by Jilly Cooper

‘Tony Baddingham spent yesterday afternoon in a Stow-in-the-Wold motel with a woman. I’ve got pictures of them arriving separately and then leaving together, and exchanging kisses in the car park.’

He threw the pictures down on the table. Fascinated, Freddie and Declan got up to have a look. In the first photograph the woman had her black coat collar turned up and was wearing a black beret, dark glasses and her hair tied back. In the second, coming out of the motel, her coat was unbuttoned, she was laughing, holding the dark glasses and the beret in one hand, with her glorious red hair trailing down her back. In the third, she was kissing Tony in front of Taggie’s car.

‘Is this some kind of a joke?’ hissed Declan.

‘I’m afraid not,’ said the private detective. ‘I’m awfully sorry, Mr O’Hara. After they’d gone I talked to the receptionist. After I’d bunged her, she admitted they’d been there several times before. She showed me the register – they’d signed in as Mr and Mrs Jones. The girl remembered Mrs O’Hara because she was so beautiful.’

Declan started to shake. It was like seeing the first stroke of the woodcutter’s axe going into a great oak tree, thought Freddie.

‘But it was Bas, not Tony,’ muttered Declan.

‘Bas must have been a front,’ said Freddie.

‘Look how upset she was the other night when Taggie turned up with Bas,’ said Declan, frantically trying to convince himself.

‘That’s because she’s jealous of Taggie,’ said Freddie wisely. ‘It was only later she got really upset, which was when you told us you’d just seen Cameron with Tony – and she did know all about Dermot MacBride and the Shakespeare plays. ‘

‘I don’t believe it,’ muttered Declan. ‘She wouldn’t. I must find her.’ He stumbled towards the door.

‘For Christ’s sake, drive slowly,’ warned Freddie.

As Declan walked into The Priory Maud came out of the drawing-room with a glass of champagne in her hand. She was wearing a black polo-neck jersey, a black coat, black stockings, black flat shoes and a black beret on the back of her head. She was very pale, she wore no lipstick, but her skin had a glowing luminosity and her eyes were huge and dreamy. Declan thought she had never looked more beautiful, and suddenly knew she was as guilty as hell.

‘Darling – I got it!’ she said ecstatically.

‘What?’

‘The part – Nora – in A Doll’s House. We start rehearsing immediately after Christmas and they’re paying me four hundred a week, so our money worries are all over.’

How little she knows about anything, thought Declan – how can a child have done such terrible things?

‘Where’s Taggie?’ he asked.

‘Cooking supper, I think. You don’t seem very pleased for me, darling.’

As if in a dream he led her into the drawing-room, shutting the door and then opening it again to let in Claudius and Gertrude. Gertrude had a Bonio sticking out of the side of her mouth like a pipe. She could sit there for hours, saliva hanging in festoons. Declan leant against the door for support, watching Maud put a log on the fire. Despite all Maud’s grandiose plans for The Priory, there were still no curtains at the windows which were as black as her clothes.

‘How long have you been having an affair with Tony?’ he asked almost conversationally.

Maud’s face went as blank as a digital clock in a power cut.

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

‘Don’t prevaricate. I’ve got evidence.’ Declan threw the photographs down on the sofa. Slowly Maud examined them.

‘Rather good, that one.’ She took a leisurely sip of her champagne. ‘I might use it as a publicity photograph.’

‘How long’s it been going on?’

‘Since September.’

‘So you told him everything?’

Maud shrugged: ‘I really don’t remember. We found so much to talk about.’

This can’t be happening to me, thought Declan. I don’t feel anything. It’s as though we’re discussing two characters in a play.

‘But why Tony? Bas I can understand, but not —’ for the first time he betrayed any emotion – ‘not that filthy venomous toad.’

Maud looked at him for a moment, her hand gently stroking Claudius’s ears.

‘Because he was kind, because he listened to me, because he was interested in me as a person – not just as a hole between two legs.’

Her sudden uncharacteristic coarseness shocked Declan almost more than her betrayal.

‘Tony!’ he said in amazement, ‘kind?’

Suddenly Maud flipped. ‘You’re so obsessed with your fucking franchise,’ she yelled, ‘you don’t know anyone else exists, except when you want to fuck them. You couldn’t even forget it for one moment to get back for my first night, when I really needed you. Christ – I needed you! And then swanning in and ordering me away from my own first-night party.

‘I was only fooling around with Tony until then. It was only after that that it got serious. He arranged for me to meet Pascoe Rawlings. He saw that a car delivered me to Pascoe’s office last week and brought me back. He fixed for me to be driven to the audition today, and even though he’d got his IBA meeting this afternoon, he still rang me this evening to see how I’d got on. You’d even forgotten I was going.’ She laughed; it was a horrible sound without any merriment. ‘The great interviewer, so praised for his judgement of character and his consideration to the staff, who doesn’t know a thing about his own wife.’

‘Can’t you understand that he’s using you?’ said Declan slowly. ‘The only thing that turns Tony on is acquisition. You’ve just lost us the franchise, and you were going to stand by and let me blame Cameron.’

‘Serve her right – arrogant little bitch,’ cried Maud hysterically.

Outside in the hall Taggie could hear her mother’s screams getting louder and louder. Oh God, her father didn’t need upsetting any more when he had the IBA meeting in the morning. Next moment the drawing-room door burst open.

‘I’m leaving you,’ screamed Maud.

‘Come back,’ roared Declan.

‘Never, and don’t send Ursula looking for me at the Lost Property Office, because I won’t be there.’ She shot past Taggie and out of the front door, banging it so hard the whole hall rattled.

Taggie ran to open it. Outside it was snowing again. She watched Maud drive off in her car, hell for leather, down the drive.

‘What on earth’s the matter?’ she said, turning to Declan, who was standing as if blasted white by lightning.

‘She was the mole.’

Taggie gave a gasp. ‘She couldn’t be. She can’t have meant to.’

‘She did,’ said Declan in a voice of utter despair, ‘because I neglected her. It’s all my fault. I blamed Cameron last night and Rupert today, and just now I blamed her. But through my focking obsession and hubris I’ve brought us all down.’

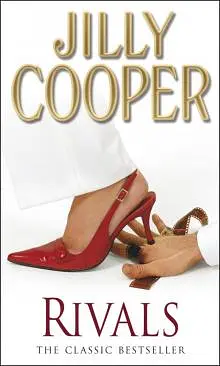

RIVALS

50

For Rupert next morning the press was crucifixion – ranging from highly moralistic pieces about the chronic Tory failure to keep their noses clean to double-page spreads with pictures charting the rise and fall of the Tory party golden boy. The tabloids had dug up several of Rupert’s more bitter exes, who, having done a great deal more than kiss, were now only too happy to tell. The seamiest tabloid of all had a huge frontpage headline: ‘Campbell-Blackguard,’ above an enchanting picture of Tabitha.

‘In the playground of exclusive Bluebell’s school (fees £1,500 a term),’ ran the copy, ‘a little child sobs alone. In a voice hardly above a whisper, Tabitha Campbell-Black told the Scorpion:

‘“I don’t mind my friends not playing with me any more, but I don’t want Daddy to die of AIDS.”’

‘This is the final fucking limit,’ howled Billy Lloyd-Foxe, hurling the Scorpion across the room. ‘I’m coming with you to the IBA.’

‘The Beeb will sack you if they find out,’ said Janey, who was painting her nails because it was less

hassle than cleaning them. ‘And as I turned down a hundred grand yesterday to tell all about our life with Rupert, and this suit cost nearly as much, I don’t think you can afford to.’

‘I don’t care,’ said Billy mutinously. ‘Rupert’s my best friend, and anyway since Beattie implied I was gay yesterday, I shall certainly be snapped up by Radio 3.’

At Freddie’s house, the remnants of the Venturer consortium gathered before the meeting. With no Bishop, no Professor, no Cameron and none of the moles, their numbers were utterly depleted and their bid in tatters. The second day of Rupert’s memoirs was even worse, with intimations of underage school girls. Freddie had spent half the night trying to persuade a demented Declan that they’d got to shop Tony, not just for seducing Maud and bugging their houses, but because Seb was working on excellent evidence that Tony had bribed Beattie Johnson to sing to the rooftops, just at a time when it would be most damaging to Venturer.

But like Wellington at Waterloo refusing to turn the guns on the enemy commandant, Declan refused to let anyone condemn Tony. He didn’t want Maud’s name dragged into it. He was clearly still suffering from shock. He looked terrible.

‘A black ram is tupping my white ewe,’ he kept saying over and over again, ‘and it was all my fault.’

Rupert, who arrived with Bas, didn’t look much better, but at least he’d got a grip on himself. The meeting had to be got through. There were people not to be let down, there would be the rest of his life to mourn for Taggie and probably his children as well. Helen had rung this morning, saying she was applying for a court order to deny him access.

Even Henry Hampshire arrived walking wounded, wearing a dark suit with uncharacteristically flared trousers, and with his leg in plaster.

‘Horse put its foot down a rabbit hole,’ was all he would say about it.

‘’Morning.’ He went up to Rupert, who was huddled on the sofa trying to keep down a cup of coffee. ‘Enjoying your memoirs; great stuff.’ He lowered his voice. ‘I had a crack at Mandy Hamilton myself twenty years ago. God, she was pretty. Might have made more progress if I’d known she liked having her bottom smacked.’

Rupert managed a pale smile. ‘At least it kept you out of the papers.’ Then, also lowering his voice, he added, ‘Look, I don’t think there’s any chance now of us getting the franchise. Tony’s now odds on and we’ve gone way out.’

‘Better have a bet then,’ said Henry, limping towards the telephone. ‘Anyway, I’ve had more fun in the last six months than I can ever remember. We’ll have to bid for another area next time.’

Dame Enid arrived next, resplendent in a pinstriped trouser suit with an even wider white stripe than Tony’s, a bright blue tie, and an Al Capone hat.

‘Stick ’em up, it’s a shoot out,’ said Marti Gluckstein, who came with her. He was dressed in a lurid green Norfolk jacket and knickerbockers, and sucking on a pipe.

‘Did you get that at Valerie’s boutique?’ said Bas, then hastily shut up in case Freddie overheard.

‘Thought I ought to appear as the country squire,’ said Marti. ‘Where’s the Bishop?’

‘Pulled out, I’m afraid,’ said Freddie, handing him and Dame Enid cups of coffee.

‘Good riddance, pompous old fart,’ said Dame Enid, helping herself to sugar. ‘Can’t you pull a rabbi out of a hat to replace him?’ she added to Marti.

Marti smirked. ‘For you, my dear, anything.’

‘Crispin Graystock’s pulled out too,’ said Freddie.

‘Well, thank God we’ve got rid of the two worst wafflers,’ said Dame Enid philosophically. ‘Graystock’s got complete verbal diarrhoea.’

‘Which reminds me,’ said Henry, hobbling off at great speed towards the lavatory, ‘had the most ghastly trots all night. Sure I’m going to botch my answers.’

The moment he arrived, Lord Smith went straight up to Rupert. ‘Really feel for you, lad,’ he said. ‘But everyone regards the Scorpion as fiction. That Beastly Johnson did me over once. Took down what I said, but twisted it like barley sugar. I’ve got a message from Alf Smithers. Chairman of the FA,’ he added, by way of illumination, when Rupert didn’t react.

‘I know,’ said Rupert flatly. ‘He was my cross.’

‘He’s not cross now. Told me to wish you luck today. Said you were the best Sports Minister they’ve ever ’ad. They all wish you’d come back. What’s up with Declan?’

‘Wife trouble,’ said Rupert.

‘Happens at franchise time,’ said Lord Smith. ‘When we bid for the Midlands eight years ago, the wives got so fed up, they was all at it – even mine.’

‘Only two more to come,’ said Freddie, trying to cheer up his own and everyone’s spirits. ‘And ’ere they are,’ he went on, as Seb and Charles came through the door.

‘We’re going to have a fuller house than you thought,’ said Charles. ‘I’ve just seen Billy, Janey, Harold White and Sally Maples getting out of a taxi.’

Freddie had tears in his eyes as he welcomed them. ‘You shouldn’t have come. It’s totally out of order,’ he said. ‘I know what you’re risking, but I won’t say I’m not bloody pleased to see you.’

Declan seemed hardly to notice, but Rupert’s jaw quilted with muscles when he saw Billy. ‘You’re fucking insane,’ he said roughly.

‘I like “lorst” causes, as Henry would say,’ said Billy cheerfully. ‘Anyway, I brought you luck at the LA Olympics. And you brought me luck, too. If I hadn’t done the commentary for the BBC, they’d never have given me a job.’

‘Which you’re about to lose.’

As the hands of the clock inched past nine-thirty, they decided that there was no point waiting any longer. Cameron wasn’t coming.

‘Pity,’ sighed Hardy Bissett, going round straightening ties. ‘Now, don’t forget, no sniping – solidarity is all. Sit up straight. Burst with enthusiasm. You’re bursting a little too much, Janey darling.’ He did up two buttons of her shirt. ‘Although, on reflection, if you’re sitting anywhere near the Prebendary, undo them again and press your elbows together.’

It was still bitterly cold when they set out for the IBA in their cars. The snow in the park was the colour of dirty seagulls. In High Street, Ken. the shop windows with their jolly snowmen, spangled Christmas trees and mufflered bright-eyed tots hurling snowballs were at variance with the sullen sky outside, and the shoppers shuffling blue-lipped and bad-tempered along the slushy pavements.

Janey’s scent was making Rupert feel sick. In a greengrocer’s shop, he noticed, they were already selling mistletoe, the one thing he wouldn’t need this Christmas.

‘Oh look, there’s Father Christmas,’ said Janey, pressing a button to lower the window, as the car swung round The Scotch House into Brompton Road.

‘Please Santa,’ she called out to him, as he marched alongside the car, ‘will you put a franchise in my stocking?’

‘Ho, ho, ho,’ said Father Christmas, hoisting his sack onto his back and batting his long black eyelashes at Janey. ‘For a pretty little girl like you, I just might.’

‘My Christ,’ said Janey, with a scream of laughter, as he turned right in front of the car and strode purposefully across the road through the revolving doors of the IBA. ‘It’s Georgie Baines.’

‘I wish I’d thought of that,’ said Charles petulantly. ‘I wanted to come as Gwendolyn Gosling again, but I thought I’d better play it straight.’

To avoid the press, and preserve the utmost security, the convoy of cars turned right down Lancelot Place, entering the IBA from the back by the underground car park. From here their passengers were whisked up to the eighth floor and, although the moles nervously looked for reporters in every dark corner, they were all safely led along the corridor and installed in an empty office.

‘I feel like a courtier waiting for an audience with Louis XIV: “Please don’t banish me to my estate in the Loire, Sire”,’ said Charles, as he peered out of the window on to another IBA block of offices, where every secretary seemed

to be clutching paper cups of coffee and reading Rupert’s memoirs.

‘God, I’m nervous,’ said Henry, mouthing the answers to possible questions. ‘D’you think I should say brilliant wild life “photographer” or “cameraman”?’

‘Cameraman,’ said Billy. ‘Photographer is press, and we don’t like them very much at the moment.’

‘I wish I could take in a calculator,’ said Marti in a hollow voice.

‘D’you think they’ll shine lights in our faces?’ asked Janey.

‘They didn’t yesterday, but then Corinium has a better track record,’ said a voice. It was Georgie Baines, who’d shed his Father Christmas disguise and was now wearing a dark suit and fluffing up his dark curls.

Everyone crowded round him in delight.

‘Of course! You went in yesterday afternoon with Corinium,’ said Freddie.

‘Wearing a different tie,’ said Georgie.

‘How long were you in there?’ asked Seb.

‘Exactly an hour,’ said Georgie.

‘What was it like?’

‘Falling off a log. Not one difficult question. Tony’s star is definitely in the ascendant, that’s why I’m here. I’ve always believed rats should desert a rising shit.’

‘How did you manage to get away?’ asked Janey, removing a last bit of white beard from Georgie’s chin.

‘Tony thinks I’m at Saatchi’s.’

A female IBA official was going spare trying to organize everyone’s entrance into the board room in a pre-ordained order, so the Authority would know who they were.

‘I expected eleven people,’ she said in bewilderment. ‘There seem a great many more. I know who you are,’ she said to Janey, ‘and you,’ she said to Rupert, keeping her distance, ‘and you,’ she turned to Declan, looking perplexed as though she hardly recognized him.