the Conservatives won the last election, Paul Stratton, the Tory MP for Cotchester and the very upright Minister for Home Affairs, with a special brief to investigate sex education in schools, had rocked his constituency and the entire nation by walking out on Winifred, his solid dependable boot of a wife, and running off with his secretary half his age.

Not that his constituents were prudish (having Rupert Campbell-Black in the next door constituency, they were used to the erotic junketing of MPs), but as Paul Stratton had not only used his political career to feather his nest financially, but also set himself up as a pillar of respectability and uxoriousness, constantly inveighing against pornography, homosexuality, easier divorce and the general laxity of the nation’s morals, they had found it hard to stomach his hypocrisy.

‘Evidently, they’ve bought a place in Chalford,’ said James, ‘and Paul and Sarah, I think she’s called, are planning to spend weekends down here, re-establishing themselves with the local community.’

‘I suppose Tony inviting them this evening heralds the official return of the prodigal son,’ said Lizzie. ‘I wonder if she’s as beautiful as her photographs. I bet Rupert makes a pass at her. He’s always enjoyed bugging Paul.’

‘Don’t be fatuous, they’re only just back from their honeymoon,’ snapped James, steering round a sharp bend and bringing the conversation neatly back to himself.

‘I’ve got a gut feeling tonight is going to mark a turning-point in my career,’ he said importantly. ‘Tony’s been exceptionally nice to me recently. And when I popped into Madden’s office later this evening to find out exactly who was in the party, there was a confidential memo on Tony’s desk about the Autumn schedules, which I managed to read upside-down. It appears Corinium are committed to a series of prime time interviews for the Network. I didn’t dare read any more, in case Madden got suspicious, but I suspect Tony’s got me in mind, and that’s why he’s asked us this evening.’

Tony Baddingham soaked in a boiling Floris-scented bath, admiring his flat stomach. For once the cordless telephone was mute, giving him the chance to savour the prospect of the evening ahead. One of the joys of becoming hugely successful was that it gave you the opportunity to patronize those who, in the past, had patronized you. Paul Stratton, for example. It was going to be so amusing tonight extending the hand of friendship to Paul and his bimbo wife. How grateful and subservient they’d be.

Then there was Rupert. Tony was not given to fantasy, but more than anything else in the world he longed to be in a position when an abject, penitent, penniless Rupert, who’d somehow lost all his looks, was seeking Tony’s favour and friendship. The only reason Tony really wanted Rupert on his Board was in order to dazzle him with his brilliant business acumen.

In wilder fantasy, Tony dreamt of flaunting an undeniably sexy mistress, who would be impervious to Rupert’s charms.

‘Can’t you bloody understand,’ he imagined Cameron screaming at Rupert, ‘that Tony’s the only man there’ll ever be in my life?’

Tony added more boiling water to his bath to steel himself against the arctic climate of the rest of the house. There was a running battle between Tony who liked the heat, and whose office, according to Charles Fairburn, provided an excellent dress rehearsal, both physically and mentally, for hell fires, and Monica, his wife, who regarded central heating as a wanton extravagance which ate into one’s capital.

‘I still feel dreadfully guilty not telling Winifred about Paul and Sarah coming tonight,’ said Monica, when later, fully dressed, Tony went into his wife’s bedroom and found her sitting at her dressing table vigorously brushing her short fair hair. She was wearing the same emerald-green taffeta she’d worn for the last four hunt balls, which went beautifully with Tony’s diamonds, but did nothing to play down the red veins that mapped her cheeks, as a result of gardening and striding large labradors across the Gloucestershire valleys in all weathers. Yet, in a way, her rather masculine beauty, splendid on the prow of a ship or as a model for a Victorian bust of Duty, needed no enhancement.

Monica had once been head girl of her boarding school and had remained so all her life. Winifred Stratton, Paul’s ex-wife, had been her senior prefect. Together they had run the school firmly and wisely, diverting the headmistress’s attention away from a plume of cigarette smoke rising from the shrubbery, but gently reproaching the errant smoker afterwards. All the lower fourths had had crushes on Monica. Sometimes, even today, unheard by Tony who slept in a separate room, she cried, ‘Don’t talk in the passage,’ in her sleep.

Known locally as Monica of the Glen because of her noble appearance and total lack of humour, she was the only woman to whom Tony was always polite, and also a little afraid. In the icy, high-ceilinged bedroom, opera and gardening books crowded the tables on either side of the ancient crimson-curtained four-poster which Tony visited perhaps once a week. But even after eighteen years of marriage, these visits gave him an incredible sexual frisson.

On the chest of drawers, which contained no new clothes, were silver-framed photographs of their three children. With her sense of fairness, Monica would never let the other two know that she loved her elder son Archie, sixteen last week, the best. Nor that she loved her two yellow labradors, and her great passions, opera and gardening, often a great deal more than her husband.

Running Tony’s life with effortful efficiency, she never had enough time for these two passions, but if she was disappointed by the hand life had dealt her, she never showed it. She was not looking forward to this evening, which would involve talking until three o’clock in the morning to all those people Tony considered so important, but she would treat them with the same impersonal kindness whether they were Lords-Lieutenant or electronics millionaires. Always anxious to help humanity collectively (she did a huge amount for charity), Monica was not interested in people individually, or what made them tick or leap into bed with one another, but she was worried about Winifred. Even after she’d married Tony, and Winifred had married the much more brilliant, handsome and ambitious Paul Stratton, they had remained friends and gone to the opera and old school reunions together.

When Paul had run off with his secretary, in a scandal that rocked Gloucestershire almost as much as Helen Campbell-Black walking out on Rupert, Winifred had been utterly devastated, but like a building sapped by dry rot, one couldn’t initially see the damage from outside. After Winifred had moved to Spain with her two daughters in a desperate attempt to rebuild her life, Monica missed her friendship desperately, and now, to crown it, Tony had asked Paul and Sarah to join the party tonight, and she, Monica, was expected to smooth over Sarah’s first public outing in Gloucestershire.

‘I just feel it’s revoltingly disloyal to Winifred,’ repeated Monica.

She had applied Pond’s vanishing cream and face powder, and a dash of bright-red lipstick, which was the extent of her daytime make-up, and was now adding her night make-up: brown block mascara put on with a little brush.

‘I swore to Winifred I’d never have that little tramp’ – Monica spat on her mascara – ‘over the threshold.’

Tony’s brows drew together like two black caterpillars.

‘Paul is still our local MP, even if he has been booted out of the Cabinet,’ he said patiently. ‘With the franchise coming up next year, I have to entertain whatever wife he chooses. At least I waited until after they were married.’

As Tony moved forward to do up the clasp of her diamond necklace, Monica caught sight of her husband’s reflection. The red tailcoat with dove-grey facings made him look taller and thinner, and gave a distinction to his somewhat heavy good looks, but Monica hardly noticed.

‘I still ought to telephone Winifred and tell her.’

‘She’s in Spain. Let it rest. I’d better go down; they’ll be here in a minute.’

Monica glanced at her diamond watch. Lohengrin was about to start on Radio 3. If only she could stay at home and listen to it, she thought wistfully. As she slotted a three-hour blank tape into her radio cassette and pressed the record button, she called after Tony, ‘Can you tell Victor to up the proportion of orange juice in the Buck’s Fizz. We don’t want everyone arriving at the town hall plastered like last year.’

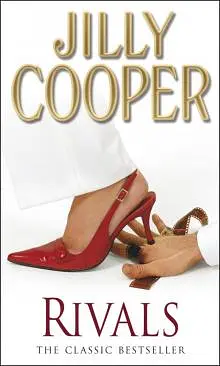

RIVALS

6

An hour later, downstairs in the huge dark panelled drawing-room hung with tapestries, members of the party were beginning to unthaw and retreat from the fierce red glow of the beech logs smouldering and crackling in the vast fireplace. Lizzie Vereker, sustained by at least six glasses of Buck’s Fizz, had perked up and forgotten her extra pounds and her straining red dress.

Neither Rupert nor Beattie Johnson had arrived yet, but there was plenty to gaze at. Paul Stratton’s new wife, for example, was absolutely gorgeous. She had entered the room looking little girlish and apprehensive, eyes cast down, clinging to Paul’s arm and hardly speaking. She was wearing a yellow silk dress which matched her thick piled-up gold hair, and a beautiful tobacco-brown fringed silk shawl covering her shoulders and wound high round her neck.

After replying in shy monosyllables to Tony and Monica’s questions, she had allowed herself to be introduced to James and also to Tony’s youngest brother, Bas, who was a terrific rake with black patent-leather hair, a smooth olive complexion, and a very overdeveloped little finger from twisting women round it. Now a small smile was beginning to play around Sarah’s full coral lips at Bas’s extravagant compliments, and the shawl was beginning to slip to reveal the most voluptuous golden shoulders and bosom. She and Paul must have been somewhere hot for their honeymoon, decided Lizzie.

Paul didn’t seem to have reaped the same benefit. His dark hair, which he’d once brushed straight back, had gone silver grey and been coaxed forward, almost to his eyebrows, and in little commas over his very pink ears. Sarah, being young, had obviously encouraged him into a Paisley bow-tie and a wing collar, the points of which kept being bent over by a new double chin. His once hard angular face seemed to have softened and weakened. He still, however, had the same all-embracing smile that passed over you like a lighthouse beam, and still liked the sound of his own voice. He was now talking to Freddie Jones, the electronics multi-millionaire.

‘Three million unemployed,’ he boomed, ‘is a Mickey Mouse figure. Didn’t you see that article about that factory manager who was offering people two hundred and twenty pounds a week merely to stuff mattresses, and simply couldn’t get staff? The working classes just don’t want to work. They’re shored up by moonlighting and the great feather bed of the welfare state.’

Paul made the mistake of thinking that someone with such capitalist instincts would automatically vote Tory. Freddie Jones listened to him carefully but didn’t say anything. He was plump and jolly, with rumpled red-gold curls, round, merry grey-blue eyes, a snub nose and an air that life was a tremendous adventure. Lizzie thought he looked much more fun than anyone else.

Across the room, she noticed, James had broken swiftly away from Sarah Stratton, and was now talking to a very slim woman with dimples and short brown curls tied up by a blue bow. She was wearing a pale-blue midi dress with a full skirt and a top, of which the satin lining was the strapless bodice, and the gauze over it covered her arms down to her wrists and her shoulders and tied in a pussy-cat bow at the neck. It was the most ghastly dress Lizzie had ever seen. But the woman, who Lizzie deduced must be Freddie Jones’s wife, seemed frightfully pleased with herself, and was laughing away, rolling her eyes and gazing up at James’s beautiful bronzed face with excessive admiration.

Apart from Sarah Stratton, Lizzie decided hazily, the men looked much more glamorous than the women this evening, gaudy peacocks in their different tail coats, red with grey-blue facings for the West Cotchester Hunt, red with crimson for the neighbouring Gatherham Hunt, dark blue with buff for the Beaufort. If he hadn’t been so good-looking, James in a dinner jacket would have been outclassed.

Helping herself to another Buck’s Fizz, Lizzie wandered somewhat unsteadily over to the seating plan for dinner at the Town Hall. She was sitting next to Freddie Jones. James was on Monica Baddingham’s right. Maybe his predictions about his brilliant future were about to come true.

Laughing uproariously, two handsome young bloods in red coats now rushed up and started marking the seating plan with red asterisks.

‘What are you doing?’ asked Lizzie.

‘Singling out the worst gropers,’ said one. ‘We’re starting with Bas Baddingham and Rupert Campbell-Black.’

‘Better put one beside my husband,’ said Lizzie.

‘Who’s he?’

‘James Vereker.’

‘We were just about to.’ They all collapsed with laughter.

‘Have some more fizz,’ yelled Monica Baddingham in her raucous voice, arriving with a jug which contained almost straight orange juice now. ‘I can’t think what’s happened to Rupert. We’ll have to leave in a sec, or we’ll be late for dinner.’ She drifted off.

‘Do we dare put an asterisk by Tony’s name?’ said one of the young bloods.

‘Of course,’ said the other, seizing the Pentel.

Giggling, Lizzie glanced across the room to see James beckoning imperiously.

He’s had enough of Mrs Jones, so he wants to palm her off on me and press the flesh, thought Lizzie.

Ignoring James, she turned back to the seating plan. Next minute James had crossed the room and seized her wrist.

‘May I borrow her?’ he asked coldly.

‘Of course,’ said the young bloods, ‘as long as you bring her straight back.’

James dragged Lizzie away. ‘Do pay attention when I signal.’

‘I was having a nice time.’

‘This is work,’ hissed James. ‘I want you to meet Valerie Jones. She’s opening a boutique in Cotchester next month. You must go and buy something. ‘

Never, never, thought Lizzie sulkily, if she sells dresses like that blue thing she’s wearing.

‘Lizzie writes novels,’ James told Valerie Jones, as if to explain his wife’s scruffy appearance.

‘I’d laike to wraite novels if I had the taime,’ said Va

lerie Jones, in an incredibly elocuted voice, ‘but Ay’m so busy with the boutique and the kids and moving in and we do have to entertain a lot. People are always saying, You should wraite a book, Mrs Jones, you’ve had such a fascinating laife.’

She screwed her face up in what she obviously thought was a fascinating smile.

Close up, Lizzie noticed that Valerie Jones had very clean nails, perfectly shaved armpits and the very white eyeballs of the non-reader and non-drinker. She was tiny and very pretty in a doll-like way, but Lizzie suddenly understood the expression: blue with cold. Valerie’s china-blue eyes were the coldest she’d ever seen. The pink and white skin also concealed the rhinoceros hide of the relentless social climber.

‘I’ll leave you girls to get acquainted,’ said James. ‘Better have a word with Paul Stratton, or he’ll think I’m avoiding him. We must have a dance later,’ he added admiringly to Valerie. ‘I bet you’re as light as thistledown.’

‘Seven stone on the scales this morning,’ simpered Valerie.

And six-and-a-half of that’s ego, thought Lizzie. ‘Where d’you live?’ she asked.

‘At Whychey,’ said Valerie.

‘Quite near us,’ said Lizzie. ‘We’re at Penscombe.’

But Valerie wasn’t remotely interested in where Lizzie lived.

‘And only quarter of an hour from the boutique, so Ay can rush down there, if there’s any craysis, or a special client comes in. They always ask for me.’ Valerie put her head on one side. ‘Ay don’t know why. Ay think Ay tell people the truth. Ay mean, what is the point of selling somebody a gown that doesn’t suit them? It’s such a bad advertisement for the boutique.’

‘Which house in Whychey?’ asked Lizzie.

‘Oh it’s lovely; Elizabethan,’ said Valerie. ‘We had to do an awful lot though, ripping out all that horrid dark panelling.’ Lizzie winced. ‘And of course we’ve completely re-landscaped the garden, but it’ll be a year or two before Green Lawns is the paradise we want.’