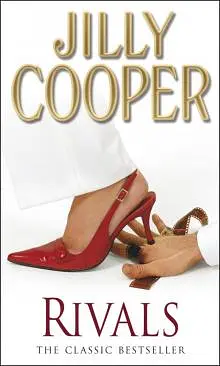

by Jilly Cooper

‘Better than your revolting clodhoppers,’ said Maud furiously. ‘It’s like sharing a house with a carthorse. And what are you going to do with yourself all day?’

‘I’m going to spend the morning dyeing my hair,’ said Caitlin.

Cotchester was full of tourists, drifting aimlessly down the High Street, photographing the cathedral and the ancient houses, and the statue of Charles I. By contrast, Monica Baddingham, striding purposefully through the crowds, was like a powerboat chugging through a flotilla of yachts on a windless day. She detested shopping – such a time-consuming activity. But she needed batteries for her Walkman and there was a new recording of Don Giovanni on order which, maddeningly, hadn’t arrived, and she had to pick up some scores of The Merry Widow.

Every year the West Cotchester Hunt put on a play which was performed to large noisy audiences in November. This year they had decided to be slightly more ambitious and join forces with Cotchester Operatic Society to put on The Merry Widow.

Monica had already been appropriately cast as Valencienne, a virtuous wife. Charles Fairburn had been inappropriately cast as her randy admirer Camille. Bas Baddingham was still dickering over whether to play the male lead, Count Danilo, but as yet the director, Barton Sinclair – ex-Covent Garden, no less – was still searching for someone to play Hanna, the Merry Widow. He was holding auditions in Cotchester Town Hall that very day, but was deeply pessimistic that anyone would be beautiful or stylish enough, or have a sufficiently good voice. Luck, however, was on Barton Sinclair’s side. Outside the Bar Sinister Monica bumped into Maud.

‘How jolly nice,’ said Monica in her raucous voice as she kissed Maud. ‘I’ve been hoping I’d run into you for ages. I wanted to say how wonderful Taggie’s been. Completely saved my life cooking for all the hordes this summer. You must be so proud of her.’

Maud said, yes, she supposed she was.

‘But she’s getting too thin,’ went on Monica. ‘She used to be so round, soft and smiling. I hope she’s not taking on too much. You, on the other hand, look splendid. How’s Declan?’

‘Oh, obsessed with the wretched franchise,’ said Maud fretfully.

‘Isn’t it a ghastly bore?’ sighed Monica. ‘Tony can’t think of anything else. But I don’t see why, just because our husbands are on different sides, we can’t be friends.’

It was very hot in Cotchester High Street. The cool garlicscented gloom of the Bar Sinister beckoned.

‘Nor do I,’ said Maud. ‘Why don’t we go in and have lunch?’

‘What a good idea,’ said Monica in excitement. ‘Ploughman’s lunch, and half a pint of cider.’

Maud’s aims were slightly more ambitious, and they were soon sitting down with Muscadet and crespolini.

‘Oh, look, there’s James Vereker and Sarah Stratton,’ said Monica. ‘What’s Declan doing at the moment?’

‘He’s off to Ireland with Cameron Cook,’ said Maud.

‘Oh.’ Monica’s forkful of crespolini stopped on the way to her mouth. ‘But I thought . . .’

‘. . . she was living with Rupert. Yes, she is, but she’s making a film with Declan in Ireland.’

Her tongue loosened by a third glass, Maud told Monica about Declan’s trying to persuade her to play Maud Gonne, and how her nerve had failed. ‘I couldn’t face Cameron screaming at me when I didn’t come up to scratch,’ she confessed. ‘Her sarcasm could strip furniture, and I’ve always found it difficult to act in front of Declan.’

Monica, at this point, became very thoughtful. ‘But you would like to go back?’

‘Oh yes, but at the moment I’ve got about as much self-confidence as a leveret at a coursing meeting.’

Monica fished in her shopping bag and brought out one of the scores of The Merry Widow. On the cover was a painting of a beautiful woman, with hair swept up under a big pink hat and a waist, in its swirling cyclamen-pink dress, as slender as her neck. She was raising a glass of champagne in one long purple-gloved hand. Four handsome men with black twirling moustaches were raising their glasses to her in admiring salute.

It was Maud’s perfect fantasy. What did gel and Sun-In matter to that woman?

‘Why don’t you start with something less ambitious than Maud Gonne?’ said Monica. ‘We’re desperate for someone to play the Merry Widow.’

‘I couldn’t,’ faltered Maud. ‘It’s a very demanding part.’

‘Nonsense,’ said Monica briskly. ‘You’d waltz it.’

‘What are my two favourite women doing lunching at my restaurant without telling me?’ said a voice.

It was Bas, absolutely black from a fortnight’s polo in America.

‘Bas,’ said Monica delightedly. ‘I know I’m not supposed to talk to you either, after the dreadful way you’ve betrayed Tony, but sit down and help me persuade Maud to audition for Hanna.’

Bas needed little persuading. Up to now he’d by-passed Maud in his amorous travels, partly because he had long-range aims for Taggie and partly because he’d realized how dotty Maud had been about Rupert at Christmas. Certainly, in the soft lighting of the Bar Sinister, she looked stunning today, and that violet dress was very becoming. It emphasized her white skin and just missed clashing with the gorgeous red hair, and all those undone buttons showed off a Cheddar Gorge of cleavage. Another bottle of Muscadet was ordered.

‘Bas is toying with the idea of playing your leading man,’ said Monica.

‘Hopefully it’ll lead to other things,’ said Basil, rubbing one of his long muscular, polo-playing thighs against Maud’s as he re-filled her glass.

Later, not even allowing her a cup of black coffee to sober her up, Basil and Monica frogmarched Maud down the High Street to the Town Hall where the director, Barton Sinclair, had reached screaming point, having heard ten amateur hopefuls murdering the score.

Up on stage now, the eleventh, a very made-up blonde, who’d never see fifty again, was crucifying the Vilja song. The pianist was desperately trying to keep in time with her. A huge bluebottle buzzing against a window pane was having more success.

‘She’d be too fat even if you looked through the wrong end of your binoculars,’ whispered Bas to Maud. ‘At least you can do better than that.’

‘I can’t,’ muttered Maud in terror. ‘That’s Top G she’s missing.’

As she tried to bolt, Bas’s arm closed round her waist. ‘Yes, you can,’ he murmured. ‘Just think of the fun we can have rehearsing together night after night, and it won’t be all singing I can tell you.’

‘Thank you very much,’ said Barton Sinclair in his chorus-boy drawl.

‘I sang the part in 1979,’ said the blonde, teetering down the steps in her four-inch heels. ‘It brought the house down.’

‘Pity you weren’t buried under the rubble,’ muttered Barton. ‘We’ll be in touch. I’ll be making a decision at the end of the week,’ he told her. Then, waiting until she was safely out of the door, he turned to Monica. ‘That’s the lot, thank God. Talk about scraping the barrel organ.’

‘I’m going home,’ said Maud.

‘Could you hear just one more?’ said Monica.

Barton Sinclair looked at his watch and sighed: ‘Do I have to? I was hoping to get the three forty-five back to Paddington.’

‘It’ll be worth getting the next train, I promise you,’ said Monica. ‘This is Maud O’Hara. She used to act and sing professionally.’

Barton Sinclair straightened his flowered tie, and smoothed his straggly mouse-brown hair.

‘You certainly look the part,’ he said.

‘I haven’t practised,’ bleated Maud, the crespolini and the Sancerre churning like a tumble-dryer inside her.

‘Try the same song,’ said Barton, handing her the score. ‘Take it slowly, Mike,’ he added to the pianist.

‘You come in on the last quaver of the fourth bar,’ the pianist told Maud kindly.

Below her, Maud could see their faces: Monica’s eager, flushed and unpainted, Basil’s sleek and maho

gany, and Barton Sinclair’s London night owl and deathly pale. They seemed infinitely more terrifying than a first night audience at Covent Garden.

‘I can’t,’ she whispered, wringing her sweating hands.

‘Go on, darling,’ said Bas. ‘We’re all on your side.’

Off went the pianist. Maud fluffed the opening.

‘I’m sorry. Could we start again?’

‘Of course,’ said Barton.

Off went the pianist again, and Maud opened her mouth.

There once lived a Vilja, a fair mountain sprite,

She danced on a hill in the still of the night.

Her voice was sweet, true and hesitant, but suddenly, as she launched into the main theme, it seemed to soar out glorious and joyful, stilling the bluebottle and taking the dust off the rafters, and the four other people in the room felt the hair rising on the backs of their necks.

‘A star is re-born,’ whispered Monica, wiping her eyes.

‘I am going to have a nice Autumn,’ reflected Basil. ‘Over forty, they’re always so grateful!’

‘Vilja, Oh, Vilja, be tender and true,’ sang Maud, triple pianissimo, ‘Love me and I’ll die for you.’

For a second there was silence, then her audience burst out clapping and cheering.

‘Come into Covent Garden, Maud,’ sang Basil.

‘You’ve got the part,’ said Barton Sinclair. ‘The only problem is how much you’re going to show up the others.’

‘Thank you, Barton,’ said Monica and Basil in unison.

After that they all went back to the Bar Sinister for several more bottles of Muscadet and Barton Sinclair only just made the six forty-five.

Tony and Declan were very apprehensive when they heard the news of such close fraternization between the rival franchise sides. On reflection, however, Tony decided he’d definitely got the better bargain. While Maud was a rattle who drank far too much, Monica drank very little and was incredibly discreet.

‘Keep your trap shut and your ears open,’ Tony told her. ‘You may learn some interesting things.’

‘I’m not pumping anyone,’ said Monica firmly. ‘It’s simply not on. Only if anyone lets anything drop.’

‘It’ll be knickers if Bas has anything to do with it,’ said Tony.

Declan, however, who was going to have to spend the second half of September and much of October in Ireland with Cameron, was principally relieved that Maud was so much happier. The sound of her carolling away upstairs practising her songs reminded him of the carefree days in Dublin when they were first married. Perhaps, if The Merry Widow were a success, she’d have enough confidence to take up acting professionally again.

Caitlin, who had now dyed her custard-yellow hair so black it almost looked blue, found her mother’s euphoria even more irritating than her previous picky depression, and decided to push off to London for a few days to stay with some schoolfriends. She was going back the week after next and might as well have some fun before the prison doors clanged round her again.

She found Taggie in the kitchen fainting over a final reminder from the Electricity Board. ‘I can’t think why it’s so high.’

‘Mummy’s vibrator’s battery-operated, so it can’t be that,’ said Caitlin. ‘Hullo, darling,’ she added, hugging Claudius.

‘He’s in disgrace,’ sighed Taggie. ‘He’s just eaten one of Mummy’s new slingbacks.’

‘Good thing; they were gross,’ said Caitlin. ‘Every Claud has a silver lining! Can you lend me fifty pounds to go to London?’

‘I haven’t got it,’ protested Taggie. ‘I’ve just lent Daddy a hundred pounds for a new pair of cords for Ireland.’

‘At least I’ll be gone for nearly a week, so you won’t have to feed me,’ cajoled Caitlin. ‘So that’s worth fifty.’

‘And we haven’t done your trunk yet,’ wailed Taggie. ‘You’ve grown out of everything, you need new Aertex shirts, and both your games’ skirts are split.’

‘Oh, sew them up,’ said Caitlin airily. ‘We can’t possibly afford new ones if we’re so poor.’

RIVALS

39

After a riotous five days in London, Caitlin rolled up at Paddington Station with just enough money for her half-fare home. Her blue-black hair was coaxed upward at the front into a corkscrew quiff. She was wearing peacock feather earrings, a black and white sleeveless T-shirt, a black Lycra mini which just covered her bottom, laddered black tights, huge black clumpy shoes, all of which belonged to various friends of hers, a great deal of black eye make-up, and messages in Biro all over her arms.

It was hardly surprising, therefore, that the man at the ticket desk refused to believe she was under sixteen. A most unseemly screaming match ensued, which first amused then irritated the growing queue of passengers behind Caitlin, who began to worry they might miss their trains home.

‘My father is a very very famous man,’ screamed Caitlin as a last resort, ‘and he’ll get you.’

‘Don’t threaten me, young lady,’ said the booking clerk.

‘It’s people like you who turn liberals like me into racists,’ screamed Caitlin even louder. ‘You’re just discriminating against me because I’m white. I’ll report you to the Race Relations Board.’

At that moment Archie Baddingham, on his way home from his three weeks’ banishment in Tuscany, reached the top of the neighbouring first-class queue. Hearing the din, and recognizing Caitlin’s shrill Irish accent from New Year’s Eve, he bought her a ticket.

‘Remember me?’ he said, tapping her on the shoulder.

‘No, yes,’ said Caitlin. ‘You’re Archie, aren’t you? Can you lend me my fare, this stupid asshole won’t believe I’m under sixteen.’

‘I’ve got you a ticket,’ said Archie.

‘I can’t accept a ticket from you,’ stormed Caitlin irrationally. ‘Your father’s been absolutely shitty to my father.’

‘My father’s shitty to everyone,’ said Archie, calmly taking her arm. ‘Come on, we’d better move it.’

They only just caught the train on time, but managed to find two single seats opposite each other.

‘I’ve never travelled first class,’ said Caitlin, stretching out on the orange seat and squirming her neck luxuriously against the headrest.

Archie looked wonderful, she thought. Like her, he’d shot up and lost weight. He was wearing black 501s, rolled up above black socks and black brogues with a black polo-neck tucked into a western belt with a silver buckle, black crosses in his ears, and a brown suede jacket. His blond hair, washed with soap to remove any shine, was long at the front and cut short at the back and sides. His still slightly rounded face looked thinner because of a suntan almost as dark as his eyes.

‘Why are you so disgustingly brown?’ asked Caitlin.

‘I’ve just spent three weeks in Tuscany. My parents booted me out there to get over a girl.’

‘Tracey-on-the-Makepiece.’

Archie grinned, making him look even more attractive. ‘How d’you know that?’

‘You were superglued to her at Patrick’s twenty-first.’

‘So I was. Actually, I’m over her, but Dad and Mum thought I wasn’t, so I thought I might as well take advantage of a free holiday. Have you been away?’

‘We never go anywhere. My parents are always broke. No, it’s quite OK. Nothing to do with your father. They’re just hopeless with money.’ There was a pause. Caitlin gazed out of the window, wondering what to say next.

‘What would you like to drink?’ asked Archie.

‘They got any Malibu?’

‘I doubt it.’

‘Well, vodka and tonic, then. Can I come with you?’

The Inter-City, belting towards Bristol, swayed like a drunk as they walked towards the buffet car.

‘Have you had any lunch?’ asked Archie, admiring her narrow waist and slim legs which were more ladder than tights.

‘No,’ said Caitlin.

‘I’ll buy you some grub then,’ said Ar

chie.

‘Been to a funeral?’ said the gay barman, running a lascivious eye over Archie’s black clothes.

‘Passengers are reminded that it is an offence to serve intoxicating liquor to persons under the age of eighteen,’ read Caitlin loudly, as Archie paid for everything.

‘Keep your vice down,’ hissed Archie.

The journey back to their seat, with each of them carrying white plastic trays of vodkas and tonics, glasses, bacon sandwiches, Mars bars, and packets of crisps, was much more hazardous. They had no hands to steady themselves against the lurching train.

‘Terribly sorry,’ mumbled Caitlin, going scarlet, as for the third time she cannoned off a commuter back into Archie.

‘Who’s complaining?’ said Archie.

‘Thank you so much,’ said Caitlin as they sped past slow winding rivers, rolling fields, and clumps of yellowing trees. ‘This bacon sandwich is the best thing I’ve ever tasted.’

‘I’m surprised you can say that with Taggie cooking for you,’ said Archie. ‘Every time my father compliments my mother on the food, it turns out Taggie’s made it. How is she?’

‘Bit low. She’s hopelessly hooked on Rupert Campbell-Black.’

‘Won’t do her any good,’ said Archie, pouring out a second vodka and tonic for Caitlin. ‘He strikes women down like lightning bolts. Anyway, he’s bonking my father’s ex.’

‘Cameron Cook,’ said Caitlin dismissively. ‘She’s a crosspatch, isn’t she? I can’t see what men see in her. My brother was crazy about her, and now she’s gone off to make a film in Ireland with Daddy. I hope they don’t end up in bed. People usually do on location, don’t they? I’d loathe her as a stepmother.’

‘Dad was mad about her. I was shit-scared he’d leave Mum and marry her,’ said Archie, breaking a Mars bar and giving half to Caitlin. ‘I dread my parents getting a divorce, in case they marry again and leave all their money to their new children.’

Caitlin giggled. ‘Mine haven’t any to leave.’

‘I hear your mother’s joined the cast of The Merry Widow. Mum told me on the telephone that she’s streets ahead of everyone else.’